As evidenced by these cases, there are various ways to open up bank accounts by using offshore companies; each method offers a different level of shielding from public scrutiny.

For example, Mzoughi Mzabi created a company in which he was the rightful owner, giving him exclusive signing rights for their Swiss bank account and the power to control company management.

Ahmed and Abdelmajid Bouchamaoui chose another route. By establishing proxy leadership within their company, they were able to manage the company without being directors. In both cases, however, their identities were protected; their names do not appear in official company documents.

Raouf Bouchamaoui and his associate, Ali Ben Mbarek, did not use proxies to open up a bank account in Dubai, and although an offshore company was involved in the process, their paperwork does not show up in Mossack Fonseca’s archives.

Mzoughi Mzabi – authorized signatory for a Swiss bank account

A bank account is created in Geneva, Switzerland by an offshore company registered in the British Virgin Islands. The company is controlled by proxy leadership sourced from intermediary companies, and it is owned by anonymous shareholders with unregistered ‘bearer shares.’ In this puzzle of intermediaries and proxies, it was difficult to track down Mzoughi Mzabi as the rightful owner of this company.

The investigation begins with Satra Company Limited, created in April 1989 by Mossack Fonseca via its ‘nominee company,’ at the request of a Geneva-based client.

The Panamanian firm provides dummy directors sourced from its own employee pool for the company. These dummy directors often lend their names to dozens of offshore companies at a time. Their sole task as director is to follow the orders of the rightful owners and sign in their place.

A few days after its registration, Satra Company Limited issues two ‘bearer’ certificates of 5,000 shares each. This type of certificate maintains the anonymity of the shareholders.

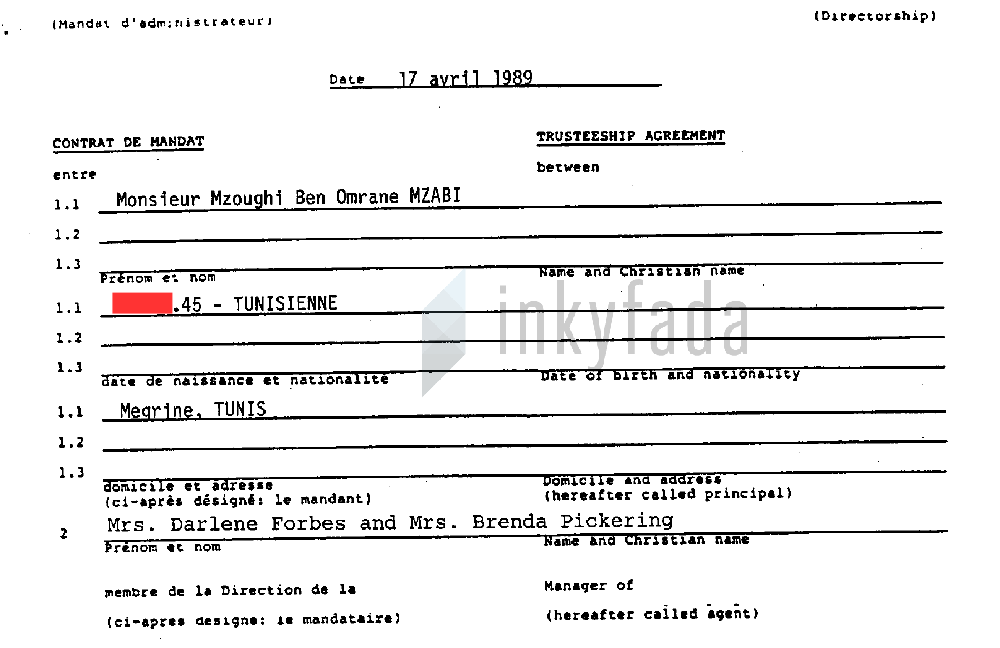

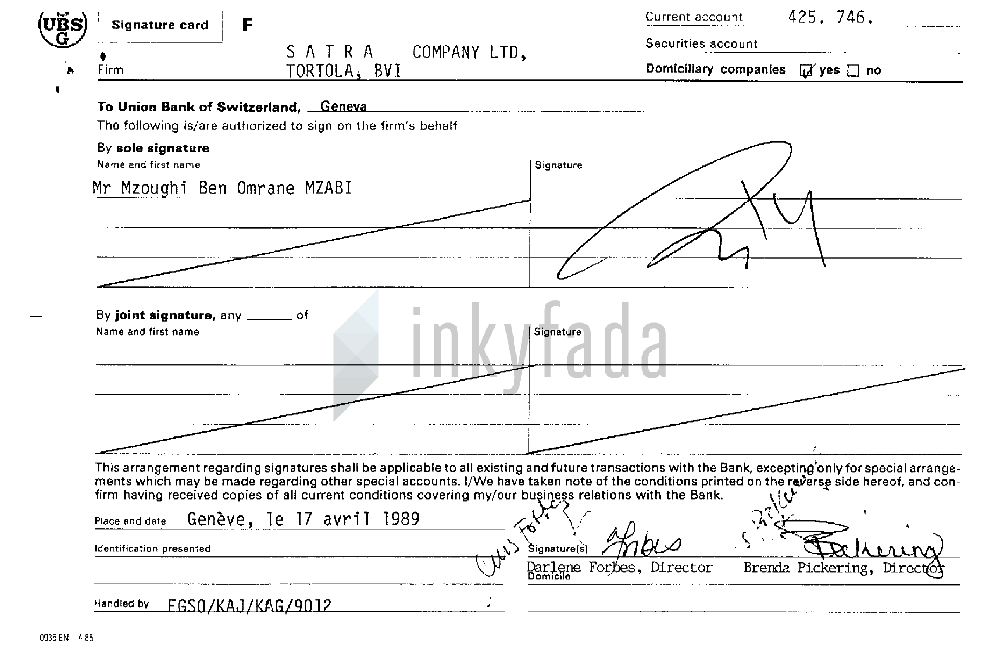

At the same time, Mossack Fonseca produces a power of attorney contract for the opening of a bank account through the Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS). It is in this contract that Mzoughi Mzabi’s name appears. As the “principal officer” of the company, Mzabi agrees to “control the company himself” while nominating two proxy directors to manage it. For the bank account, Mzabi is noted as the only signing officer.

Power of attorney contract for the opening of a bank account with the UBS

Just a few months later, Mzoughi Mzabi would be able to take full advantage of his offshore bank account without his name appearing on any official documents, thanks to an offshore company registered in the British Virgin Islands. This was a service offered by Mossack Fonseca for just a few hundred dollars a year.

In 1998, the Geneva-based intermediary Satra Company Ltd. requests that Mossack Fonseca fill out documents related to the opening of a bank account and sign a number of authorisations for UBS (general authorization for fiduciary investments, pledge, etc.) on behalf of the company’s directors. The company was dissolved a year later in August 1999.

Mzoughi Mzabi signs to open an account with the UBS

A few years down the line, we find that Moncef Mzabi followed in his brother’s footsteps, but evidently with less precaution. According to the Tunisian listings of Swiss Leaks, disseminated by Inkyfada in 2015, Moncef Mzabi opened up a bank account with HSBC Private Bank in 2004.

Despite the account registered in his own name, Mzoughi Mzabi denied the link in his first interview with Inkyfada on May 6th. “ I do not have a company . . . This is not me, you are wrong,” he said. “ If you have a bank account in my name, give it to me so that I may get the money,” he joked.

A few hours later, Mzabi called Inkyfada back: “ What do you want? Where do you want to go with this?” Annoyed, he said that he “ employs two thousand people in Tunisia,” and deplored the fact that they want to “ soil the reputation of someone who employs a lot of people.” “ You, you could understand, but the average person that earns 500 dinars per month, what will they think?” he added without further comment.

The Bouchamaouis' proxies

According to Mossack Fonseca’s leaked documents, Ahmed Bouchamaoui and his late father, Abdelmajid, attained general power of attorney for a company by the name of Inersa Investments INC., which was created in the British Virgin Islands in August 1995.

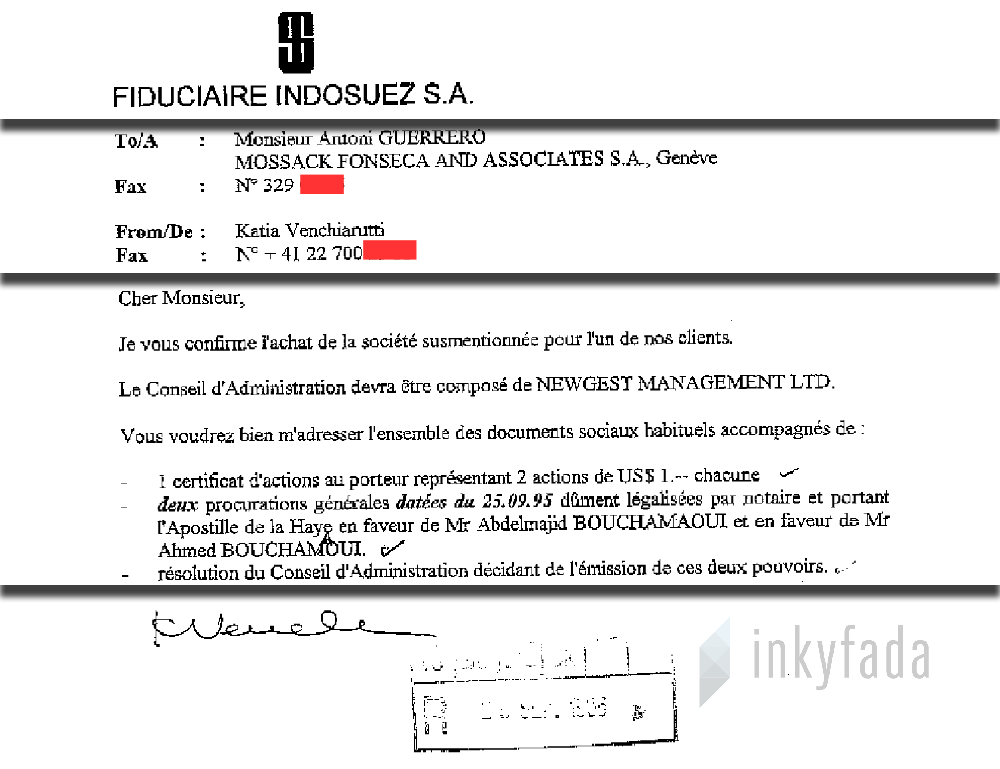

The company was created with a starting capital of 50,000 USD at the request of Fiduciaire Indosuez S.A., a Swiss subsidiary of Crédit Agricole (playing the role of an intermediary). The company was set up via Mossack Fonseca’s Geneva office.

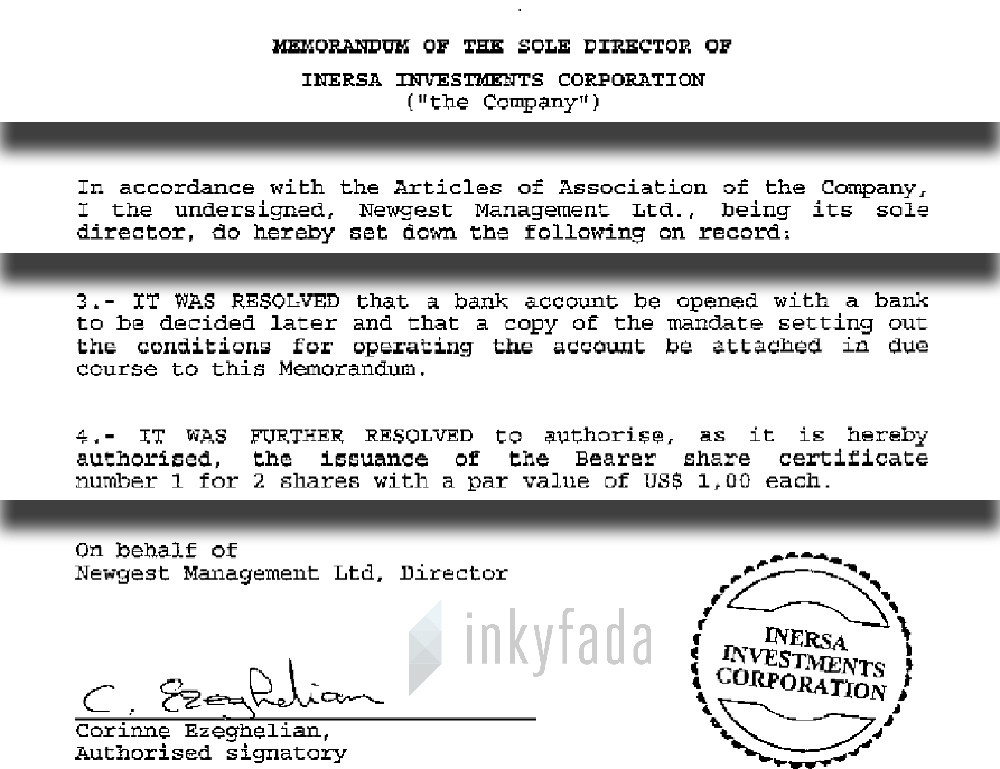

On September 21st, 1995, the management of the Board of Directors was entrusted to a management firm by the name of Newges Management Ltd. Three days later, this intermediary informed Mossack Fonseca that Inersa Investments was sold to an unspecified client and requested that the firm issue two bearer share certificates as well as two general power of attorneys for Abdelmajid and Ahmed Bouchamaoui.

The management firm also shared its intention to create a bank account, through proxy ownership, at an unspecified institution.

With the power of attorney, the Bouchamaouis enjoyed the same powers as the appointed directors of the company, including the opening of bank accounts, without having their names appear on official company documents.

But these powers would be revoked on June 29th, 2004. The documents from Mossack Fonseca disclose neither the dissolution of Inersa Investments nor the identity of the final beneficiary for whom Newges Management would continue to work. Ahmed Bouchamaoui was not reachable when Inkyfada tried to contact him on several occasions.

Raouf Bouchamaoui, from Dubai to the Seychelles

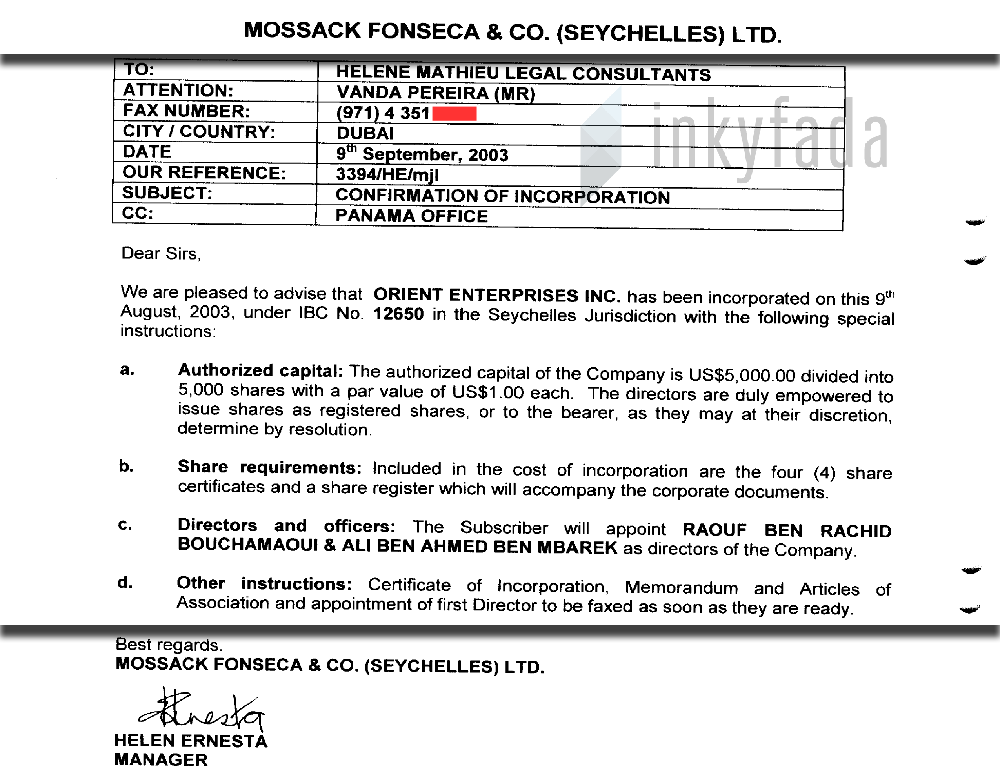

Raouf Bouchamaoui, a cousin of Ahmed Bouchamaoui, also features in the leaked documents. He was identified as a director of Orient Enterprises INC., along with Ali Ben Mbarek, a businessman and member of UTICA. Orient Enterprises was created in the Seychelles on August 9th, 2003 by Mossack Fonseca, with the help of an advisory firm in Dubai.

“ I know Ali Mbarek. He used to work in Iraq. But I do not remember opening up a company with him . . . I have no idea about it,” Raouf Bouchamaoui told Inkyfada during an interview on May 5th, 2017. “ I may have discussed with him the possibility that we conduct business together but I do not remember that our discussions led to anything, I really do not remember,” he insisted.

As is typical for these kinds of entities, the starting capital of Orient Enterprises was very low (5,000 USD) and the directors enjoyed many exclusive rights (they could distribute nominative or bearer shares, dismiss directors, etc.). According to the documents leaked from Mossack Fonseca, this company was never dissolved.

Raouf Bouchamaoui and Ali Ben Mbarek appointed as co-directors of Orient Enterprises Inc

Even if “ companies registered in tax havens have a bad reputation . . . it doesn’t mean anything” said Raouf Bouchamaoui. “ The Bouchamaouis have been conducting business [in Tunisia] for 50 years and internationally for 70 years. Our group employed 7,000 people in Libya,” he said.

“ If we used these kinds of companies, they would still be liable to pay the stipulated taxes to the countries in which they are active. Well, there are cases where companies are used to hide commissions, but this is not the case for us. We are entrepreneurs and we have real activities,” he said.

“ Sometimes we have to go abroad for reasons of operational optimization or to get bank guarantees,” he said, reiterating that he did not remember the company created by Mossack Fonseca.

A few days later, the two men finally remembered the company Orient Enterprises INC. According to Ben Mbarek, they had created the company through their consulting firm based in Dubai, where they were both residing at the time. “ The company was used to respond to calls for bids, in Iraq and Gulf countries, in the food or construction industries.” He went on to say that if a bank account was indeed opened in Dubai for the company, it was never really used. “ We had objectives that we did not reach . . . but I insist on the fact that everything was legal.”

Shaky memories and justifications

“ There is no bank account,” “ I am not a shareholder,” “ the company capital is insignificant,” “ this company was never active:” these were only some of the evasive comments given to Inkyfada during interviews with the Tunisians implicated in the Panama Papers.

Some claimed to have legitimate, legal reasons for opening offshore companies. “ The company was meant to strengthen a non-resident Tunisian trading company that was export orientated. It provided a British name and an address in the West,” Mahmoud Trabelsi responded.

Others “forgot.” Businessman Trabelsi failed to dissolve the company that he co-owned with Noomane Fehri during the 1990s, until finally closing it in November 2011. Raouf Bouchamaoui and Ali Ben Mbarek initially had no recollection of their offshore company.

As for Jamel Dallali, the founder of the Tunisian television chain TNN, he wanted to “ protect the intellectual property of his brand.”

No money, no activity, no identity: this opacity is one of the main characteristics of tax havens, explains Neila Chaâbane, specialist in tax law. An empty shell, a P.O. box, and a certificate can be sufficient to conduct many financial or commercial activities, anywhere in the world. Around these companies gravitate consulting firms and lawyers, banks, managers, and intermediaries. Without ever having to leave their offices, these players come together to skirt around the law.