Every day starting at dawn, dozens of families equipped with food baskets, queue up for an appointment to visit their loved ones. Often, they have travelled several hundred kilometres, on a night train or with a rented car. Once inside the prison, they have to patiently wait for several hours until it is finally their turn, and they hear the announcement: “ 5 minute visits, not one minute more”. Only 5 minutes, and another long wait. It is here, in this prison, that 10% of the Tunisian prison population* is detained, including a large number of individuals charged (pending trial or already convicted) for terrorism.

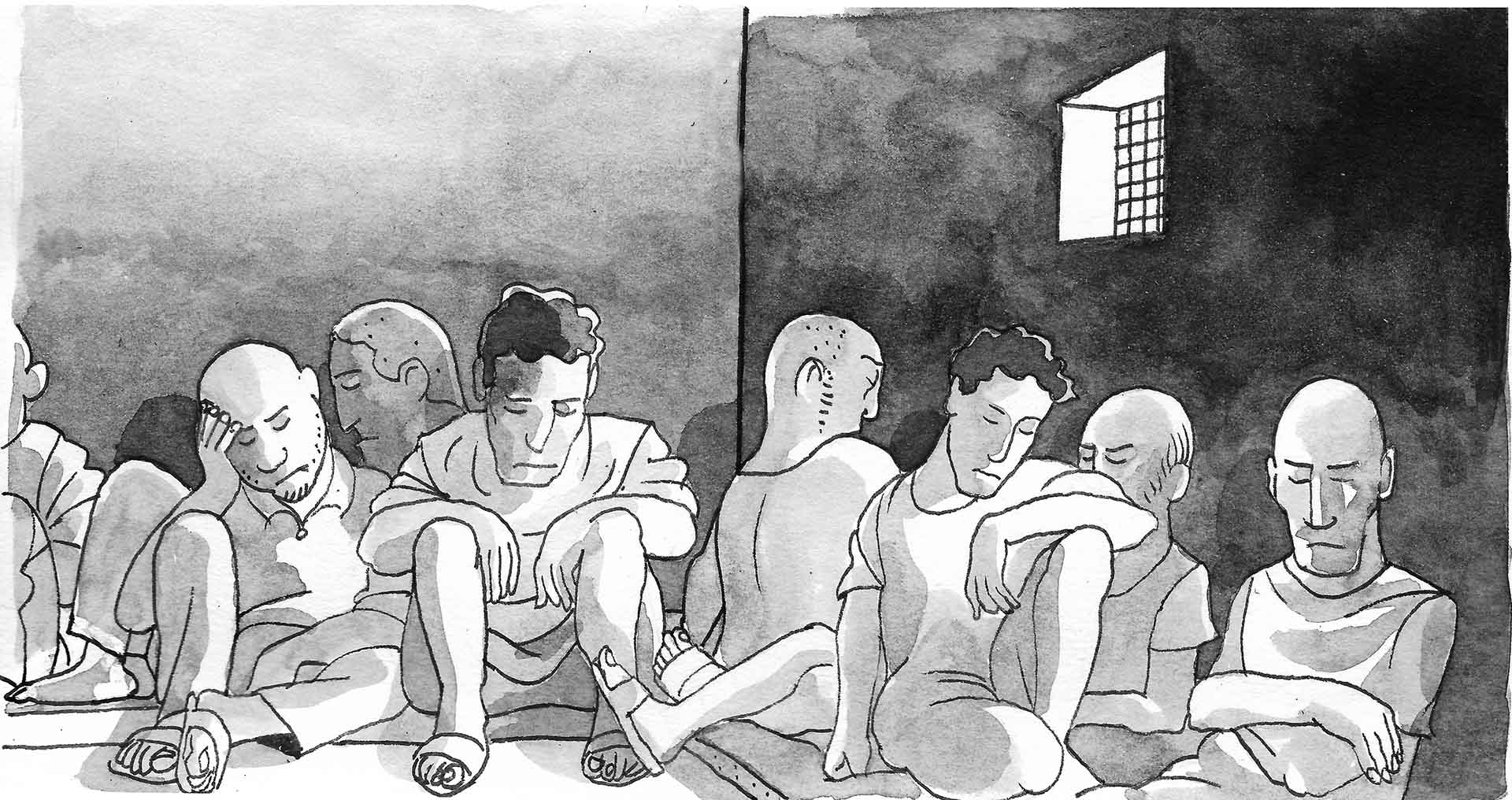

Overcrowded prisons

You could get to experience the delightful interior of a Tunisian prison for a variety of reasons: petty theft under civil law, cannabis consumption, a bounced cheque, defamation, adultery, alleged homosexual relations etc. The repercussions are clear: overcrowded prisons that are incapable of appropriate supervision, and affinity between ordinary prisoners and those accused of terrorism, with no measures for separating the two. Badreddine Rajhi has witnessed the pressure on prisons building up since 2011.

"In addition to this pressure, we are faced with prisoners who present a danger. We can't treat them like others; we need higher security, more vigilance and greater resources."

Badreddine Rajhi is Secretary General of the Prisons Union.

As a result, this overcrowdedness can function as a potential breeding ground for future (jihadi) recruits. " The number of recruitment centres is multiplying", says Moez Ali, president of the Union of Independent Tunisians for Freedom (UTIL), an association that works with the prevention of violent extremism and that provides support for families. " You enter for smoking a joint, and you exit as a terrorist.” Welcome to the school of re-offenders and radicalisation…

For over two decades, Tunisian prisons have functioned as the ideal locations for schools that foster future jihadis. Even though this phenomenon of young and troubled men being taken under the guiding wings of former combatants from Afghanistan and Iraq during the long years of detention has been an issue since the early 2000s, there is no indication that the issue is currently being taken more seriously.

Despite there having been talks of a high-security prison specifically for 'radicalised' persons, it has not seen the light of day due to the high risks associated with the security of the facility itself. Hence, the overcrowded and unhealthy detention centres remain ideal incubators for proselytising, which is particularly effective on psychologically fragile detainees who are especially receptive to the lures of violent extremism.

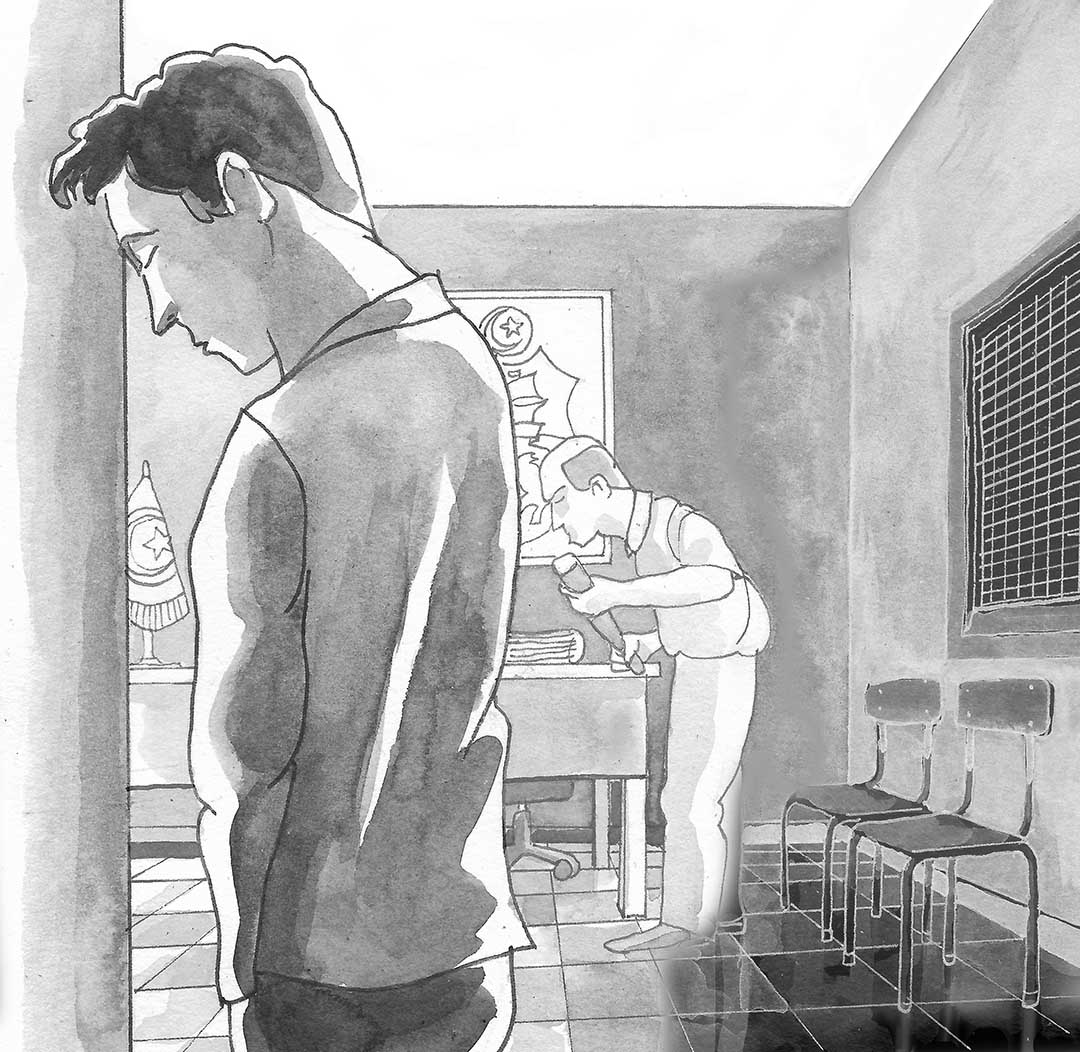

The machinery for breaking down and radicalising first-time offenders* is already in place prior to imprisonment, even as soon as they are arrested and held in custody at detention centres. Not all defendants are dangerous criminals - far from it - and they remain innocent until proven guilty. However, there are numerous testimonies and accounts of the brutal and inappropriate behaviour of law enforcement officials from the moment of arrest.

Police Violence

Those arrested in cases related to terrorism are all the more familiar with this 'preferential treatment' i.e. the brutal arrests, torture and systematic incarceration in degrading conditions regardless of the severity of the offence. This security policy was made possible by a state decree of emergency, which has been enforced since 1978* and entails a set of practices that paradoxically foster what they are supposed to restrain: the growing danger of violent radicalisation.

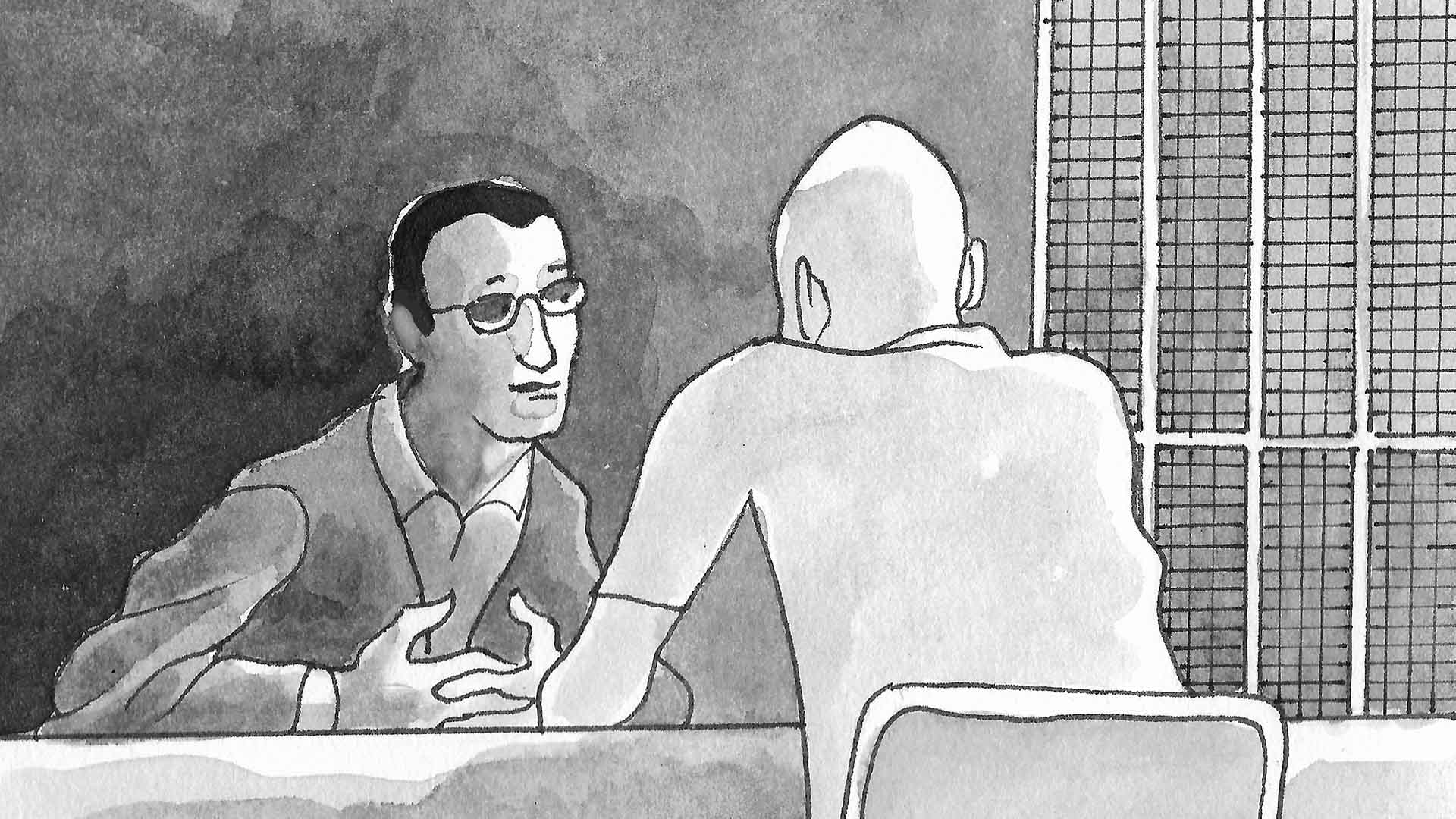

Rim Ben Ismail is one of the few psychologists who works with detainees incarcerated for terrorism. She has also been involved in handling former detainees of Guantanamo Bay, and has witnessed the perverse psychological effects of such practices first hand.

"The level of dehumanisation that law enforcement officers enforce or seek to achieve really humiliates people by forcing them into a primitive state."

Rim Ben Ismail is one of the few psychologists working in prison with detainees involved in cases related to terrorism.

Many NGOs and lawyers also criticise the indiscriminate pre-trial detention of relatives, family and friends for up to 14 months or more. What is perhaps even more controversial is investigating judges sentencing detainees through hasty investigations in which the evidence obtained is limited to confessions under torture.

Sometimes, even oftentimes, people who have no knowledge of the crimes that they are accused of are incarcerated. In this regard, the testimony of B. (accused in the trial concerning the Bardo-Sousse attacks* [see episode 1]), seems significant. The man: a socially integrated citizen with no criminal record, was together with his wife thrown into the hellish spiral of antiterrorist justice after his brother was found to be an accomplice in the Sousse attack. B. was accused of having concealed a telephone.

"During the days when my wife and I were there, they would bring my brother in, beat him and undress him, before bringing us in."

B. was one of the defendants in the trial for the Bardo-Sousse attacks.

B. was ultimately sentenced to 3 months in prison... but only after having spent 13 months in detention awaiting trial.

Psychological trauma

In this testimony, as in many others, it seems that the judicial authorities are not respecting the concept of ‘innocent until proven guilty’. Off the record, a Tunisian prosecutor in charge of cases related to terrorism (who has since been transferred), admitted with confidence that for him there was no such concept, there were only guilty persons.

It is difficult not to connect this type of practice to the sense of injustice that persists for many detainees, long after their arrest and incarceration. This leads us to the following question: can the treatment they receive (which is seen as arbitrary), and the detention that is perceived as unjust, radicalise the individual vis-à-vis the State? A few techniques can be used to address this question.

According to a study by the ITES, 90% of imprisoned ex-Jihadis express a desire for revenge against a Tunisian state that they consider to be unjust. While these figures should be taken with a grain of salt, they confirm the sentiment of the psychologist Rim Ben Ismail.

"The after-effects of torture and ill-treatment leave a very strong and significant legacy of inner violence."

Rim Ben Ismail is one of the few psychologists working in prison with detainees involved in cases related to terrorism.

Imen Triki, one of the leading lawyers for Tunisian jihadis, shares this view, as do many of her colleagues.

"The jihadis who chose to join the ranks of Daech were, in the majority of cases, victims of harassment, torture, ill-treatment and humiliation inside Tunisian prisons."

Imen Triki is one of the leading lawyers in Tunisia for jihadists and their families. A human rights activist, she was also president of the association of Liberty and Equity between 2011 and 2014.

Therefore, it is not the function of the prison as a place of detention that needs to be examined, nor is it the sentences served as punishment for crimes committed. It is rather that the fact that the attitude of the authorities reinforces the feeling that the prisoners are dispossessed of their dignity, and that they are subjected to arbitrary treatment that they are powerless to control.

"They find it difficult to feel emotions like they used to; they speak of death or mourning that they could not register, when they were not able not cry, where they could not express any form of emotion."

Rim Ben Ismail is one of the few psychologists working in prison with detainees involved in cases related to terrorism.

The organisation ‘ Reprieve’, for which Rim Ben Ismail worked (and which has analysed the practice of torture made legal by default), was founded by Clive Stafford Smith in 1999 to provide free legal defence to those who cannot afford it. The organisation has made it possible for as many as 300 people who were sentenced to death in the United States to assert their innocence and to escape death row. Representatives then filed a lawsuit against the US federal government to compel it to allow lawyers to defend the prisoners held in legal limbo at Guantanamo Bay.

“He asked: ‘Which one would you choose? Would you prefer a razor blade to your genitals or [constant] deafening music?’ Most people say that they would rather go with the deafening music, but he said: ‘No, that’s the wrong choice! Because if you choose physical torture, you know that there is a beginning and an end’.”

Clive Stafford Smith is a lawyer, founder of ' Reprieve', who has been active in the fight against the death penalty in the United States and in drafting the defence for Saddam Hussein. He is currently a lawyer for ex-jihadists imprisoned in Rojava. In January 2019, with the help of Roger Waters (founder of the rock band Pink Floyd), he had two British orphans repatriated by private plane without permission, marking the debate on returnees in Britain.

Rim Ben Ismail compares the torture mechanisms at Guantanamo Bay with those used in Tunisia, and discusses the subsequent mental health issues that she has observed.

"Some people proclaim: ‘I have become a machine!’ So you’re trying to work with someone who no longer feels human, but rather like a machine."

Rim Ben Ismail is one of the few psychologists working in prison with detainees involved in cases related to terrorism.

Mistreatment amounting to torture (despite being explicitly condemned in the new Constitution* and less systematic since the Revolution), is still used as an investigation method by security forces, and as a punitive response by the state thereafter. While it is legally possible to lodge a complaint against the perpetrators of such mistreatment, there have been no successful proceedings to date, as confirmed by lawyer Bassem Trifi, the vice-president of the Tunisian League for Human Rights (LTDH).

"This culture could not be completely erased after the revolution. It still persists in the Ministry of the Interior, within the police officers who handle interrogations."

Bassem Trifi is a lawyer, and Vice-President of the Tunisian League for Human Rights (LTDH)

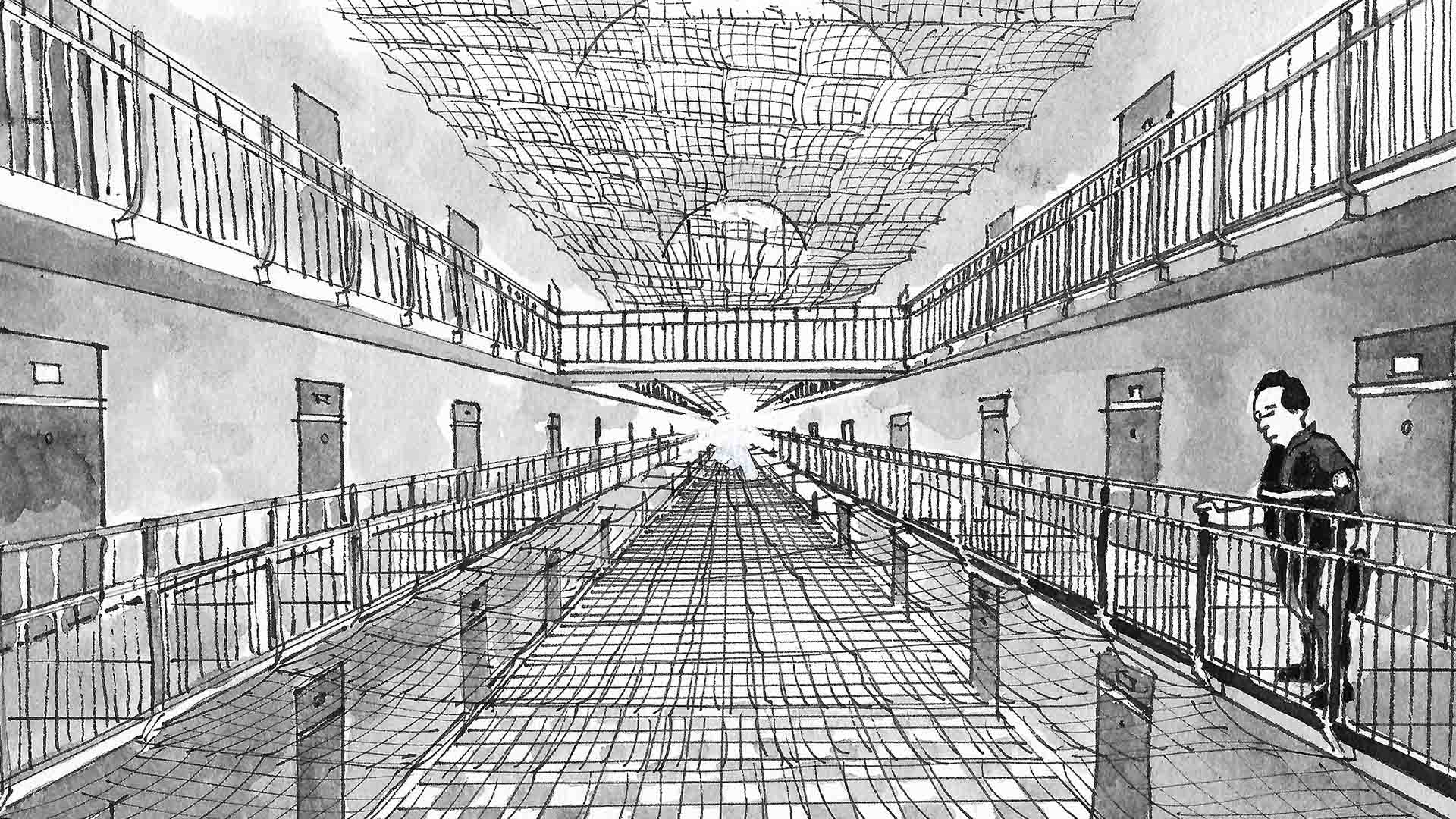

As recommended in the report submitted to the National Security Council in August 2015, a key to preventing violent radicalisation in prisons is the implementation of a rehabilitation programme for those accused and convicted of terrorism.

It should be possible to use the length of the prison sentence to rehabilitate the individual. However, as Mokhtar Ben Nasr points out, if Tunisia were to invest significantly in the reintegration of prisoners charged with terrorism, and curbing the spread of violent extremism, why should it do so only for this category of offences? According to Ben Nasr, prisoners would then ask themselves: " Do I have to become a terrorist for the state to take care of me?"

"If (in order to rehabilitate someone who was a terrorist and most likely killed someone), we provide them with a plan, then what will we offer a 'common' thief or criminal when leaving prison?"

Mokhtar Ben Nasr is the former spokesman for the Ministry of Defence, Head of the Tunisian Centre for Global Security in 2014, and of the Commission for the Fight against Terrorism in 2018-2019.

Moreover, this means that the justice system must effectively examine the nature of the detention, as well as the background of the detainees, i.e. questioning the very notion of extremism, the level of danger that the detainees pose, the consequences of their detention (both for themselves, as well as for other prisoners), and possible rehabilitation programmes.

Since 2015, various reports have successively redefined these concepts in Europe, moving away from the notion of deradicalisation to that of de-indoctrination, leading to disengagement (or de-enrolment). The term de-radicalisation was quickly abandoned, as the incarcerated person could be intellectually radicalised without posing any sort of danger. Indoctrination is not in itself a threat, nor a systematic transition to violence.

Today, the term ' disengagement' is the preferred term; interpreted as ‘disengagement from violence’. It is not a question of the condemned person renouncing his or her personal ideological framework, but rather the use of violence. Based in Montreal, Hicham Tiflati studied the different roots of radicalisation, based on direct interviews with Daech members.

"When you 'legalise' racism, it also has an effect on minorities and other minority groups within society."

Hicham Tiflati is a former research associate at the Centre for the Prevention of Radicalisation Leading to Violence in Quebec, Canada.

A Radicalisation Machine

What form of detention should be envisaged for those imprisoned for terrorism? The question is more urgent in Tunisia than elsewhere, as detainees for terrorism account for almost a tenth of the prison population (compared to about 1% in Europe). These prisoners meet, exchange ideas and organise themselves. In short, they collectively become more dangerous. If they are detained in close contact with other prisoners, as previously mentioned, there is a real danger of proselytising, an issue that for example French prisons faced in 2014.

The above mentioned phenomenon occurred in Fresnes prison, the second largest prison in France, and the primary incubator of radicalised prisoners. The director, faced with the delayed action of his supervising ministry, and witnessing active proselytising throughout his facility, decided to place radicalised prisoners in solitary confinement, where the conditions were deplorable due to lack of resources. This forced the general management to react. The response of the French Ministry of Justice came a few months later with the creation of their first specialised section, later renamed the Radicalisation Evaluation Quarter (QER).

The QERs mandate is to divide the prisoners for terrorism into three main categories. The first category deals with those who entered IS 'by mistake', i.e. petty criminals, individuals with ‘follower personalities’ or who are going through an existential crisis, etc. These categories represent about 80% of prisoners charged with terrorism. After being assessed over several months, the first group can then return to ordinary detention with other prisoners. The remaining 20% are then divided into two categories: one which is held in QIs (Isolation Quarters), and the other in QPRs (Quarters for the Prevention of Radicalism).

About half of this 20% are considered to be ideologues with deep-rooted convictions, and proselytisers. Hence, their detention cannot take place together with ordinary prisoners. The French prison administration believes that ideologues cannot merely be 'de-indoctrinated', which is a long and uncertain process. Instead, the goal is for them to renounce the use of violence as a means of reaching their goal. The programmes are only successful for a small part of this prisoner category. The remaining 10% are even more complex, as they are the ones qualified as 'ultra-violent', and whose aim is more akin to a search for violence in itself.

In Tunisia, the categories for terrorism detainees are roughly equivalent to France’s. According to Moez Ali (president of UTIL), the profiles of the detainees with whom his association has been able to work, categorise around 80% of prisoners as belonging to 'social difficulty', and 20% as ideologues. Considering this similarity, could the methods experimented with in France and elsewhere also be useful for the Tunisian justice system? This question remains unanswered for the time being. While waiting for clear direction, prison staff find themselves having to play the role of social mediators, finding their own solutions.

"Do we burn them, throw them out? Let's be pragmatic; after all, they are human beings. Since we have to deal with them, our duty is to get them back on the right track."

Badreddine Rajhi is Secretary General of the Prisons Union.

These programmes are long overdue, and furthermore, Rim Ben Ismail advocates for greater consultation with civil society in the field of prevention.

"There is a non-security dimension within the prevention of 'violent extremism' (which is now a buzzword). However, this is in response to requests from donors and certain organisations, and I’m not sure if the state is really convinced of this."

Rim Ben Ismail is one of the few psychologists working in prison with detainees involved in cases related to terrorism.

Effective security management of violent extremism in the short term will not allow Tunisia to avoid a longer-term programme to curb the "radicalisation machine". This reflection is not limited to referring to the incarceration period itself, but also extends to what many prisoners and their lawyers condemn after their release: a life that effectively functions an open-air prison.