The letter that Leïla Ladjimi Sebaï handed to Audrey Azoulay that day alerted her to the number one threat to the archaeological site of Carthage: illegal constructions.

To the detriment of the archaeological heritage site, this plague, which the Ben Ali clan itself participated in during the dictatorship, still continues today. A large proportion of these constructions are not being demolished, and their creators remain unpunished.

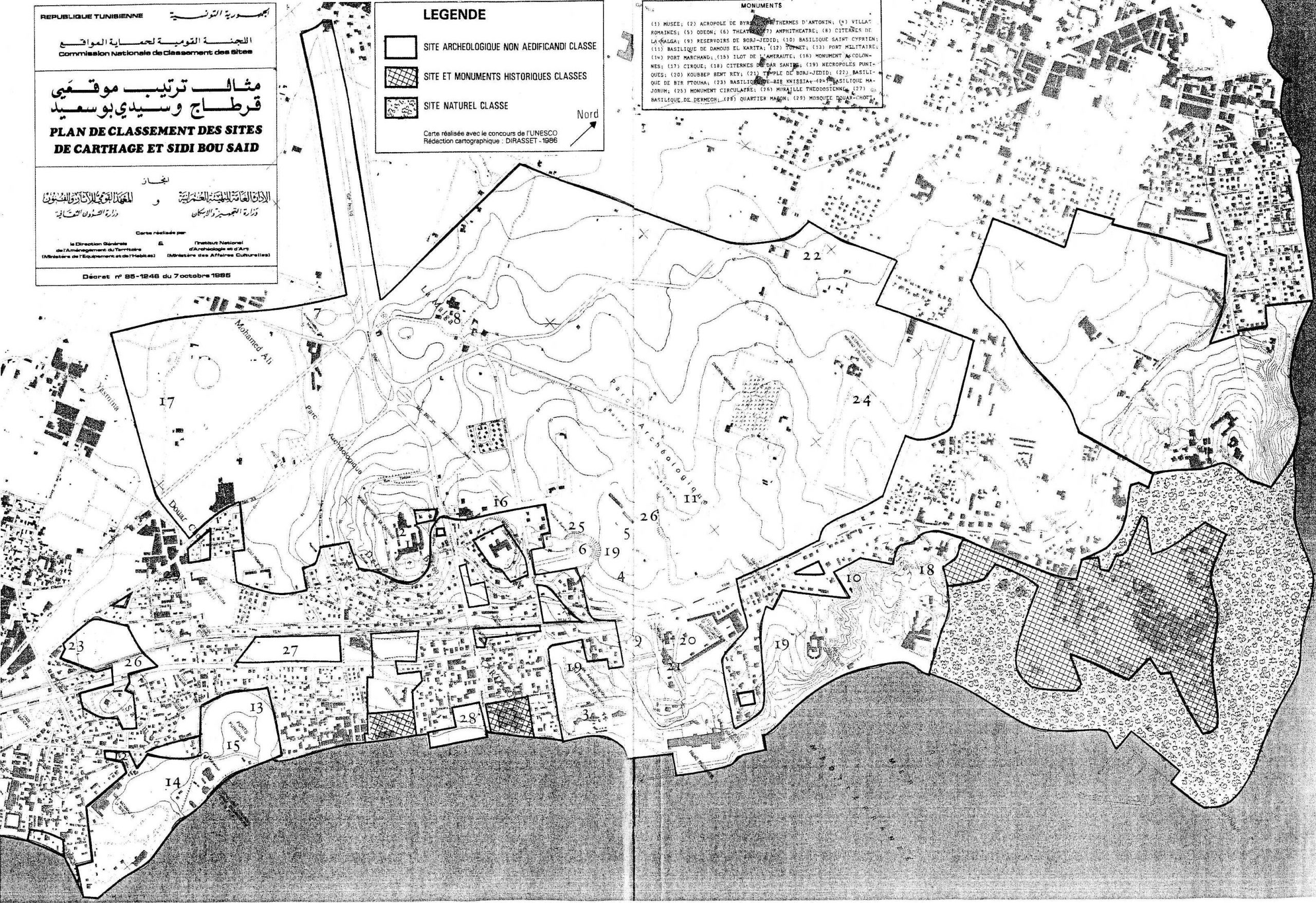

The main areas where illegal construction has taken place over the past years. Source: Plan attached to decree n°85-1246, relating to the classification of the Carthage site.

THE FADING ROMAN CIRCUS

A simple stroll is enough to see that modern houses stand side by side with ancient ruins in Carthage, providing a disorienting scenery. The listing of the site as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979, and its classification in 1985, were not enough to slow down the urbanisation of the archaeological zone.

According to Unesco, it is the area where the second largest Roman circus in the world is located that is most affected: almost a third of the site is currently covered with houses.

The mayor of Carthage, Hayet Bayoudh, and the chief custodian of the site, Moez Achour, say that since the revolution, these so-called popular habitats have multiplied, which is confirmed by a 2012 UNESCO report.

Waste and constructions at the Roman circus, 2019. UNESCO / C. Dunning.

Waste and constructions at the Roman circus, 2019. UNESCO / C. Dunning.

IN THE SHADOW OF THE BEN ALI-TRABELSI CLAN

During the dictatorship, the Ben Ali-Trabelsi clan were already abusing the archaeological zone. This information was only revealed after the revolution: the former President had declassified a total of 12.5 hectares* of archaeological zones by decree between 2006 and 2007 "in order to carry out residential projects".

The Hannibal housing estate, a project developed by members of the Ben Ali-Trabelsi family, was thus able to see the light of day. The fall of the dictator did not also lead to the fall of the luxurious villas which still populate the Bir-Ftouha district today.

The villas of the Hannibal housing estate in Bir-Ftouha. 2019. UNESCO / C. Dunning.

The villas of the Hannibal housing estate in Bir-Ftouha. 2019. UNESCO / C. Dunning.

In March 2011, after an intensive mobilisation of the Friends of Carthage, all the declassification decrees issued under Ben Ali were repealed, and a commission in charge of regulating the situation of the lands concerned was established.

But reaching an agreement remained complicated. Abdelmajid Ennabli, custodian of the site until 2001, and Jellal Abdelkafi, urban planner in charge of designing a protection and enhancement plan for Carthage, were part of this commission, which met on numerous occasions between 2011 and 2014.

"There were two attitudes. The first was: it's illegal, we're demolishing everything. The second was: what was constructed stays constructed, and construction on the remaining land is prohibited", recalls Jellal Abdelkafi.

Abdelmajid Ennabli, a supporter of the firm solution, adds: "the commission wanted to distinguish between buyers acting in bad faith and buyers acting in good faith". In other words, the buyers who were complicit in the violations on one side, and those who were victims and to whom the land was sold at a high price on the other.

The two men say that the various members were unable to reach an agreement, so they sent a list of proposals to the Head of Government, for him to decide. However, they add that ever since the report was submitted in 2014, no decision has been reached.

Following the Bir-Ftouha case, the 2019 Unesco report recommends "setting up a map with the private plots, in order to have a general overview of the land that it would be necessary to acquire in the medium or long term". The fact that a large part of the archaeological zone is privately owned encourages further violations, since construction is prohibited while sale is permitted.

According to Moez Achour, progress has been made in this respect. "The Tunisian state, through the Ministry of Cultural Affairs and the National Heritage Institute (INP), devotes a yearly budget for the acquisition of archaeological land", he says. According to Unesco, six plots were acquired between 2018 and 2019, including one in the Roman circus.

The reign of impunity

The Heritage Code stipulates that any person who constructs in the archaeological zone is liable to a prison sentence of one month to one year and/or a fine of 1,000 to 10,000 dinars. The text also specifies that "the perpetrators of the violations are obliged to restore the damaged historical monuments and buildings and to repair the resulting damage". Identical penalties are stipulated for "anyone who voluntarily authorises construction on archaeological land".

Legally, it is impossible to condemn those who have constructed in Bir-Ftouha, since the land had been declassified at the time, and the construction therefore was legal. "The people who bought an apartment, a villa, or a piece of land, are not responsible for the fraud, they bought badly acquired property, they were deceived", says the town planner Jellal Abdelkafi.

When asked about the application of the article to the ongoing constructions, the director of the INP, Faouzi Mahfoudh, replies: "If ever, after the demolition order, the construction continues, of course the INP will initiate legal proceedings. If the construction stops, there is no longer an infringement of the law."

In other words, it is the failure to comply with the demolition order that is sanctioned, but not the fact of having constructed in an archaeological zone.

AN EQUALLY concerned URBAN AREA

In the urban zone, where construction is not prohibited but monitored, there are many applicants: according to the municipality's figures, there were no less than 182 construction applications submitted between 2018 and 2020.

The regulations that apply are aimed at preserving the unity of the landscape and the ruins within it. In addition to restricting the number of floors, for example, it is almost always required to have a positive opinion from the INP, which carries out both impact studies and excavations.

In general, a construction permit is eventually granted, but it can take several months for the preventive archaeology team to examine the ruins and protect them. "Burying them under a layer of sand and avoiding the pouring of concrete or pillars helps to preserve them", explains Moez Achour. Thus, owners may have to modify the plans of their house to preserve the heritage, for example by raising it.

Many violations are therefore also recorded in urban areas, between those who extend their houses without authorisation and others who simply lose patience with the duration of the excavations and start constructing without waiting for a positive opinion.

Source: Carthage Municipality

A PROBLEM of Enforcement

Since the beginning of her mandate in July 2018 and up until April 2021, Mayor Hayet Bayoudh has recorded 73 illegal constructions. The problem is that only 43 demolition orders have been enforced over this period.

Between the identification and the demolition, a multitude of actors intervene. The INP, under the supervision of the Ministry of Culture, is responsible for monitoring the archaeological zone. In the event of an infraction, a report is sent to the Carthage town hall, which issues a demolition order. However, for this order to be enforced, it is necessary to obtain the approval of the Ministry of the Interior, on which the Carthage municipal police depend.

According to various sources, this is where the problem lies. "The reports are there, the municipality is alerted, the mayor issues the demolition orders, so what is missing? The enforcement!", Moez Achour says indignantly.

In order to find a solution, he participated in several meetings with the municipal police, organised by the governor of Tunis. The mayor of Carthage confirms this: "the problem is always with enforcement".

The Ministry of the Interior itself did not set a very good example in 2018, as it constructed a sports complex for the police academy in the middle of the archaeological zone.

The construction site of the Police Academy, 2019. © UNESCO / C. Dunning.

The construction site of the Police Academy, 2019. © UNESCO / C. Dunning.

Following pressure from UNESCO, the work was halted and one of the buildings partially demolished.

However, the damage to the heritage site is irreversible: a structure dating back to Antiquity, corresponding, according to an archaeologist, to a harbour annex, was partly demolished during the construction work, the chief custodian deplores.

In addition to the passivity of the police, it is the State's inability to compensate the inhabitants that slows down the execution of demolition orders, according to the mayor of Carthage: "The people there tell you 'this is my house, this is all I own, if you destroy it, you're going to leave me on the street'. When you demolish, you have to find a solution. Compensation or rehousing all these people somewhere else."

On the same subject

The issue was raised by Unesco as early as 2012, and a solution was proposed: to relocate the occupants of the circus area to housing estates built at the expense of the INP. However, according to a 2019 UNESCO report, the project has been abandoned.

PREVENTION RATHER THAN REPARATION

According to the president of the Friends of Carthage, the municipality should act much more proactively: "Why do we have to go as far as demolition orders for newly and illegally built houses? It is the role of municipal and administrative officials to stop illegal construction immediately, and to not let citizens incur unnecessary expenses, often very large sums, only to have them taken away afterwards."

The association tries to help in its own way by alerting people to the excesses it detects. This led to the president being summoned to the police station three times, following complaints from people whose illegal activities the association had denounced.

Moez Achour also says he receives alerts from the delegate of Carthage or the presidential guard. "Even the workers have to inform if they discover an infraction, it's everybody's business, because it's really a delicate subject in Carthage", he adds. The INP is doing its best to prevent the houses from spreading, but the surveillance team consists of only six or seven people. One guard works especially at weekends, when construction is most common.

A PROTECTION PLAN: THE MISSING PIECE

The Heritage Code provides for a mechanism to protect the archaeological site, called the Protection and Enhancement Plan (PPMV). This is a document delineating the different zones of a cultural site and the regulations that apply in each one. "It will allow Carthage to finally be saved from the ferocious appetite of a few speculators, and will put this great site at the disposal of the greatest number, that is to say first of all of the local residents, the Tunisian citizens, the public, and visitors of all kinds", declares Leïla Ladjimi Sebaï, president of the Friends of Carthage, who is campaigning for the implementation of this plan.

"There was a classification plan for the site of Carthage-Sidi Bou Saïd, but this plan has no operational value, it classifies between what is archaeological, natural, and urban. Meanwhile, the PPMV is a legal text", explains Jellal Abdelkafi, who has been in charge of drawing up this plan since the 1990s.

Although he presented the first version in 2000, the document has yet to be approved by the authorities.

"At the time, during the Ben Ali regime, when we entered into the real estate speculation procedures, no more commission meetings were possible. That was it.", says the town planner. Since then, the approval of this plan is still at a standstill.

A TUG OF WAR

BETWEEN HERITAGE AND URBAN PLANNING

The approval of the PPMV presupposes a prior agreement on the delineation of the site, and it is precisely on this point that tensions have crystallised for ten years.

The decree establishing and delineating the site of Carthage has to be signed by the Ministry of Culture, in charge of heritage, and the Ministry of Public Works, in charge of urban planning. "These two have never managed to reach an agreement", states the mayor of Carthage, who has participated in several meetings.

According to Moez Achour and Jellal Abdelkafi, the Directorate of Urban Planning (which is part of the Ministry of Public Works), wants to remain faithful to the 1985 plan at all costs. "The delineation of the territory classified by the 1985 decree was drawn freehand on a set of plans at [a scale of] five thousandths. As a result, the lines cut a house in two, and crossed a street. The 1985 decree is good because it sets the procedure in motion, but it is not usable", explains Jellal Abdelkafi.

Classification plan of Carthage-Sidi Bou Saïd from 1985.

Classification plan of Carthage-Sidi Bou Saïd from 1985.

"The debate was: do we adapt to the reality of the terrain, by tracing the fences of the houses or the streets, or do we faithfully try to reproduce 1985?" Moez Achour summarises.

Last July, after the UNESCO visit, discussions were reopened, and it was clearly the Public Works Department that won the argument. "We are going to adopt the 1985 plan as it is, and we will just try to create markers that correspond to the reality of the terrain", reports Moez Achour. Once the topographic map is ready, if the two ministries can agree, the PPMV can be approved.

During the last decade, the succession of ten ministers of culture and nine ministers of public works has not made things any easier. The procedures have been disrupted several times by such reorganisations.

While a new government is about to be put in place, the delineation of the site and the approval of the PPMV is a priority according to the actors on the ground.

"If Carthage is left in its current situation, in five years' time there will be no archaeological site left", the site's chief custodian warns.

UNESCO: WARNINGS WITHOUT CONSEQUENCES

In 2019, a note was sent by the Minister of Culture to the Head of Government "informing him of the possibility that the property might be registered on the List of World Heritage in Danger [defined by Unesco, editor's note] and asking him to request the authorities concerned to proceed to enforce the demolition permits".

So far, UNESCO has never made good on the threat. "For Carthage, this possibility of being put on the List of World Heritage in Danger was not considered useful because there was always the possibility of resorting to other measures to deal with the difficulties encountered", explains Karim Hendili, programme officer for culture at the Unesco office for the Maghreb.

Since 2012, Unesco has regularly asked Tunisia to provide status reports on the conservation of Carthage. The last one, which Tunisia demanded not to be made public, dates from January 2020, and the next one will be required in December 2022. The organisation also puts forward solutions in its own progress reports, but only issues reminders when they are not implemented - which happens frequently.

When asked about the lack of sanctions against the Tunisian state, Karim Hendili replies: "Sanctions are not a useful option in the field of heritage conservation, regardless of the site concerned. The essence of the Convention is to achieve the noble and complex objective of sustainable preservation of properties, by promoting cooperation at both national and international levels."

While Unesco can put pressure on its member states, notably with the threat of declassification, and offer technical support or help in mobilising funds, its texts are clear on the matter of responsibility: "The State which intentionally destroys cultural heritage of great importance to humanity, or which intentionally fails to take appropriate measures to prohibit, prevent, stop and punish any intentional destruction of such heritage, shall bear the responsibility for such destruction."

Abdelmajid Ennabli, former custodian of the site, who fought to have it listed as a world heritage site, laments the lack of political will, something he holds as primarily responsible for the Carthaginian disaster. The 80-year-old bitterly recalls the words of UNESCO's director-general in 1972, which still apply fifty years later: "We have to save Carthage".