As early as 2012, the announcement of a 'shale gas' exploration project conducted by Shell led to controversy. A contract providing for the drilling of nearly 742 wells in the Kairouan region, as well as the use of the "non-conventional" technique of hydraulic also known as "fracking".

"Fracking" poses a risk of polluting the groundwater due to the practice of injecting high-pressure water mixed with various toxic additives in order to break up deep rocks that are rich in hydrocarbons. In France, this practice has been banned since 2014.

In addition to the known short-term profitability of this type of well, a big concern is the excessive consumption of water. This is a serious threat for Tunisia, which is one of the 33 countries facing major water shortages by 2040, according to the World Resources Institute. However, this does not prevent large companies, notably Perenco (Europe's largest oil and gas company), from carrying out extraction activities that are dangerous for the water resources and the environment.

A suspicious satellite image

In 2015, the Shell project was finally abandoned in Kairouan. However, the same year, the Heinrich-Böll Foundation published a report entitled "Gaz de schiste en Tunisie: entre mythes et réalités" [Shale gas in Tunisia: between myths and realities]. This time, it was the 'Perenco' company that was singled out. A satellite image that was published in this document, shows a well, surrounded by several water reservoirs. Operated by the Franco-British company, this well is located in an area corresponding to shale reserves. However, Perenco claims that it only exploits so-called "conventional" reserves.

All of these factors seem to indicate a hydraulic fracturing operation. This hypothesis is corroborated by a company press release published in 2010, which Perenco eventually denied and removed from its website.

Despite these images, both Perenco and ETAP (Tunisian National Oil Company) claim that no unconventional activities have ever been carried out. "Tunisia has never extracted shale gas", the latter asserted in 2013. This public agency is the manager and co-owner (together with Perenco), of the El Franig site.

Satellite image of the El Franig concession operated by Perenco, produced by the Heinrich-Böll Foundation on December 12, 2012. Google Earth.

Compact gas,

a

"non-conventional" resource

Despite these statements, it has been possible to establish the existence of at least eight episodes of hydraulic fracturing at the majority of the wells located at the El Franig site, and to determine their depth. Indeed, the extraction of non-conventional resources requires drilling deep underground: more than 3,000 metres, on all sites.

The reservoir (a geological layer containing pockets of hydrocarbons to be extracted) of the El Hamra concession is a so-called "compact" reservoir: it is thus trapped in a layer of quartz located only a few hundred metres from the bedrock, where part of the shale reserves are stored.

Even though no international convention has defined these categories to date, the current consensus is that compact reservoirs are considered as "non-conventional" reserves, in the same way as bedrocks containing gas, oil and shale oil. This is for example the case in France and the rest of the European Union. In the United States, the use of hydraulic fracturing alone is sufficient to use this term. Both of these definitions are relevant to Perenco's activities.

In Tunisia, despite the absence of an official definition, a document presented by the Ministry of Industry in 2013 provides an interpretation in line with Western definitions. It explains that "non-conventional" is the "process of extracting hydrocarbons".

According to this definition, the fracturing techniques used at the El Franig site, as well as the Baguel-Tarfa fields, correspond to non-conventional methods.

Indeed, at El Franig, beyond the fracturing technique used, all the wells produce from a non-conventional reservoir, without exception. In addition to this, Perenco did develop an "experimental shale well" and carried out extensive hydraulic fracturing in 2010 on the EFR-5 well located on the same site. This information is set out in black and white in an amendment to the concession contract that was signed in 2012, which called for the shutdown and "disgorgement" of the latter.

The El Franig extraction site © Alexandre Brutelle

Insufficient regulations

The Tunisian hydrocarbon code does not provide any legal framework for managing this type of energy resource. For Afef Hammami-Marrakchi, lecturer at the University of Law in Sfax, the very nature of Perenco's activities is problematic from a legislative point of view.

Thus, she explains that the use of environmentally damaging extractive techniques is supposed to be subject to parliamentary debate, whether for shale gas or for any other non-conventional resource (including compact reservoirs), according to Article 13 of the Tunisian Constitution.

However, ETAP does not deny the non-conventional and illegal nature of their current operations. "These concessions are governed by the laws of the old legal regimes, instituted before the Hydrocarbons Code of 1999 came into force and the new Constitution of 2014 was adopted", the agency states.

According to the previously mentioned amendment, the concession was indeed created in the 1980s. An application for renewal was approved in 2011 by the Hydrocarbons Advisory Committee, and the agreement was signed in April 2012, barely two years before the adoption of the Constitution.

Moreover, the exploitation of these areas has been the subject of several heated debates in the National Assembly. In 2014, the Energy Committee rejected the renewal of the El Franig and Baguel permits.

The company had been singled out for "numerous breaches of operational rules", allegedly benefiting Perenco, to the detriment of the state.

The issue then resurfaced in 2016, and divided the MPs once more. In both cases, the permits were ultimately renewed.

Finally, the classification of oil and gas sites as military zones in 2017 reinforced the obscurity surrounding these sites. On the one hand, it ensures the continuity of operations of foreign companies on Tunisian soil, whilst alos making these concessions off-limits to the general public. Thus, in April 2021, the author of this investigation was arrested twice by the army when reporting, for having taken pictures on roads outside the military zones.

Photo of a Tunisian production site published in a Perenco Group sales brochure.

In addition to the lack of regulations, there is a certain obscurity surrounding Perenco itself. During the course of the investigation, it was established that five of Perenco's six Tunisian subsidiaries are registered outside of Tunisia. Four of them are registered in notorious tax havens such as the Bahamas or the State of Delaware in the US. The amendment to the Baguel-Tarfa concession contract mentions Perenco Tunisia's head office as being registered in the Cayman Islands, a common practice among oil companies operating in Tunisia. In the framework of the Pandora Papers, inkyfada investigated the oil business of Ahmed Bouchamaoui, one of the subsidiaries of which is registered in the British Virgin Islands.

On the same subject

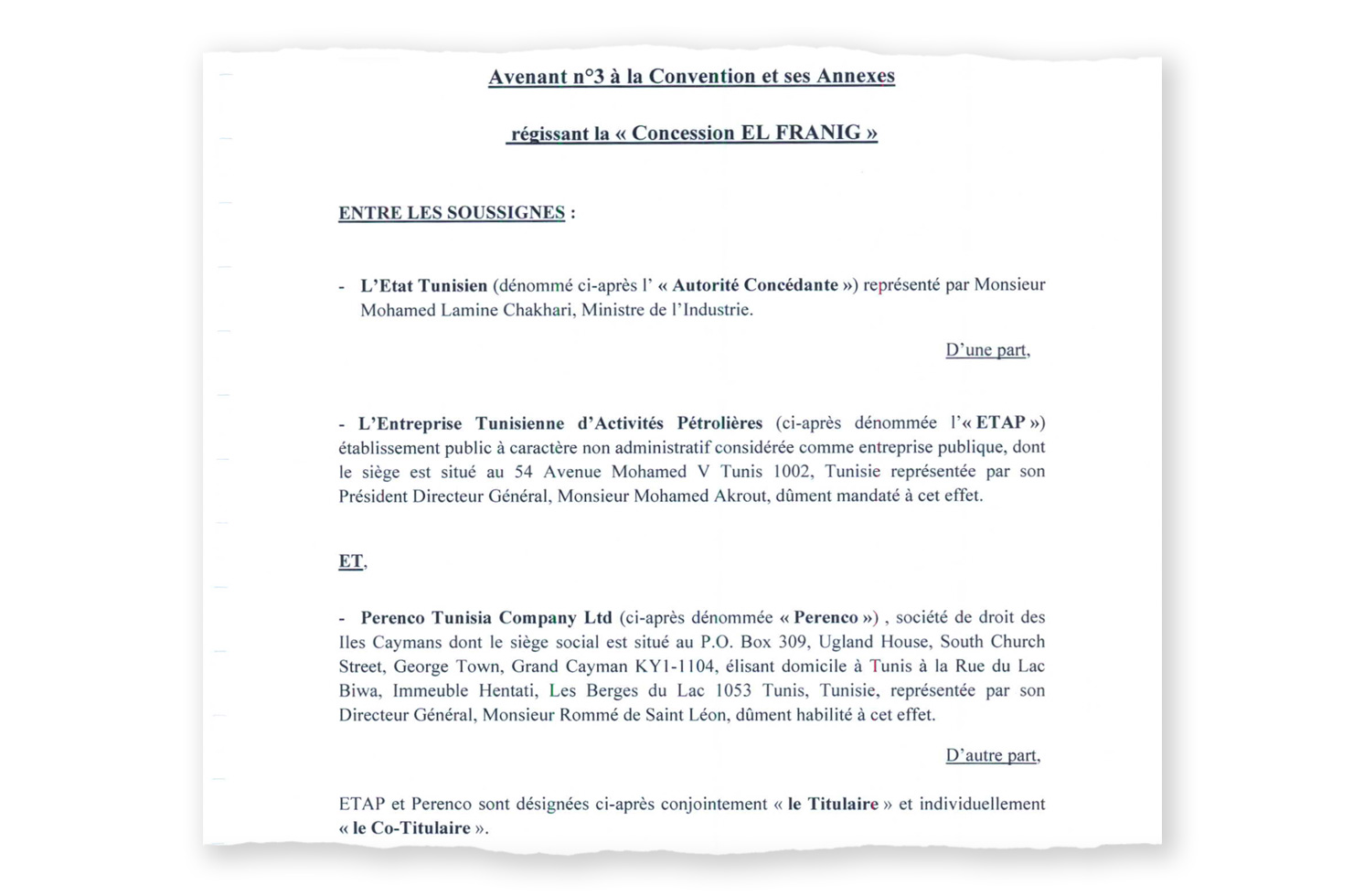

Amendment #3 of the Franig concession, Tunisian National Oil Company (ETAP), April 2012

An ecological heritage

on the front line

Within a 15 square kilometre operational radius, the El Franig concession is encircled by the village of El Farouar, nearly 80 palm groves and oases, and 49 surface water points where local livestock and wildlife drink. Perenco's operations pose a potential danger to both local flora and fauna if the drinking water becomes contaminated with groundwater.

Interactive map of the extractive activities of Perenco El Franig, Kebili, Tunisia. 'Remote Sensing Limited' for the NGO Environmental Investigative Forum (EIF), August 2021.

Tests were carried out on agricultural water collected around the site, as well as on the drinking water in El Farouar.

According to Sabria Barka, ecotoxicologist and co-author of the above mentioned report by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, analyses show that these waters contain several toxic elements in abnormal concentrations, such as lithium, strontium and boron.

This constitutes "a proven environmental and health risk that local populations and authorities should be warned about", the scientist says, even if the direct link with the surrounding oil and gas operations is not clearly established.

On the same subject

It should also be noted that the boundaries of El Franig additionally encroach on the salt lake of Chott El Jerid - a place classified as a wetland of international importance by the Ramsar Convention, an area of great importance for the conservation of birds, and a candidate for UNESCO's World Heritage List. The only impact studies available are in the hands of the Tunisian National Agency for the Protection of the Environment (ANPE), and were produced by the Perenco company itself. Neither the agency nor the company responded to our requests to consult these studies.

El Franig is not the only Perenco gas extraction site operating near environmental assets. The "Baguel-Tarfa" concession, located about 50km from Douz, even encroaches on the boundaries of the Jebil National Park, where several episodes of fracking are said to have taken place in 2014 and 2018, according to several anonymous testimonies received by ETAP employees.

Interactive map of the extractive activities of Perenco in Baguel-Tarfa, Kebili, Tunisia. 'Remote Sensing Limited' for the NGO Environmental Investigative Forum (EIF), August 2021.

This is just a few steps away from a park that is deemed to be the natural habitat of more than a hundred animal species, seven of which are listed by the United Nations' International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as endangered. Three of these species live in the vicinity of Perenco's operations: the critically endangered White Antelope, the Houbara Bustard and the Dorcas Gazelle, which are considered as vulnerable species.

A Perenco valve in Jebil, at the start of the eponymous national park. © Alexandre Brutelle

The Perenco group did not wish to respond to any of the fiscal, legal or environmental issues raised in the investigation. This is not the first time that Perenco has been criticised for its Tunisian operations. In 2018, the organisations ASF and IWatch led an action with the OECD demanding increased transparency on Perenco's activities in Kebili, and calling on the group to respect the standards of conduct required of companies.

Perenco was also confronted in 2021 by a coalition of NGOs denouncing their "organised opacity". A letter was sent to the president of Perenco in France, demanding, amongst other things, increased transparency on their operations in Gabon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Peru, and in Tunisia.