Operational since 2004, the Court has already ruled on numerous cases of human rights violations on the African continent. For instance, in 2018, the Court condemned Mali for discrimination and the violation of women's rights.

The role of the Court

Based in Arusha, Tanzania, the ACHPR is the judicial body of the African Union. It complements the African Commission's work in protecting human rights in Africa and interpreting the provisions of the African Charter. Its role allows it to issue rulings and recommendations regarding the compliance of Member States with the Charter, which they are bound to respect.

Made up of 11 judges, the Court "has jurisdiction to deal with all cases and disputes submitted to it regarding the interpretation and application of the Charter, the Protocol and any other relevant human rights instrument ratified by the concerned States". The Court may also provide advisory opinions "on any legal matter relating to the Charter or any other relevant human rights instruments".

The ACHPR may, for example, order remedial measures such as compensation or reparations. It can also order provisional measures, if a case is of "extreme gravity and urgency, and when necessary to avoid irreparable harm".

The Court operates as follows:

As a Member State, Tunisia has ratified the Protocol and signed a Declaration, along with eight other countries, allowing its citizens and NGOs enjoying observer status with the African Commission to file applications directly with the Court. This is how Ibrahim Belguith was able to bring his case against Tunisia before the ACHPR.

"I acted both as a citizen with a sense of responsibility and as a lawyer," he explains.

"Ibrahim Belguith versus the Republic of Tunisia"

July 25 was "a big change" according to Belguith. "I thought to myself, this is it, this is dictatorship". From that moment on, the lawyer would regularly check the Official Gazette and the Presidential decrees that were issued. He would also consult "UN texts, human rights conventions and, most importantly, the African Charter".

"I followed the procedure, filed my application by email and sent the original by post. But the letter was sent back to me, 'in application of a circular', that I could never find. It seems that the Tunisian Post Office refuses to deliver mail destined for Tanzania. So I had a friend send it for me from France", he recounts.

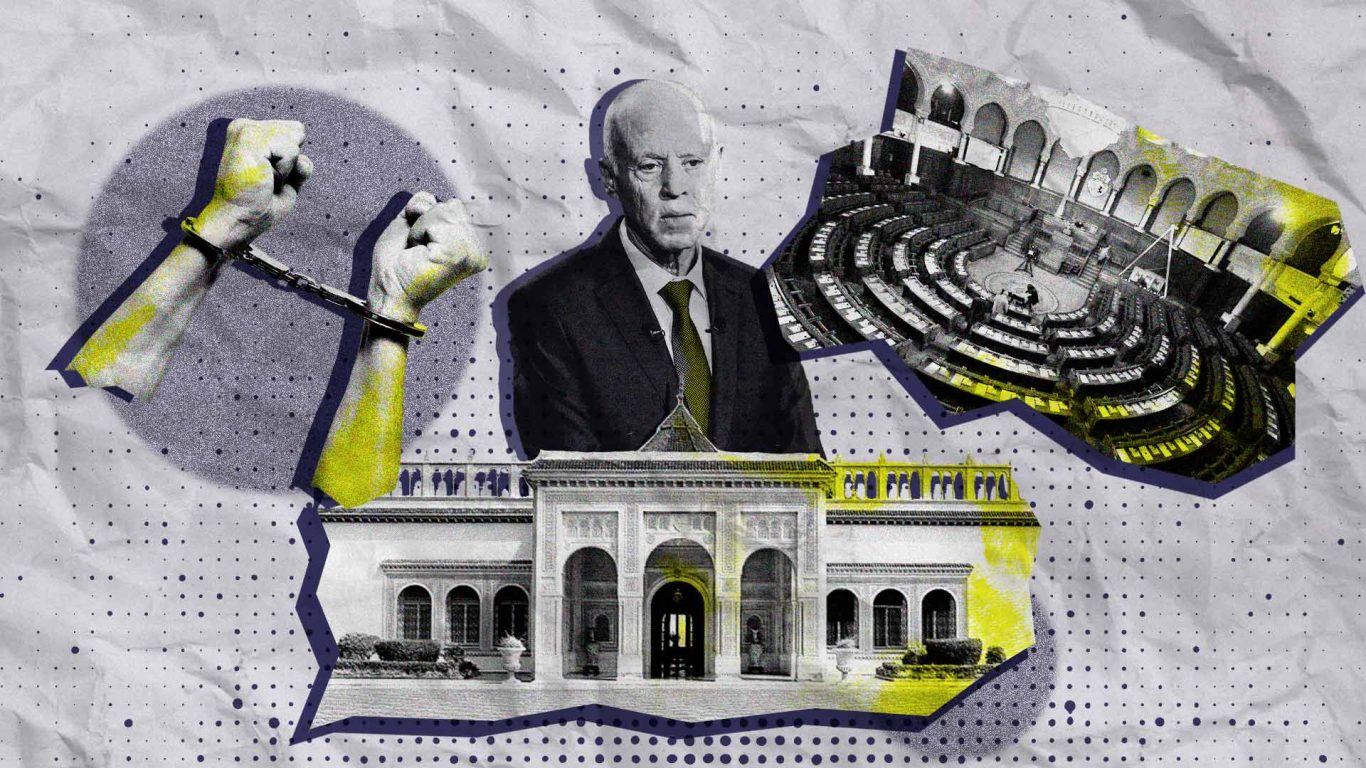

In his application, officially received by the Court on October 21, 2021, the lawyer alleged that President Kais Saied had "abrogated the Constitution [editor's note: of 2014], halted the democratic process and arrogated to himself more powers by promulgating Presidential Decrees adopted during the state of exception".

During the months following the coup, the President had issued six decrees terminating the duties of MPs and members of his government, among others. The 2022 Constitution also established a "presidentialist regime" and gave the President greater power, according to Salsabil Klibi, a specialist in constitutional law, interviewed by inkyfada in 2022.

"It's a regime where there's an imbalance of power, where the Presidency of the Republic doesn't occupy center stage but the whole political scene, while all the other institutions are merely avatars gravitating around this hub that is the Presidency," observed the specialist.

On the same subject

Once the proceedings were underway, written exchanges between Ibrahim Belguith and Tunisia - represented by Ali Abbes, State Litigation Officer, - began, with each party defending its interests and point of view.

"I didn't have any facts to prove, so it was easy for me," states Belguith. "I simply relied on legal texts. All I had to do was analyze the texts and the measures taken by the President and prove that they were in violation of Article 80 of the Constitution, which is a procedural article."

The following are the main stages in Ibrahim Belguith's appeal against the Republic of Tunisia:

Belguith argued during the proceedings, through documents he sent to the Court, that by issuing these decrees, the President and therefore the Tunisian Republic had violated the following human rights: the right of access to justice, the right to participate in the conduct of the affairs of the country, and the right to enjoy democratic values and human rights, to name a few.

As for the violation of the right to take part in the conduct of public affairs, Tunisia replied: "The Respondent State questions who authorized the Applicant to take the place of all Tunisian people [...] and requests that he produces the popular mandate given to him to act against an entire people".

The same tone was used when it came to ruling on the violation of human rights: "The Respondent State challenges the Applicant to prove the human rights which he was deprived of and how the said right was violated".

Belguith believes that the answers given by the State's Litigation Officer "are not legally sound". "They spoke as if they were before a Security Council, and argued that Tunisia hadn't committed an act of war to be questioned in this way."

The State also invoked the principle of sovereignty and non-interference to challenge the ACHPR's jurisdiction in this case: "an outside party is not allowed to interfere in cases that fall within the internal jurisdiction of the Respondent State". This stance is often adopted by the authorities when faced with international criticism, whether from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights or representatives of the European Union.

As a member of the African Union, and a signatory to the Union's conventions, Tunisia cannot, according to the Court's ruling, "raise the defense of sovereignty to circumvent or limit their obligation arising from a rule that they have voluntarily agreed to be bound by".

"The state may dominate its own territory with the help of the army and the police, but it can't do that before the African Court," says Belguith.

The Court ultimately decided not to hold an oral hearing involving both parties, and went straight to deliberations. "All the points were meticulously addressed and argued in my application, while the State merely repeated itself in its responses, so the Court decided that there was no need to go through the pleadings. I was a little scared when I found out, but I know it's a reasoned decision," Belguith continued.

After deliberation, the Court ruled in favor of the Applicant on all points on September 22, 2022. It ordered the repeal of Presidential Decrees 117, 69, 80, 109, 137 and 138 and the return to constitutional democracy within two years from the date of notification of the judgment.

Tunisia is also required to take all the necessary measures to operationalize the Constitutional Court within two years, and to remove all legal and political impediments to the achievement of this objective.

Although the adoption of the 2014 Constitution raised high hopes, its implementation is still facing a host of challenges. Persistent political disagreements, lack of consensus, and problems with appointments to the Court have left the country in a worrying institutional impasse.

On the same subject

"Democracy is not a political issue, but a legal one"

According to the Court's regulations, the State concerned by a judgment must send an "execution report" to the Registry, once the measures have been put in place. This is followed by an assessment of the state of implementation of the judgment, based on other sources. If a State doesn’t comply, this failure is mentioned in the Court's report to the Assembly of Heads of State and Government.

"However, official responses have been slow in coming since the ruling was delivered," Belguith noted. "There hasn't been any statement from government representatives on the matter. This suggests that they have no counterarguments, and that they are reluctant to make the case a public issue."

"You can't agree on a Court's jurisdiction and then reject it when you don't like the results it produces," insists the lawyer.

It seems that Tunisia is only complying with one of the ACHPR's requirements: producing a half-yearly report on the implementation of the measures ordered.

According to the reports consulted by inkyfada, Tunisia is firmly upholding the legitimacy and constitutionality of the decrees adopted by Kais Saied. The defense merely quotes verbatim from article 22 of Decree 117 - which the Court has already challenged in its ruling - regarding exceptional measures: " The purpose of these draft revisions [editor's note: political reforms] must be the establishment of a genuine democratic regime in which the people are effectively the holders of sovereignty. This regime is based on the separation of powers and the real balance between them, it enshrines the rule of law and guarantees public and individual rights and freedoms".

The State Litigation Officer also promised the impending establishment of the Constitutional Court, and mentioned "roadmaps" for ending the state of exception, referring in particular to the referendum and legislative elections.

But Ibrahim Belguith finds these arguments irrelevant: "The State's position is based on unconstitutional powers. These powers were not elected to issue simple roadmaps".

Tunisia is actually struggling to comply with the Court's requirements. The Parliament has recently promised to establish the Constitutional Court "as soon as possible".

And yet, in reality, a "0 millimes" budget was allocated to the creation of the Court in the 2023 Finance Law. According to the lawyer, "there is no willingness to set up the Constitutional Court in the future".

The Tunisian State's lack of action can be explained by the very essence and scope of the African Court. As a matter of fact, it does not represent a binding power. As analyzed in article 30 of the Protocol by the International Federation for Human Rights, "The execution of judgments by States is obligatory but voluntary".

There is also no mechanism in place to follow-up on the execution of the Court's decisions, and the Protocol does not currently provide for any coercive measures to ensure their enforcement.

In addition, the task of monitoring the execution of the Court's rulings is assigned to the Executive Council of the African Union, which is composed of all the Foreign Affairs Ministers of the Union's Member States. This is why, in the words of Benjamin Kagina, PhD student in law, "this political monitoring regime [...] has remained opaque with questionable effectiveness."

"It's also the problem of the African Commission. They are subordinate bodies, constrained by their representatives. There's a tendency to think that democracy is a political issue, when it's actually a legal one", says Belguith.

Going forward, if the ACHPR considers that Tunisia has started to implement the measures, it will require a further report within the next six months, until it is satisfied and confident that the measures have been effectively taken.

But if the Court rules in favor of Belguith once again, and declares that Tunisia has refused to comply and continues to be unconstitutional, it will have to mention this in its report to the Union.

This will lead, according to the lawyer, to "the possible freezing of Tunisia's accession to the Union, and it will certainly be prevented from participating in the Union's bodies".

He asserted, however, that his objective was "to ensure that any sanctions imposed by the Court are targeted at those responsible".

Despite everything, Belguith is "delighted" that the relatives and children of political prisoners are taking their case to the Court. "It's a great thing that Tunisians are aware that there is a legal body on a continental level, where people can claim their rights. These are flagrant violations of human rights, and I can only hope that they win their case," he added. "After all, if we take these cases to the Court, we're also doing so as a matter of principle, for the sake of history".