Stay quiet, it will pass. The publication of the Pandora Papers - the largest journalistic investigation in history, conducted by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (the ICIJ) - has elicited next to no reaction in Tunisia, whether from politicians or the justice system.

However, according to the documents accessed by inkyfada, no less than thirty Tunisians are mentioned as implicated. Among them we find businessmen and women, politicians, as well as unknown persons. Inkyfada investigated 9 of these individuals.

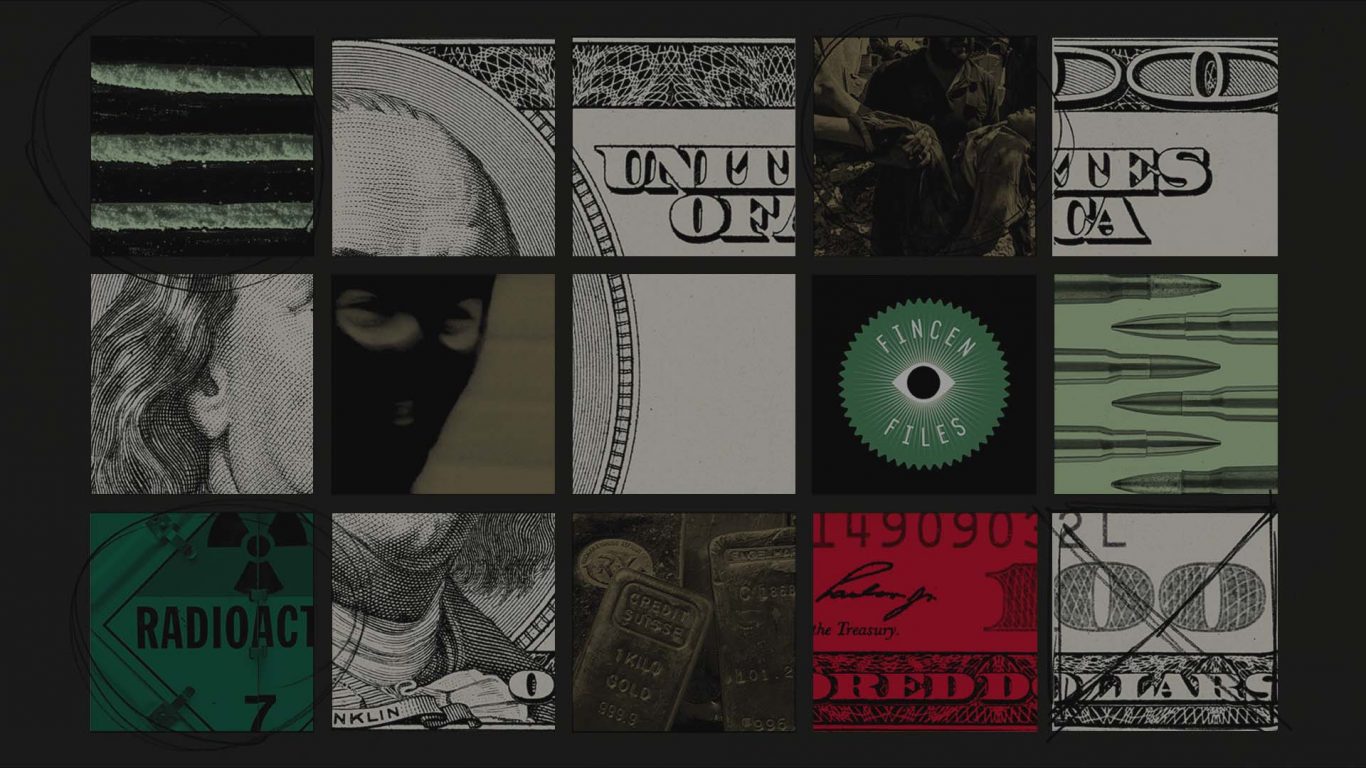

This investigation was far from being the first one of its kind that inkyfada participated in. Before it came the SwissLeaks, the Panama Papers, the Paradise Papers and the FinCEN Files, all with a Tunisian section investigated by inkyfada and various partners. Despite this, the outcome remains the same: the revelations have had virtually no consequences, whether on the political or the judicial side of things.

SwissLeaks: $554 million in Swiss accounts

Since 2015, inkyfada has been collaborating with the ICIJ, based in Washington D.C. That year, the media outlet published the Tunisian section of the SwissLeaks, an affair that began in 2008, when a former HSBC Private Bank computer expert, Hervé Falciani, handed a list of 106,458 clients in 203 countries over to the French authorities. Some of these clients were in compliance with the law, while others were engaging in tax evasion.

According to research by the French authorities, no less than 256 people with links to Tunisia were identified, whether by nationality, birthplace or place of residence. According to ICIJ calculations, no less than 554 million dollars (about 1.6 billion dinars) were held in Swiss accounts between 2006 and 2007.

On the same subject

Following these revelations, legal proceedings were launched by the Tunisian judiciary. A request for mutual assistance was filed with the French justice system, to which it responded favourably by making information concerning Tunisians linked to HSBC available to Tunisia. Despite several unanswered requests for access to information, it has not been possible to verify the progress of these investigations today.

Panama Papers: Investigations and a parliamentary committee

Then in 2016, inkyfada published the section of the Panama Papers relating to Tunisia. A vast document leak exposed 14,153 clients of the Panamanian firm Mossack Fonseca. Just like the firms Alcogal and SFM (which were named in the Pandora Papers), Mossack Fonseca specialises in the creation of financial arrangements via offshore companies.

Yet again, several Tunisian or people with connections to Tunisia were mentioned in the leak. For example, we found the names of politicians Mohsen Marzouk (the former campaign manager of Béji Caïd Essebsi), Noomane Fehri (the former Tunisian Minister of Communication Technologies and Digital Economy), and the businessmen Ahmed, Abdelmajid, Raouf Bouchamaoui and Mzoughi Mzabi.

In response to the worldwide outcry over this matter (which was published by inkyfada and more than 100 media partners), the political authorities reacted, at least on the surface. The then Minister of Justice asked the public prosecutor of the Tunis Court of First Instance to "do what was necessary" with regards to the Tunisians cited.

According to the judge in charge of the case, a judicial investigation was opened in April 2016, with a request for mutual legal assistance from the Panamanian judiciary. This, despite the fact that almost all the companies and bank accounts identified by inkyfada are located in other jurisdictions.

The National Anti-Corruption Commission (INLUCC) also examined the case, but closed the investigation upon the request of the financial judicial division. a According to a representative of the Instance, several people had been questioned. "The majority denied being linked to companies based in tax havens. Other people provided additional documents concerning the companies mentioned", he said.

However, this information was contradicted by Mohsen Marzouk. "None of the other names mentioned in the Panama file have appeared before the courts, and they have not answered to any investigation", he told inkyfada, while specifying that he himself had to go to the judge of the Economic and Financial Pole to be questioned.

Six years after these findings, it is still impossible to verify the progress of the legal proceedings. Inkyfada has submitted several requests for access to information to the Economic and Financial Judicial Pole, as well as the Ministry of Justice to which it belongs, without any response.

On the legislative side, the parliament decided on April 8, 2016, to create a parliamentary investigation committee*. Composed of 22 deputies, its purpose is to investigate corruption and tax evasion, as well as the Tunisian individuals mentioned in the Panama Papers.

On June 4, inkyfada received a request for a hearing from the commission, which they refused, on the grounds that they are "not involved in the work of the commission" (see the full press release). The commission met only once, on June 27, to question the minister of state property, according to the Majles Marsad website. None of its work has been made public.

International tax evasion:

a significant challenge for the Justice system

The publication of the Pandora Papers and the subsequent lack of reaction from the state has once again called into question its inaction in the fight against international tax evasion, particularly that of the judiciary. According to Neila Chaabane (professor of public law at the Faculty of Legal, Political and Social Sciences in Tunis), the complexity of the cases in question and the lack of resources are coupled with the lack of political will to address the situation.

"These investigations take time", she explains. "There are letters of request that have to be launched abroad, you need to have preliminary files to be able to get information from the other side, it's not something straightforward."

"Generally, these states are quite reluctant to respond to such requests", she says.

Another factor is the robust nature of the financial arrangements put in place by the specialised firms. Often the arrangements involve several jurisdictions between the client's place of residence, where the company is established, and where the assets are located. In addition, the use of figureheads makes it possible to ensure the anonymity of these arrangements. "It is really difficult to obtain proof if we limit ourselves to what is available here in Tunisia", says Neila Chaabane.

A lack of transparency

At the same time, the judiciary maintains a complete lack of clarity about the ongoing cases. "I cannot discuss the progress of the investigation because of my confidentiality obligation", explained Judge Sahaba, who was in charge of the Panama Papers investigation for a while.

This information was confirmed by the Dean of the Faculty: "there is confidentiality of investigations for all criminal cases, the trial only becomes public at the time of the verdict", this rule serves to protect the various parties and to guarantee a fair trial. As inkyfada experienced during their investigations, it is extremely complicated to access information.

Inkyfada submitted four requests for access to information in December 2021: two in print to the Ministry of Justice and the Economic and Financial Judicial Pole, and two via email to the Tunisian Financial Analysis Commission (CTAF) and the Central Bank. Email tracking makes it possible to know that the latter two have been received and opened. As the legal deadline for a response was largely exceeded by these institutions, inkyfada considers this as a failure to respond.

On the same subject

A limited legislative progress

"The objective of combating tax evasion and avoidance has always existed, it is not new", Neila Chaabane explains. The fight against international tax evasion is part of the state's fight against domestic tax evasion. In recent years, the country's legislative apparatus has undergone several changes in order to be more effective.

In 2017, the finance law provided for the creation of an Investigation and Anti-Tax Evasion Brigade, part of the tax department. "The officers of the Investigation and Anti-Tax Evasion Brigade proceed to the research of criminal tax offences and the collection of its evidence throughout the Tunisian territory [. . .]", specifies Article 80ter. Its prerogatives are therefore restricted to the national territory.

The same law simplifies "the procedure for lifting bank secrecy" (Article 37), a measure extended by the 2019 Finance Act.

The placement of Tunisia on the European Union's blacklist in December 2018 has accelerated decision-making such as the adoption of the OECD guidelines.

"Determined to act against practises of tax avoidance, Tunisia has chosen to adhere to international initiatives to combat BEPS [erosion of the taxation base and transfer of profits] in order to better protect its taxation base and improve the mobilisation of tax resources necessary for its sustainable development", declared Mohamed Ridha Chalghoum, former Minister of Finance, quoted in an OECD report.

However, other measures show the limits of the country's battle. Mere months after the adoption of these guidelines, the definition of a tax haven was reclassified as a "territory with a privileged tax regime". This new definition only takes into account the amount of taxation in the given territory, which needs to be 50% lower than under Tunisian law.

"Tunisia has thus obstructed all other criteria defining a tax haven", a tax expert comments. For example, Oxfam refers to the lack of transparency: the organisation points out that these countries have laws or administrative practices that prevent the automatic exchange of information. The NGO also highlights the presence of tax advantages that do not require any business activity on the territory.

"This is how countries like Mauritius find themselves excluded from the list, while multinationals rush to this small country to create shell companies with figureheads", the expert continues.

In the absence of any official figures, it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of all the measures adopted over the past few years. In a report by the think-tank 'Solidar Tunisia' from May 2018, the blame is directed at the implementation, or rather lack thereof, of the voted measures. "The non-implementation of these provisions represents considerable losses for the Treasury", the report concludes.

As for the fight against international tax evasion, Neila Chaabane believes that the situation will not evolve as long as the legislation on foreign exchange does not improve. Tax evaders "create offshore and shell companies to escape this regulation which is now obsolete", she explains.

Tunisia, far from an exception

On the same subject

Tunisia is not the only country facing problems with tax evasion. "These are challenges that all states are confronted with. The biggest cases occur in the major economies", comments Neila Chaabane.

On a global scale, tax evasion was estimated at 483 billion dollars in 2021, according to a report by the NGO Tax Justice Network. For a country like France, the total amount of tax evasion corresponded to 3% in 2012, according to a report by the French Senate.

In the fight against tax evasion, all the states concerned are faced with the same difficulties.

"As soon as the spotlight is shone on one country or territory, the money goes elsewhere", explains Neila Chaabane.

Indeed, by cross-referencing data from several investigations, the ICIJ has revealed that more than a hundred companies left Mossack Fonseca to join Alcogal (one of the firms singled out in the Pandora Papers) after the Panama Papers were published, demonstrating a certain degree of impunity.

According to Neila Chaabane, Tunisia is neither worse nor better than any other country in this regard, since the stakes are on a different scale. "It is the system that produces and allows tax havens to develop. If the G7 really wanted to put an end to tax evasion, it would do so."