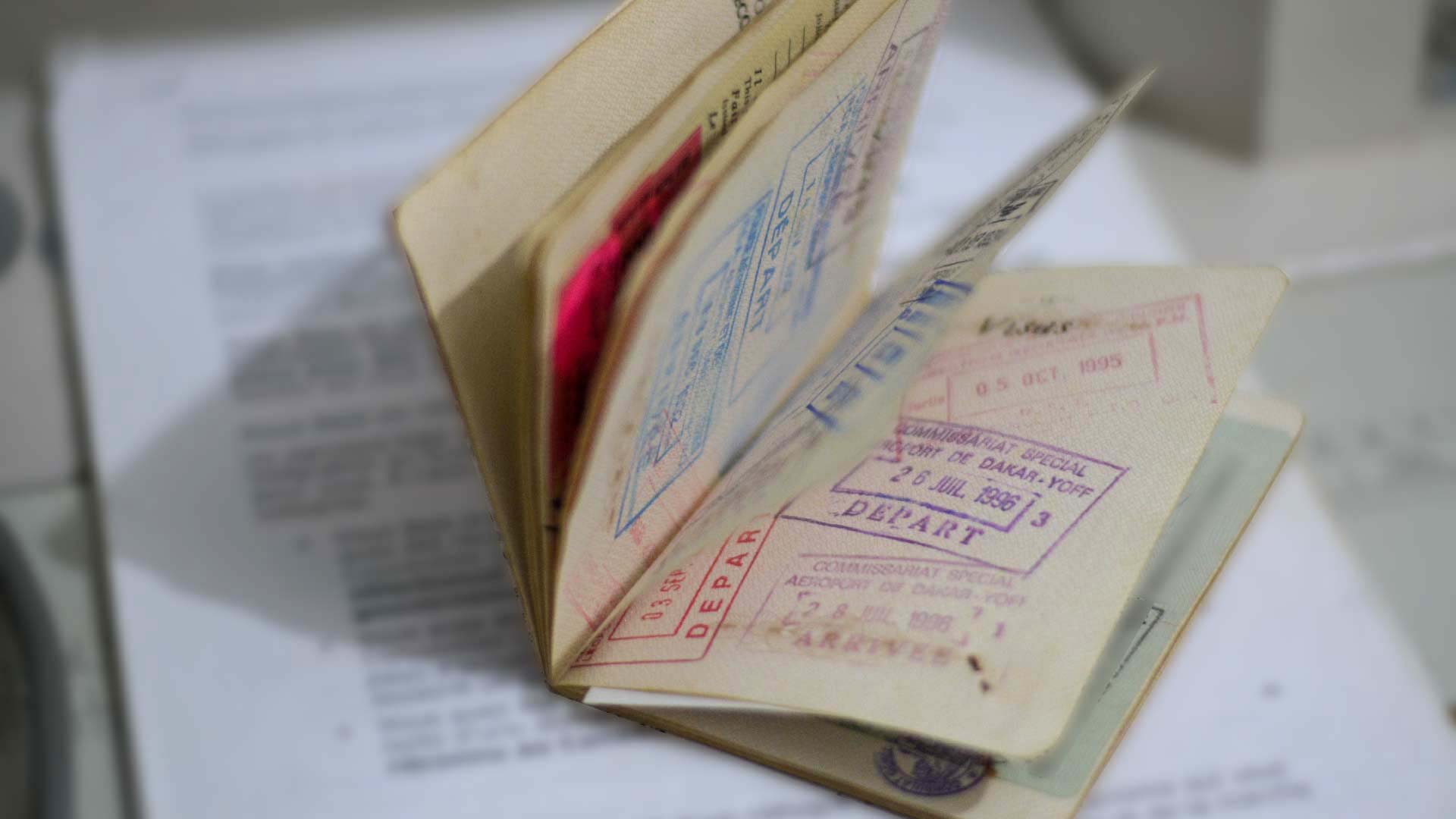

The crowded entry and exit stamps on Cléo’s passport retrace her chaotic journey.

A hasty departure from Abidjan

Cléo begins to tell her story in bits and pieces. From an early age, she doesn’t feel like she fits into the “boy” category assigned to her at birth. As a child, she refuses “ to dress like a boy.” During her teenage years, which she spends in Ivory Coast, she is considered “ too feminine for a teenager.” She lives with her father who constantly criticizes her behavior and attends an all-boys high school where the situation is equally harsh.

“ People didn’t know whether I was a girl or a boy because I looked quite androgynous,”she explains. “ I didn’t have many friends, apart from two or three gay boys, and I faced a lot of rejection.”Cléo gets harassed. One day, almost all of the school kids wait for her and a friend to enter the building. “ They welcomed us by banging on the walls and tables and shouting ‘Fags! Fags!’”

Fed up with the bullying, Cléo begins to organize meetings in which she and her classmates would discuss issues impacting the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) community. “ I revealed that I was transgender during my final year,”she says, “ and I found support. This also encouraged other students to reveal their homosexuality.” Her father finds out and kicks her out of the house. No other family members want to take her in. Eventually, “ a great friend” hosts her for the rest of the year and helps her to pass her baccalaureate exams, as best she can. “ At the end of the year, my mother decided that it would be better for me to stay with her in Benin, where she could protect me.” Cléo leaves Abidjan in 2010.

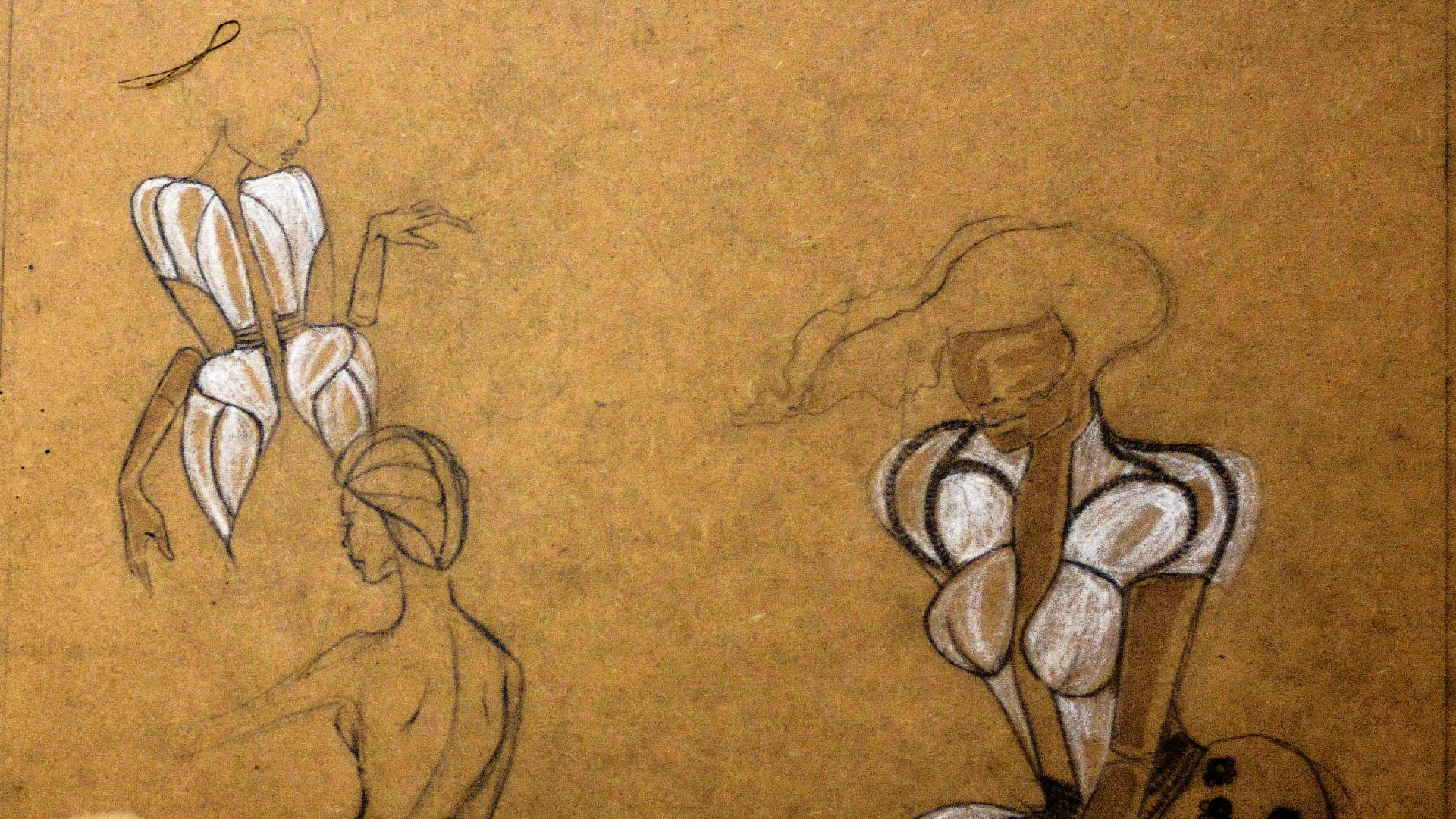

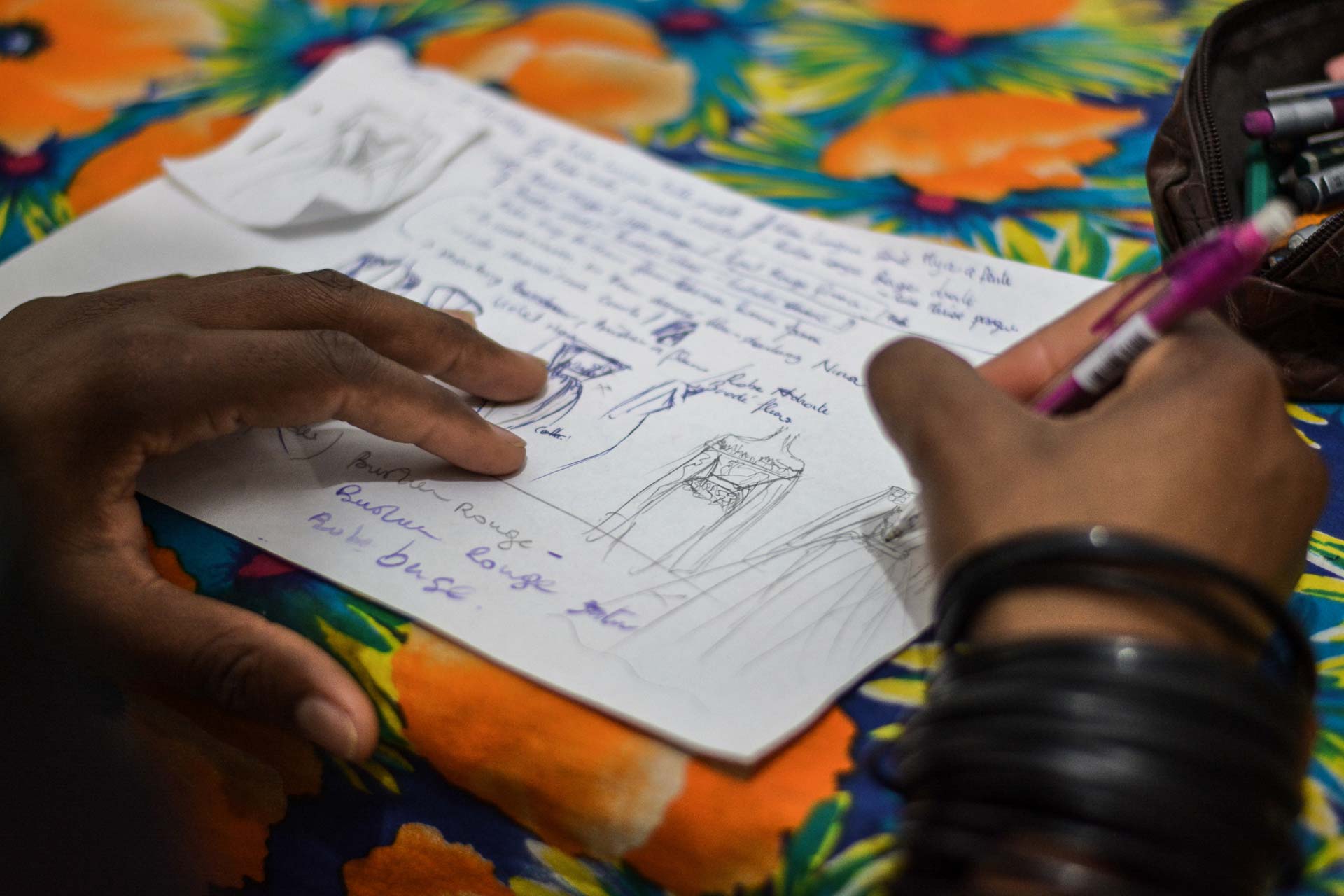

Cléo recounts her story from her studio, where drawings on wood canvases hang from the walls.

A “memorable” coming-out

Not long after she reunites with her mother, Cléo is asked to explain her identity. She remembers how her mother came into her room one evening and said, “ Listen, I would like to know if you are gay. If you are, I prefer that you tell me rather than I find out from someone else, and so that I know how to protect you.”

Cléo isn’t able to tell her the truth. “ I had prepared for her to also reject me,” she says, “ But in the end I decided to tell her and to get it over with, once and for all.” Half an hour later, she goes to her mother and tells her that no, she is not “a homosexual.”

“ Actually, I like boys and I feel better when I wear a dress.” Cléo pushes through strong emotions to recall her mother’s response: “ Me too, I also like boys and I like to wear dresses, you know.”

“ My coming-out was as simple as that,”Cléo says with a smile. “ I felt very good and relieved, even if there was some awkwardness in the weeks that followed. We didn’t know how to look at each other or how to talk about it.” It is her mother who brings up the subject again, this time by gently telling her that she can “ dress like a girl” if she wants to. “ We spoke about it more and she told me that she had wondered if I was transgender even when I was a kid. She told me that I never wanted to dress like a boy and that she would braid my hair.”

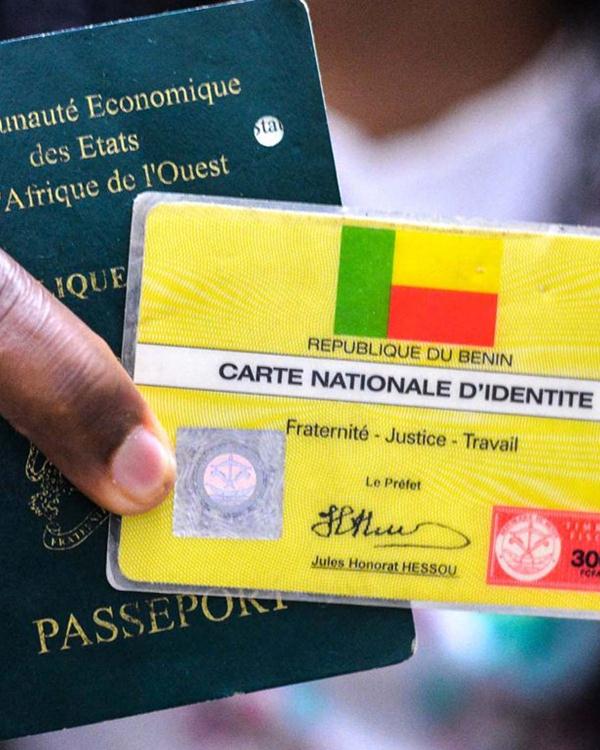

Cleo was only able to keep hold of two documents from Benin: her passport and identity card.

Activism in Benin

Cléo feels a certain level of protection from her mother, who is the eldest child from a “ fairly well-known and noble family.” “ I could stay in Benin for a while without really fearing anything because I was kind of ‘untouchable.’”So, she picks up her organizing for LGBT rights through various under-the-radar groups. As is the case in Tunisia, “ only some of the associations were registered with the state, but not to defend these [LGBT] rights,”she clarifies, they were “ [supposedly] for the prevention of AIDS or STDs, for example.”

One day Cléo meets an advisor to the French ambassador. The advisor says the embassy can support her mission, and he works with her to create a program that brings together civil society organisations fighting against homophobia. The platform was meant to enable gay and transgender people to meet and plan actions to support their collective agenda. The activists would also seek out participation from religious leaders, ministers, and journalists for their discussions on the situation of LGBT rights, a topic Cléo says is “taboo” in Benin. Eventually, they organize debates and open houses, but “ unfortunately, the support from the French embassy didn’t work for us; it reinforced the idea that LGBT rights are an imported concept imposed by Europe,” the young woman laments.

Through these activities, Cléo becomes a well-known figure and speaks publicly about being transgender. Her activism boosts her morale and makes her feel like she’s “ doing something” for her community. “ My mother’s protection and unconditional support encouraged me to speak publicly,” she says. “ She herself tried to start an organization for parents of gay and transgender children, but unfortunately it was a big flop!”

But being openly transgender in Benin is still risky. Cléo receives threats and is afraid of being reported to the police and of being subjected to the same treatment as other transgender people. They were “ stripped and filmed in public, sometimes by journalists for their so-called ‘scandal column.’”

She too knew what physical and psychological violence felt like. One time, an uncle on her mother’s side locked her up in a church for three days, without food or drink. The starvation was meant to “ exorcize the deep evil” from her. It was only after her mother demanded her release that Cléo is able to leave. But a few weeks later, she is locked up again, this time in the uncle’s house. “ I couldn’t go to university, and they confiscated my computer and telephone,” she says. “ Sometimes my uncle or a pastor would come to tell me that what I was doing was against nature, that I could not do this to my mother who had no other sons.” Cléo remains imprisoned there for almost a month.

The young woman’s fear begins to mount. “ One day I received a summons from the police accusing me of indecent assault. This was the final straw.” This offense is punishable by a fine and several years in prison. At this point, her mother realizes that Benin is no longer safe for her daughter and that her family’s status would no longer be enough to protect her. They decide to leave.

Scanning through Cléo’s passport, the word “departure” stands out on every page.

The escape

One night, Cléo and her mother flee the country, without telling anyone. They travel by bus. They can’t fly because her father works “ in air traffic” and “ would have immediately found out about my departure . . . he warned me that if he found me, he would ‘take me out’ for bringing shame to the family.” The two women cross through Togo and Ghana before arriving to Ivory Coast where they settle temporarily. The trip lasts only two days, but Cléo is exhausted. “ I was scared, I was stressed,” she confesses.

“In the rush of leaving, I could barely take anything with me. I am not materialistic, but I really felt like I had left everything behind.”

Despite the circumstances, some memories from the journey still make Cléo smile, like the night when Cléo and her mother were stopped by customs official at the border between Benin and Togo. One officer was thoroughly confused: “ He was completely thrown off, because he was under the impression that I was a woman, but in my passport it was written that I was a man. He kept me for half an hour, asked all of his colleagues for advice, and finally let me through, calling me his ‘girlfriend-boyfriend,’ ” she says laughing. “ We are still in touch, by the way.”

Once in Abidjan, the two women look into which country to move to so that Cléo could pursue a career in fashion. The bordering countries are quickly eliminated from the list. “ In West Africa, the repression against transgender people is the same everywhere,” she says, “ I would not have felt safe.”

Cléo applies to several fashion schools as “ far away as possible” from her country of origin. Figuring that life in France would be too expensive, she considers North Africa next, where she hears black gay communities are beginning to develop. Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia seem to be good alternatives.

“ A school in Tunisia responded to me. I received my visa within a week and I left for Tunis at the beginning of 2012,” she says matter-of-factly.

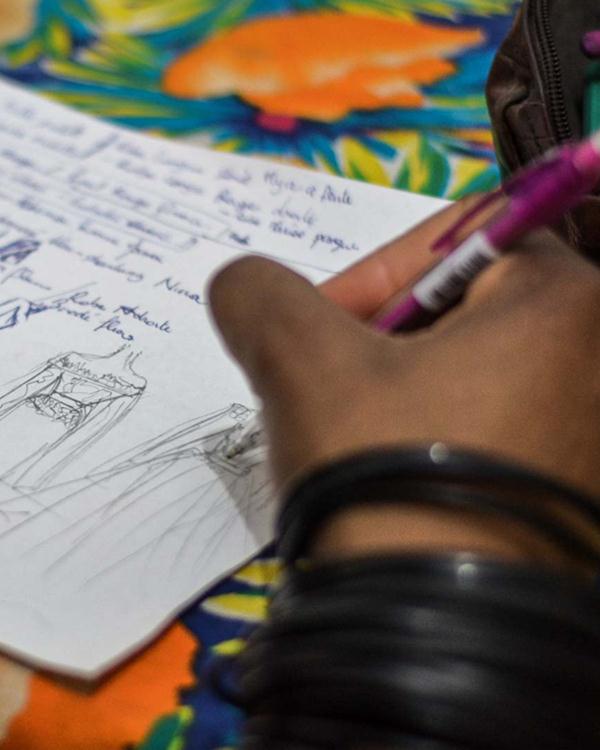

Cleo finishes off the sketch of a dress she plans to make soon.

A rough start in Tunisia

Cléo saw the move to Tunisia as an opportunity for a fresh start. “ But I became disenchanted very quickly,” she says in a low voice. “ As soon as I arrived, I had to sign a document saying that I was not allowed to work in Tunisia, contrary to what the school told me.” However, the young woman decides to stay, convinced that she can find a way to support herself.

During the next two and a half years, Cléo lives mainly off of her and her mother’s savings. “ Between the school fees, transportation costs, and food, I ended up being short on money and in a precarious situation.” When her visa expires, she lives in constant fear of being deported back to Benin, where she has no support (her mother having left as well). All it would take was one police check to send her back. Cléo feels helpless and describes this period as “ extremely difficult and distressing.”

In addition to the financial and administrative difficulties, Cléo faces multiple forms of discrimination.

“ Tunisia is a beautiful country, I feel that I have integrated will, I have Tunisian friends . . . but I am also aware that people can have a negative perception of black women,” she says. “ Sexual harassment is widespread and I wasn’t prepared to face that.”

The young woman adapts her daily routines to avoid returning home late, and she takes taxis instead of public transportation to limit the potential for harassment. She was even humiliated by Tunisian doctors to whom she went for hormonal treatment. “ When they were not moralistic, they were very dismissive, even violent in their remarks. One of them told me I was crazy and that I should seek treatment . . . crazy he said.” Others prescribed her drugs, but didn’t want to conduct follow-ups and told her to manage herself, “ which is very dangerous on these treatments. They don’t even bother to adjust the dosages!” she says.

In light of these problems, a Tunisian friend suggests that Cléo apply for asylum. “ She had heard about the procedure for people like me,” says Cléo. “ At first I didn’t know who to contact or how it works. Thanks to information that I found on the internet, I applied for a tourist visa to France, hoping that once there, I could seek asylum.” But the visa is denied. And so Cléo stays in Tunisia and continues to do some research. In 2013, she lands upon the contact for the Maison du Droit et des Migrations (House of Rights and Migration). This organization helps her in preparing and submitting a file with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the only organization able to grant refugee status in Tunisia. Cléo is granted refugee status in 2015.

Although Tunisia ratified the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, which entails granting asylum to refugees, allowing them to work, and providing access to health and education, there is no national law protecting refugees nor a national authority to process asylum applications.

In this context, the UNHCR, in partnership with the Tunisian Red Crescent, processes applications and grants refugee status in accordance with international law, which provides a minimal level of protection for these asylum seekers.

Cléo prefers to make clothes from her own designs, but she also works with articles of clothing that people bring to her for modifications, like this blazer.

New perspectives

Cléo’s refugee status comes as a big relief. “ The pressure has decreased,” she says with a smile. For Cléo, to have refugee status means to have “ the promise of a future.” “ I receive financial aid from the UNHCR, which allows me to live a decent life. They give me medicine, blankets, food,” she lists. This new status provides her with “ stability.” Her status as an “irregular migrant,” which is fineable up to 1,500 Tunisian dinars, is cleared. Cléo is also seeing a psychologist, and the sessions are helping her to work through trauma from the persecutions she has experienced. “ I am making progress, even though there are still some dark things that I am not able to bring up yet,” she reveals.

This newfound stability has enabled Cléo to open up a sewing workshop, something that she has dreamed of doing for ages. But getting started was difficult. “ During the first two months, I was exploited by a woman who paid me 50 dinars for wedding dresses. I didn’t have any source of income and it was the only work that was offered to me.” The House of Rights and Migration advised her to stop accepting these rates and even supported her project financially. “ At the moment, I design and create dresses in partnership with three Tunisian fashion houses. I also organized a fashion show,” Cléo says enthusiastically. “ I hope to make a name for myself in the industry.” She currently accepts all types of orders, but she aims to one day specialize in haute couture and embroidery.

Small colored drawings showcase Cléo’s vision for her haute couture collection.

“Sometimes, I have regrets”

Cléo never imagined that her life would unfold like this: “ When I think about it, I tell myself that I had a future set up for me, and that if I had never been an activist, none of this would have happened.”

Looking back, Cléo considers her activism through a critical lens; she doesn’t think her activism had any effect on LGBT rights in Benin. " Maybe it could have had an effect, if stripping transgender people in public already disturbed people. But this is not the case today,” says Cléo, “ and no one speaks about it.”

According to her, the first step is for mentalities to change: “ Maybe in 10 years?” The former activist is pessimistic about the treatment of transgender people improving in West Africa, and the whole continent at large. She finds that the situation for the LGBT community in Tunisia is better than in Benin, even though the subject remains mostly hidden in society. “ But this is already better than the public humiliations. To be hidden is a protection of sorts,” she says, dispirited.

She adds that although the debate on homosexuality is gaining ground, transgender people are still marginalized and left out of the conversation for LGBT rights, both in the West and in Africa. According to her, it will take time for the transgender community to be taken into consideration and accepted by society.

“ Today, I am tired, I want to rest, to live a peaceful life. But if I resume my activism one day, I will focus on the rights of transgender people and not on the LGBT community as a whole.”

Cléo sometimes feels bitter about her personal experiences. “ I think that my struggle cost me a lot and sometimes I regret it a little. My family is divided because of this, and my mother still receives threats from members of her own family. One of my uncles even threatened to burn her if she didn’t reveal where I was.” Cléo feels guilty about the position that her mother is in, but she doesn’t know how to remedy the situation. She thought about bringing her mother to live in Tunisia but quickly abandoned the idea. “ Her whole life is there,” she says, “ at 58 years old, with her fragile health, she doesn’t have the strength to start anew. Sometimes, I tell myself that if I wasn’t what I was, life would be a lot simpler.”

Cléo pauses before continuing with her story. She says that despite everything, her fight was not “ a silly thing.”

“ I needed for all of this to get out and it did. But if I could go back, with the knowledge that I have today . . . I think that I would not do it again. Because of this, I cannot go back home.”

The only way that she could go back to her country would be if she obtained another nationality, but she doesn’t count on this happening and says “ when you flee your country, you cannot return.”

Cléo is at peace with how distanced she is from the family that rejected and harassed her. ” They live their lives, and I live mine. I took the surname of my maternal grandmother to really cut ties with them. We simply took different roads,” she says.

Cléo does not yet know what her long-term plans are. The UNHCR does not consider that Tunisia is a stable country for her because of “ discrimination based on race or sexuality.” She is in the process of being relocated, and she recently found out that she is meant to leave to Europe soon. She doesn’t know yet where exactly she will live, but she does know that she will receive a residency permit, accommodation, and protection: a new promise for the future.