In 2011, as the country was in a state of revolt, the inhabitants of Borj Essalhi (the ‘Salhaoui’) simultaneously rose up against STEG in protest of the construction of the first Tunisian wind farm just outside their village ten years earlier. "We demand the removal of the wind turbines that are closest to the village and built on our ancestral farmland during Ben Ali. Since the revolution, we have stopped paying our electricity bills to STEG in order to make our claims heard", says Hammadi, a farmer and resident of Borj Essalhi.

Power cuts in the village have increased since the residents began refusing to pay their bills in protest. Whilst the debt to STEG increases with every day (currently at around 300,000 dinars according to Mounir Ghabry, the director of citizen relations at STEG), the residents are blaming the incessant blackouts on the electricity company and their lack of electrical network maintenance. STEG denies these accusations, and according to Ghabry "the residents refused to let [their] workers enter the village, who were [therefore] unable to do their job".

Borj Essalhi is in the middle of a paradox: while the energy produced by the wind that passes through this small town provides electricity to 50,000 Tunisians, the Salhaoui themselves have to resort to using candles several times a year.

A view of Borj Essalhi. The wind turbines from the third installation project in 2007 bordering this small Cap Bon village.

TEN YEARS OF STRUGGLE

Samir Salhi, a 55 year-old livestock farmer and fisherman (whose ancestors maintained the same profession for generations in this village, nestled between the mountain and the sea), remembers the day when government officials came to photograph his land, which is situated at the top of the village. This was in 2007, and Samir was offered no explanations. A few months later, workers began to construct two wind turbines right in front of his childhood home, where he used to graze his sheep. Since then, Samir has suffered the consequences of these facilities depriving him (as well as many others) of important farmland, restricting farming activities, which in Samir’s case reduces his only source of income.

"We used to grow wheat, corn [and] tomatoes. Before the arrival of the wind turbines, our land was very valuable, but today it is worth nothing", says Samir.

Hanging on the wall, his low-voltage meter has not been changed for the past 20 years. "We have a wind turbine planted in the garden but I can't have two household appliances on at the same time! I need additional electricity for irrigation and other appliances, but there is none", says Samir. According to him, STEG has refused to replace the meter, or to improve the network since the protests began.

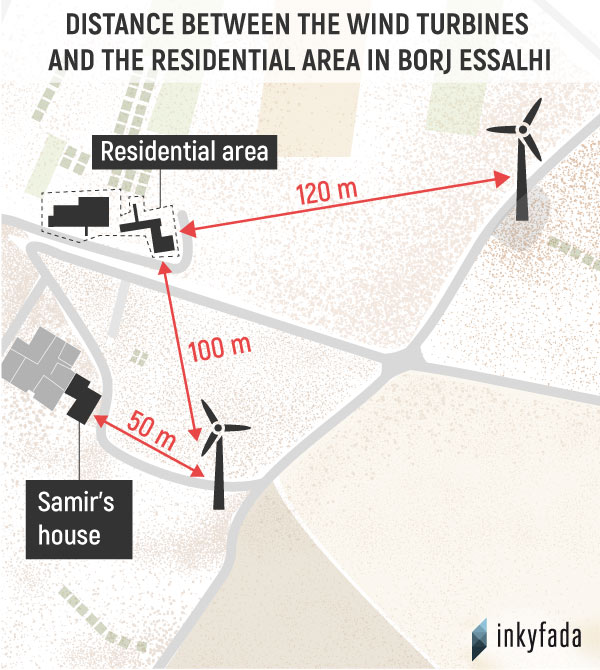

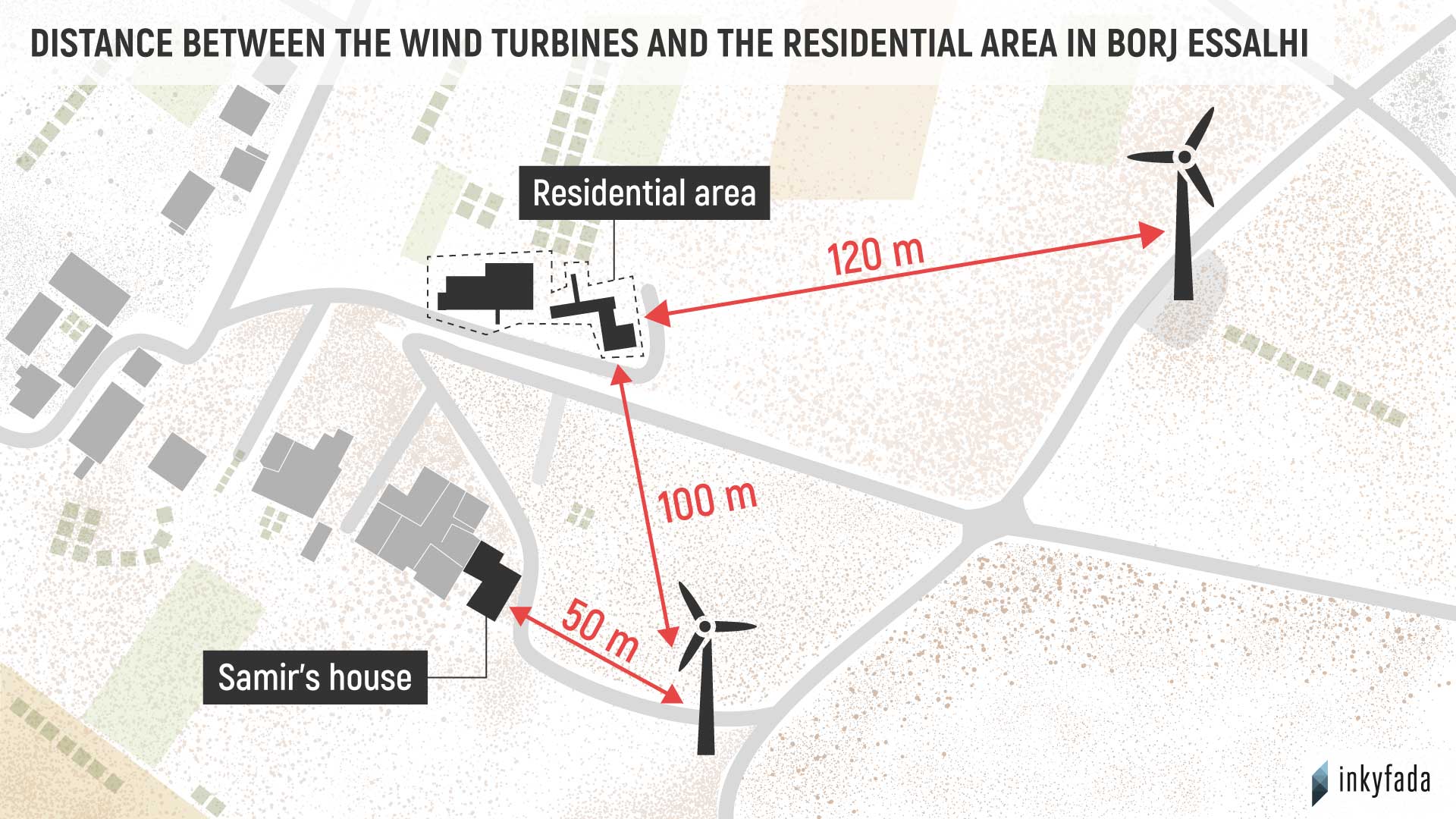

Samir's family has had a wind turbine 40 meters from their house since 2007.

The village has been struggling for the past ten years. To demand the return of their electricity, the 147 families of Borj Essalhi regularly block the roads and organise sit-ins by the offices of the STEG power plant during blackouts. "In September 2018, we stayed in front of STEG for 18 days straight, engulfed by darkness during the entire time. The whole village was there, children and women as well. We slept and ate there. No one from STEG showed up", says Najeh, one of the co-organisers of the protest. In order to get their electricity back, the residents have to either appeal to civil society associations or MPs. "Samia Abbou, an ARP member, met us with a small delegation. They talked about it in the Parliament and, just as magic, the electricity came back."

"STEG would leave us for months without electricity. They come to cut the power at night so that no one sees them. At the village entrance there is a generator that can cut the whole village off from the network", explains Hammadi. When contacted by Inkyfada, STEG denies any involvement in the power cuts, claining that they occur from natural causes, and accuses the residents of manipulating their meters in order not have to pay their bills.

"WE GAVE UP OUR LAND FOR A PITTANCE"

The desire to diversify Tunisia's energy resources is the root of this wind power plant project. "Tunisia is a country that is very low on fossil fuels, so the objective was to seek alternative energy sources. Sidi Daoud is the first wind farm in Tunisia", says Hassane Mouri, an environmental sociology researcher. According to the environmental impact assessment conducted in 2009 for the third phase of the Borj Essalhi project, the national demand for electricity continues to increase at an annual rate of nearly 5%.*

To meet this growing need, STEG already set its sights on Borj Essalhi in the late 1990s. "There is a lot of wind here, that's why they chose our village", says Hammadi, another farmer and fisherman from Salhaoui. "We used to farm here before. Then in 2000, we had no choice, we had to forfeit some of our land", he recalls.

"We were promised clean energy, but the consequences have been terrible for us", Hammadi says indignantly.

Bit by bit, the agricultural lands bordering the village are leased to STEG and the wheat fields give way to the wind turbines. "At the time we did not know how to negotiate. We gave our land up for a pittance, and today we can no longer go back", Hammadi regrets. According to a rental contract that Inkyfada was privy to, a piece of land was rented to STEG for thirty years at about 1300 dinars, meaning 43 dinars per year, and renewable. "Some rented [their land] out for less than 300 dinars. At the time of Ben Ali, we could not refuse. We were dispossessed by force", he adds.

In 2011, as the revolutionary fervor spread across the country, farmer Jomaa Salhi demanded the right to regain control of his land, which had been inherited from his father, for farming purposes. However, there was an issue: these lands, rented out during the first phase of the wind farm construction, now belong to the State, and are registered under the authority of the Department of Forestry. "They started planting trees around the wind turbines so that we could no longer access them. Now a lot of our land is classified as forest, and the majority of the forests belong to the state. How can we get them back?"

A SERIES OF NUISANCES

With his measuring tape at the ready, Samir measures the distance between the nearest wind turbine and his home; barely forty meters. "This wind turbine is 70 meters high, even 90 meters if we count the blades. I pray that it will not fall on our heads!" In the absence of any national regulation on the minimum distance between a wind turbine and a house, the international recommendations suggest a minimum distance of 500 meters to avoid nuisance to local residents. This is because, according to a study by the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety, "it is difficult to hear the noise from a wind turbine from a distance of over 500 meters."

Samir is nevertheless afraid of the wind turbines collapsing on his house since they have already collapsed three times on the Sidi Daoud wind farm. "It is [partly] due to the wind, but mainly because STEG is making savings. The first wind turbines that were installed in 2000 have started to rust", says Najeh, who worked on the electrical maintenance of the site for six months. The equipment for the wind power plant was financed with concessional funds from the Spanish government, but the maintenance costs fall under the responsibility of STEG who are responsible for the project.

The first wind turbines that were installed on the site in 2000, rusting.

"It's been four years since this wind turbine fell, and no one from STEG has taken care of the waste since then", Najeh continues as he walks along the remnants of the wind turbine. According to Hassane Mouri, who is currently conducting a study on the social impact of these wind turbines: "This waste is harmful; it contains electronic parts and batteries with heavy metals. It is very dangerous for the water table."

Waste from the wind turbine that fell four years ago.

In addition to this immediate danger, the residents have experienced a series of nuisances since the installation of a wind farm near their homes. "My wife gets very stressed because of the noise; it never goes away. Sometimes it is so loud that we are unable to sleep at night" Samir continues, grasping a medical certificate proving the deteriorating health of his wife, who suffers from serious issues with blood pressure.

In addition to the risk of hearing loss and deafness, the potential impacts of noise on health are numerous, including an impairment of the immune system, chronic sleep disorders or an increase in heart rate, according to the abovementioned study by the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety (AFSET). It should be noted, however, that not all studies are in agreement on this point.

A NOT-SO-GREEN ENERGY

Like all the other farmers in the village, Habib is now forced to graze his flocks by navigating between the wind masts: "Wind turbines do not only affect human beings, but also our animals. They get afraid when there is a lot of noise", he explains while observing his sheep from afar. "The sound of the turbine brakes particularly disturbs the animals; the cows are alarmed and run away when they hear it", he continues.

According to Hassane Mouri, researcher in environmental sociology and leader of a social impact study on the implementation of wind turbines, the development of access roads for the maintenance of wind turbines has also seriously impacted farmers in the region. "The tracks have turned into ravines and flooded the fields. The land has become unusable due to these discharges", he says.

The wind farm also has a negative impact on the migratory birds that pass through Cap Bon in the spring, as the area is one of the main migratory routes in Africa. The birds sometimes hit the blades and are found on the ground by locals. "Before, the birds used to pass through our area, now they avoid it", Samir explains. He is also concerned about the toxic effects of the resins used to maintain the wind turbines. The chemical residues of the lubricating oils used to make the blades turn with ease, affect the quality of the soil. "I often find this substance spilled in my field, not far from my home. STEG does not maintain the wind turbines properly."

Farmer Samir Salhi, observes the family land that he had to rent to STEG, now housing the wind turbines.

For the inhabitants of Borj Essalhi, the landscape has lost its value. There is a bitter sense that "this corner of paradise has changed its face in 20 years. It has been devalued", says Najeh Salhi. Instead of focusing on local heritage to highlight the tourism potential of the region, the state decided to install the country’s first wind farm in Borj Essalhi; a decision that 20 years on, has proven to have had harmful consequences. Financed in part by the World Bank and other international institutions as part of a program for the development of renewable energy, the wind farm was installed in this location because of its "distance from urban areas" (as noted in the impact study published by STEG in 2009), without taking the actual presence of a few hundred people in the area into account.

"By wanting to have projects everywhere, they killed everything here. Renewable energy, but for whom? We don't benefit from the wind turbines, because the electricity produced is not even for us. They cut us off when we express our anger. We sold our lands, and the ones that remain do not generate good harvests", Hammadi sums up, denouncing the inaction of the State.

Ten years after the first protests by the inhabitants, STEG finally decided to address the issue. "We met with the residents and we are ready to assume our full responsibility and to end this ten year conflict", says Mounir Ghabry, director of citizen relations at STEG. Among the recent promises made by STEG are inspections and upgrades of the electricity network, cleaing up the remnants of the fallen turbines, as well as transparency regarding the land contracts that were previously signed. "Nothing has happened since March 4; no one has come. I don't believe in their promises anymore", Najeh said.