"The condition was that these individuals had to be under strict control, and that justice had to prevail."

Mokhtar Ben Nasr, former spokesman for the Ministry of Defence. He was the head of the Tunisian Centre for Global Security in 2014 and of the Commission for the Fight against Terrorism in 2018-2019.

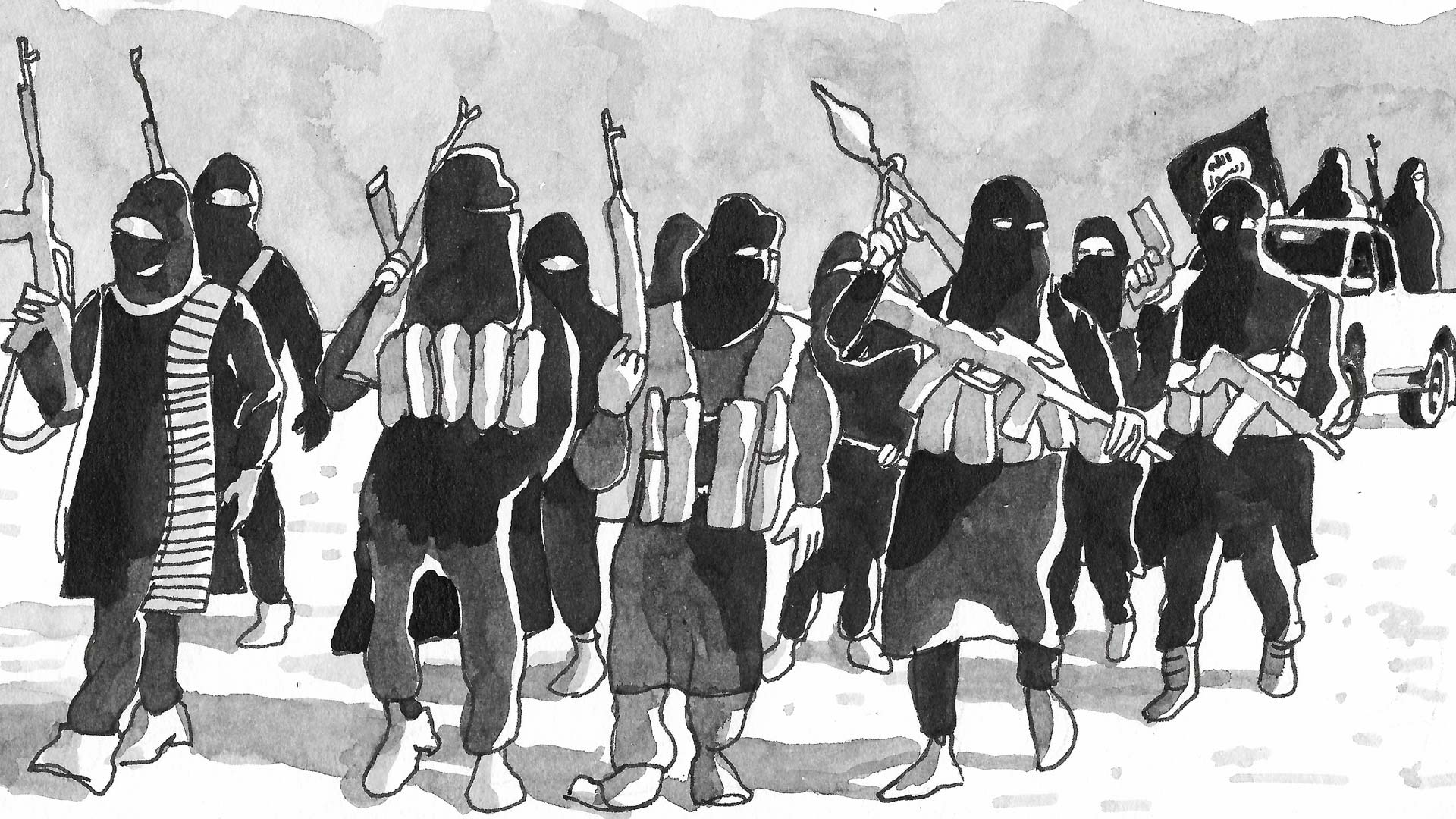

the fall of the islamic state

Since 2017, following a series of military defeats and the fall of its last militarised enclave at Baghouz in Eastern Syria in March 2019, the Islamic state (IS) had lost all of their territories claimed since 2013, at the cost of many lives. The coalition of Western powers announces a bombing victory over " the most important terrorist organisation of all time"; a decisive - albeit probably short-lived - victory over the combatant organisation.

International media decends on Baghouz to film the devastation of the martyred city covered in dust and sand, from which long lines of ragged (and often wounded) fighters, dirty children and a swarm of women in black (turned grey from dust) niqabs are trying to escape. In the hours and days that follow (as was the case in Raqqa and elsewhere), American, folllowed by French intelligence officers " debrief" fighters that are deemed to be sources of valuable information.

This information is indeed a rare commodity. Since 2014, the coalition's military offensive had not bothered to collect evidence or testimonies. As many lawyers and prosecutors have acknowledged, the military offensive has not been accompanied by the appropriate investigations necessary to hold fair trials for ex-jihadis. Victims are not identified, and the identities of the perpetrators of war crimes are either unknown or limited to sketchy records as sources. Moreover, there is almost no reliable information on all of the women of Daech, who are known to have actively supported the war crimes committed by IS.

How can ex-jihadis be prosecuted under these conditions? For their undifferentiated participation in a terrorist organisation? For violating a number of international regulations? Or perhaps individually, based on almost non-existent evidence? And should these prosecutions be handled on the spot, in the countries where the crimes were committed - or in the perpetrator’s country of origin?

The debate here is not a matter of opinion; it is a dilemma that goes right to the heart of the justice system, to the laws of armed conflict as defined by the Geneva Conventions, to their functioning and their ethos. It is within this context that the courts must now face the challenge of dealing with ex-combatants and their families.

It is understandable that in the face of such uncertainties, the political authorities of a country will not be in a hurry to bring back returnees, be it men, women, or children. Given the large scale of the phenomenon locally, Tunisia cannot escape this dilemma. Supporters of the rule of law can rejoice in the fact that the Tunisian justice system has not followed in the footsteps of countries such as Egypt or Iraq, who have not hesitated to hand down death sentences through unfair trials. So how can we reconcile human rights and respect for international conventions with security concerns?

thousands of returnees?

A seemingly simple, yet tricky, question can reveal the complexity of the phenomenon we are faced with: how many Tunisian ex-jihadists have left to fight in foreign conflict zones? The answer to this question depends on a range of conditions and assumptions. In 2014, the UN initially estimated the number of fighters who left to fight in the conflict zones in Libya, Iraq and Syria to be between 6,000 and 7,000, placing Tunisia at the top of the list of countries supplying foreign fighters to IS.*

This number was an initial estimate and included Tunisians who were already in Syria before the beginning of the conflict, many of whom were not involved in warfare.

Meanwhile, Tunisia reports the official number of Tunisian foreign fighters in IS to be 2929*, without specifying the exact method used for this calculation.

This number seems to be an underestimation as it only includes identified departures, and excludes Tunisian fighters who left for Syria with a false passport, particularly Libyan ones, as well as those who left illegally without passing through official border crossings. The number also does not take into account those who may have changed their identity - a frequent practice among IS fighters.

Due to this, it is virtually impossible to present an exact number. However, somewhere between 4,000 to 5,000 Tunisian combatants seems to be a plausible estimate. According to an estimate made by the Tunisian judiciary, confirming previous American and Russian reports: a significant proportion of the fighters (about 1100) died in conflict zones.

Consequently, it would be very difficult to provide an exact number of potential returnees. Several hundred? Several thousand? This is primarily because the majority of the jihadi fighters who are not killed on the spot tend to be redeployed rather than return. Nearly 2000 Tunisian jihadis and ex-jihadis may still be alive, and many of those who have not been captured in Syria are moving to other conflict zones, ranging from Libya to the Congo.

"These people have other tasks now; they have been brainwashed and turned into real mercenaries who could easily switch sides and go and fight elsewhere."

Mokhtar Ben Nasr, former spokesman for the Ministry of Defence. He was the head of the Tunisian Centre for Global Security in 2014 and of the Commission for the Fight against Terrorism in 2018-2019.

According to reports by foreign security sources, there are around 1000 surviving combatants who are still active in Libya. This is a plausible number if we take into account the several hundred Tunisian prisoners, 500 of whom are recognised and have been listed by the Tunisian Observatory for Human Rights (OTDH) according to family declarations.

"More than 75% of them come from marginalised regions, especially from the central or border areas, and are in a difficult economic situation."

Mustafa Abdelkebir, activist from Ben Guerdane, president of the Tunisian Observatory for Human Rights (OTDH), based in Medenine.

Also in Libya, security reports point to the reappearance of several Tunisian jihadis (formerly active in the Syrian conflict), redeployed as paid mercenaries on both sides of the Libyan conflict. They are mainly being brought by the Turkish forces siding with President-elect Fayez Al-Sarraj, but also on the side of General Khalifa Haftar, to whom their experience on the ground is financially valuable.

The detention situation also remains unclear. Bashar Al-Assad’s regime officially detained the 41 Tunisians who were captured crossing the Syrian-Turkish border in 2013 (including a former member of the so-called Soliman group).* No other number of detainees has been reported.

On the other side of the border, the Iraqi authorities detain only a small number of Tunisians: a tiny minority having fought on Iraqi soil (1.5% of departures). Since most of them have been killed since, there are officially only 15 Tunisians in detention, 6 of whom are currently on death row in Iraq.

Turkey, however, has facilitated a greater number of Tunisian ex-jihadist returns, due to the increased security cooperation between the two countries since 2018. It is speculated that there are about 300 Tunisians detained in Turkey. Despite this being plausible, the number is rejected by the Turkish ambassador to Tunisia.

The majority of potential Tunisian ex-combatants, however, are identified and detained by Syrian Kurdish forces in Rojava. As of 2019, former members of Daech and their families await their fate in makeshift camps, such as El-Hol for women and children, and prisons such as Qeshmili for men.

On the same subject

negotiating returns

For the Kurdish authorities in Rojava, these foreign ex-combatants, although burdensome, constitute a precious spoils of war that could prove useful; they represent both a dilemma and a political opportunity. Initially, the Kurdish authorities sought to engage in direct dialogue with the countries of origin, paving the way for diplomatic recognition. Most of the countries approached closed the door to such dialogue. In addition, in the hopes of a rapid withdrawal of their troops, the American authorities began to put pressure on the countries of origin, but to no avail.

Faced with this lack of progress, the Kurdish authorities proposed to put the ex-jihadis on trial in Rojava, a potentially lucrative and politically rewarding undertaking, which, all in all, seemed to make sense; numerous atrocities were committed on territories that are now under their control.

Yet, the regional geopolitical stakes decided otherwise. The Ankara government's bombing of the autonomous Syrian province of Rojava at the end of 2019, targeting prison camps in particular, complicated the situation and put an end to the (albeit weak) negotiations that were under way. Although the Kurdish authorities were able to anticipate the strikes and move some of their prisoners, some still escaped or managed to pay for their release, a widespread yet rare practice amongst prisoners.

Tunisian authorities estimated the number of official returnees between 2011 to 2017 to be around 800. However, it should be noted that not all of them are ex-combatants, and since then, there are reports of 200 to 300 additional returnees.

"We were awaiting decisions regarding the return of these fighters, and expecting an increase in the number of trials, either as the result of simply returning or extraditing fighters of Tunisian nationality."

Judge X is one of the judges appointed to the Antiterrorist Pole of Tunis. For security reasons he requires to remain anonymous.

The methods of returnee management are a matter for the Tunisian justice system, and in turn depend on the number of potential returnees. Tunisia is not immune to international dilly-dallying on this matter. There is also no question that judges in certain places are, as previously mentioned, handing down death sentences based on virtually empty case files or case files filled with confessions obtained under duress. This method of death sentences subsequently hinders international judicial cooperation on a subject that is already controversial.

"When France would request Tunisia to carry out criminal proceedings, to conduct investigations, to interview witnesses, or to search premises, Tunisia would do it. And when Tunisia, within the same context, would ask France to interview witnesses, to carry out searches and investigations, France would not comply."

Philippe Dorcet, former examining magistrate, turned president of the Court of Cassation in Nice. Currently the French liaison magistrate at the French Embassy in Tunisia.

a justice system in turmoil

The Tunisian justice system is in an uncomfortable situation. Without the necessary initiative, it finds itself dependent on prerogatives in politics and security. Constitutionally, Tunisia cannot refuse foreign fighters to return.* However, the problem is that Tunisia also cannot request their return, i.e. they can neither launch nor approve any return procedure. Therefore it is up to the ex-jihadists, their families and their lawyers to manage each return individually, with all the administrative obstacles that this entails.

The same situation goes for the women and children of IS, as the women often refuse to be separated from their children and continue to be " forgotten" by the Tunisian authorities.

"There are lots of children in Libya, in Mitiga prison and probably elsewhere. The Tunisian authorities have so far failed to, or simply lack the political will, to retrieve them."

Anouar Ouled Ali is one of the main defence lawyers of jihadists and their families in Tunisia. He also heads the association “Observatory of Rights and Freedoms” in Tunisia.

This status quo is partly explained by inadequate support systems. For example, the centres dedicated to juvenile delinquency are not prepared to receive the "lion cubs of the Caliphate". There are effectively no suitable systems set up to take care of children, other than their mothers. This is problematic since it is difficult for the justice system to know whether these women pose any danger or not.

Should the children be placed in foster care, in the custody of their grandparents? While this possibility is being considered, the authorities have be able to ensure that there is no " ideological" continuity. In February 2019, this was the subject of a heated debate between the lawyer Anouar Ouled Ali and the ARP member, lawyer and feminist activist Bochra Bel Haj Hamida - a debate which took place in the Family and Social Affairs Committee of the Assembly of the Representatives of the People (ARP), the responsible committee for deciding the fate of the returnees and their families.*

Subsequently, a decision was made by the Security Council at the end of 2019: only a few, particular ex-jihadists and orphans would be repatriated. Tunisia would not help to facilitate any returns for the rest.

The controversy in judicial circles is based on the fact that the question of proof continues to be point of concern. What was the war zone function of the defendant in question? Was he or she an assistant or a chief beheader? Or perhaps a propaganda officer, or a fighter responsible for countless war crimes? These are very difficult questions to answer.

What is an appropriate punishment? The problem here lies in the origins of the indictment, which itself depends on intelligence information, often sourced by foreign countries.* But under what circumstances was this information gathered? An intelligence information file is not an investigation file, it is a collection of accumulated information from anonymous sources, gathered in uncertain and above all confidential circumstances. The prosecution is obliged to provide verified sources for the trial, obtained in a context of legal and transparent examination. So in the absence of other evidence, how can an ex-jihadist be charged on the basis of mere intelligence notes that are rendered invalid in court?

"In some cases, these individuals contact their families via telephone or Skype. In most cases, they don't reveal that they are fighting. They say where they are, that they are alive and that's it. However, this point of contact can be a good lead for finding evidence."

Judge X is one of the judges appointed to the Antiterrorist Pole of Tunis. For security reasons he requires to remain anonymous.

Another factor that the justice system cannot ignore is the varying motives between those who left before and those who left after 2014. A significant proportion of jihadi apprentices had already returned in 2013-2014.

Here, the profiles vary greatly. On the one hand, there are those for whom the experience as a jihadi apprentice was unconvincing. This was at a time when IS was not yet officially formed, and it is almost impossible to know exactly which group the returning ex-jihadist had belonged to or fought for. The Tunisian justice system takes a rather lenient position towards these returnees

Those who did not have Tunisian blood on their hands and who returned and surrendered voluntarily were quickly released after a few days of interrogation. This policy was in line with the statements of the then president, Moncef Marzouki.* Others had slipped through the cracks, but had already stopped their violent activities by the time they had returned. It should also be noted that a significant proportion of those who benefited from the 2014 amnesty subsequently resurfaced, both dead and alive, in conflict zones, most notably in Syria.

"If a person wants to return, they have every right to do so. No police, judicial or security authority can deny them this right."

Imen Triki is one of the leading lawyers in Tunisia for jihadists and their families. A human rights activist, she was also president of the association of Liberty and Equity between 2011 and 2014.

In contrast to the aforementioned difficulties facing the Tunisian justice system, there are others who call for the repatriation of jihadists whose conflict zone crimes have been clearly identified, and who may prove to be important sources of information in the Tunisian fight against terrorism. This is the view of Béchir Akremi, who notably interrogated the four jihadists brought back in mid-2019. For the most notorious and dangerous returnees, an in-depth interrogation by the prosecutor is necessary.

"Any Tunisian who is due to be extradited from another country will be accepted, as they definitely pose a threat."

Béchir Akremi, Investigating Judge in charge of antiterrorism, appointed General Prosecutor of Tunis in 2016.

In addition to the question of fair trials, there is also the issue of detention. The judicial authorities are fearful of the threat posed by the presence of potentially proselytising ex-combatants in prisons. The Tunisian justice system recalls how the imprisonment of returnees from Afghanistan and Iraq in the 2000s led to the recruitment of jihadists: namely the Ansar Al-Sharia movement, which was formed whilst serving prison senteces. It only took a handful of figures such as Abu Yadh to radicalise Tunisian prisons in the early 2000s, managing to rally many regular prisoners.

The issues concerning judgements and trials will take a long time to resolve, and Tunisia can offer no more of a miraculous solution than anywhere else. As the French prosecutor François Molins told me during an interview, " we don't need emirs in French prisons". The same certainly goes for Tunisian prisons. Because while the massive wave of returnees has not yet begun, it is indeed the national danger that concerns the Tunisian justice system today. The potential encounter between national actors and returnees could create an absolute nightmare of a scenario.