Behind her desk, she flips through the reported cases, handwritten on loose papers. Their stories are incomplete. A brief note reads that the girls are between 9 and 17 years old. All of them come from Tunisia’s marginalized interior regions, from areas such as Fernana, in the governorate of Jendouba, and Cherarda, in Kairouan, to the rural outskirts of Bizerte, in the North, and Kasserine, in the West. The young girls are forced to leave their families and education behind to serve as domestic workers.

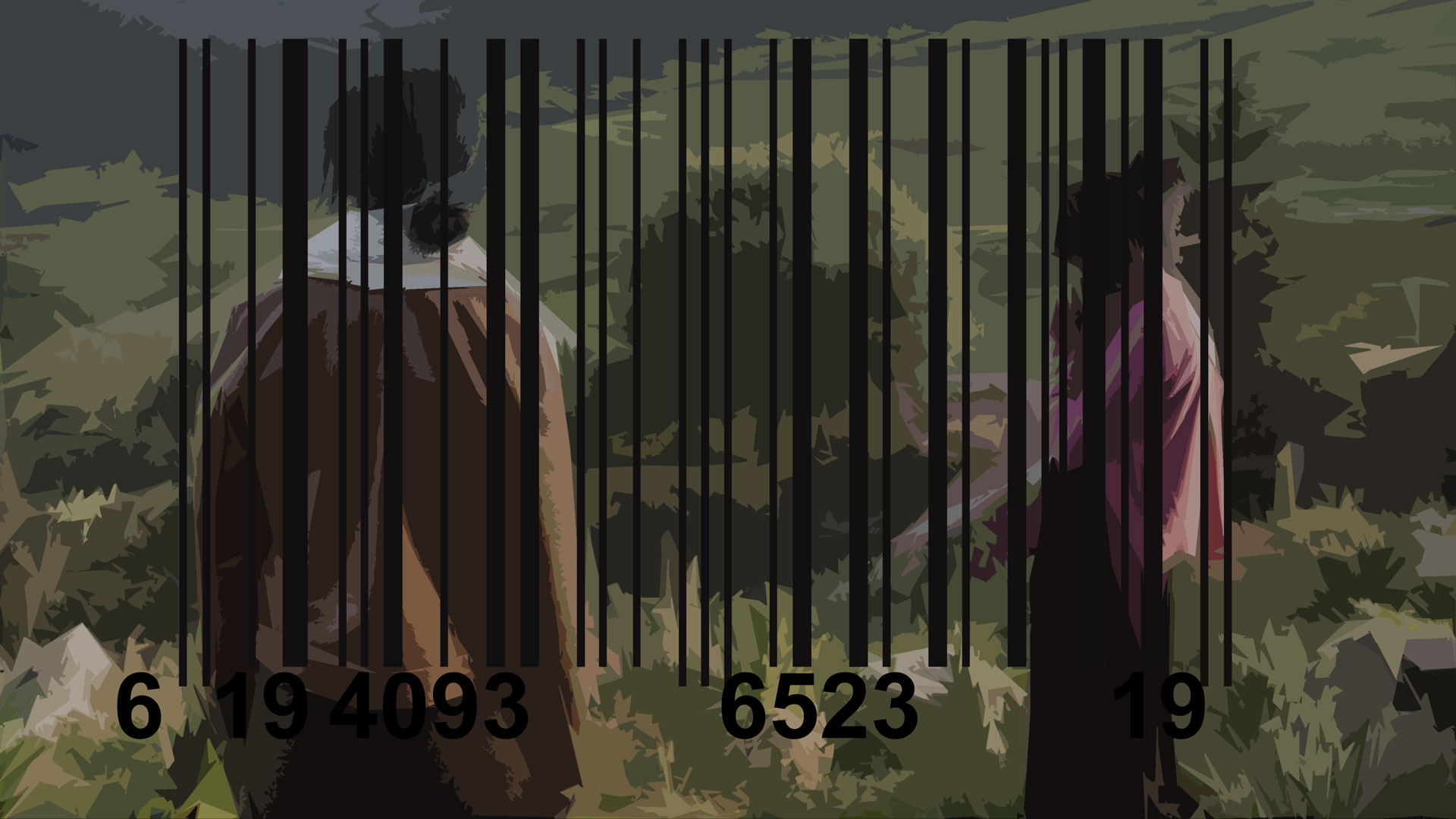

Confined inside and kept out of sight, young girls forced into domestic servitude often remain undetected. “ People need to be made aware [of this problem] so that they can report these cases,” says Raoudha Bayoudh.

Even the Ministry of the Interior has limited means of recognizing and addressing this issue; taking action is dependant on receiving alerts about suspicious activity or a related crime. These alerts typically come from child protection officers based around the country, injunctions issued by a public prosecutor, or cases reported on Facebook or other social media platforms.

But in most cases, victims of domestic servitude get noticed for reasons unrelated to their labor. “ It may be about sexual assault that occurred in the house where she works or because she was accused of theft – oftentimes wrongly– by employers who want to intimidate her,” explains Raoudha Laâbidi, president of the National Authority for the Fight Against Human Trafficking (INLCTP).

One story of domestic servitude inspired a swift community response after being publicized on social media. With just one photo featuring a young girl and her “ employer,” social media users gathered information, and as a result, “ the police found and arrested the woman in a very short amount of time, and the victim was taken care of,” recounts the INLCTP’s president.

According to Raoudha Bayoudh, this girl’s case was not entirely new. Previously, when she stopped appearing at school, child protection services were alerted and a judge intervened, ordering her back to school. Just a few months later, however, she was sent back to work, reportedly by her father.

“ It happens that a child is exploited again after their case is resolved. There is no follow-up system, and the resources are insufficient,” confesses Laâbidi. “ Unless another issue is reported.”

In 2017, child protection officers “ took on” more than 13,000 reports, nearly half of which concerned girls. In all, only a small minority of the cases directly mentioned economic exploitation and begging; there is no category for domestic servitude.

According to the National Authority for the Fight Against Human Trafficking (INLCTP), 742 Tunisians, both children and adults, fell victim to human trafficking between April 1st 2017 and January 31st 2018. More than 10% of the trafficking victims were forced into domestic servitude; how many of them were children is not specified.

“ For children, the most detectable cases involve organized crime and begging. There hasn’t yet been an adequate investigation into underage domestic workers,” says Raoudha Laâbidi.

To tackle this issue, Laâbidi is working to spread awareness through widespread educational campaigns. “ We’re living in the midst of trafficking without knowing it. Today, people are starting to hear about modern slavery and realizing that ‘employing’ a young girl is a crime.”

In 2017, the Ministry of the Interior looked into 184 cases potentially linked to human trafficking, leading to around 20 arrests. Of these cases, 11.4% were related to domestic servitude and five involved underage victims.

The individuals arrested in connection with cases of domestic servitude fall into three categories: employers, parents (or legal guardians), and intermediaries.

“ The intermediaries have three main ways of conducting business,” says Raoudha Bayoudh. Under the “ traditional” method — the most risky and now most rare — the intermediary can be found in public places, such as cafés or weekly markets.

But with the rise of media attention directed towards this issue, intermediaries have become even more discreet, working exclusively through word-of-mouth or specialty sites online.

The third method revolves around interregional connections: intermediaries living in big cities “ help” families that they know in marginalized regions to find employers for their daughters, in exchange for commission. “ Sometimes they even do it for free, just to help,” says Raoudha Bayoudh.

One of the cases taken up by the Ministry of the Interior involves this last type of intermediary. The Ministry’s representative recalls that “ her bank records revealed more than 30 small transfers,” before admitting regrettably that they were ultimately unable to prosecute. “ If the justice system doesn’t enforce the law, it’s just as if we hadn’t done anything.” But what law is there to enforce?

In August 2016, a law against human trafficking was passed. The law puts in place heavy penalties for perpetrators, especially for those convicted of trafficking children into domestic servitude: a 50,000 dinar fine and 10 years of jail-time, plus the potential for additional “ aggravating circumstances.”

Just one year later, the Assembly passed the law on the elimination of violence against women and children. Article 20 of this law refers specifically to “ domestic workers” and, remarkably, penalizes the employers and intermediaries with a sentence that is 20-times lighter than the one laid out in the 2016 law. Whether considered an offense or a crime, the same act faces two different penalties in two different laws.

“ Is this schizophrenia in our legislative system?” asks Raoudha Laâbidi. " When you treat the situation in such an ambiguous way, equality before the law is not guaranteed.”

As president of the anti-trafficking agency, Raoudha Laâbidi calls for Tunisia’s labor law, as well as other, more targeted legislation, to add language that specifically disallows child labor. Should this happen, agriculture and fishing are two other industries that would likely be impacted. “ We can easily determine who the target populations are. If we consider that they’re children until the age of 18, they shouldn’t be put to work, full stop.”

Traditionally, judges in Tunisia have been reluctant to enforce laws that punish child exploitation.“ There are no prison sentences. In general, they’re just fines,” claims Raoudha Bayoudh. Additionally, discrepancies between the laws impede their widespread application.

In 2017, only 18 cases linked to child exploitation were heard, seven of which were qualified as “ human trafficking.”

Nearly all of the victims were children, and the majority were girls. Of the 21 defendants, only one was convicted. The defendant was charged with exploiting a child for the purpose of begging and was sentenced to one month in prison. She is currently at large.

Data from the Ministry of Justice indicates that the majority of these cases were still under investigation as of January 31st, 2018. One of the cases was dismissed and the defendant was released; the other 8 remained in police custody. All of the defendants were accused of trafficking.

“ You will be surprised by the number of cases today compared to last year,” says Raoudha Laâbidi, president of the National Authority for the Fight Against Human Trafficking (INLCTP). She lists the various steps her team has implemented to combat acts of trafficking, such as trainings geared towards security officers and judges and awareness campaigns geared towards the general public.

“ I can’t say that all police officers, judges, or prosecutors have been trained, far from that, but there have been results.”

Irreparable emotional damage, stolen childhoods, poor living conditions . . . “ regardless of the financial situation, children shouldn’t have to pay the bill.”