At the foot of a building a bit further down, two men are resting on some artificial grass. Abdulrasoul, a Sudanese exile who left his country several years ago, is sitting next to them. "We are exhausted, we have no food or assistance", he says calmly. Over two months of sleeping outside is "too much", he exclaims with a sigh.

Today, their main demand is to be evacuated from Tunisia and be resettled in a "safe" third country.* The UNHCR does have such a programme, but it is extremely selective: only 76 people who were in Tunisia were resettled in other countries during 2021. "The decision on resettlement is taken by the resettlement countries", the UNHCR website states.

Constant protests in Zarzis since February

Although the protesters arrived in Tunis not long ago, the demonstration initially started in Zarzis on February 9, with several migrants converging at the UNHCR offices of the south-eastern town. A sit-in took place in front of the office, protesting against the expulsion of several refugees and asylum seekers from a UNHCR shelter in Medenine. They later managed to enter the perimeter of the villa and set up camp in the courtyard. In the meantime, the squatters were joined by other migrants.

After occupying the space for more than two months, inkyfada went there to meet them. In the shade of an olive tree, several men describe their already precarious living conditions. Amongst them is Abdulrasoul, who was one of the first to join the camp.

"We have no toilets or bathrooms", he says, pointing to the only water pipe available for the 200 people. "Prefabs have been opened to shelter the most vulnerable people, such as women with young children", but the rest of them sleep outside. The general exhaustion is already palpable.

The protesters only have a few blankets and mattresses that are spread out in the courtyard of the villa. In the middle of the camp, a white sedan and a white 4x4 with the UNHCR logo blend into the background. The limited shelter created by the vehicles ensures that the people sleeping there get some shade, as the temperature has already exceeded 30 degrees several times.

Despite this, solidarity seems to be the order of the day. Some children play in the middle of the courtyard while their parents keep a watchful eye. When it comes to food, those who have work bring in some money. "We combine a few dinars and cook together", Abdulrasoul explains.

Negotiations took place between the UNHCR and the exiles at the beginning of April, says one of them. "They offered us financial assistance and to return to the hostel while they process our cases", she says. However, the offer was not convincing, so they decided to demonstrate in front of the UN agency's headquarters in Tunis.

"We had to go to Tunis to assert our rights and get help."

"The refugees have lost confidence", says Romdhane Ben Amor, spokesman for the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights (FTDES), who has been following the case from the very beginning. "After three months under inhumane conditions, they are asking them to return", he continues. The exiles "know that this will happen again".

At the root of the protests: deportations from the Medenine shelter

In Zarzis, inkyfada also met Mohamed, a shy-looking young man who also left Sudan a few years ago. After going through chaos in Libya, he tried to cross over to Europe, but was intercepted by the Tunisian coast guard.

On the same subject

Once disembarked, he was offered the opportunity to apply for asylum to obtain refugee status. Tunisia is a signatory to the 1951 Convention relating to the status of refugees, but "it does not have a national law on the right to asylum", explains Romdhane Ben Amor. "It is therefore the UNHCR that deals with granting this status", he adds.

On the same subject

He accepted and was taken into the care of the UNHCR as an asylum seeker. The application process is lenghty, sometimes lasting several years. "It's a question of the credibility of international law", explains Laurent Raguin, the deputy representative of the UNHCR, further specifying that the duration or the process is necessary to establish whether the applicants correspond to the criteria for obtaining refugee status.

Mohamed has been staying in the Medenine shelter for several months. Laurent Raguin explains that the shelter is a temporary solution, one that is primarily used to accommodate people intercepted at sea by the Tunisian National Maritime Guard, as well as those who are most vulnerable, such as "single women, minors and the disabled".

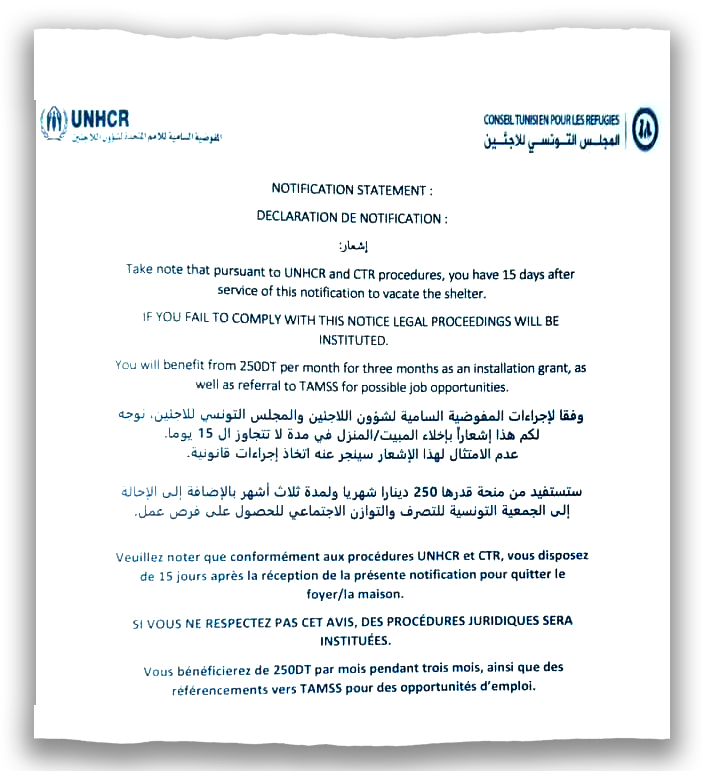

Everything started to get complicated in January when Mohamed and some of his fellow asylum seekers and refugees each received a document stating that they would be deported. The letter was sent to them by the UNHCR and the Tunisian Refugee Council (CTR). "Take note that pursuant to UNHCR and CTR procedures, you have 15 days after service of this notification to vacate the shelter", the document (consulted by inkyfada), explains in French, English and Arabic. These decisions were issued without the possibility of appeal.

"If you fail to comply with this notice legal proceedings will be instituted", it continues to state in capital letters. However, the document also specifies that they will "benefit from 250DT per month for three months as an installation grant, as well as referral to TAMSS [a Tunisian employment association] for possible job opportunities".

From his office in Lac 2, a UNHCR representative refutes the way the facts are presented. "Ultimately, no one was deported", he says in response to the word being used in the interview. When people move into the shelter, "they are asked to sign a document, they are told that it is not indefinite, and that after a number of weeks, a number of months, they will have to leave", he says. "They have been asked to leave for months and months, even years for some, to make way for people who are much more vulnerable."

"Of course, we don't just throw them out on the street", he specifies. Financial assistance for housing is provided, as well as support in finding a job, "we tell them: try to get a job, try to be independent".

A lack of UNHCR protection

The UNHCR representative laments that many of the "less vulnerable" young people refuse job offers. "They put themselves in a situation to make us assist them", he says. When asked about these job offers, he acknowledges that they often lack a legal framework. "We do a lot of work with the government to try to legalise the employment contracts, but it is very difficult."

He also acknowledges that the working conditions of these jobs are far from simple. "It's not some office work in the bank next door, that's for sure, but there are job offers and people can work", he argues.

In fact, these working conditions sometimes lead to the workers dying. For example, on August 12, 2021, Saber Adam Mohamed, a 26-year-old Sudanese refugee, was killed in a workplace accident in a plastics factory in Megrin.

"He found this job via the UNHCR and its partners", Romdhane Ben Amor explains. "It was an undignified job. He worked longer hours than the Tunisians and was paid less", the FTDES spokesman says, according to testimonies he collected from the young man's relatives.

In addition to the difficult working conditions, Mohamed also states that he suffers from discrimination: "Some employers ask if you are Christian or Muslim, and if you are Christian they don't give you your money", he says. "It doesn't encourage you to work." For him, the shelter was the ' only place' where he felt "safe" because of 'the community'.

"But the shelter is not enough to protect us", says Abdulrasoul, describing abusive behaviour by UNHCR shelter guards, who sometimes prevent refugees from leaving. "There are many testimonies about the behaviour of UNHCR staff, especially those who are in direct contact, perhaps due to a lack of training", Romdhane Ben Amor confirms.

According to him, there is a general lack of assistance from the UNHCR. "The means provided for refugees and asylum seekers are not up to their expectations, whether in terms of access to accommodation, financial aid, UNHCR contributions for access to healthcare and education, and access to work", the FTDES spokesperson explains.

He specifies that this problem is not new and recalls, for example, that in March 2019, a 15-year-old Eritrean attempted suicide in the Medenine centre. At the time, the FTDES already criticised the "deplorable conditions that are increasingly deteriorating".

"Migrants face insufficient food, hygiene, difficulties in accessing necessary health care and a lack of information on their fundamental rights", FTDES statement, March 18, 2019.

Laurent Raguin does acknowledge that "not everything is perfect". He believes that the UNHCR works with limited means, specifying in particular that "with Covid, humanitarian funds have decreased globally". According to him, the UN agency should not be alone in managing this situation. "We are asking the government and other partners to get involved, it has to be a collective effort", he urges, as if a call for help.

Tunisia - a safe country?

For all these reasons, the protesting exiles hope to be evacuated and resettled in another country. "Our problem is not money or housing, we have to leave this country", says Abdulrasoul.

He does not consider Tunisia to be a safe country. "I survived the genocide in Darfur and then I witnessed the Islamic State's atrocities in Libya and I don't feel safe in Tunisia", he tells inkyfada. "We are facing a racist society."

He recounted several cases of aggression against his fellow exiles, including a child in a Tunisian school who had allegedly been locked in a bathroom by his classmates. During one of the interviews during the sit-in, the inkyfada team also witnessed racist remarks being hurled at the exiles from a car.

"Tunisia is not a safe country, even for Tunisians", says Romdhane Ben Amor. He points out that the country "does not have an arsenal that can guarantee the rights of refugees and migrants", and lacks social safeguards.

He believes that since July 25, the situation has become even more worrisome for refugees, referring to the statements of several UN representatives regarding their concerns about Tunisia. He additionally cited the case of Slimane Bouhafs, an Algerian refugee in Tunisia, who was abducted and exfiltrated to his country of origin where he is now imprisoned.

Meanwhile, Laurent Raguin maintains that Tunisia is considered "a safe country for asylum". "Those who have the papers [asylum seeker or refugee status] are protected", he said, adding that the Tunisian authorities recognise the status of "asylum seeker" and "refugee" as it is defined and issued by the UNHCR, in the absence of a national law on asylum.

He adds that the Tunisian authorities are very cooperative and that the situation is much better in Tunisia than in other countries. "After all, Tunisia has been a mixed population for 3,000 years, it's extraordinary", he says.

The UNHCR and "the implementation of the migration policies of Northern States"

Romdhane Ben Amor also reports that there is " criticism of the process for obtaining refugee status". In fact, according to him, the UNHCR sorts migrants by nationality, especially when they arrive in Tunisia after being intercepted at sea.

Citizens of countries that are considered to be 'refugee-producing' countries, such as Sudan or Eritrea, are referred to the UNHCR and offered asylum in Tunisia, while those from other countries are referred to the IOM as they are considered migrants. In this case, assessment "is not done on an individual basis", says Romdhane Ben Amor, and "they exclude certain nationalities" of the right to seek asylum.

Laurent Raguin argues the opposite. "The fundamental principle of the UNHCR is that we meet the person face to face", he says, "it is not done on the basis of groups or nationalities except in major emergencies such as the one Ukraine". However, he acknowledges that a form of sorting is indeed carried out upon arrival: "with the IOM and the Red Crescent, we try to separate people who are potential migrants from others who are potential asylum".

In his opinion this practice is justified, because: when these people arrive, "we have to act quickly". "People are rescued at sea and are extremely traumatised, they have to be looked after. The difficulty is that all these discussions take a lot of time", he says, pointing out that, afterwards, cases handled by the IOM are redirected to the UNHCR and vice versa.

"The referral between the UNHCR and the IOM does not seem to depend solely on the will expressed by the person", explains Sophie-Anne Bisiaux in " Politique du non-accueil en Tunisie", a joint report by FTDES and the Migreurop network on the non-reception policy of migrants in Tunisia.

Some people who expressed their wish to apply for asylum were in fact redirected to the IOM and denied access to the UNHCR. As an example she cites the case of a Nigerian family who had to "wait for nine months before they got to meet a UNHCR staff member and file an application for asylum".

According to her assessment, the UNHCR adopts a "strategy of sorting and separating the 'good refugees' from the 'bad economic migrants'". Sophie-Anne Bisiaux considers the High Commissioner for Refugees to be "complacent" in "implementing the management and security policies of European states".

On the same subject

"For several decades, in order to ensure funding, this UN agency has integrated the migration policies of the Northern states and has, in order to achieve its objectives, accepted the mechanisms of migration control: sorting populations, biometric identification, encampment, pressure on beneficiaries, accompanied by all the associated violations of the fundamental rights of migrants", Sophie-Anne Bisiaux concludes.