On this day, it was not only a man or a war commander who died, but rather an icon of the Afghan resistance. In the fight against the Taliban, the assassination of this frontline figure kindled a wildfire that would herald a previously unimaginable event that rocked the entire world. Two days later, two planes crashed into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York, and the world was forever changed. Meanwhile, the identities of commander Massoud's killers were discovered. Their nationality? Tunisian.

Massoud’s assassination had been a year in the making, orchestrated by a small group of jihadists led by a Tunisian man named Seifallah Ben Hassine, better known as Abu Yadh. He was one of Bin Laden's closest lieutenants and was said to be close to Abu Moussab Al Zarkaoui. Ben Hassine had gained his first militant experiences in the 1980s as part of The Movement of Islamic Tendency (MTI), a predecessor of the Ennahdha party. This was before getting involved in what would later become the Al Qaeda movement.

However, after the assassination of Commander Massoud, Abu Yadh's career came to an abrupt end as he was arrested by American forces and handed over to Tunisia, where he was subsequently sentenced to 43 years in prison. At the time, few people would have bet money on his forthcoming release. Not even he himself.

Ghriba and Soliman, The turning point

In the early 2000s, the phenonemon of violent extremism by so-called jihadist groups seemed foreign to Tunisia, a phenomenon that was reinvigorated in the 1990s in Algeria, Bosnia and with the U.S. invasion of Iraq. The Ennahdha movement (formerly known as MTI), did not succumb to violence, and its exiled or imprisoned leaders no longer have any political platform.

Yet, all this was surface level, for if nature rejects a vacuum, the political ecosystem will not be able to tolerate it either. As Ali Seriati* (a key figure in Ben Ali's security apparatus) confided in me: in the early 2000s, Ennahdha was no longer the main source of worry for Tunisian authorities. " W e weren’t paying attention to this phenomenon that had been brewing throughout Tunisia since 1998. We had authorised the use of satellite channels which were starting to yield results, and only became aware of this matter at a later stage..."

In the absence of a space for political contestation and free media within the country, a large portion of the population began tuning into the multiple channels that were broadcasting from the Arabian Peninsula, so much so that it started to cause concern among authorities. However, it was difficult to turn back time. According to Ali Seriati, with the rise of satellite channels, Wahhabism began to corrupt Tunisian Islam. " We only really understood this in 2002 through the Ghriba attack", he adds.

Tunisia was severely shaken by the 2002 attack, as it was the most violent event to take place on Tunisian soil thus far. However, the Ghriba attack was not immediately followed by an increase of violent events. It was not until 2007 (with the emergence of the so-called Soliman* group), that the security forces were once more confronted with the orchestration of a large-scale attack.

Five years apart, these two attacks were only the tip of the iceberg. As the diplomatic cables made public by WikiLeaks unveiled, the rampant radicalisation of a fraction of Tunisian youth had been a cause of concern for American authorities since 2005-2006. At the time, there was one lawyer who made discreet visits to the American Embassy in Tunis: Samir Ben Amor.

Ben Amor, a lawyer and political opponent, explains the motives of the emerging jihadist movement which he concludes to be a result of Ben Ali's regime. The American diplomatic cable states: " Ben Amor states that he has noticed a change in both attitude and motivation of clients in recent years. In 2002-2003, he says, there was a lot more talk of voluntarily enlisting to fight in Iraq, Palestine or Afghanistan. In the last couple of years however, there has been a stronger tendency to practice jihad in Tunisia. Ben Amor explains this development with several different factors. The youth feel marginalised in Tunisia, and there is nowhere to turn to with their grievances. They also deplore the injustice; the harassment of security forces against practicing Muslims which, according to him, has been a major motivating factor for several of his clients. In particular, he said that they were opposed to the Tunisian government's campaign against women wearing the Islamic veil." This account from 2006 reveals a radicalising atmosphere through heightened security pressure.

"The travel networks were more active before the revolution than after. Thousands of young people left for Iraq in the 2000s."

Samir Ben Amor, a lawyer and former opponent of Ben Ali, was elected to be a member of the Constituent Assembly on the CPR party list after the revolution in 2011.

the original sin

Five years later, the fall of Ben Ali and the onset of Tunisia's democratic transition reshuffled the deck and imposed what remains today one of the best gains of the revolution: pluralism and freedom of expression. However, it would be unfair to blame the violence that followed on the Tunisian revolutionary phenomenon and the wave of political freedom alone.

Without a doubt, we can date the beginning of the disaster to February 19, 2011. On this day, the decree-law 2011-1 suddenly appeared in the official gazette of Tunisia. Signed by the President of the Republic (Fouad Mbazaa), and proposed by the Minister of Justice (Lazhar Karoui Chebbi), it announced the release of all political prisoners, merely a month after the fall of Ben Ali.

1200 Salafists, including 300 ex-combatants, were released. This included members of the Soliman group… among them: Abu Yadh.

The then head of Government, Mohamed Ghannouchi, later justified this decision by referring to political pressure from “ the streets”. Yet, neither “ the streets" nor the oppositional parties had officially requested the release of violent individuals involved in blood crimes or terrorism. Was it simply a blunder? A lapse of judgment during a tumultuous time?

Is it plausible that a claim by Ennahdha alone attracted the sympathy of its most radical supporters? Possibly. A recently leaked video, most probably from 2011, shows Rached Ghannouchi of Ennahdha in conversation, stating that the Ennahdha movement had insisted on the release of the so-called Soliman group and all other prisoners, even those convicted of terrorism.

It is surprising that Rached Ghannouchi made these statements so quickly, when his movement was in the midst of restructuring and already struggling to negotiate their position in a post revolutionary context. Without potential pressure from the Ennahdha party, some of the lawyers of the Tunis bar continued to question the decree and its application. Could it also be the consequence of an inadmissible state level security manoeuvre, at a time when the Ministry of the Interior (a pillar of the dictatorship) was being seemingly decapitated by a newly appointed minister, determined to take on the security apparatus*? At least it could be according to Samir Ben Amor.

"Releasing all those accused of terrorism, including dangerous persons (...), was not an act of innocence."

Samir Ben Amor, a lawyer and former opponent of Ben Ali, was elected to be a member of the Constituent Assembly on the CPR party list after the revolution in 2011.

This is difficult to prove; yet, it is a process that is far from unheard of. As former Algerian Prime Minister Sid Ahmed Ghozali (who signed the ban on the Islamic Salvation Front [FIS] in 1991), told me at the time: the Tunisian security matters of 2011-2012 reminded him of the way the Algerian army allowed Islamist demonstrations to spill over into the streets during the late 1980s, instead of containing the movement to the political sphere. This move allowed the army to reposition itself at the political center of gravity, as a bulwark against violence, as well as maintain control of the Algerian economy in crisis.

Therefore, we are faced with two scenarios: either Ennahdha's willingness to reassure its radical supporters, or intentional neglect of security. These are not mutually exclusive. In fact, both of them continued to be credibly hypothesised throughout the corridors of the Tunis courthouse, which had to deal with the brunt of the problem a few years later.

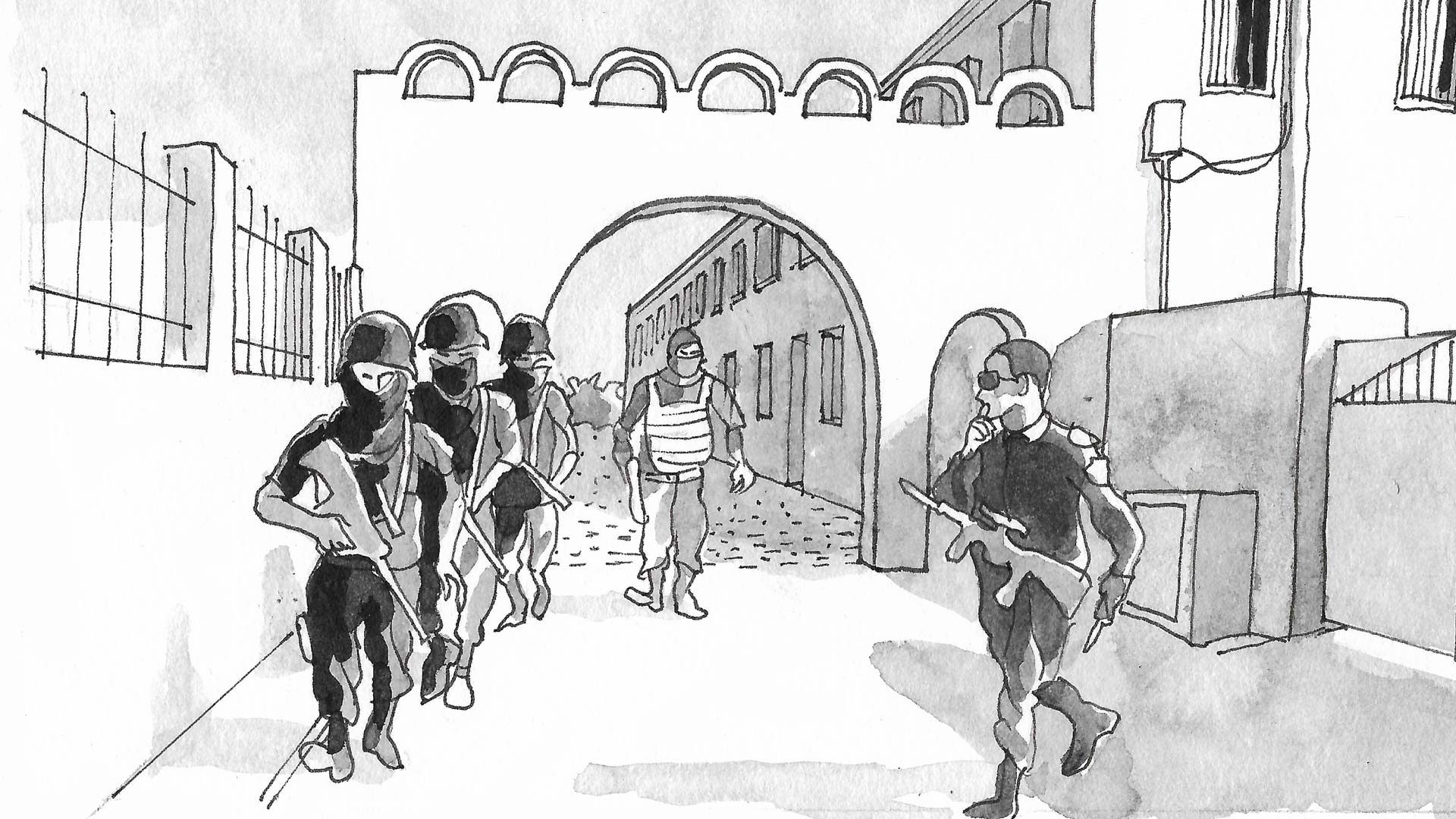

ANSAR AL-SHARIA’S RISE TO POWER

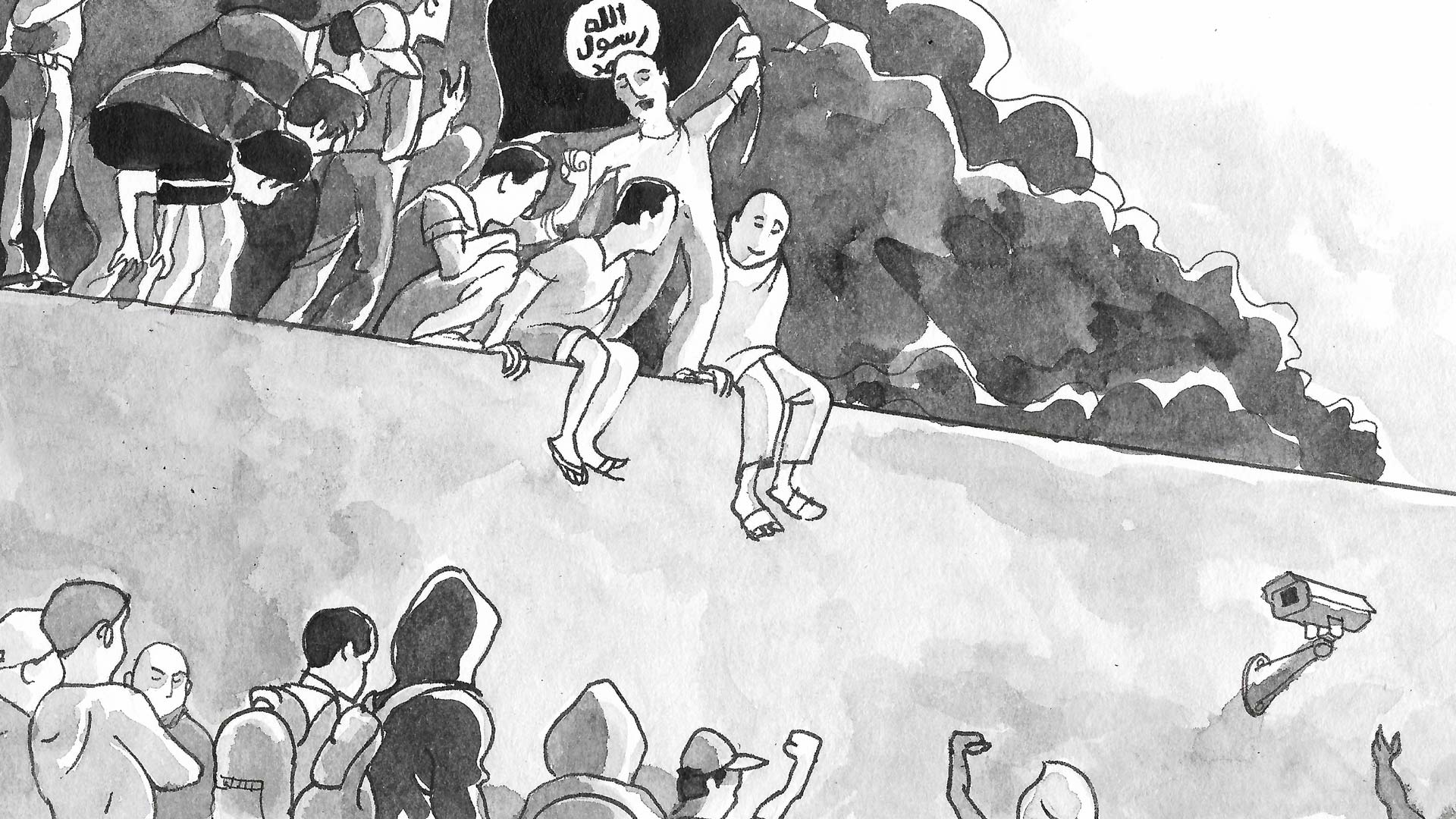

Whatever the motivations and errors behind this original sin, what follows is a notable worsening of security conditions. Combined with a conducive regional context, the ingredients of this explosive cocktail were in place by March 2011. This explains the surprising speed at which Tunisian " takfirist" movements exponentially spread in less than a year. Abu Yadh is quick to establish a movement that was previously unheard of in Tunisian politics: Ansar Al-Sharia; a movement that rapidly attracted a large number of young Tunisians.

From the onset, there were lively debates within the movement about which strategy should be adopted. At a meeting in La Soukra in 2011, Abou Yadh initially pleaded for the gradual establishment of his movement, and expressed his wish for a peaceful approach. He then entered into negotiations with Ennahdha, who thought that they would be able to control him at the time. At first, Ansar Al-Sharia were satisfied with preaching, sometimes accompanied by helping people in need throughout the most impoverished regions. Tunisia was not yet considered a land of jihad.

However, the movement quickly and secretly began to prepare for other, illegal, phases of action, with the aim to possibly move from the dawa* phase to the jihad phase on Tunisian soil. This was carried out freely and with relative impunity. By 2013, the Ansar Al-Sharia movement had become the main promoter, trainer and organiser of apprentice networks for young Tunisian jihadists being sent to conflict zones, mainly Libya but also the Syria-Iraq region.

In 2012 and 2013, the Troika alliance (the Ennahdha movement in particular), were accused of, at best: turning a blind eye, and at worst: encouraging the departure of young jihadist sympathisers to conflict zones. While it is not proven that Ennahdha was fully involved as a political entity, statements by some of its members and evidence of collaboration at a local level between Nahdhawi activists and travel networks, all suggest that the movement was accepting of Ansar Al-Sharia’s activities.

There are additional and concurrent circumstances that could further explain things. For example, Daesh (ISIS) did not exist yet, and the networks of fighters with takfirist tendencies in Syria were still small - with the exception of Jabhat Al-Nosra, whose influence was getting noticeable throughout pockets of insurgency. So why would anyone want to arrest radicalised young people, who are not desirable in their country of origin, and who want to fight Bashar Al Assad? Because the latter is a strategic adversary whose downfall was considered to be just within reach.

Formulated in this way, the question might seem cynical. But in 2011 and 2012, this reasoning seemed to be present in policy-making in the countries from which the jihadists originated: Tunisia, Saudi Arabia and Europe. In Belgium, for example, the debate among certain political leaders even went so far as to consider the character of the fighters, considered first and foremost as simple international brigades.

Therefore, there was nothing unusual about the lax and rather tolerant position displayed by Tunisia in this context; a position, which, like other countries of origin, shifted between mid-2013 and early 2014. This was at a time when Tunisian political authorities had become fully aware of the danger that these foreign fighters posed to the country.

"After 2014, certain measures were taken to be able to stop the phenomenon."

Judge X is one of the judges appointed to the Antiterrorist Pole of Tunis. For security reasons he requires to remain anonymous.

Several factors that were specific to Tunisia explain the disproportionate extent to which Ansar Al-Sharia grew and consolidated within the country. Prosecutor Béchir Akremi (in charge of cases related to terrorism at the time), points to three main contributing factors: the destabilisation of the domestic intelligence sector leaving an operable vacuum; the reconfiguration of border control as a result of the revolution; and lastly, the breakdown of central power in neighboring Libya which paved the way for the complete destabilisation of Africa's "ar ms depot ", thus facilitating the importation of arms into Tunisia.

"Additionally, several terrorist fighters return from abroad, especially from Europe, including terrorist leader Boubaker El Hakim."

Béchir Akremi, Investigating Judge in charge of antiterrorism, appointed General Prosecutor of Tunis in 2016.

There is one last factor that could be added: in 2012, Tunisian judges still did not have the necessary antiterrorism skills. There are few resources to identify the masterminds behind the attacks, or to conduct in-depth investigations into the channels through which the attacks were carried out.

"The new security apparatuses weren't prepared for this, and neither was the judicial system. Meanwhile, terrorism was spreading."

Béchir Akremi, Investigating Judge in charge of antiterrorism, appointed General Prosecutor of Tunis in 2016.

In mid-2011, several groups, particularly the two main branches of Tunisian jihadism, were competing for space in the world of takfirist extremism. On one side there was Ansar Al-Sharia, who united former members of the Soliman group with former prisoners, all committed to their leader Abu Yadh. The movement was supported by a discreet but effective armed branch that was being gradually established in the shadows, under the initiative of two former prisoners with troubled pasts: Ahmed Rouissi and Boubaker El Hakim. The latter would be responsible for remotely organising the attacks in Paris and Brussels from Raqqa a few years later.

On the other side, there was a circle being formed in central Tunisia, 30 km west of Sidi Bouzid, headed by El Khatib Al-Idrissi (the blind sheikh), who did not see the need for an organisation. While he refused Abu Yadh's alliance proposal, he did not deny his support. Even though Al-Idrissi's followers were among the first to import weapons into Tunisia, there was no evidence proving that Al-Idrissi personally ordered these initiatives.

Let us take a few moments to examine the background and personality of the two emblematic figures of Ansar Al-Sharia's armed wing: Boubaker El Hakim and Ahmed Rouissi.

The Franco-Tunisian El Hakim, was released from prison in France on January 5, 2011. This seasoned jihadist was immersed in a radical family environment from an early age, before making a name for himself in 2003 as the founder of the so-called Buttes-Chaumont* network, working mainly on behalf of Abu Moussab Al-Zarkaoui. This network would prove to be very effective in sending French jihadists to fight the American army in Iraq. El Hakim became further radicalised, left for Iraq, acquired his jihadi credentials, but was ultimately caught upon his return to France and sent to prison. After serving his sentence, he decided to return to Tunisia, and offered his services to Abou Yadh as soon as he arrived in the country.

Ahmed Rouissi’s character is much more troublesome. Close to the networks of Ben Ali supporters who were disgraced and imprisoned after the revolution, he put his skills and networks to use for Ansar Al-Sharia from 2011, without anyone knowing exactly who he worked for. This was the typical profile of an intermediary with multiple allies. Was he indoctrinated by Abu Yadh or his followers during his time in prison? Did he place potentially lucrative networks at their service? Did he act out of conviction? Or was his motive financial gain from multiple employers? Whatever the motive, he became the main organiser of the channels sending Tunisian jihadi apprentices into Libya, and managed the local training, particularly in the Sabratha camp.

In 2012, these two branches, (on the one hand the El Khatib Al-Idrissi entourage, and on the other El Hakim/Rouissi), reach an agreement during a meeting in a small house just outside Ben Guerdane, close to the Libyan border, which would also serve as a weapons depot until 2016.

At this meeting, they declared that, for them, Tunisia would henceforth become a land of jihad. It was there that the collaborators set the basis for the actions that would violently destabilise the already fragile democracy between 2013 and 2016.

Located only a few kilometers from the Libyan border, Ben Guerdane was not a random choice for a meeting spot. Away from the main road, all traffic has to pass through narrow sand and pebble roads. In March 2016, the town was attacked by more than 150 jihadist fighters from Libya, and its inhabitants, to the great surprise of the jihadists, collectively united against the attackers, reinforcing the Tunisian security forces.

" If Ben Ali was still around, the citizens would have sided with the jihadists", jokes Mustafa Abdelkebir, a local resident who runs the Tunisian Observatory for Human Rights (OTDH) between his border town home and Medenine (where his offices are located). He had been witnessing these activities since the shift in 2011-2012.

"There was an isolated house a few kilometers from the city. They met there to decide whether Tunisia would be a land for jihad or dawa. That's where their operation started."

Mustafa Abdelkebir, activist from Ben Guerdane, and president of the Tunisian Observatory for Human Rights (OTDH), based in Médenine.

FROM NEGLECT TO REPRESSION

However, following the meeting in 2012, it took the political authorities a few (long) months and additional prominent developments before they reacted and decided to put an end to these underground activities. The attack on the American embassy* on September 12, 2012, marked a turning point in relations between the executive and the radical fractions of Tunisian Islamism.

Accused of sympathising with the events, notably implicating the then Minister of Religious Affairs (Nourredine El Khadmi of Ennahdha), Rached Ghannouchi was pressured by the American administration to start offering guarantees.

Tolerance was replaced with repression. Six months later, Chokri Belaïd was assasinated and Boubaker El Hakim claimed responsibility for the assassination with a video and in Dabiq, the propaganda media outlet of the Islamic State. Additionally, this was carried out with the complicity of Ahmed Rouissi. While the true instigators behind the assasination remain unknown to this day, the event marks the climax of the tension between the Troika allicance and Ansar Al-Sharia, that would continue until the assassination of Mohamed Brahmi.

Ali Larayedh, the then Minister of the Interior and Head of Government, ordered the movement to be banned and its members arrested at the end of August 2013. This belated political decision led many members of Ansar Al Sharia to engage in clandestine violence in Tunisia, and/or to flee via Algeria and Turkey to Syrian or Libyan conflict zones (particularly in the Sabratha camp). It was at this time that the Tunisian justice system began to set up a system of border screening, through which nearly 12,000 people were prevented from leaving the country*. The departure phenomenon started to be contained, much much too late.

The remaining members of Abu Yadh's movement, who had gone underground or returned from abroad, subsequently subject Tunisia to an unprecedented string of violent attacks. Most of these are remotely organised from the Sabratha camp in Libya, under the command of Ahmed Rouissi, among others. The camp would later be bombed by the U.S. in early 2016, and the jihadists attack on Ben Guerdane in March 2016 could be seen as retaliation for this bombing of Sabratha.

"Since 2016, terrorist attacks have been on the decline, and several operations have been aborted."

Béchir Akremi, Investigating Judge in charge of antiterrorism, appointed General Prosecutor of Tunis in 2016.

Towards the end of 2016, jihadist violence was still present, albeit sporadic and with a largely diminished magnitude. The year also marked a turning point in the fight to control arms supply to terrorist groups: arms trafficking started to be more or less contained, making it possible to decrease the level of violence. Additionally, the groups could no longer restock materials such as telephone chips, etc., and benefit from their mountain logistics. This official regain of control through direct negotiation with border traffickers continues to bear fruit to date. There are currently only 40 to 50 active jihadists on Tunisian soil; living in refuge in the mountains, largely depleted and without the option of large-scale operations.

While on the run, Abu Yadh would be declared dead several times, first in Libya in June 2015, then again in February 2019. More credible was the AQIM’s official death announcement in Mali, March 2020. As for Ahmed Rouissi, he was killed during a battle in Sirte, March 2015. Boubaker El Hakim was in turn targeted and killed by an American bomb in November 2016, with the approval of French authorities. El Khatib Al-Idrissi continues his preaching not far from Sidi Bouzid, without any established or illegal personal links to armed groups.

However, there is a good chance that the renewed tension in the Libyan conflict may again destabilise Tunisian territory in the near future, albeit with one notable difference: the experiences of the past ten years have considerably strengthened the institutions working with antiterrorism, both at a security level and the justice system itself.