Preparations for the first of June

In Tunisia, preparations for Bourguiba's return were in full swing. The Destour youth and the various sections of the Tunisian scouts were organising the event, headed by Azouz Rebaï, a Neo-Destour executive. On the eve of June 1st, the agenda was already set and all the stages of the procession were planned according to a rigorous programme.

In order to prepare for all eventualities, the security of the convoy was ensured. Intelligence reports indicated that members of the Old Destour party or those of the French Presence group could be orchestrating the assassination of the Neo-Destour president.

"The Neo-Destour is said to have organised a vigilant police force including, in particular, some former fellaghas." (Note from May 9, 1955)

"In nationalist circles, reference is made to a personal guard for Bourguiba to ensure his safety, while the other members of the political bureau are said to have a collective guard.” (Note from May 31, 1955)

The security of the public was also ensured since the members of the party had set up various rescue centres for the crowd at different locations along the procession route, such as La Goulette, El Kram, Tunis and Bab Souika.

In order to ensure the success of Bourguiba's journey across the 25 km route, the Neo-Destour party set up an internal security service consisting of 20,000 members of the Destourian youth and scouts. The groups were divided into units, each of which was responsible for keeping its own members in order.

In parallel to this security service, the colonial police force was made up of 2,000 uniformed and civilian policemen and 6,000 soldiers who were supposed to accompany the procession from afar, and leave the Destourian security service in charge of operations. It was a compromise arranged by Taïeb Mhiri, director of the Néo-Destour party, who had negotiated the route and claimed full responsibility for the event from the French authorities.

On May 31, Habib Bourguiba arrived at the Gare Saint-Charles in Marseille, on his way to the port to board the ship 'Ville d'Alger' that was bound for Tunis. According to the information sheets of the officers on board, he was accompanied by his son Habib Jr, some members of the Neo-Destour (including Mongi Slim and Ahmed Tlili) and several journalists from Europe and the United States. The president of the party was greeted by Tunisians on the quay, singing the song 'Namoutou'*. During the crossing, Bourguiba gave interviews to the international media and took pleasure in being photographed.

The arrival at La Goulette

Tunisian National Archives

When the ship arrived at La Goulette, it found itself surrounded by fishing boats from various Tunisian coastal regions. Among them was the one that Bourguiba had clandestinely used to leave for Libya from the Kerkennah Islands with the help of some fishermen in March 1945. On board the boat, a troupe was playing Kerkennian music.

The ship 'Ville d'Alger' docked at 10 a.m. at the port of La Goulette. "Dressed in European-style navy blue and sporting a fez", Bourguiba held a white handkerchief in one hand and a pair of binoculars in the other (La Presse, June 2, 1955). The many other travellers on board the ship, who were not part of the delegation, went completely unnoticed.

The large crowd of people who had come by train, bus, car or on foot were all waiting for Bourguiba along the platforms. The party leader was welcomed by several public figures. Princess Aïcha, daughter of the reigning bey 'Lamine Bey', welcomed him on the bridge. When he set foot on land, he was immediately carried by members of the fellaghas and the Destourian Youth. In response to the very vast presence of scouts, Bourguiba gave a characteristic salute and wrapped a red scarf around his neck.

He was then directed to make his first speech in a reception hall set up in a port hangar for the occasion. Several public figures attended the event: the Chief Rabbi of Tunisia; Charles Haddad, president of the ‘Israelite’ community of Tunis; the fellagha leaders Sassi Lassoued and Lazhar Chraïti; the Hanafi sheikh and the Malekite sheikh; professors from the Zitouna; delegations from the UGTT with banners saying "the UGTT welcomes the return of the supreme fighter"...

The French press also noted the female presence, albeit with an orientalist bias:

"Alongside the young men, young girls who are dressed in either a white dress with a red scarf, or in a white blouse with a red skirt, have taken their seats. Princess Aisha [...] is at the head of a group of young girls carrying beautiful flower bouquets. It is noteworthy that all the women and girls are fully unveiled. The widows of Farhat Hached and Hedi Chaker, accompanied by their children, are seated among the public figures." (La Presse, June 2, 1955).

As can be seen from the video footage of the day*, Habib Bourguiba then headed to the Beylical Palace in Carthage [now Beït al-Hikma] to greet the ruler Lamine Bey, who decorated him with the 'Ahd al Aman' badge [a beylical decoration celebrating the foundational pact of 1857].

The route to Tunis

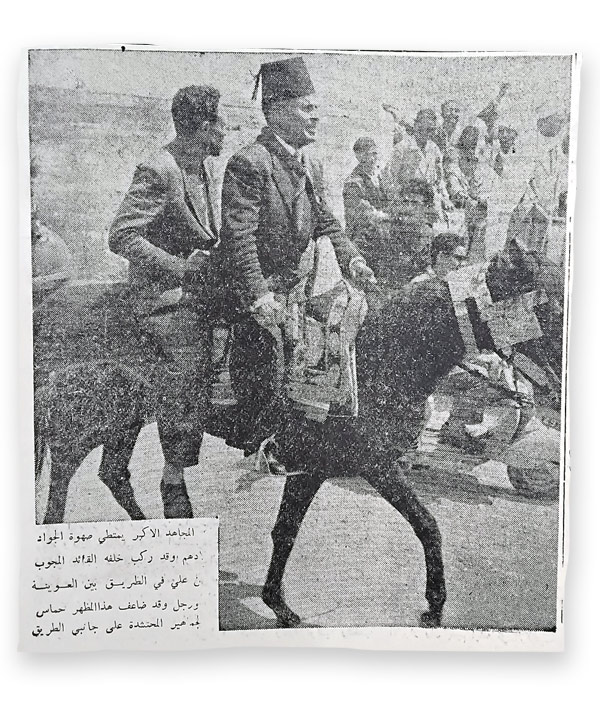

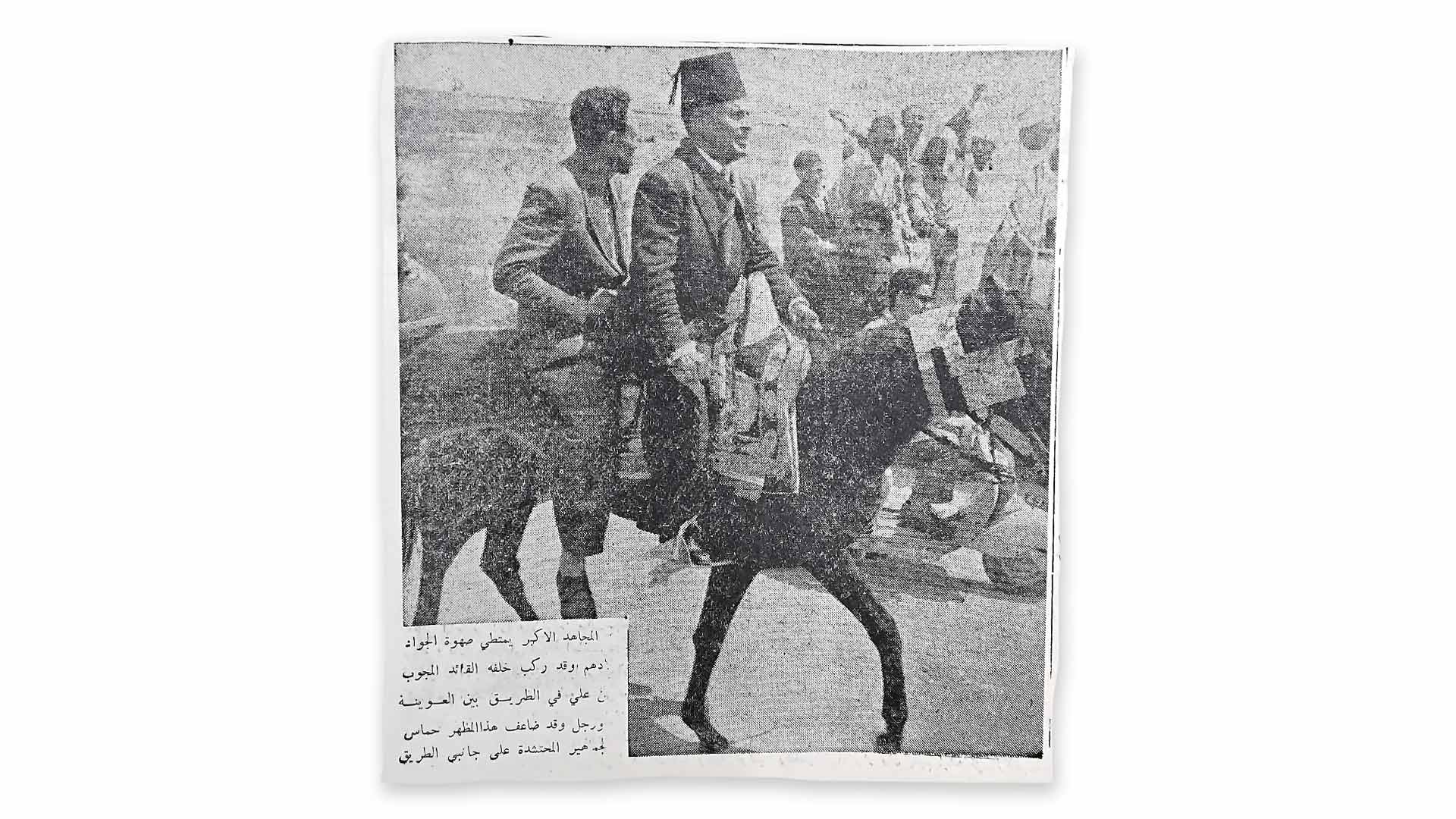

From Carthage, the convoy headed towards Tunis. A cavalry unit, formed by the Fellagha Jlass militants from Kairouan and led by Lajimi Ben Mabrouk, escorted the car from which Bourguiba greeted the crowd. When he arrived at L'Aouina, he climbed onto a thoroughbred horse provided by the Jlass cavalry. Bourguibe mounted his horse with easy thanks to the riding lessons "that the President of the Council, Edgar Faure, had organised for him in Paris under utmost secrecy, in the middle of negotiations"*.

Tunisian National Archives

Sitting behind Bourguiba, one could make out the silhouette of Mahjoub Ben Ali, a fellagha leader who acted either as a bodyguard, or as a helping hand with the horse during the ride, sources do not specify which. The cavalry chief Jlass handed a feathered hat (typical to the Kairouan region) to the leader, who gladly wore it.

Upon arriving at Bourgel, Bourguiba disembarked from his horse and continued by car as the convoy headed to the house of his wife Mathilde, before heading to his former house in the medina. The end of the procession took place at his residence at Place aux Moutons (which had already been renamed "Leader's Square" [Ma'qal az-Zaïm]), his former neighbourhood thus intertwining with this historic moment. A large crowd, singing 'Namoutou', waited for him by the stage where he held a second speech* intended to reassure the French population in Tunisia, and to call for unity.

Tunisian National Archives

The official security service did not intervene much during the festivities. According to the media, the French police only arrived to "restore the situation at the top of the Porte de France, where the Tunisian flag had momentarily replaced the French tricolour flag, which finally mounted the same flagpole" (La Presse, June 2, 1955). Deploring this 'attack on urban aesthetics', the newspaper also referred to the arrests of young Tunisians who had cut down palm trees on Avenue Gambetta [now Avenue Mohamed V] in order to build triumphal arches.

However, the security service was keeping a close watch on the main route through the city, Avenue Jules Ferry [now Avenue Habib Bourguiba], where the General Residence was located. "Pickets of mobile gendarmes and soldiers, radio vehicles, trucks loaded with rolls of barbed wire in case of disorder, and automatic rifles at Porte de France"...

The newspaper reported on a few incidents, such as a 14-year-old boy who was clinging to a TGM carriagem and whose leg was severed as he fell onto the tracks; the awning of the Sidi Mahrez mosque which collapsed under the weight of the demonstrators; a man clinging to a truck, and whose legs were crushed by a car; and a young man clinging to the ladder at the back of a bus, who fell off in motion and was severely wounded and later hospitalised.

Due to the organisation and huge turnout, the day was considered a success by other newspapers and the Neo-Destour leaders, despite these events. The number of people attending from all regions was estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands. The Tunisian shops were all closed. Only those run by Europeans remained open, and the Tunisians who worked in them all got the day off. Several children were absent from school for fear of disorder on the European side, or in order to participate in the festivities on the Tunisian side.

The end of the day was marked by lively musical performances in the areas of Bab el Khadhra, Bab Souika and Bab Mnara. As for the European side, "things returned to their everyday tranquillity around 19h". (La Presse, June 2, 1955).

Despite the resounding enthusiasm of several newspapers describing the event as "unprecedented", "exceptional", "successful", and "an atmosphere of jubilation and elation" and "of sacred union", discordant voices could also be heard. Beyond French political forces (such as the 'Rassemblement français de Tunisie' party, which protested against endangering the French presence in Tunisia) the Tunisian Communist Party also criticised the internal autonomy agreements, pointing to the threat to Tunisian national sovereignty. In criticising co-sovereignty, the party cautioned against maintaining civil controls, a tied-up Tunisian economy and a permanent link between Tunisia and France.

Indeed, "in a certain number of strategic sectors such as the police force, the justice system, large parts of the economy, not to mention diplomacy and the army [...], Tunisian autonomy remains limited or even non-existent".* Within the Neo-Destour party, adopting the internal autonomy agreements was to trigger a violent conflict between Bourguiba's followers and Ben Youssef's supporters.

The path to domestic autonomy

The seeds of the discordance were sown during the absence of the party president Habib Bourguiba when the secretary general Salah Ben Youssef took a leading role in the early negotiations for independence.

From 1945 to 1952, Bourguiba led international mobilisation campaigns on the Tunisian colonial question from Egypt and the United States. Confronted with France blocking the negotiations, the anti-colonial armed struggle intensified.

"Since January 18, 1952, [...] the Neo-Destour, the national unions, the scouts and the Fellaghas have all been involved in [the] armed struggle. In addition to competing with the ambition of the colonising power to exert a monopoly of violence on Tunisian territory, they challenged their economic and political interests as well as those of their local allies. Indeed, they multiplied attacks against the French armed forces, as well as assassinations and targeted attacks against colonialists and Tunisians close to colonial authorities. They also target the French economic infrastructure through acts of sabotage."

- Khansa Ben Tarjem, 'Ouvrir la boîte noire : appareil sécuritaire et changement de régime' [Opening the black box: security apparatus and regime change], Tunisia. 'Une démocratisation au-dessus de tout soupçon?' [A democratisation above suspicion?], Vincent Geisser, Amin Allal (eds.), Paris, CNRS, 2018, p.232. Accessible here. (Fr)

Upon his return to Tunisia, Habib Bourguiba was arrested in January 1952 and transferred to Tabarka and subsequently to Rémada before being moved to the island of Galite in May of the same year. Two years later, he was transferred to France, on the island of Groix, still with the intention of keeping him out of trouble. The President of the Council, Pierre Mendès-France, had him transferred to the Château de La Ferté in Amilly (110 km from Paris) on July 21, 1954, in order to prepare for the coming negotiations.

By the end of May, Bourguiba is impatient to return, but the colonial authorities try to convince him to delay his return because of the tensions in the Tunisian regency. He is finally authorised to return to Tunis and invites Ben Youssef to return with him, but the latter refuses and stays in Cairo.

Writing History

In fact, the pomp and circumstance of Bourguiba's parade on June 1, 1955 left little room for any questioning of the domestic autonomy agreements. The very fact that he chose to return before the official signing of the agreements on June 3 was significant. By returning immediately after having 'won' the negotiations, Habib Bourguiba made this day his own. No other institutional or official event tainted the heroism that he embodied. Not being a member of the government and unable to sign agreements (given his limited status as party president), he orchestrated his own coronation. By calling him the "Supreme Fighter" [ al moujâhid al akbar] and the "Lord of the Free" [sayyid al-ahrâr], the newspapers thus contributed to forging the myth of a saviour who had offered freedom to an entire nation.

The controlled imagery and attention to detail surrounding his return suggest that Habib Bourguiba and the members of the party who were loyal to him had conceived this event to be a moment of posterity. In his speech following his arrival at the port of La Goulette, Bourguiba announced that it was a "memorable day". The 1st of June thus seems to be a day conceived and executed to be a potential historical memory. The Neo-Destour president paternalistically declared before the crowd that day that "there is a maxim and a lesson to be deduced from this memorable day, which might serve you until the end of your days and for all eternity".

In order to write this victorious and unchanging history, the Neo-Destour party and their leader Bourguiba manipulated the public memory.

Firstly, erase all rivalling symbols of the past

In July 1937, Sheikh Thâlbi, founder of the Destour party, returned to Tunisia after many years in exile. He disembarked at La Goulette, waving a blue handkerchief. The leader of the dissident Neo-Destour party was waiting for him at the bottom of the ramp.

"He was so impressed by the image that he wanted to recreate it himself when the time came, [but] not without perfecting it. In 1955 he rode majestically through the crowd as an accomplished horseman. For the 'Supreme Fighter', there was no room for two providential men at the same time. Bourguiba thought that Thâlbi would join the Neo-Destour and accept his leader, [but] when this did not happen, he derailed the planned conciliation meeting between the delegations of the 'Old' and the 'Neo-Destour' [...]."

- T. Belkhodja, ‘Les trois décennies Bourguiba’ [The three decades of Bourguiba], p.12.

Thus, by being the leader of the Neo-Destour (as opposed to the Old Destour), and by setting himself up as the only nationalist militant, Bourguiba relegated Thâlbi to oblivion by recreating his return and amplifying it, thus rendering him obsolete.

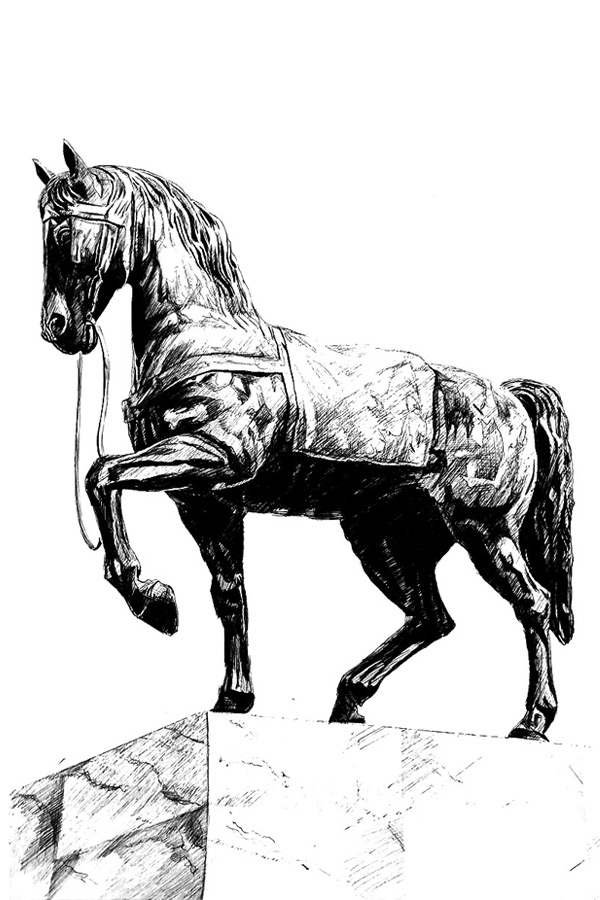

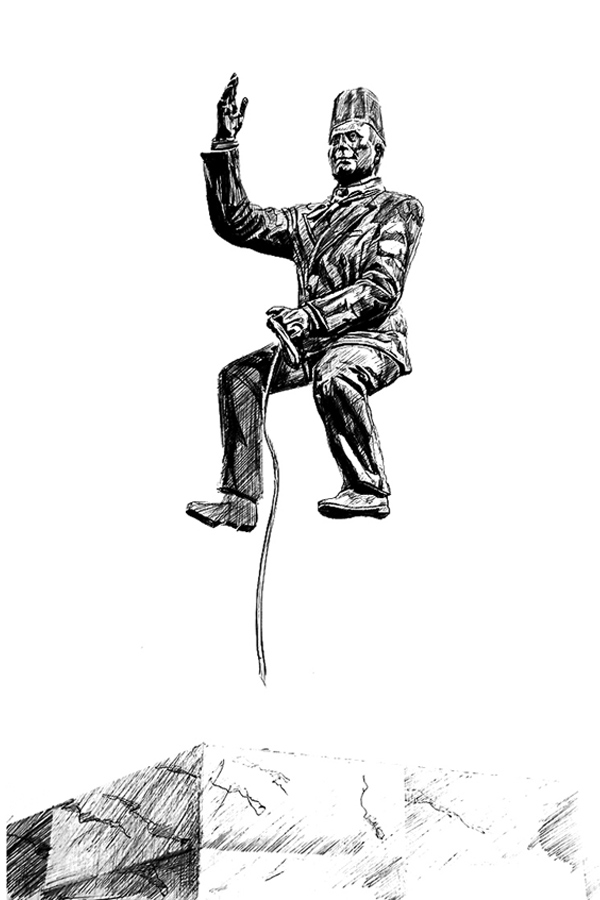

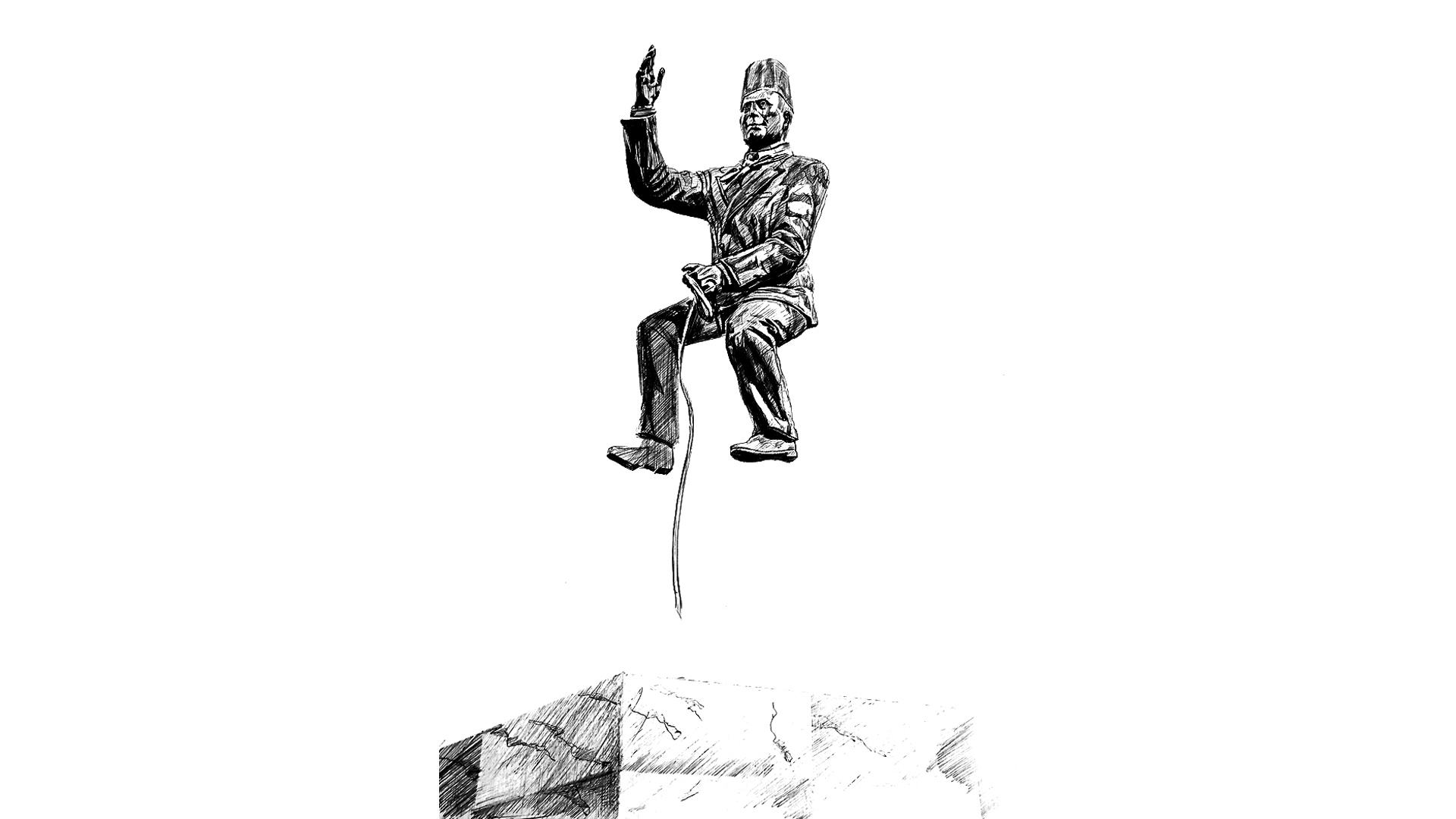

The figure of Bourguiba mounted on a horse did not merely erode the memory of Sheikh Thâlbi, but also attacked the notion of urban colonial symbolism. In 1976, an equestrian statue of the president was placed at the end of the former Avenue Jules Ferry, renamed Avenue Habib Bourguiba following independence. Just like with the name of the avenue, the Bourguiba's statue replaced the statue of the former colonial administrator Ferry, which was taken down after independence.

Original work for this article by the artist Atef Maatallah

Secondly, develop new symbols

The towering bronze statue that commemorates the 1st of June corresponds to a semi-fictional imagery since Habib Bourguiba was in fact not alone on his horse, but closely accompanied by his bodyguard Mahjoub Ben Ali. The statue thus seems to capture a moment that never really occurred, but through performative action, the myth is transformed into reality.

Its creator, sculptor Hechmi Marzouk (born in 1940), carried out several commissioned statues of Bourguiba in connection with the 1st of June (whether of return or of exile), including two equestrian statues in Tunis and Monastir*.

These two statues both portray the moment when Bourguiba rides his horse on his way to Tunis, the first one depicting him with a fez on his head, and the second one with the Kairouanese hat. In 1975, after having been named the winner of the competition to create the equestrian statue in Tunis, Hechmi Marzouk threw himself into the creation of his initial model for six months, but not without the intervention of a ministerial commission requiring the representation of a purebred Arab horse and the reproduction of photographs from June 1. Bourguiba wished to monitor the progress of the work based on the memory of the sculptor who was contacted in this regard:

"Bourguiba often visited me at the L'Aouina studio, which was a hangar for planes. He loved coming to see his statue. He would make remarks about the saddle being too low or ask me not to forget the fez on his head. He would stay for half an hour each time and we ended up becoming friends. He wanted me to portray his happiness on the first of June, a 'different feeling' as he put it. He wanted the statue to express all the emotion that he felt that day. In the end, he was very happy with the result", says the sculptor.

Hechmi Marzouk also recalls the pressure he felt in the face of the complexity of the task: to record and depict a historical moment. He did not hesitate to smash and reshape an entire part of the structure after a few months of work, in order to make the horse look "prouder", in his words. "I made the bust more prominent, I had to show that it was a thoroughbred, with a raised head, proud to be carrying the president, with all the nobility that he is due", he recalls. The sculptor wanted to convey this chivalrous grandeur through the front leg of the steed, which is raised, representing, according to him, the political character of the statue, and not a warlike character, which would have been conveyed with all four legs fixed to the ground.

Original work for this article by the artist Atef Maatallah.

Finally, become one with the nation

During the procession on June 1, the attendance of delegations representing various Tunisian regions contributed to the narrative of national cohesion around a single man, and further fed into the rhetoric of the providential hero. During the ceremony of Bourguiba's return, the convergence of the various regions was achieved through the representation of their respective 'folklores', such as the Jlass cavalry or the music of the Kerkennah Islands. In addition to the geographical dimension, a political aspect was also incorporated into this representation of the union. Indeed, several groups were present: from the scouts to the teachers of the Zitouna, including the beylical family and the fellaghas. The event also brought representatives of the country's religious communities together.

During the homecoming spectacle, everything was designed to show that the entire nation was gathering for Bourguiba, and that he himself was assimilating through greeting them. Bourguiba incorporated national elements such as wearing a fez (a symbol of belonging to the elite), then swapping it for the hat of the Jlass (a symbol of chieftaincy), as well as riding a purebred Arab horse and wrapping a scout scarf around his neck, thus making the body of the future Tunisian president "assimilated", and establishing a national identity in the same process.

All the symbolic and material components of a national identity construction were there*: the future national anthem, the flag, the territory outlined and represented by the regional delegations, the folklore, the image of a united people... All that was missing was a founding event for the national narrative. It would be the return of the hero.

This return to the country thus acted as a double representation of the nation through the simultaneous construction of both the united people as well as their 'zaïm' [leader]. Carried by national liberation fighters upon his arrival, seen in the midst of all the fluttering Tunisian flags, Bourguiba embodied national unity, within the framework of the production of course.

By incorporating the diversity of national symbols and giving shape to the nation on this day, Bourguiba was established as a legitimate figure of independence. The day after independence, June 1, was known as 'Victory Day' and became a national holiday until the rise of Ben Ali who abolished it. The Tunisian national narrative is thus entangled with the story of Bourguiba's personal life.

However, even if there was less than absolute cohesion around the domestic autonomy agreements, dissonance was not possible. The discordant voices that had aspired to a more radical independence were thus engulfed by a national project with a devouring appetite.