For years, many agreements have been signed to readmit expatriated Tunisians from Europe, most notably with Italy and Belgium. In addition to these bilateral partnerships, the European Union uses its migration funds to finance numerous programs in Tunisia within the "mobility partnership" framework. In practice, these programs serve primarily to prevent people from leaving and encourage them to stay in their country of origin.

These programs, which are set up between European States and the EU, are numerous and difficult to trace. In other countries, notably Nigeria, journalists have tried to track the various flows of European funding under the name of migration. According to subsequent reports, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to fully grasp all of the funds, programs, and actors involved.

In the words of Maite Vermeulen, Ajibola Amzat and Giacomo Zandonini, this is a “deeply worrying” matter. "Although Europe aims to maintain a semblance of transparency, it is virtually impossible in practice to hold the EU and its member states accountable for their migration expenses, let alone evaluate their effectiveness."

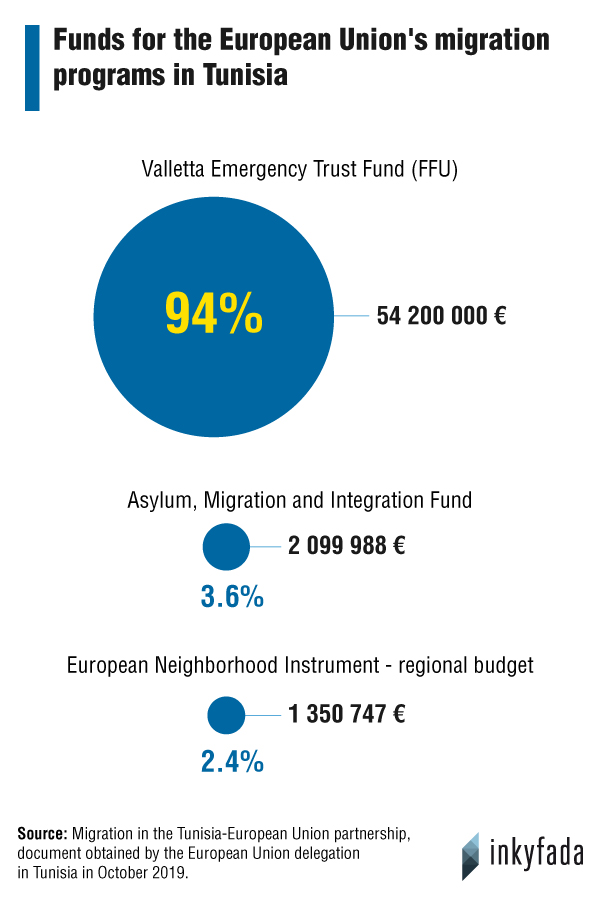

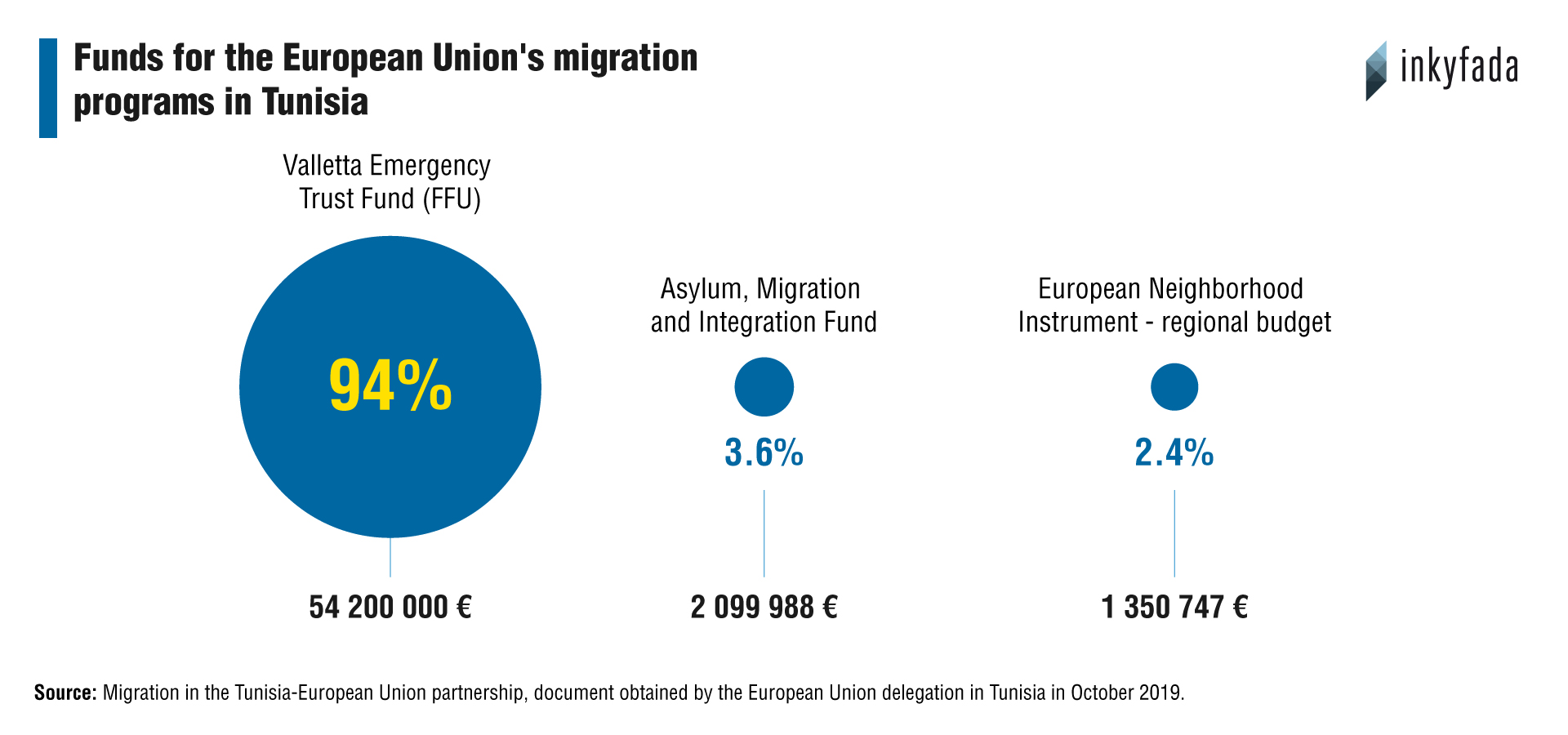

In Tunisia, where funding remains lower than in other countries in the region (such as Libya), it was possible to obtain a summary of EU-funded programs related to migration from the Delegation of the European Union. Fifty eight million euros across three different funds: the Valletta Emergency Trust Fund (UTF), the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) and the regional European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI).

However, it should be noted that this information does not take into account various other investments in development or counter-terrorism whose objectives may also relate to migration. Since 2011, at a bilateral level, the European Union has invested 2.5 billion euros in Tunisia, all areas considered.

The overwhelming majority of this EU funding (€54,200,000) is provided by the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. Launched in 2015 at the Valletta Summit, this EUTF was created "for stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa to promote stability and economic opportunities and to strengthen resilience” to the sum of €2 billion for the entire region.

This funding has been criticized by human rights organizations such as Oxfam, emphasizing that "a considerable portion of its funding is invested in security measures and border management."

“These results show that the approach of European donors to migration management is rather geared to containment and control. This falls short of their commitment (...) to ‘promot[e] regular channels for migration and mobility from and between European and African countries’ (...) or to ‘facilitate orderly, safe and responsible migration and mobility of people,’” the report explains.

Border control

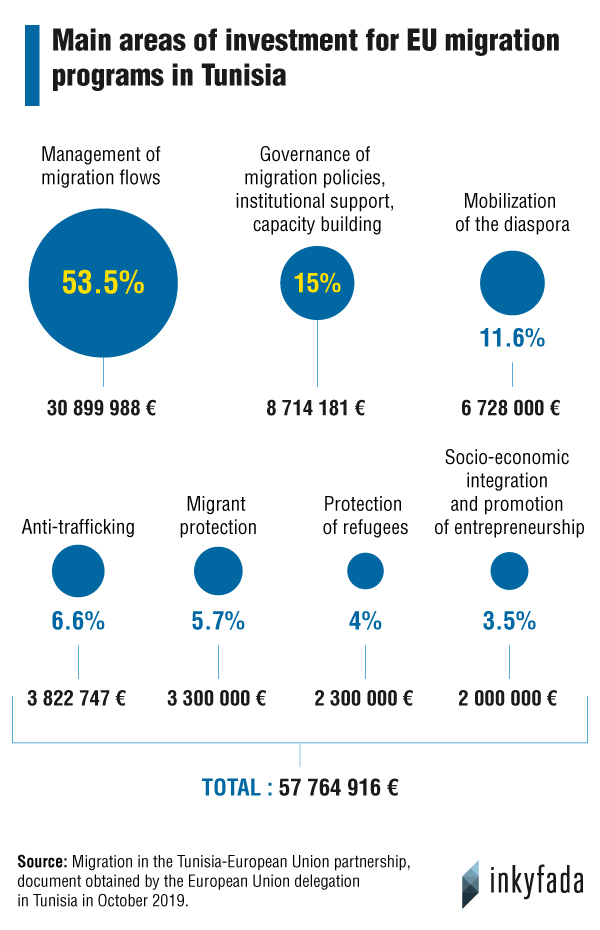

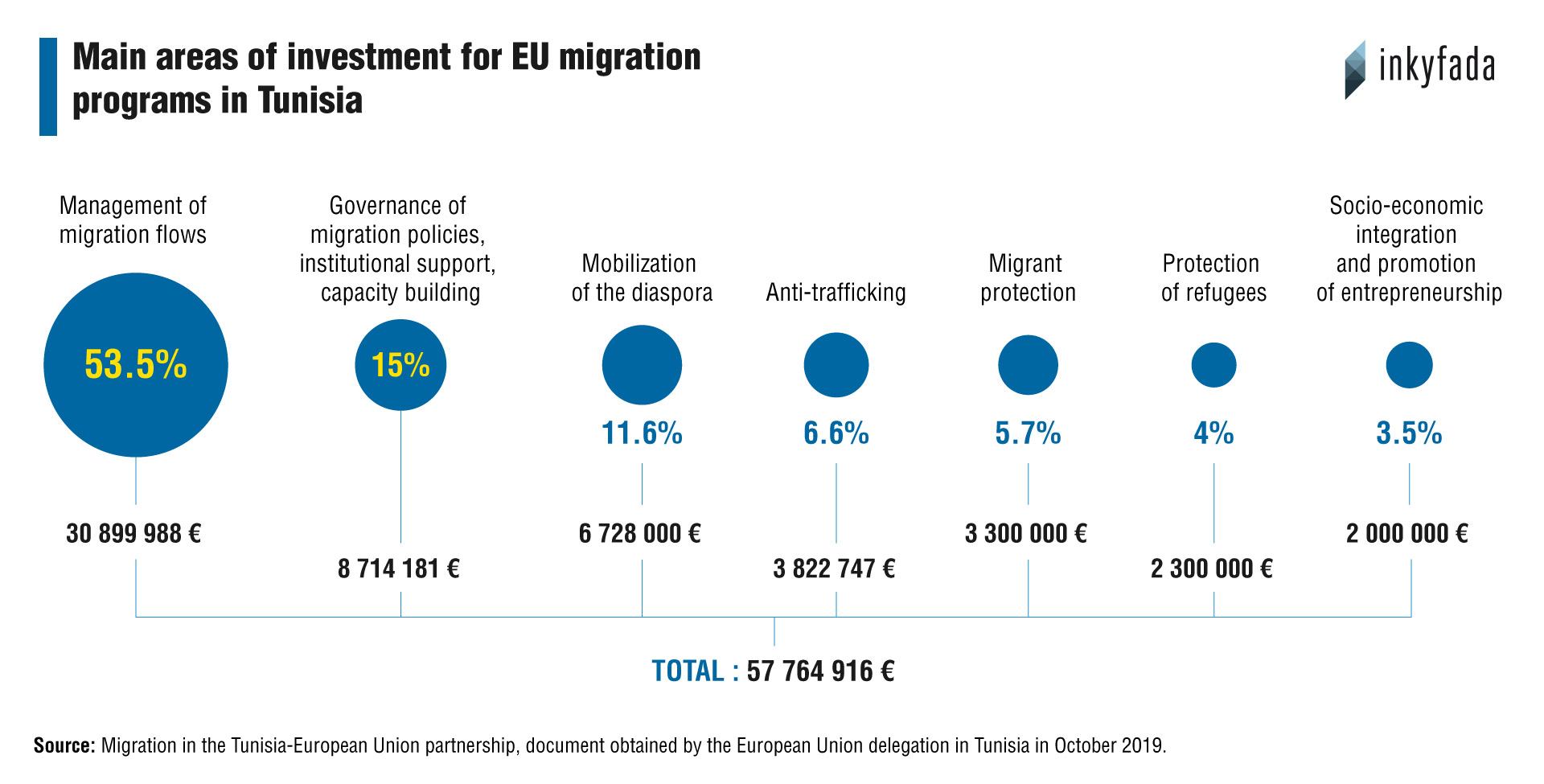

Among the 20 or so projects financed by the EU, border control is a significant priority, and the Border Management Program for the Maghreb Region (BMP Maghreb) is by far the most costly. In order to provide the Tunisian Coast Guard with equipment and training, the EU is investing €20 million, nearly a third of the entire budget in question.

The BMP Maghreb project has a clearly defined objective: to protect, monitor and control maritime borders in order to reduce irregular migration. For example, the Tunisian National Guard has been provided with three operational centers and a pilot maritime surveillance system (ISmariS). In collaboration with the Ministry of Interior and its various bodies - national guard, customs, etc. - this program is run by the ICMPD (International Centre for Migration Policy Development).

"The BMP Maghreb is set up in Morocco and Tunisia and is essentially the acquisition of computer or transmission equipment requested by the Tunisian State," explains Donya Smida of ICMPD. "We started off by calculating the requirements, which were subsequently met by the Tunisian authorities."

Supplying various equipment is on top of the extensive training conducted by technical experts, both of which are managed by the ICMPD. This international organization presents itself as a specialist in "capacity building" within migration policy, and "far removed from emotional and politicized debates."

"This stance is indicative of a more general semantic shift. Treating migration as a political topic seems risky, so we prefer to ‘manage’ it as a purely technical matter. Essentially, 'managing' it first and foremost means to depoliticize the migration issue," says Camille Cassarini, a researcher on sub-Saharan migration in Tunisia. "The ICMPD is a border management organization which aims to provide expert training to nation states, focusing on political and ideological neutrality and technical support."

In addition to this program, Tunisia benefits from further funding and equipment to help ensure border security. Some of these benefits are encompassed by other EU-funded projects in fields such as counter-terrorism.

One should also not forget about the equipment provided by individual European countries under their bilateral agreements. For example, in the name of border control, Italy personally provided Tunisia with a dozen boats in 2011. In 2017, Italy additionally supported Tunisia in a project to modernize patrol boats supplied to the Tunisian National Guard for around 12 million euros.

Germany is also an increasingly important investor, particularly in regards to national borders. Between 2015 and 2016, they helped found a regional center for the national guard and border police. Furthermore, they provide electronic surveillance equipment such as thermal cameras, night-vision goggles, etc. at the Tunisian-Libyan border.

The ambiguity of bilateral Agreements

Many European countries (Germany, Italy, France, Belgium, Austria, etc.) cooperate with Tunisia on numerous migration agreements. A large portion of these agreements concern the readmission of deported Tunisians. Between 1998 and 2011, four agreements of this nature have been signed with Italy alone. According to the FTDES* (the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights), the most recent of these agreements states that Enfidha airport in Tunisia is to receive two planes of deportees per week from Palermo.

"On the surface, these agreements focus on reciprocity, but in reality the relationship is unequal and asymmetrical. When it comes to readmission, it's clear that the majority of deportations concern Tunisians in Europe," says Jean-Pierre Cassarino, researcher and specialist in readmission procedures.

In practice, Tunisia does not always show political commitment to implement the agreements in question. Several European countries complain about the slowness of the Tunisian state's readmission procedures, with which "interests are not exactly aligned."

Nevertheless, signing these agreements is a means of consolidating alliances for Tunisia. "It’s a way to be seen as a reliable partner, particularly in the fight against religious extremism, illegal immigration and the external protection of European borders, all of which have become key priorities since about halfway through the 2000s," Jean-Pierre Cassarino explains.

According to researchers, these bilateral agreements have become increasingly informal since the 1990s in order to avoid long ratifications at the bilateral level, thus making them more ambiguous.

soft power: A new method of outsourcing

All these examples illustrate the extent to which the issues of border control and illegal immigration are central to European policies. In a study from 2016 by the European Parliament's General Directorate for External Policies, it is highlighted how the EU "tends to support its own interests in agreements, as is the case with immigration-related issues" in Tunisia.

The study emphasizes contradictions in EU rhetoric, which since 2011 has insisted on its willingness to support Tunisia’s democratic transition (particularly in the area of migration), while it remains very much focused on the security aspect in practice.

"Security-related cooperation remains heavily focused on controlling migration flows and combatting terrorism" while "EU rhetoric on security issues (...) has evolved into a broader discourse on the importance of reinforcing the rule of law and ensuring protection of the rights and freedoms obtained through the revolution," the report notes.

Even though these projects are of lesser financial importance, the EU is setting up a number of programs aimed at “developing socio-economic initiatives at a local level” and “mobilising the diaspora,” or even "raising awareness of the risks of irregular migration." The main priority is to deter potential illegal migrants in advance through institutional support, awareness campaigns, etc.

Institutional support (presented as an EU priority) is the second largest area of investment, accounting for almost 15% of the funds.

Houda Ben Jeddou, head of international cooperation on migration at the DGCIM at the Ministry of Social Affairs, explains that the ‘ProgreSMigration’ project (established in 2016 with 12.8 million euros in funds), enables "training workshops," "return facilitation schemes," and "statistical surveys on migration in Tunisia."

This project is in collaboration with Tunisian state actors such as the Ministry of Social Affairs, the National Observatory of Migration (ONM) and the National Institute of Statistics (INS). One of its major elements is to "support the Tunisian National Migration Strategy." However, this type of project is not a priority for Tunisian authorities and the initiative has still not seen the light of day.

Houda Ben Jeddou explains that she submitted a project to the chairmanship in 2018 which is still awaiting approval. "There is no political resolve to prioritize this issue," she acknowledges.

For Camille Cassarini, this standstill is quite indicative of the lack of coherent policy in Tunisia. "It speaks volumes about the circumvention strategies that the Tunisian state implements by refusing to advance the issue politically," he says. “Despite European investments to encourage Tunisia to implement a migration policy that aligns with their standards, it is clear that the agendas don't match up at this level."

Changing the approach to migration

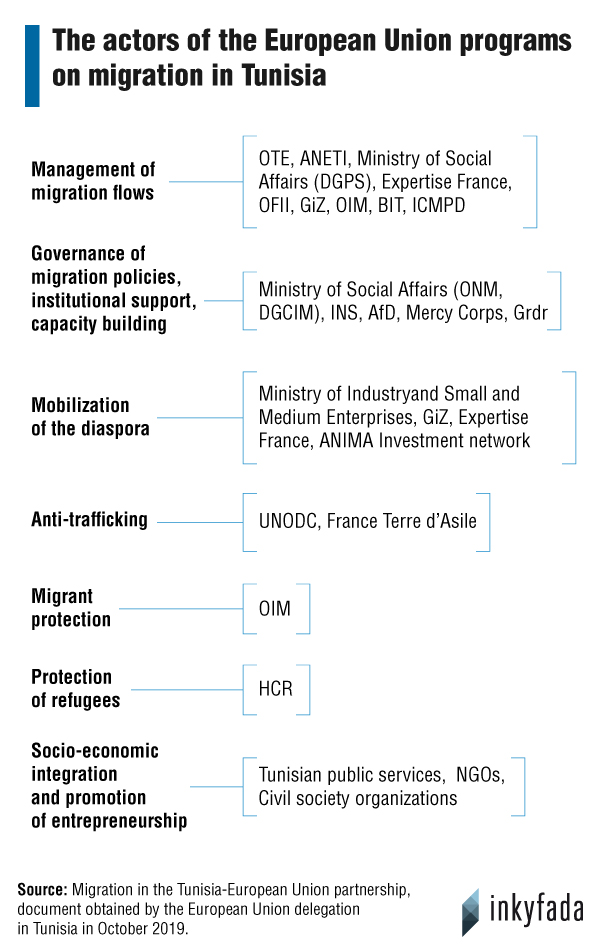

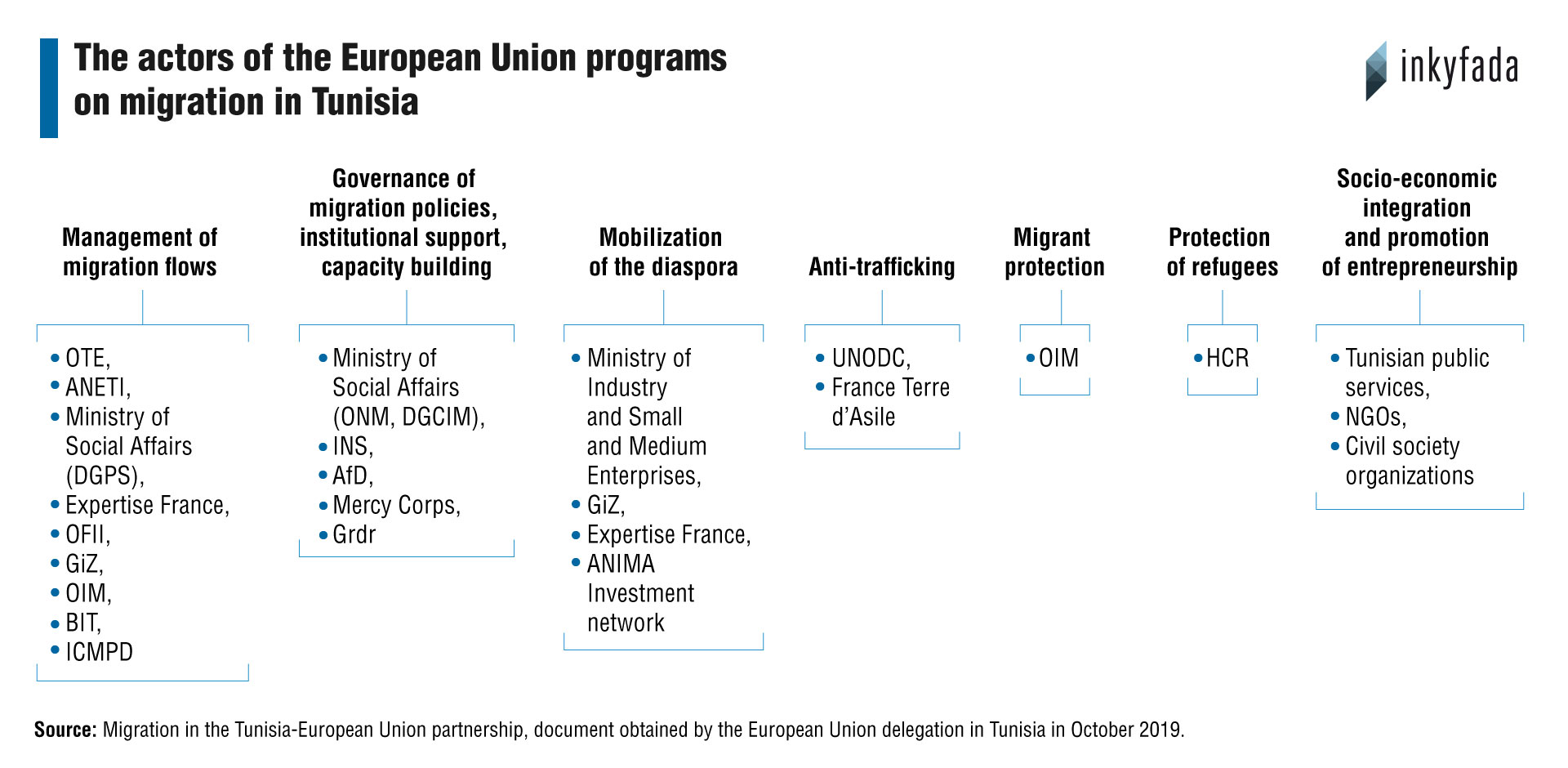

In order to establish all these programs (in addition to state collaborations with Tunisia), Europe works closely with international organizations such as the IOM (International Organization for Migration), ICMPD and UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), regional European development agencies (such as GiZ, Expertise France, AfD), as well as Tunisian civil society.

In his work, Camille Cassarini demonstrates that security actors are gradually being assisted by humanitarian actors, who in turn are pursuing a migration management policy that aligns with the security policies. "The role of these international organizations (such as IOM, ICMPD, etc.) is mainly to effectuate norms and practices that reflect methods of migration control that European states can’t directly implement themselves," he explains.

Contacted several times by Inkyfada, the Delegation of the European Union in Tunisia responded by simply providing the document detailing their projects (within the framework of the mobility collaboration with Tunisia). They did not wish to respond to any interview requests.

By funding these organizations, European states have all the more sway in political guidance, he continues, taking the IOM (one of the main active organizations in Tunisia in the field) as an example. "Thanks to their networks, these organizations have become key players - and in Tunisia they occupy an organizational space that has been left unoccupied by the Tunisian state. This arrangement more or less suits everyone: European states get actors who convey their approach to migration, and the Tunisian state gets actors who handle this issue in its place."

"In our academic language, we call them epistemological actors," adds Jean-Pierre Cassarino. Through language usage and the mere scope of their network, these organizations manage to impose their specific approach to migration management in Tunisia. "You simply have to look at the migration lexicon published on the website of the National [Tunisian] Migration Observatory: it's a copy of the IOM lexicon," he continues.

Also approached by Inkyfada, the IOM did not respond to our interview requests.

Camille Cassarini also gives the example of "voluntary repatriation." The IOM and the French Office of Immigration (OFII) state that these programs allow for "the social and economic reintegration of returning migrants in such a way as to guarantee the dignity of the individuals." "In actuality, most repatriations are monitored very poorly or not at all. They are sent back to their country without any resources, thereby increasing their economic precariousness and vulnerability," he says. "And all these key words euphemistically underline the reality of cooperation and programs that are first and foremost rooted in migration control.”

Although the IOM has existed in Tunisia for nearly 20 years, Camille Cassarini explains that this system was primarily implemented after the Revolution, especially through civil society. "Tunisia's singularity is its democratic transition: the EU had to adapt its migration policy to this political change, and this was done in particular through the promotion of civil society."

In their forthcoming book "Externalising Migration Governance through Civil Society: Tunisia as a Case Study," Sabine Didi and Caterina Giusa explain how European programs and international organizations are being implemented through civil society.

"In the case of migration-related projects, the crucial role of civil society appears at the micro level as an intermediary between: the organizations in charge of implementation, and the various groups categorized and identified as 'return migrants,' 'members of the diaspora,' or 'potential candidates for irregular migration'," explains Caterina Giusa in the book. "The point of including and working with civil society is to 'force-feed' [local populations]," she says.

"To summarize, all of these projects aim to ensure that Tunisian actors have an understanding of the migration issue that is aligned with the interests of the European Union. And in practical terms, what is emerging behind this ‘managerial’ approach is above all an injunction to stand still," concludes Camille Cassarini.