I had finally arrived at the right place, nearly two years after first setting out to claim Tunisian citizenship and just a couple of months after joining the Inkyfada team. In the doorway, where I was asked to remain for lack of space, I cradled a collection of family documents amassed over many months, simultaneously hoping and fearing that they would make it into one of their piles.

Only ten minutes later, my reception hurried along by a looming administrative lunchbreak, I was whisked out of the building and given a post-it note receipt in exchange for the folder I had arrived with. I was told to expect a call when the document that would proclaim my right to Tunisian citizenship was ready. Six weeks later, I received the certificate of nationality. I felt relieved and quickly took the next step to get a Tunisian birth certificate: the essential proof of citizenship. However, at the time of this article’s publication, more than five months after submitting my file, my paperwork is once again in limbo.

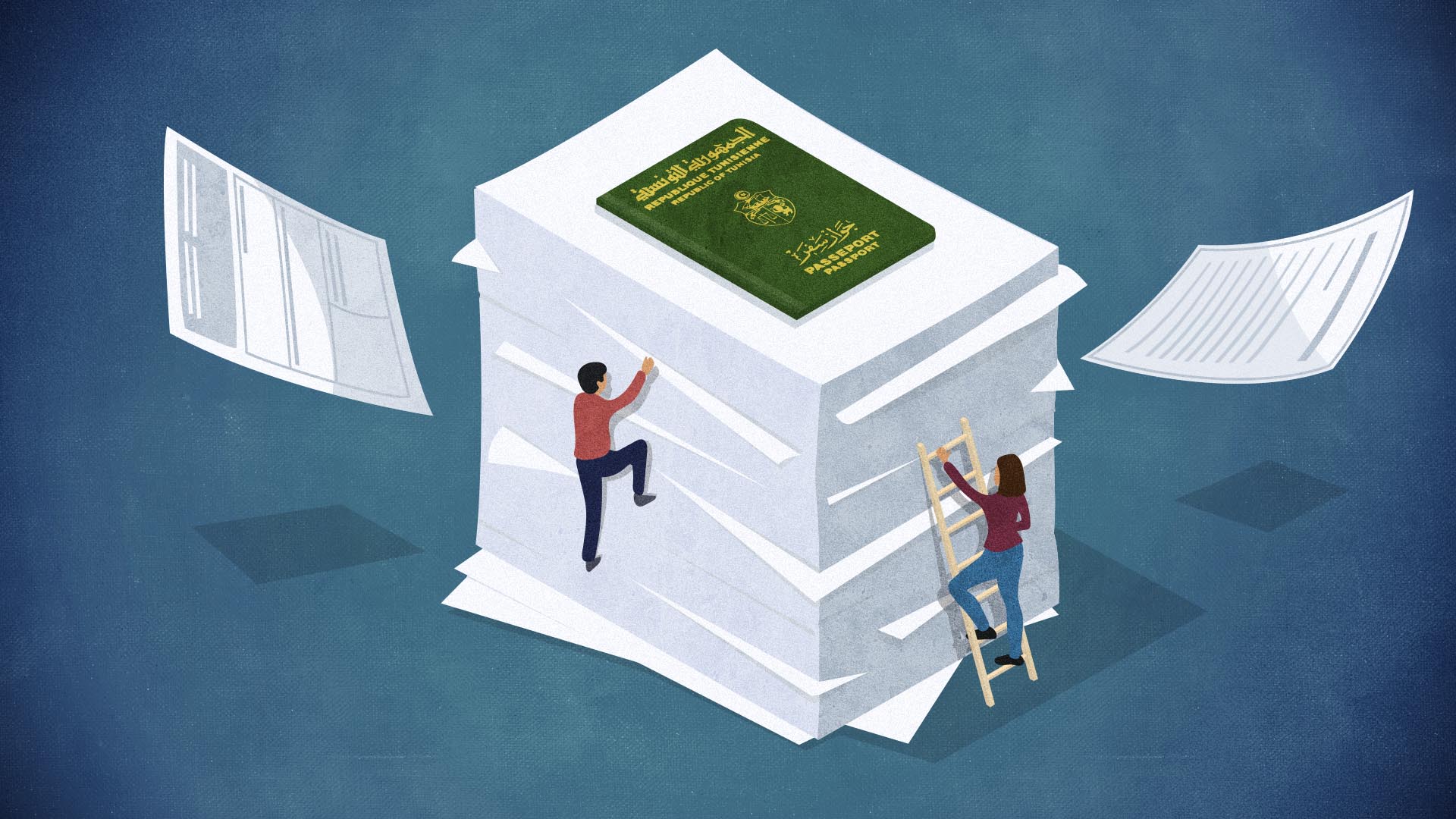

I am far from being the only one to have gotten lost in the maze-like diversions of claiming Tunisian citizenship as an adult. Rights are not clearly outlined, few legal deadlines exist, and very little reliable information exists online. For the individuals abandoned to fend for themselves in the opaque and - often insurmountably - challenging system of claiming Tunisian citizenship as an adult, Inkyfada has gathered insights in the hopes of providing pathways forward.

The New “Tunisian by Origin”

“The whole notion of ‘of course you’re Tunisian!’ rings false in my head,” says Zaina*, 24, a neuroscience graduate living in California and the first in her Tunisian lineage to be born abroad.

As the foreign-born daughter of a Tunisian mother and a non-Tunisian father, Zaina’s skepticism is perfectly justified. Until December 2010, when the soon-to-be-toppled government reformed the Tunisian Nationality Code and afforded Tunisian women the right to independently pass down their nationality,** Zaina had not been considered “Tunisian by Origin,” meaning she did not possess a guaranteed right to Tunisian citizenship. She knew this to be true, having witnessed her parents’ attempts to register her and her brother at the Tunisian embassy in the US, years before the 2010 reform.

Following the failure of these attempts, Zaina has lived with two conflicting understandings. On the one hand, she feels a deep sense of belonging to the country, nourished by many summers spent in Siliana with her extended family, who are well-known in the region, in part, for her “larger-than-life” grandfather who played on the Tunisian National Football team that made it to the ‘78 World Cup. On the other hand, she says that she carries with her “the feeling of not being enough for the nationality”… as if the government had told her to “stay away.”

This cognitive dissonance, Zaina says, “has manifested differently and grown over time, especially after losing my mother and filling the role she had in the family.”

It wasn’t until late 2019, over a long-distance phone call with Inkyfada, that Zaina learned of the 2010 reform to the Nationality Code. In principle, the reform’s new definition of “Tunisian by Origin” was a step towards clarity and justice, yet, for a growing population of the Tunisian diaspora, many barriers remain on the path to claiming citizenship: ambiguity and persistent discrimination in the Code’s text; an uncodified and costly system for people over the age of 18; and a lack of reliable, publically accessible information.

“It’s tragically ironic,” Zaina says, that neither she nor her mother were informed of her new status in 2010. Her mother passed away that same year, when Zaina was only 15 years old. Now an adult, Zaina must navigate a much more complicated procedure to claim the citizenship her mother sought to pass down to her. Without anywhere to look for guidance, she is questioning, mournfully, whether she can maintain a connection to her motherland.

"I can feel that my relationship to Tunisia is at a critical point right now, where if I don’t actively do something about [my citizenship], it could just slip away,” Zaina admits.

One Less Barrier for Tunisian Mothers

The text of the Nationality Code that is currently in effect was originally promulgated shortly before the 1956 independence and has been amended by the Tunisian parliament several times since. Most significantly, Article 6, which grants the inalienable right to citizenship through descent, was amended in 2010, resulting in Tunisian mothers acquiring, for the first time, the right to automatically confer Tunisian citizenship to their children. At the same time, Article 12 was repealed altogether. This article described nationality declarations (what was essentially an application process) for the foreign-born children of a Tunisian mother and non-Tunisian father.

Before it was invalidated in 2010, the process to acquire citizenship through Article 12 - called a “ joint declaration” - worked against Tunisian women in several ways. According to the article, this declaration required Tunisian women to involve their non-Tunisian husbands in the process. It wasn’t until 2002 that the Tunisian government made an exception for Tunisian women whose non-Tunisian husbands had "died, disappeared, or become legally incapacitated,” in which case they were able to independently submit this declaration on behalf of their children.

Moreover, between 1973 and 2017, a circulaire issued by the Ministry of Interior prevented Tunisian women from registering their marriages to non-Muslim men within Tunisian civil registers. In place until former-President Essebsi overturned it in 2017, this circulaire - although technically not a law - empowered civil officers to deny marriage certificates to Tunisian women in interfaith couples, unless the non-Muslim partner were to officially convert to Islam.

As a result of Access to Information requests submitted in March 2020 by Inkyfada, the Ministry of Justice released data on June 18 on the rate of Tunisian women who submitted nationality declarations for their children born abroad to non-Tunisian fathers. The data shows a significant increase over nearly five decades, during which the declaration process stipulated in Article 12 was modified several times before being repealed altogether in 2010.

Embassies as Gatekeepers

As a result of the reform, all Tunisian mothers and fathers living abroad now follow the same procedure to pass down Tunisian citizenship to their children: get in contact with the embassy closest to where the child was born, procure them a Tunisian birth certificate, and verify that it has been properly transferred from the embassy into the Tunisian civil registration system.

Although this procedure is well-documented and, in theory, straightforward, Tunisians living abroad report obstructionist practices in embassies that threaten to bring time-sensitive nationality procedures to a halt. Moreover, many Tunisian parents living abroad are not made aware that once their child reaches the age of 18, they will be required to navigate a decentralized process from within Tunisia that, without any legal deadlines binding it, can take months if not years to produce a result.

“I had heard multiple stories where people do everything they have to do and their kids aren't registered,” explains Nidhal, a business professor in Michigan, USA, who claims his two American-born children wouldn’t be Tunisian citizens if he hadn’t relentlessly followed up with the Tunisian embassy in D.C. over four years.

Shielded by anonymity and distance, “they deliberately try to push [you] away,” he says, recalling hostile questions he received from nameless officials, such as “Where did you get these kids from?” and “Why do they even need Tunisian papers?” He recounts that between 2014 and 2018, embassy staff tried on multiple occasions to refuse him service, overcharged him with expensive stamps and envelopes that were never returned to him, and, most significantly, misprocessed and lied about the status of his children’s Tunisian birth certificates. Following his own investigation, he discovered that the certificates the embassy had issued had not been correctly transferred to Tunisia and transcribed in the nation’s central civil registers.

“Imagine if I hadn’t followed up. They decide to go back to Tunisia, discover they’re not technically citizens, and have to face these administrative issues. I wouldn't blame them if they gave up, but also I feared for how lacking these papers could strain their relationship and one day their own children's relationship with the country,” says Nidhal.

One example of a parent who wasn’t able to successfully register a child is my own father, Khaled. In the early nineties, he was only able to register his first-born, my older brother, with the closest Tunisian embassy, in the Hague. For my file, a couple years later, he summarizes what he recalls quickly became an emotionally taxing journey: “I was always told that your nationality paperwork was underway, [the embassy officials] were unreachable for months and months, and then we moved countries, and life got in the way.” After arriving in the US in the mid-nineties, the embassy in the US said they couldn’t help and that he’d have to proceed with the embassy in the Hague. “I had no idea things would get so complicated once you turned 18,” Khaled admits.

In an effort to corroborate the accounts of embassy officials’ negligence, Inkyfada called the Tunisian embassy in D.C. in November 2019 to inquire about how to claim Tunisian citizenship once over the age of 18. In an extremely rushed WhatsApp call, the first secretary of the embassy, Sami Ben Nsira, suggested calling a colleague in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tunis, who, he claimed, is “in charge of Americans.” Asked if information was available online, he answered, “There are some websites, I don’t have an idea now, but I’m going to do some research and send you by email next week.” Despite following up on multiple occasions, the representative never sent his colleague’s number nor provided further information about the process.***

“A Foreigner in My Own Country”

Even from within the country, many non-citizen members of the Tunisian diaspora struggle to find the information necessary to navigate nationality procedures. Required to leave the country every 3 - 4 months (depending on their nationality) or pay a fine for every week they overstay their legal stay, these individuals report mixed feelings about being confined to tourist status in Tunisia.

Some of them are content - for the time being - with staying in this position, citizenship coming second to a feeling of belonging. “What really matters to me, [more than the passport], is to have a Tunisian life,” says Mari*, 29, a freelance journalist based between her mother and father’s respective homelands in Tunisia and France. She has heard that it’s very challenging to claim Tunisian citizenship after turning 18: a friend of hers born to a Tunisian father and Tunisian mother had successfully managed, but his sister, for a reason unknown to Mari, had not.

Others are actively searching for how to claim their citizenship and establish permanent residency in Tunisia. "It doesn’t seem like anyone thinks this is a problem,” says Inès, 21, who recently moved to Tunisia from France, referring to the general lack of information available for people like her “trying to not feel like a foreigner in [their] own country.” She reports receiving contradictory advice, even from friends who work in the Tunisian administration, and finding out-of-date information on government websites, such as the forms provided by the Ministry of Justice that date to before the 2010 reform.

“It’s true that the information doesn’t exist online,” admits Hajer Hmila, a lawyer with expertise in nationality cases, “We [lawyers] just have to learn from experience.”

She recommends that non-citizen adults hire a lawyer because developing relationships with the right administrators can facilitate the process. Additionally, she says, you can’t rely on the information given by various administrations to be consistent: “For every person, it’s never going to be the same experience.”

Aymen, a 44-year-old digital strategist based in the Netherlands, has taken many approaches to sorting out his nationality paperwork over the course of nearly a decade. His saga began when he found a papertrail back to what he calls the “true history of [his] family” after psychologically distancing himself for most of his life from his biological parents: an unknown Egyptian mother and an abusive Tunisian father who disappeared when he was nine years old.

Upon discovering people with his original surname on Facebook, Aymen found that he still has relatives that live in the Bab Jdid neighborhood of Tunis’ Medina. Everyone in his newly discovered family tried to help him claim his Tunisian citizenship. Long-lost uncles and aunts found original documents, nieces and nephews acted as translators, and they even connected him with lawyers who accompanied him to administrative offices and the Ministry of Justice. Despite their best efforts, “there was always something missing,” he recalls, frustrated by the inability to verify information online. After an unending series of setbacks over the course of ten years, Aymen says he became fed up.

“I’m stuck. I don’t know what to do,” he says over a choppy WhatsApp call.

Lingering Article 12 Discrimination

According to the data released to Inkyfada by the Ministry of Justice, 822 adults previously concerned by Article 12 (born abroad to a Tunisian mother and non-Tunisian father) filed nationality declarations between December 1st, 2010 and December 1st, 2011. This narrow one-year deadline set in the 2010 Nationality Code reform was only for these individuals who lost their legal claim to Tunisian citizenship at the age of 18, as articulated by Article 12. Besides the 822, the rest of the individuals in this group still have no claim to citizenship and will have to go through naturalization or marry a Tunisian citizen in order to have citizenship. This bleak reality for a group of unknown size is not widely understood, neither by the people concerned nor by officials with the ability to address this discrimination.

Beyond the straightforward procedure of registering a child as a citizen, “Most lawyers and administrators don't know the full extent of the processes, because it's not codified,” says Abdelfattah Benahji, a senior lawyer with Ferchaoui & Associates and an advisor for several associations working on citizenship-related issues. "Nationality law,” he explains, “is one of the hardest disciplines because of multiple centers of decision-making, a lack of legal deadlines, and rights not being clearly outlined.”

Mounira Ayari, a former lawyer who currently represents Tunisians living in the Americas and various regions of Europe as a member of the Democratic Current party in parliament, says she has "a lot of cases in Europe and all over of individuals who unintentionally missed their chance to apply for citizenship.”

Representative Ayari claims to have “prepared a legislative initiative” that would amend the Nationality Code to reopen and extend the deadline for “the [over-18 children of Tunisian women] who were unaware of the existence of this deadline” and thus “didn’t have the chance to get the nationality.” Though the coronavirus outbreak has postponed her efforts, she claims she is committed to “resubmit[ting] this demand” and hopes “to have a solution in 2020-2021.”

Beyond this specific demographic, it seems that Ayari is confused about the different paths to citizenship that apply to the children of her constituents. She claims that every Tunisian descendent that isn’t registered by the age of 18 has to be naturalized to become a citizen. “Once you’ve passed 18, it is not possible to have the nationality [unless] you justify a continued residency in the country,” she says adamantly. Ayari was informed of the circumstances of my own case as well as the information provided to me by the Nationality Office which disprove her claim, but she still held her position.

The Ministry of Justice, while claiming that not a single nationality declaration was rejected between 1963 and 2010, reports that 489 were unable to be registered. The Ministry does not explain the reasons that prevented these files from being processed. However, it claims that following the 2010 reform, all of these declarations were essentially "dealt with,” without specifying what this means.

WHERE ARE YOU, A "TUNISIAN BY ORIGIN," ON THE PATH TO CITIZENSHIP?

For Tunisians “of Origin” who are over 18, as well as for the individuals covered by Article 12 who missed the one-year statute of limitations to apply for citizenship, there is little to no information on how to proceed. Based on the Nationality Code, firsthand accounts, and the advice of several lawyers, Inkyfada has mapped out the general path to citizenship for non-citizen Tunisians with a claim to nationality.

Naturalizations: “You can wait decades”

“There are no legal deadlines for the naturalization process; you can wait decades,” Benahji explains, in part because, “there are no laws that tie the hands of the Presidency.”

Demands for naturalizations are received by the Ministry of Justice, sent to the Ministry of Interior for investigation, and then forwarded to the Presidency, which has the final word.

If the office of the Presidency decides to grant citizenship through naturalization, the office issues presidential decrees that appear in the official journal of the Republic (JORT) and list the individuals granted citizenship as well as their birth year and place. Some years there are many individuals granted citizenship, other years there are none. This infographic shows the sporadic nature of naturalizations, classified by year, gender, age, and country of birth.

Overlooked Origins

Although knowingly falling outside the State’s current definitions of a Tunisian citizen, many individuals with a personal link to Tunisia have still decided to retrace their family histories, build bridges back to the country, and, in some cases, pursue citizenship.

Camille, a 26-year-old activist, filmmaker, and art space manager, is one of them. She came to Tunisia with a one-way ticket and temporary housing options thanks to an Instagram post from her friend, a Palestinian “influencer,” who reached out to his Tunisian followers on her behalf.

Camille’s mother - the first of her siblings to be born outside of Tunisia - never claimed the nationality through Camille’s grandmother, a Tunisian Jew from the town of Gafsa, who left for France in 1957, right after Tunisian independence. Still, Camille recounts many examples of how the traces of families like hers remain embedded in the nation’s collective memory. One example is a comment that she receives rather frequently: “Ah, you’re a Tunisian Jew, you’re welcome in Tunisia!”

“What do you mean we’re welcome?” Camille wonders sarcastically; “We have been here for three thousand years.”

“So it’s kind of like a middle finger to history,” Camille explains of her desire to get the Tunisian nationality. "Everyone has told me it’ll be impossible to get it,” she says of the citizenship, but she thinks it might “help bring answers to her mother.” She also considers attempting to get citizenship a political act - “to counteract the uprooting committed by colonization, zionism, and Arab nationalism.”

But the paperwork isn’t just a question of identity for Camille; she wants to be able to live normally in Tunisia, with legal residency and work status, health insurance, etc. “I like my life here,” she says, taking a whiff of the sunny air, “there’s not always a need for a moral goal.”

In theory, with the 2010 reform, the equation to reaching citizenship was rendered more simple. The child of a Tunisian parent who emigrated for one reason or another could universally enjoy the same right to citizenship as the child of a Tunisian parent born within Tunisia. But behind the notion of “of course you’re Tunisian” lies a convoluted, uncodified system that demands an extensive amount of time, resources, and persistence to reach an inalienable right. And for the individuals who still don't have the right to citizenship as a result of Article 12, the Tunisian parliament has yet to provide a solution.