But six years later, the legislative process is still running without a Constitutional Court, and since July 25, 2021, this organ is cruelly lacking.

"We have no defence against authoritarianism", Sana Ben Achour alerts.

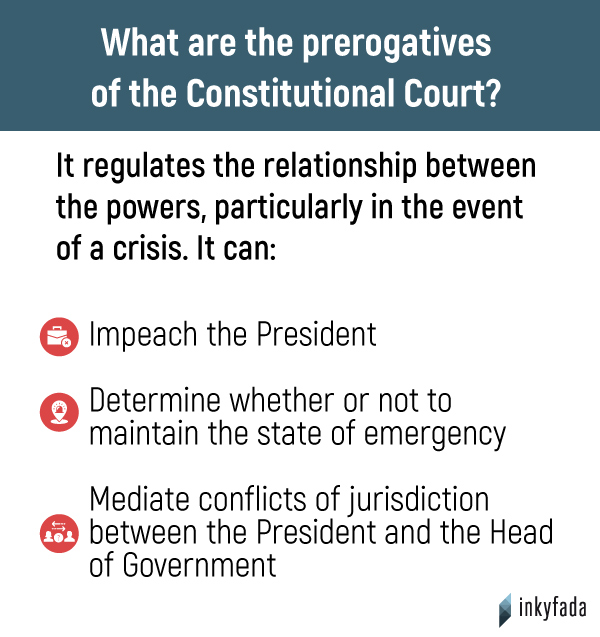

Indeed, in the absence of constitutional judges to be called upon by the President of the Assembly or by a group of 30 MPs to determine the time limits of the state of emergency, there is no counter-power to limit the full powers of the President over time.

On the same subject

repeated delays

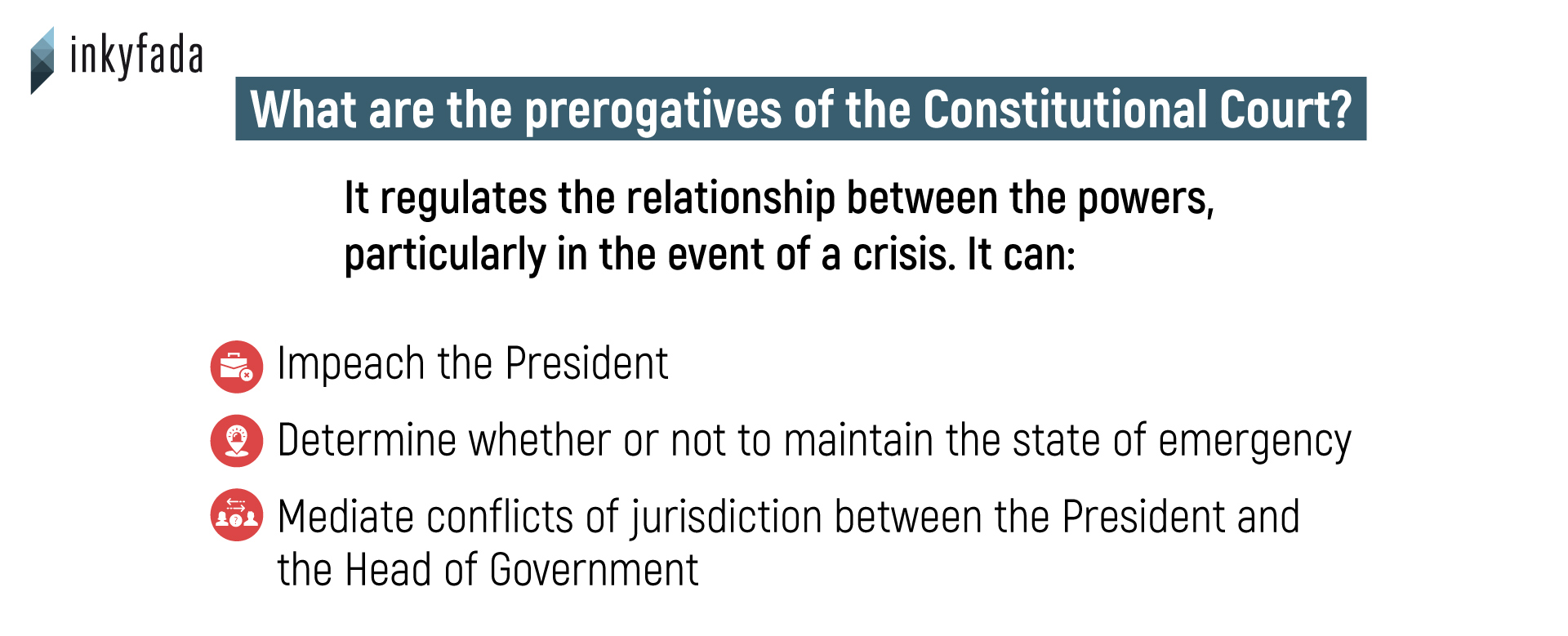

As a pillar of the republican system, the Constitutional Court has the prerogative to control whether laws and treaties comply with the Constitution, but also to impeach the President if accused of a serious violation of the Constitution by a two-thirds majority of the Assembly; to determine whether a state of emergency should be maintained or not; and to mediate in conflicts of jurisdiction between the President and the Head of Government.

While waiting for this organ to be set up, a provisional authority for the control of the constitutionality of laws has been created. But as its name indicates, it has only one jurisdiction: to verify that the laws that are passed are in line with the Constitution. Therefore, it cannot regulate other authorities in the event of a crisis, or rule on the constitutionality of old laws.

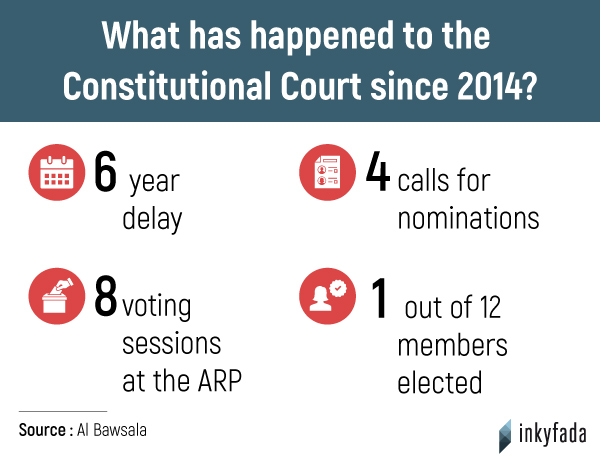

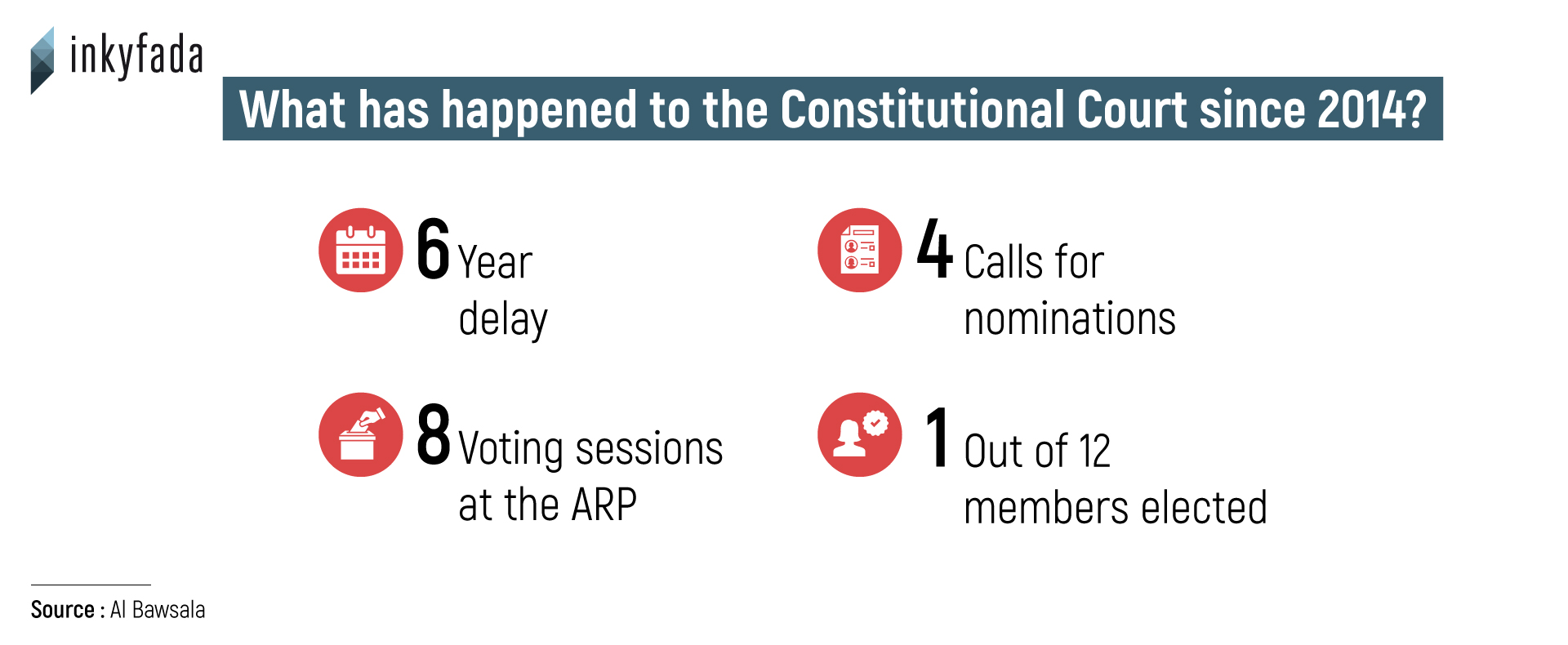

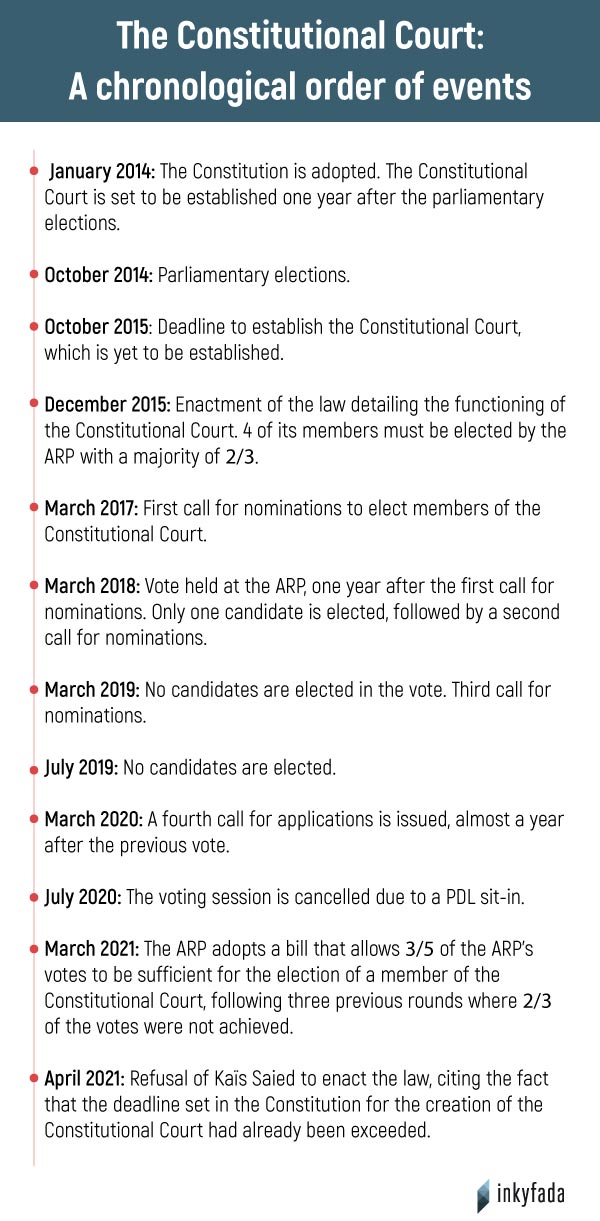

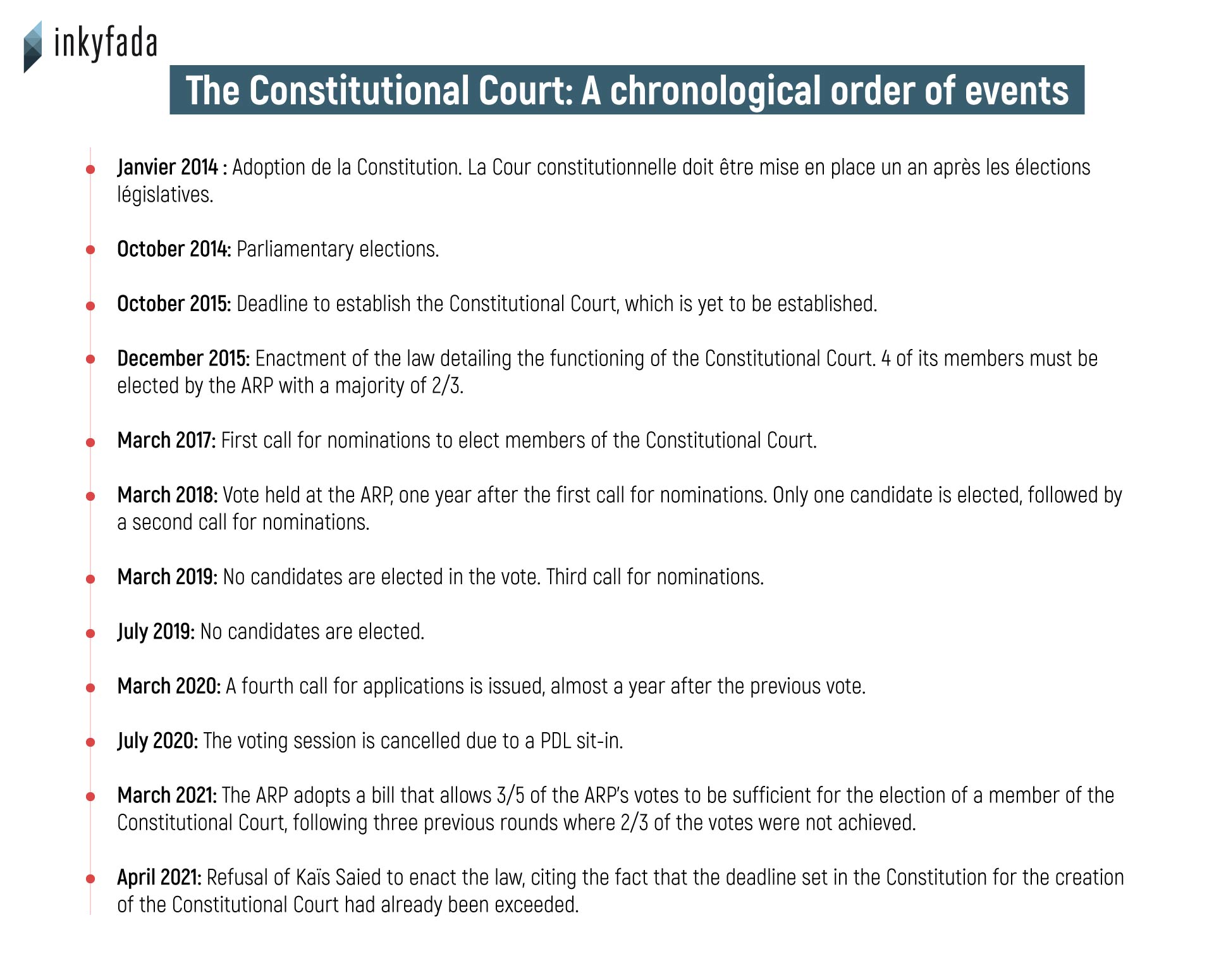

Sana Ben Achour, who has been following the issue since its inception, traces the obstacles to its implementation back to the time of the National Constituent Assembly and the drafting of the Constitution. When it was elected in October 2011, most of the parties that made up the Assembly pledged to complete its drafting within a year, "but its work has been considerably delayed due to repeated crises". The basic law was not passed until two years later, in January 2014.

In January 2015, a commission was tasked with drafting a law defining the functions of the Constitutional Court. "It was very delayed, even though they had plenty of time to prepare", parliamentary observer Mahdi Elleuch comments. The organic law was finally adopted in December 2015, already falling behind on the constitutional deadline.

A PARLIAMENTARY MAJORITY IN DISAGREEMENT

Out of the 12 members of the Court, four must be elected by the Parliament. Then comes the turn of the Superior Council of the Magistracy and finally the President of the Republic, each of whom must successively appoint four members.

To be elected by the Assembly, a candidate must receive two-thirds of the votes, equivalent to 145 votes. However, the Court has never been able to get through Parliament, which is crippled by political disputes. The largest point of contention centres around the choice of candidates for the Court. "This is the issue that has crystallised all the tensions", confirms Sana Ben Achour.

It was not until 2017 that a first list of candidates was presented to the MPs. The parliamentary groups managed to reach a consensus on four members, all of whom were legal specialists. "The names were publicly announced to the media, even before the vote took place", recalls Mahdi Elleuch. "But at the last moment, the Nidaa Tounes party, and probably Ennahdha, retracted their names", he adds. Only one out of four candidates was eventually elected the following year, the only one who received the votes of the parliamentary majority: Raoudha Ouersighni. This conservative judge, who was put forward by Nidaa Tounes, was also the "perfect" candidate for Ennahdha, according to the lawyer.

"This incident is proof that Ennahdha and Nidaa Tounes [the two allied parties that formed the majority in parliament] are the ones responsible for the failure to set up the Court. The parliamentary majority was large enough to be able to elect the members of the Constitutional Court on its own, so there was no reason for it to be impeded. Except that this majority never wanted a Constitutional Court, because it feared that this organ would one day turn against them", says Mahdi Elleuch. According to him, these blocs would have used the secret nature of the vote to absolve themselves of any responsibility afterwards.

Since then, the list of candidates has been changed three times, without any agreement in Parliament.

"There was a sort of conviction among the entire political class that there would be no Constitutional Court", the lawyer continues.

During the organic law debates, "there were many attempts to reduce the jurisdiction of the Court to the bare minimum. This again reflected the distrust of the ruling coalition towards this organ", he adds.

A CONSTITUTIONAL COURT IN ENDLESS DELAYS

According to the Organic Law of the Constitutional Court, "each parliamentary bloc in the Assembly of People's Representatives (...) has the right to submit four names to the plenary session". Furthermore, the law clearly states that to be a member, one must "not have held any central, regional or local partisan responsibility or been a candidate of a party or coalition in the presidential, legislative or local elections for ten years prior to his or her appointment to the Constitutional Court".

"There has been an abusive interpretation of the organic law from 2015 on the Constitutional Court, which allows parliamentary groups to claim the right to present their candidates", Sana Ben Achour maintains. According to her, this interpretation creates ideological issues in the Court, with each camp seeking to position its representatives, and trampling on the principle of neutrality of its members.

"While MPs were waiting for this organic law on the Constitutional Court, the coalition sought to put in place tailored laws for its candidates. This was the case, for example, when they wanted to present Habib Khedher, a lawyer affiliated with Ennahdha and the nephew of Rached Ghannouchi, leader of Ennahdha, at all costs. They had made a very dangerous law proposal, which allowed for the nomination of candidates who belong to political parties, and who do not meet any conditions of neutrality or non-membership" , explains Mahdi Elleuch.

Many MPs also saw the requirement of a two-thirds majority for electing members of the Constitutional Court as a major stumbling block. "This is not really the problem, there are many examples that contradict this argument", the parliamentary observer refutes. For example, in 2017, Parliament had to elect (by two-thirds, 145 votes) three candidates to the Council of the Independent High Authority for Elections (ISIE), as well as the president of the same authority by an absolute majority (109 votes). "The three candidates for the Council were elected very easily, while there was a huge block on the president, the election of which required fewer votes. It is really a question of political will."

On the same subject

Moreover, the establishment of the Constitutional Court has not been a priority on the parliamentary agenda. According to Mahdi Elleuch and the Al Bawsala association, in six years, there have been less than ten voting sessions in the ARP dedicated to electing members of the Constitutional Court.

Several sessions were cancelled without being rescheduled. In July 2019, for example, the fifth parliamentary session ended without the final round of voting for the third call for nominations, and nominations were not reopened until six months later. Similarly, a session due to be held in July 2020 was cancelled due to an LDP sit-in, without being rescheduled, resulting in no voting session taking place during the second parliamentary term.

The parliamentary blocs also regularly exceeded the deadlines for nominating candidates, which contributed to delays in sorting and reviewing the nominations, and prevented more voting sessions from taking place.

In order to overcome the obstacles, the Assembly of People's Representatives adopted a bill proposed by the Attayar party in March 2021 to make the election of the members of the Court more flexible. The idea was to lower the majority threshold to three-fifths of deputies, meaning 131 votes would be needed instead of 145. But despite the consensus of the Parliament, President Kaïs Saied subsequently refused to pass the law, citing the fact that the constitutional deadline for setting up the Constitutional Court had already been exceeded.

For Mahdi Elleuch, "this interpretation makes no sense. When the Constitution has been violated once, it is not something to be repeated". This argument implies that the Constitution has to be revised, which cannot be done without the Constitutional Court. "There is no way out."

However, even if the bill had been passed into law by the President, "this does not mean that the establishment of the Constitutional Court would have been swiftly accomplished. There would still have been additional and difficult steps", he concludes.