Faced with this controversial situation, Khaled Marzouki was finally dismissed a few days later. However, this was only the tip of the iceberg, as many other defendants are still at liberty, and the trials are being stalled.

On the same subject

Mimoun Khadraoui knows a thing or two about this. Since the beginning of his brother’s trial in October 2018, who was killed during the events of Kasbah 2 in Tunis, he has not missed a single hearing. "There have been five hearings and each time nothing happens, the hearing is postponed because the defendants do not show up. There is nothing new", laments Mimoun Khadhraoui.

"It is not normal that three years after a transfer, no verdict is reached. It's a virtual denial of justice, in other criminal cases it does not take more than a year to get a verdict", said Elyes Ben Sedrine, former Deputy Director in charge of investigations at the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD).

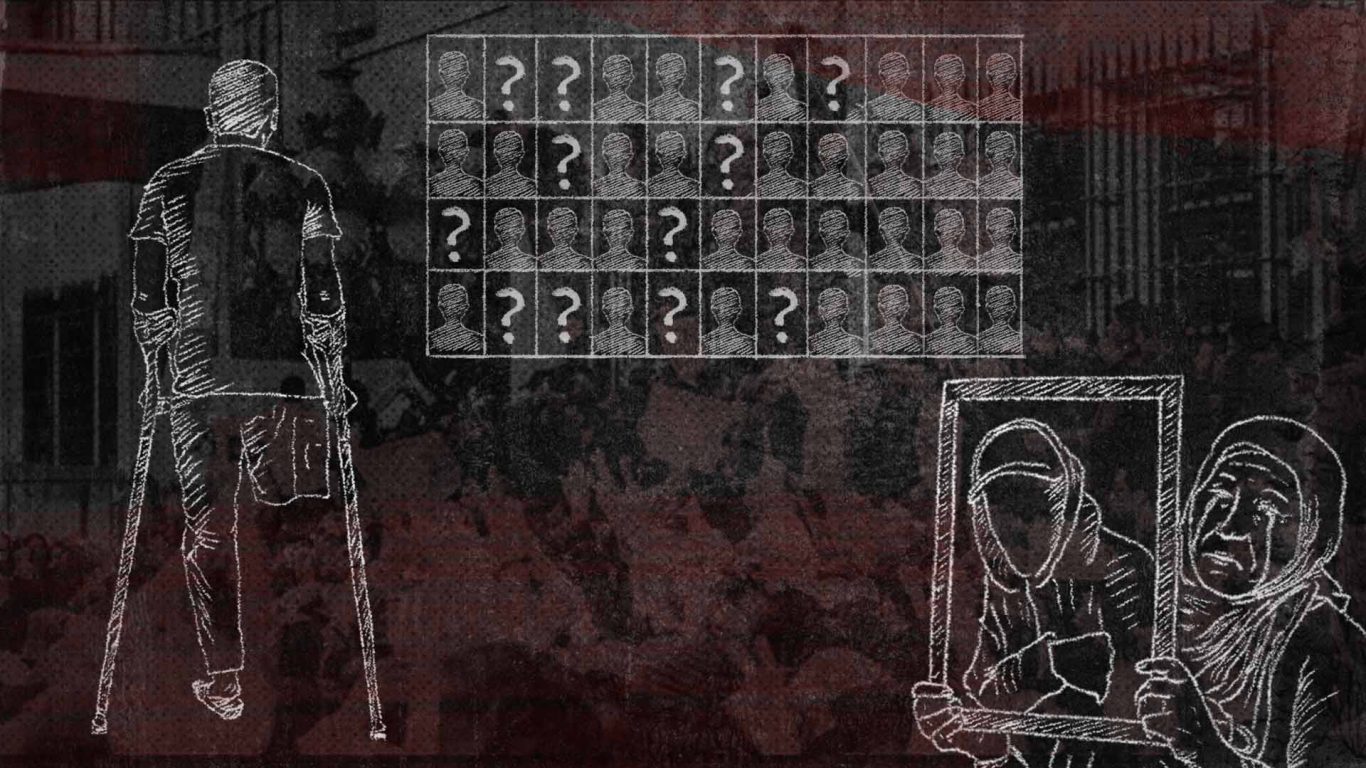

A total of 12 cases concerning the martyrs and the wounded of the Revolution are in the hands of the judiciary. These cases are among the 200 cases of serious human rights violations and financial corruption (which took place between 1953 and 2013), compiled by the IVD throughout its mandate. In 2018, the IVD was transferring these cases to specialised transitional justice chambers that sit in several courts across the country.

Charged with judging the executioners and rendering justice to the victims of the former regime's repression, these chambers are now paralysed. To date, none of them have reached a verdict. The wait has become lengthy for the victims and their relatives.

Defendants who do not Attend

At each hearing, the same scene is repeated: victims and their relatives attend the trials while the seats of the alleged perpetrators remain empty. Trials are systematically postponed and no sentence in absentia (conviction of a person without his or her presence) has been issued. "Trying in absentia in a transitional justice trial would be of no interest because the aim is to reveal the truth and preserve the memory during these trials", says Elyes Ben Sedrine. "It is important that the torturer is there, that he apologises to the victims, that he reveals the truth so we can close this chapter of the violations committed, and we move towards this reconciliation which is still pending", he adds.

At first, he courts where the specialised chambers are based summon the accused. If they do not attend, the courts issue warrants to bring them in, upon which point the judicial police are responsible for arresting the accused and bringing them straight to trial.

However, the judges have concluded that the police officers do not execute these warrants, justifying themselves by citing a lack of information on the whereabouts of the accused, even though "many of them are former executives of the security apparatus and can be easily located", and "some of them have even been spotted multiple times by the victims", according to a report that was issued by several civil society associations on the results of the specialised chambers. "In a typical case, a warrant is issued in the morning, and in the afternoon the defendant is arrested", said Elyes Ben Sedrine.

According to Elyes Ben Sedrine, there are two types of defendants in the case of the martyrs and the wounded of the Revolution. On the one hand, the direct actors: in other words, the police officers who were on the ground at the time of the events; and on the other hand: the senior officials of the Ministry of the Interior who were directing operations via the crisis cell. The latter continue to operate within the ministry or in other positions of responsibility, and Khaled Marzouki is a clear example of this. According to Elyes Ben Sedrine, the Ministry of the Interior is "complicit” in this impunity.

"Such absenteeism and the inability of the judicial system to enforce the law is largely the result of the statutory proximity between the accused and those who are supposed to guarantee their presence at trials", denounces the above-mentioned report. The authors add that "the relationship between judicial police officers and defendants seems to be marked by a deep corporatism and a certain community of allegiance".

This corporatism is something that Elyes Ben Sedrine also deplores. "The police unions have called for a boycott of the specialised chambers and have asked their subordinates not to show up and not to execute the warrants", he explains.

Inkyfada has contacted the Ministry of the Interior several times via their spokesperson and press office without any reply. Youssef Bouzakher, president of the Superior Council of the Magistracy (CSM) affirms, for his part, that the judicial police is indeed under the orders of the Ministry of the Interior, since there is no police force operating under the orders of the Ministry of Justice in Tunisia.

A Perpetual Turnover of Judges

Unfortunately, the lack of attendance of defendants is not the only obstacle to these trials being properly conducted. The perpetual transfer of judges in the specialised chambers also slows down the process. Recently, the president of the specialised chamber of the Tunis court was transferred, even though he was responsible for examining just over 60% of the cases referred by the IVD. According to the above-mentioned report, “the specialised chambers have already had some of their judges replaced by the CSM on four occasions”.

In July 2020, 29 of the 91 judges of the specialised chambers were transferred - "which is one third of them".

"Each time a judge leaves, it creates a delay", says Elyes Ben Sedrine, as the newcomer has to re-examine and familiarise themselves with the cases, and, above all, attend a training course on transitional justice before starting their work. "The CSM has been asked not to transfer the judges who are in the specialised chambers, as they have started to investigate the cases and have mastered them", he added.

This observation is shared by the president of the Tunisian Association of Magistrates, Anas Hmaidi, who does not understand this perpetual turnover of judges. He believes that by doing this, the CSM does not "preserve the importance of transitional justice".

Anas adds that the latter is also “complicit” in the stagnation of the trials, since “the change in the composition of the specialised chambers prevents them [the trials] from being properly conducted and perpetuates the impunity of the accused”.

However, Youssef Bouzakher, the president of the CSM, defends himself: "we cannot refuse judges to be promoted, it is their right". Instead, he blames the government and the parliament who "have not put anything in place to preserve both the proper conduct of trials and the right of judges to be promoted".

In addition to this, some judges face threatening situations: "They find themselves with defendants and senior officials who are still in office. We have to encourage them because they do an enormous job that is risky", says Elyes Ben Sedrine. He gives an example of a judge from a specialised court in Bizerte who was threatened by agents from the police station in the same town. She has since resigned.

Dysfunctional Specialised Chambers

Before they were handed over to the IVD following a scandal, the case files of the martyrs and the wounded of the Revolution were in the hands of the military justice system. On April 12, 2014, the Court of Military Appeal of Tunis issued verdicts for three major cases: Greater Tunis; Thala and Kasserine; and Sfax. In front of the stunned onlookers, the judge decided to reclassify the charges and to reduce the sentences, pronounced in the court of first instance, against the senior officials who had ordered either the torture or murder of demonstrators. Several were acquitted and others who were already in prison were released following the reduction of their sentences.

On the same subject

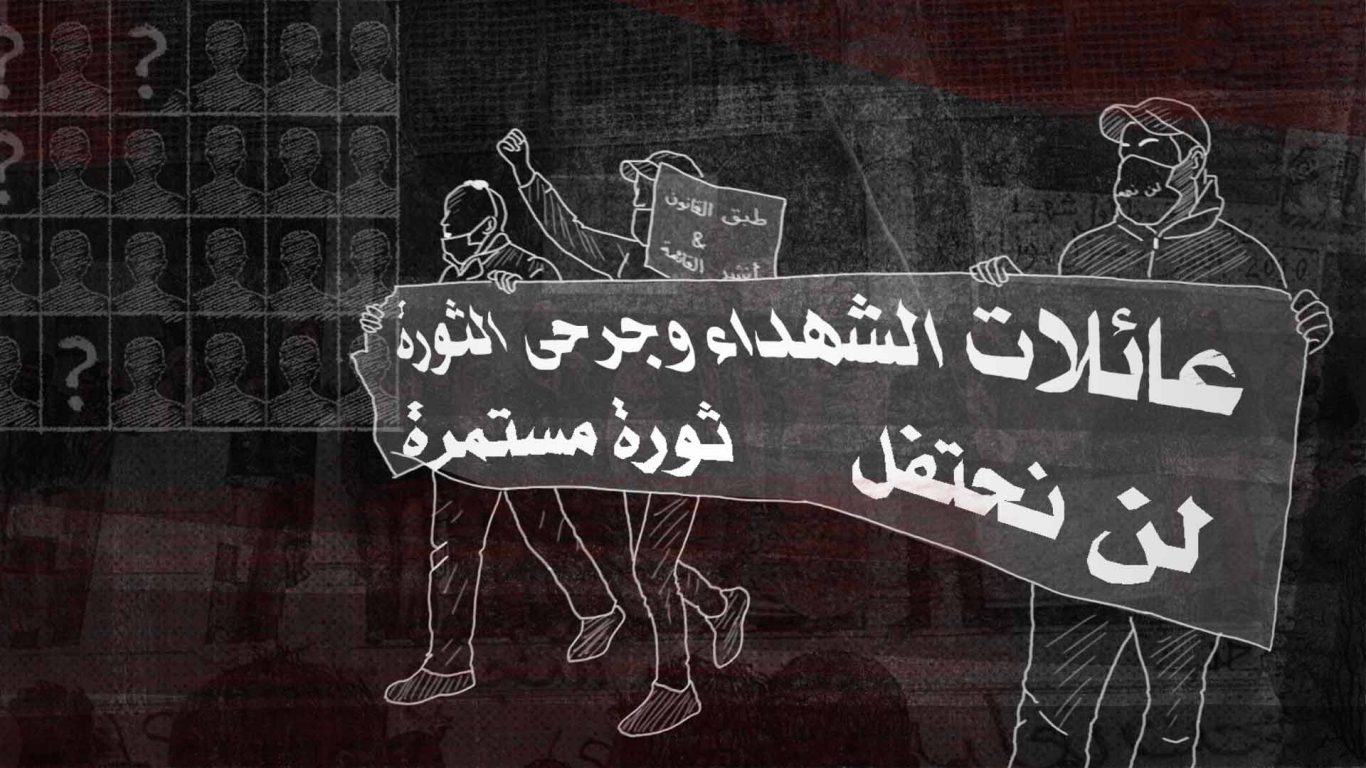

As a reaction, the families of the martyrs and the wounded recount having organised a sit-in in front of the Assembly of People's Representatives (ARP), denouncing the impunity of their torturers. "We demonstrated for two months, from April to June 2014", recalls Mimoun Khadhraoui, who was very involved. "It's a military court, they are military and police officers. So they protected each other", denounces Elyes Ben Sedrine.

According to him, the court reduced the sentences of the senior officers on the grounds of the police officers acting alone, without the knowledge of their superiors.

"However, the records of the crisis unit of the Ministry of the Interior prove the contrary. They were all aware of the situation." As an example, he chose the crackdown on demonstrators in Thala and Kasserine, which he said took place at the same time, concluding that the attack was indeed "orchestrated and organised", and that it was not "an isolated case".

Faced with the pressure and the discontent of the demonstrators, the deputies ended up adopting a law that entrusted these files to the IVD, thus setting the record straight. "It was Law 17 of 2014 that classified the acts suffered by the martyrs and the wounded of the Revolution as a serious violation of human rights. It orders the IVD to reinvestigate the cases and refer them to the specialised chambers, which is how these cases came back to us", specifies Elyes.

On the same subject

Despite the military court refusing to cooperate, the IVD managed to recover the victims' files. They “refused to send them to us despite the thirty or so letters that we sent. We had to obtain them through an informal channel, the lawyers and the victims", says Elyes.

An investigation and collection of testimonies then followed until all the files were transferred to the specialised chambers at the end of 2018.

The surge of hope that took place in 2014 when the cases were taken over by the instance is now in limbo. Some specialised chambers have recently decided to proceed to the next step: freezing the defendants' assets. "The judges tell themselves that if they touch the defendants' money, they would have no choice but to come forward", explains Elyes Ben Sedrine. For the moment, only two courts (Tunis and Nabeul) have resorted to employing this measure, and it may take some time to be implemented since it first requires "an investigation to identify the assets of the accused", says Elyes Ben Sedrine. However, he remains "optimistic" and hopes that this measure can change the course of the proceedings.