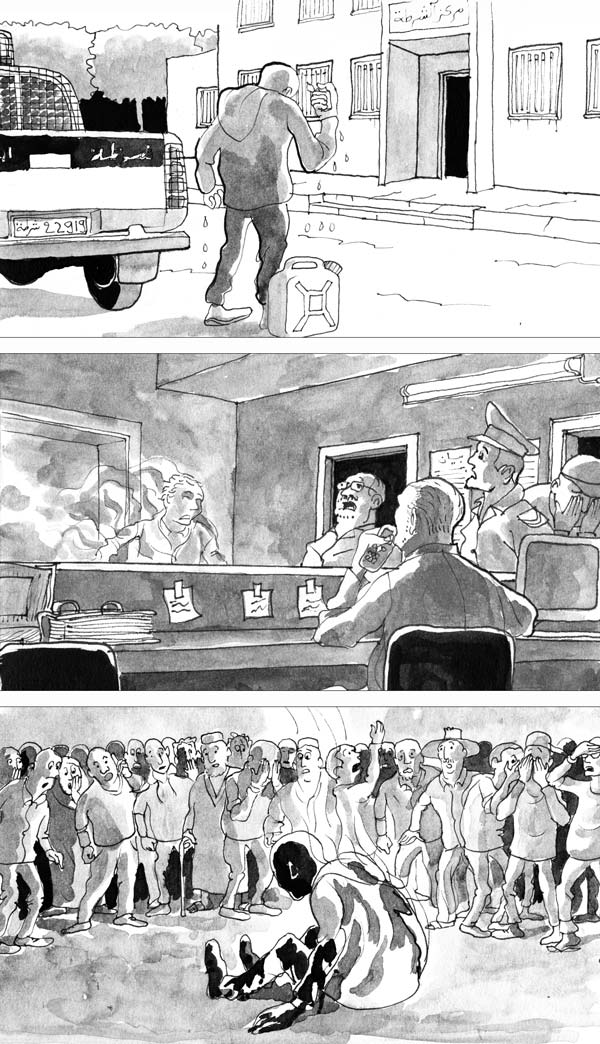

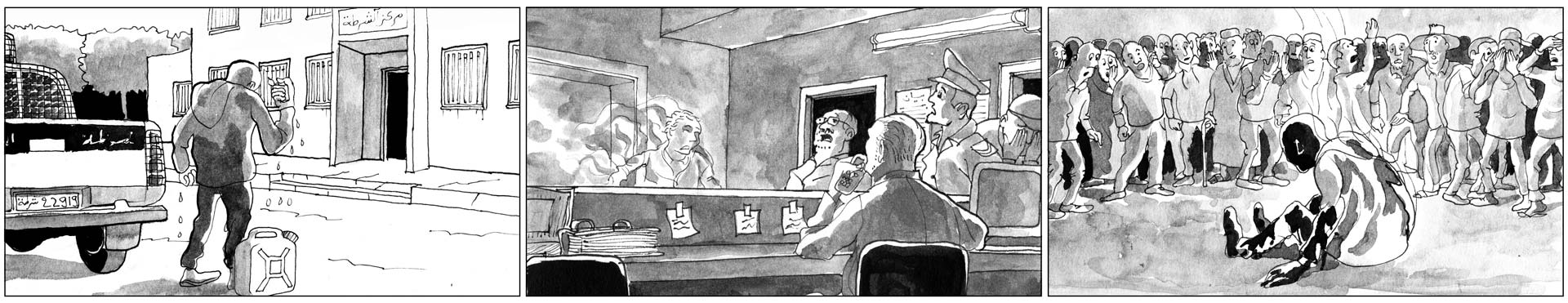

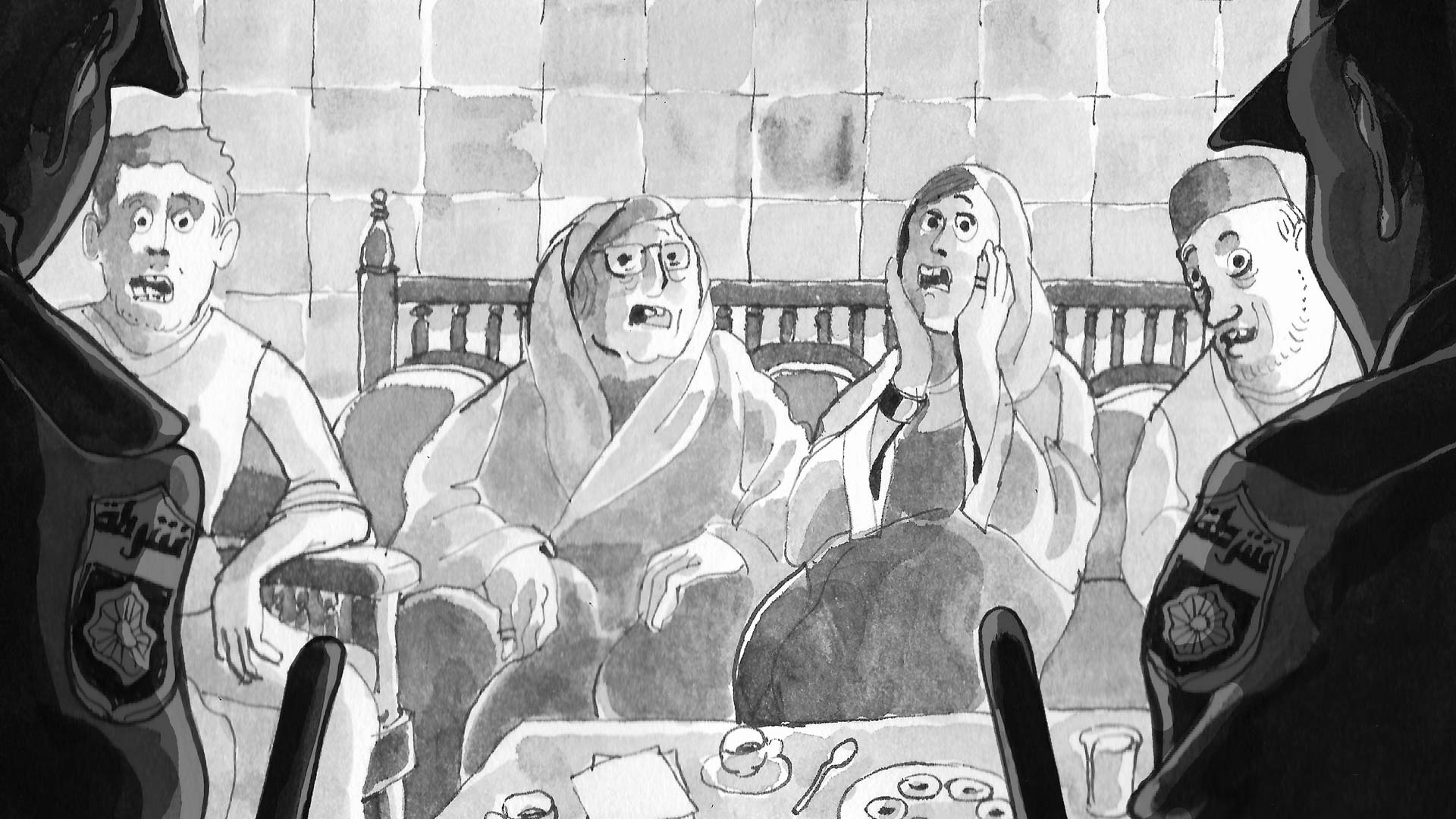

On September 5, 2018, the 30-year-old Mohamed Dhia Arab left his family home, a small modest house tucked away at the end of a narrow street, he walked about a kilometre and stopped in front of the police station at the city entrance. Nobody paid him any attention. He unscrewed the cap of a petrol can, slowly doused himself, took out his lighter, and set himself on fire. Stunned, the customers at the café across the street watched as he calmly walked on, without a trace of anguish. The young policemen who were on duty in front of the station were terrified, and hurried to return to the police station.

Mohamed Dhia Arab followed suit, and entered the police station calmly. The policemen panicked and left in a hurry. He kept following them, walking, just like in a horror film. But this was real life. He exited, sat down, and waited to be consumed by the fire. Completely frozen and shocked, neither the witnesses nor the police intervened. No one thought of trying to save him, using the fire extinguisher at the police station or at the café.

The ambulance arrived two hours later; two long hours of agony. Mohamed Dhia Arab died the next day in the Rabta hospital as a result of his injuries. The event was shrouded in silence; surely not a case of censorship, but an oversight. Seven years after the Revolution, no one was interested in self-immolation anymore, and even less so when it concerned a young man who has been marked with the infamous and invisible "S17" stamp.

Only a few years earlier, such descent into despair or thiis type of tragic suicide would have been unimaginable. How did the fate of Mohamed Dhia Arab come to this? Let's delve into the origins of this story. When you first visit his Facebook page, he appears to be an ordinary boy, taking pictures of himself in front of his favourite sports cars, particularly in Italy, where one of his uncles had found him a job in 2011.

"Not being able to see his father before his death, nor being able to bury him, suffocated him."

Samia Lawsen, mother of Mohamed Dhia Arab.

In February 2014, Mohamed Dhia's life was transformed with the death of his father who he was very close to, and whose funeral he could not attend due to visa issues. For the following year, the family lost all contact with him and received no news of his whereabouts. When the telephone rang a year later at the family home, it was not the voice of Mohamed Dhia on the other end, but that of a policeman from the antiterrorist brigade of Gorjani.

"They confiscated his papers and money, and brought him straight from the plane to Gorjani."

Samia Lawsen, mother of Mohamed Dhia Arab.

Expelled from Europe for having attended a questionable mosque in the middle of his depression, Mohamed Dhia was immediately and forcefully interrogated during the initial round of questioning conducted by the antiterrorist authorities. Not much came of it, except the fact whilst in exile the young man seemed to have seeked answers during his psychological crisis in dogmatic faith; nothing that could link him to any sort of terrorist network. Several days later he was released from police custody, but with an S17 record.

Mohamed Dhia Arab had a difficult time when returning to Menzel Bouzelfa: professional failure, lack of prospects, and the painful absence of his father. He nevertheless tried to reintegrate into local social life by looking for work, but incessant police intervention was never far away.

"He asked us not to say a word about it."

Samia Lawsen, mother of Mohamed Dhia Arab.

A BODY SURVEILLED: A BODY HARASSED

This situation is experienced by thousands of young Tunisians, the mother of all indignations, of all revolts, and at times even, of all resignations. Mohamed Dhia's situation may just as well never have degenerated in this; his daily life simply but tirelessly repeating itself until he catches a lucky break. But then there was his S17 file, constantly reminding him that he was not a regular civilian like the others. To the police and his neighbours, he was a condemned soul and another body to keep a watchful eye on.

The police officers at the local police station made weekly raids on their house, ransacking their worn-out furniture and threatening the family; brutally reminding Mohamed Dhia that they had him under surveillance. Several months went by as the police intrusions became more frequent than job offers. It was an infernal circle.

"He didn't know what he had done wrong or why they were doing this to him."

Skander, brother of Mohamed Dhia Arab.

In the end, Mohamed Dhia Arab ‘decided’ to self-immolate. Some would have preferred to blow themselves up in front of a policeman with a home-made explosive device, others would have suffered in silence until quietly committing suicide. As psychologist Rim Ben Ismail explains, the experience of state inflicted violence can often be redirected against oneself, or against the armed wing of the state; the police.

"It’s really counterproductive, because with this filing system, we are producing violence."

Rim Ben Ismail is one of the few psychologists working in prison with detainees involved in cases related to terrorism.

In the case of Mohamed Dhia Arab, the accumulated violence ended up being directed against himself and whatever was symbolic for state authority.

"Are you going to report police officers to the police? No one would be on your side."

Skander, brother of Mohamed Dhia Arab.

In an unusual move, Mohamed Dhia's family decided to file a complaint with the help of a young lawyer, Wissem Othmani.

"Law enforcement agents use harassment to extort people."

Wissem Othmani. A former Salafist activist who became a lawyer at the Tunis bar in 2011, Othman remains close to radical Islamist circles. He is the lawyer of Mohamed Dhia Arab's family.

At first, the lawyer filed a complaint against the police station that was indicted by the family. After several refusals and appeals, the complaint was deemed admissible by the Grombalia prosecutor, before ultimately being dismissed. For the public prosecutor, Mohamed Dhia Arab committed suicide. Full stop.

One could feel reassured in thinking that Mohamed Dhia Arab's case as anecdotal, to classify it as a random incident, some kind of collateral damage of a rarely challenged fight against terrorism. Why would you then evoke the memory of a young man suspected of being radicalised? Because his case and the brutality of its rare culmination conceals thousands of similar and equally invisible judicial fates; uncovering a part of reality that is difficult to fully fathom.

As an administrative decision, the Ministry of the Interior maintains the obscurity of these files, thus escaping any juducial scrutiny. The exact number of files is unknown, and the nature of the files is unclear. How many people are on the S17 list? Officially, 30,000 people* were prevented from travelling between 2013 and 2018, although it is not known whether they were all on the S17 list.

In addition to this, there is a large number of people who will never find out that they are on the list unless they intend to travel. If you then add the people under different forms of “house arrest”, the figure could quickly exceed 100,000 individuals, out of a population of 12 million.*

The S17, but also S1-S18 and S19* databases were initially set up to conduct border controls on suspicious persons or individuals presenting a threat due to their proven proximity to radical groups. Up to this point, there was nothing unusual about justifying the existence of intelligence files, if they allow for better monitoring of individuals presenting a potential danger to the nation.

"These people are also controlled when they move internally. If a person travels from one city to another, he or she will be stopped by the police and questioned. "

Judge X is one of the judges appointed to the Antiterrorist Pole of Tunis. For security reasons he requires to remain anonymous.

S17: A SENTENCE WITHOUT A CHARGE

Such justifications for security databases began to crumble as the list gradually expanded to include all those considered likely to be dangerous, and those thought (as opposed to proven) to have links with radical groups or terrorist enterprises. For some, merely attending a particular mosque or having a family member who went to Libya may be considered valid grounds for being on the list. Wearing a niqab or a beard may also be sufficient. It may even be enough to denounce a neighbour with malicious intent.

Judges, lawyers and families are not aware of the classification criteria which remain a complete mystery as they are not subject to any court decision. The fact that tens of thousands of individuals can be convicted administratively, without any evidence or court decision, poses a serious problem. The arbitrariness of such decisions is denounced by lawyers and occasionally, though more discreetly, by judges. It should also be noted that this file system contradicts Article 24 of the Constitution.* But in the absence of a Constitutional Court, how can this be challenged?

"Even on my way to the café I'm afraid. I have been arrested several times at the café and brought in for questioning."

'Y.' - a S17 listed person who requested anonymity.

As in the case of Mohamed Dhia Arab, or according to the testimony of 'Y.', psychologists denounce the serious impact that these measures have on the mental health of those concerned. Therefore, when harassed, some of the victims also choose to return to a conflict zone. This was the case for the brother of the famous rapper DJ Costa, who, after fleeing from the Syrian front and openly returning to Tunisia where he was subsequently amnestied, was constantly harassed by judicial controls. These security pressures ultimately pushed him to rejoin the Syrian front.

"These people are the living dead; their lives are taken away when they are supposed to be free."

Rim Ben Ismail is one of the few psychologists working in prison with detainees involved in cases related to terrorism.

Another consequence is that these measures legitimise police misconduct, meaning the police are no longer held accountable by any institution. In practice, they provide a legal framework for police harassment. At the Menzel Bouzelfa police station, the police officers defend themselves from harassment accusations, claiming that they were only doing their job. Deep down, they too feel a sense of unease.

The front that the police officers' put up poorly conceals another reality that needs to be taken into account: in Menzel Bouzelfa, where around twenty young people are listed under S17, the files are incomplete, and the police officers themselves are often unaware of the content of the charges or the origin of the files. It is therefore impossible for them to know whether the person on file has been directly involved in a terrorism case, or whether he or she is, for example, simply the second cousin of someone and not proven to be involved.

Thus, police officers often find themselves overwhelmed by files full of details that remain unknown, with time-consuming consequences and daily fears: what if a person listed under S17 were to carry out an attack? This is a situation experienced by every police station in the country. Initially confidential, the subject eventually became public, and its purpose was questioned.

“This debate hides yet another one: are these measures really effective in the fight against terrorism? The security forces and the Ministry of the Interior say 'yes' without hesitation. Yet, one may very well challenge this, as among all of the terrorists involved in attacks on law enforcement agencies since 2017, none were subject to surveillance.”

Minister of the Interior Hichem Fourati, during his hearing before the ARP in June 2019.

The Minister of Interior eventually appeared before the Assembly of People's Representatives (ARP) regarding this issue in June 2019. Reaffirming the benefits of the database, he nevertheless stated that the procedure would henceforth be limited to border control, and that 1,000 names had just been removed from the list, though once more without specifying out of how many cases.

Following the release of an uncompromising report by OMCT which generated a great deal of attention, the issue of these databases was again raised in the media in December 2019.

Béchir Akremi, Investigating Judge in charge of antiterrorism, appointed General Prosecutor of Tunis in 2016.

Would a solution involve strict judicial control over the filing of data, with the right to appeal? This solution would be more than possible and has been a long-standing proposal, but for the time being it remains merely a pipe dream.