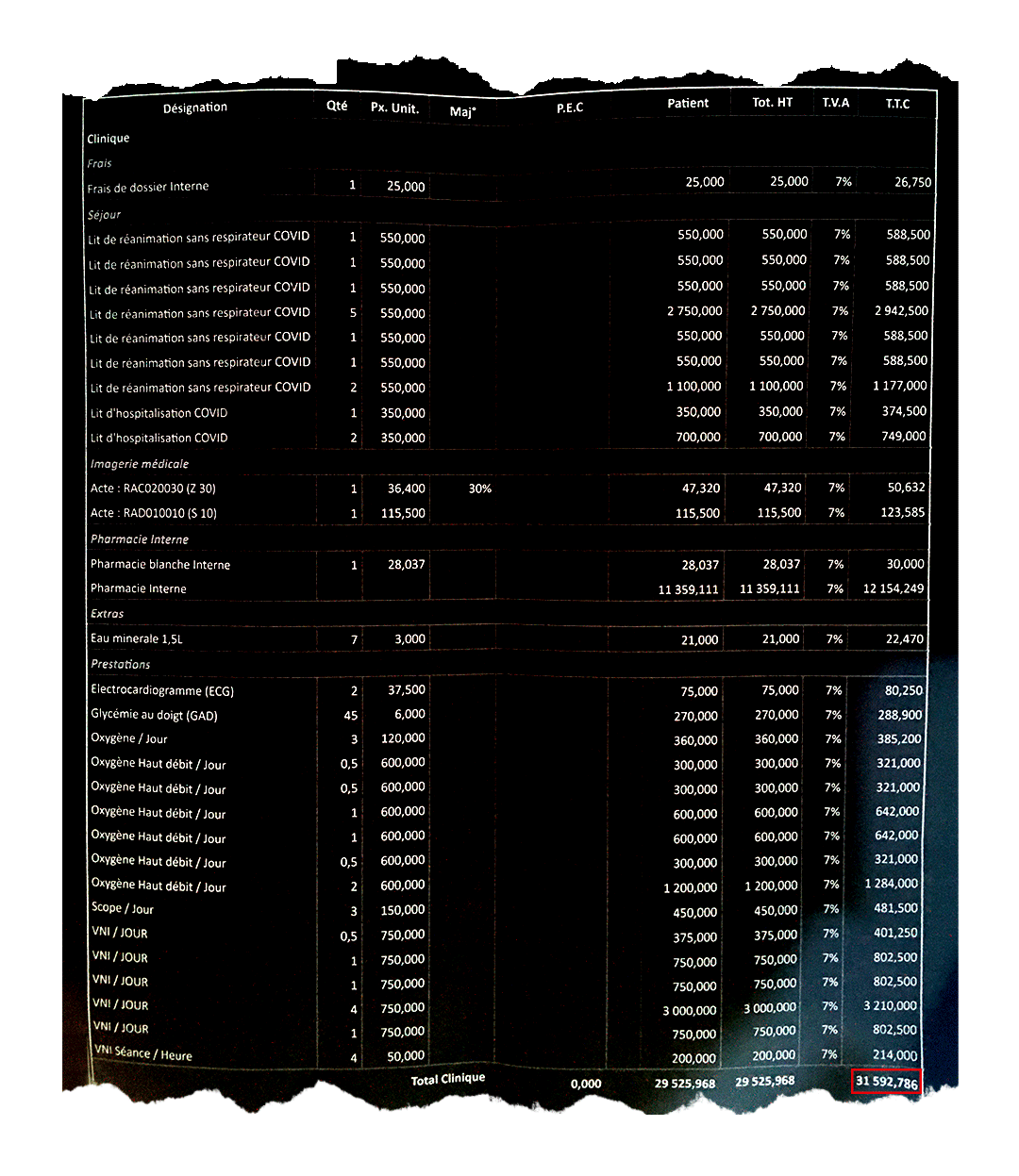

Fadhila is hardly an isolated case. Adam* was also astounded when he discovered the amount for his father’s hospital bill, who died from Covid-19 at the beginning of November. In total: 48,000 dinars for 13 days at the clinic. Every day he received a preliminary invoice, each time more expensive than the last: " I was blown away! In 24 hours, the bill had doubled", he says.

EVERYTHING AT THE EXPENSE OF THE PATIENT

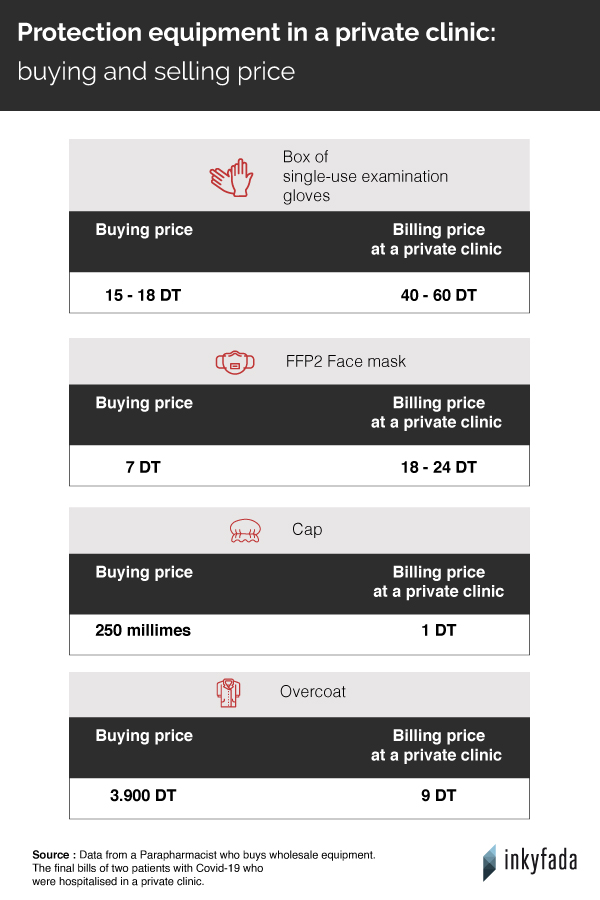

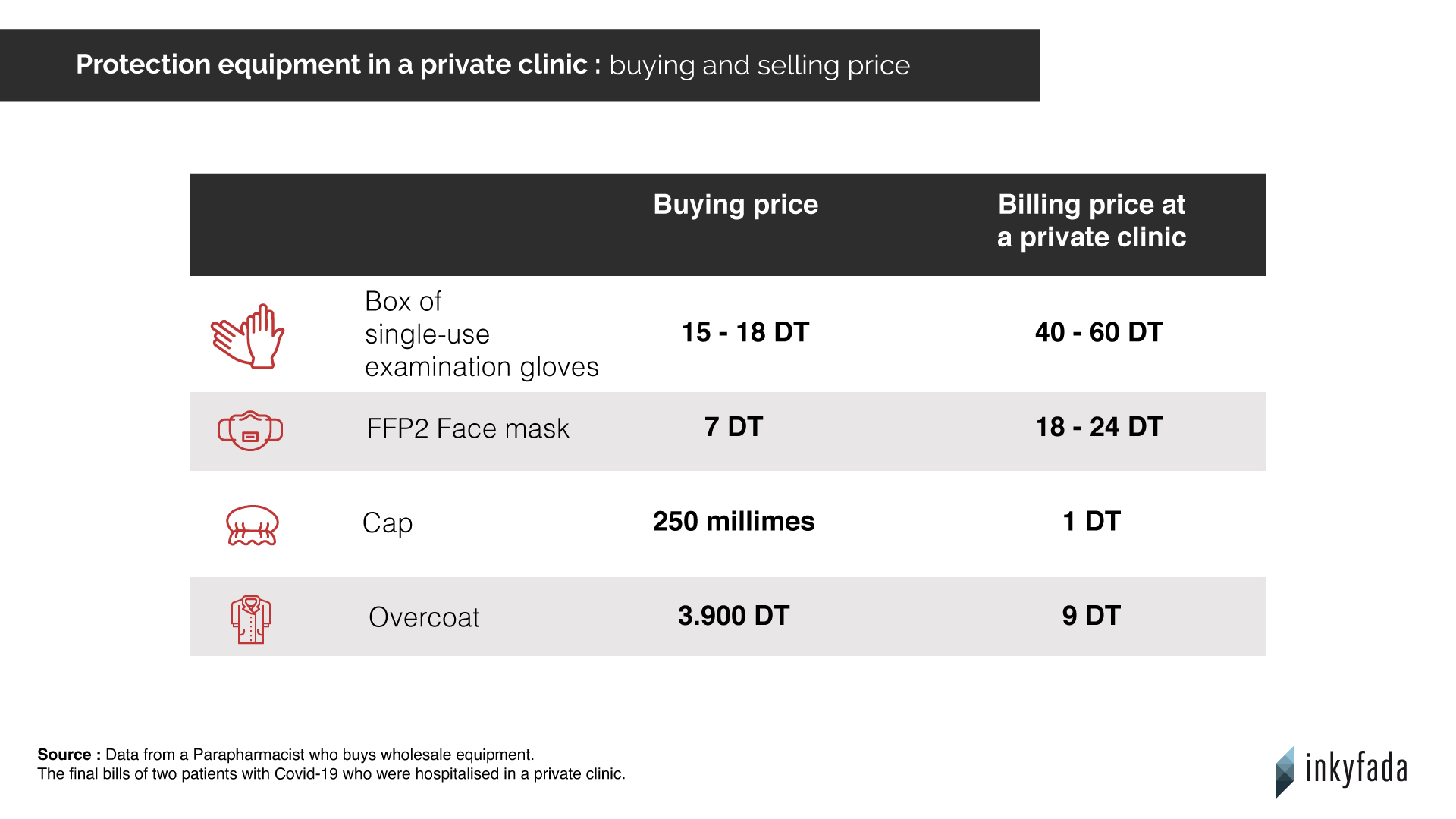

Behind this exorbitant bill, Adam had to pay more than 9,000 dinars of pharmacy fees and 10,000 dinars of medical procedures. From gloves to drugs and doctors' fees, everything is at the expense of the patient. Hedia* who was admitted for 10 days and put on oxygen in a private clinic, was charged more than 3000 dinars for protective equipment, including gloves and even FFP2 masks.

Belkiss* is a para-pharmacist, she regularly buys medical equipment in bulk and has a good knowledge of market prices. She condemns the excessive mark-ups on these products in some clinics: " It’s an insane price inflation", she says. An emergency room doctor at a hospital in Greater Tunis confirms that the quantity of overcoats in Hedia's bill seems excessive to him: " 40-50 overcoats should have been enough."

According to Karim Chayata, president of the Tunisian Right to Health Association (ATDS), private clinics are likely to make significant profit margins, even on accommodation costs: " The price for the room, food, etc., can easily be abused", he explains. On Hedia's bill, a bottle of water cost 3 dinars.

Invoice for an inpatient in intensive care for 14 days. The total amount exceeds 30,000 dinars.

A LACK OF TRANSPARENCY

A few days after his father's death, Adam went to the clinic to settle the last of the fees. He was handed the final bill at the desk, but some details were missing: " I had to go back several times to get additional specifics. It was only during my last visit that I was finally able to get the exact bill", he protests.

As for Hedia and Fethi, the clinic did not provide them with any preliminary invoices. It was only when he came to pick up his wife that Fethi discovered, stunned, the amount to be paid: " On the last day we were sent the final bill and the doctors' fees. Despite our requests, the clinic refused to grant us instalment payments", he says. The couple therefore had to pay more than 19,000 dinars all at once, without prior notice. " The problem is that we are faced with a clear fact, there is a lack of transparency", comments Emna El Hammi, a health strategy consultant who speaks from her own experience in a private clinic.

Moreover, Adam reports that he was harassed by the clinic staff to pay as soon as possible: " From the moment they got my phone number, the cashier's department didn't stop calling me". Traumatized, he says that this harassment continued until the death of his father.

" My father's body had not yet gone down to the morgue, and the general supervisor was already asking me if I had finished paying all the bills. They’re a real money machine!"

In addition to the stress caused by the disease, there is the anxiety of possibly not being able to receive medical care due to lack of funds. " My father was nervous and shocked by the fact that he had to pay so much money, fully aware that he didn't have it in his account", says Adam.

Patients and their families must then make the necessary arrangements to pay these amounts, with some having no choice but to go into debt. " When we arrived at the clinic, we didn't even have 2,000 dinars in our accounts. We had to borrow money", says Fethi. " My friends wrote me checks that were cashed directly by the clinic.”

THE OVERCROWDED PUBLIC HOSPITALS

Several families attempted to go to public hospitals before turning to private clinics. Samia* recalls the ordeal of her brother who died from Covid-19 in November: " We wanted to take him to the hospital in Jendouba, where he lived. We were shocked by the lack of resources at the hospital, which was already overcrowded. There was only one doctor, and she had no equipment. She took care of everyone! We ended up calling a fully equipped ambulance and headed to a private clinic in Tunis." The Jendouba hospital only has 69 beds that are fitted with oxygen, and no beds in intensive care, according to the data obtained by Inkyfada.

On the same subject

Fethi and Hedia had to deal with the overcrowded public facilities as well. " My wife got sick with Covid-19, and one evening her condition deteriorated, she was having a hard time breathing, we panicked", says Fethi. Leaving the house in the middle of the night, the couple searched the hospitals of Tunis, hoping to find a bed fitted with oxygen - but to no avail.

However, according to data obtained by Inkyfada, the country has 1624 beds fitted with oxygen. As of December 5th, only 1,125 patients had needed to be admitted with respiratory assistance. Unlike the intensive care units, which have been operating under strain for several weeks, the beds fitted with oxygen are officially not at full capacity.

" We went knocking at the doors of the Rabta hospital and the Abderrahman Mami hospital, but were refused: they had no beds available for Covid-19 patients. I was told to go home and use an oxygen concentrator by myself", says Hedia, still in shock.

" I was on the verge of dying, my only choice was to go to a private clinic", she painfully recalls.

Theoretically, an official document should have been given to him by the overcrowded hospitals, allowing him to be admitted to a private clinic, free of charge. On October 18th, the Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi announced that " patients of Covid-19 who cannot find a place in a hospital will be treated in a private clinic at the government's expense".

Nearly two months after this announcement, none of the testimonies collected by Inkyfada can confirm the existence of any such support. Mohamed Chafik Smida, Director General of the St. Augustine Clinic, also confirms that none of the patients transferred from a public hospital to his facility were covered by the government. Contacted by Inkyfada on numerous occasions, the Ministry of Health has not responded to any interview requests.

In Tunis, as in the rest of the country, hospitals are close to reaching their full capacity, and intensive care beds are limited. " Our services are saturated, we have many patients that are put on the waiting list because we can't admit them right away. In intensive care, there is never an empty bed and if a patient is discharged or dies, another immediately takes his place. It's disaster management", says Sami*, an intensive care anaesthesia specialist at a hospital in Greater Tunis, which has about 15 intensive care beds.

During the second wave, when deaths were counted by the dozens every day, the outcome was bitter: " No one was prepared for this second wave, and these days we are short on everything, especially on staff”, Sami adds. Plus, if a certain number of patients find themselves forced to go to clinics because of a lack of spaces in public institutions, it is because " little has been done since March to relieve congestion in the hospitals, except for the arrival of a few more oxygenators", laments Karim Chayata of the ATDS.

A TWO-TIER HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

" We have a big problem in Tunisia, there is no unified healthcare system. The public and private sectors are not complementary to each other, they are parallel worlds", Karim Chayata remarks. His views are confirmed by the report of the Tunisian Association for the Defense of the Right to Health (ATDDS) which highlights the disparities between the public and private sectors. " Healthcare patrons of the public sector, who make up about three-quarters of the population, face serious difficulties in benefiting from adequate quality of services(...) and are sometimes forced to resort to paid services in the private sector", de facto involving healthcare access that directly depends upon financial means.

Private clinics sign collective agreements with the health authorities to set rates that are aligned with those of public hospitals for all medical procedures. But according to Karim Chayata, they " unfortunately rarely respect this price cap", and as far as he is concerned, the methods to ensure the correct implementation of these rates are insufficient.

Non-medical procedures are subject to the free market. " It is the law of supply and demand. Nothing prevents private clinics from making large profits on masks, for example. It is a free-market product, hence the skyrocketing of prices since the beginning of the health crisis.” “ The patients are care seekers, and when they come to ask for care, they have to pay the fees”, justifies Boubaker Zakhama, President of the Union Chamber of Private Clinics.

" I have been observing a boom in the private sector since 2008", Karim Chayata continues. " It's a whole market that has grown to the benefit of clinics" in a relatively deregulated environment. Again, according to the ATDDS report, private facilities " more often than not [follow] the market law without any regulation other than the compliance with a specifications chart", leading to " inconsistencies and disparities that are detrimental to a properly functioning healthcare system".

For Mohamed Chafik Smida, director of the St. Augustine Clinic, " it is unfair that the government takes care of patients within the public sector, without paying for those who end up in a private clinic [as well]". But with an already faltering public sector, Karim Chayata doubts that the government is ready to invest in the clinics: “ We first need to begin with the public sector, which is suffering enormously. The only solution is requisitioning private clinics if the capacity of hospitals is superseded, as in times of war."