The Decree "aims to establish provisions for the prevention and repression of offenses relating to information and communication systems".

The report "Tunisia: Silencing Free Voices - A briefing paper on the enforcement of Decree 54 on "Cybercrime" published recently by the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), states however that "under the guise of combating ‘cybercrime’ and 'fake news', the Decree allows the Tunisian authorities to impose illegal and arbitrary restrictions on the legitimate exercise of the right to freedom of expression".

The witch-hunt against "fake news"

Mahdi Jlassi, President of the National Union of Tunisian Journalists (SNJT), stated that “this Decree is a clear and deliberate political maneuver to suppress press freedom, restrict media operations, and hinder the defense of rights and freedoms.”

Once published, the accusations were soon in full swing. Barely a month after the issuance of the Decree, the Ministry of Transport lodged a complaint against Wajih Zidi, Secretary-General of the General Transport Federation affiliated to the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT).

On October 12, 2022, the Ministry of Transport accused the trade unionist of “disseminating ‘fake news’ with the intent of violating the rights of others”. The complaint referred, among other things, to comments made by Zidi on Diwan FM in January 2023, where he “criticized the declining state of the Tunis Transport Company's equipment and the performance of the Ministry of Transport”.

"How can an opinion be called false information? It doesn't make sense, they're two completely different things," insists Jlassi.

According to ICJ, the Decree "enables the authorities to exert an unwarranted control over what people say, including politicians, journalists and human rights defenders - through the use of surveillance and criminal sanctions, in violation of Tunisia’s legal obligations under international human rights law and standards."

Ines Jaibi, a lawyer specializing in cybercrime and founder of Lab Politik 117, stressed that "it's a tool that can be used against anyone, even though its target is very clear".

Article 24 of the Decree is particularly controversial. The ICJ report warns that "the provisions of the article [...] constitute a serious threat to the exercise of the right to freedom of expression [...] because they are overbroad and vague as they do not define 'fake news' and 'rumors'." The survey conducted by inkyfada, based on ICJ research, revealed that most legal proceedings are in fact initiated under the umbrella of article 24.

Article 24 sentences to

five years' imprisonment and

a fine of fifty thousand dinars anyone who intentionally uses

communication systems to spread

"fake news",

misleading information or

"rumors" with the aim of infringing the rights of others, threatening public security or "sowing terror among the population".

The

same penalties are applicable to anyone using

information systems to distribute

"false information" or

"forged documents" with a view to

defaming others,

damaging their reputation,

harming them

financially or

morally, inciting assaults or hate speech. The

penalties are doubled if the

offender is a

public official or equivalent.

When it comes to legislation, Tunisia's media sector has already been codified. As Mahdi Jlassi asserted: "Following the revolution, laws such as Decree-Laws 115 and 116 of 2011 were promulgated to regulate the field."

In addition, article 37 of the Tunisian Constitution protects freedom of expression. article 38 guarantees the right to information and the right of access to information.

The trade unionist confirmed that there are currently at least " twenty lawsuits pending against journalists on the basis of Decree 54". So far, no information on the exact number of lawsuits based on this Decree has been made public.

"No one is safe"

Inkyfada reported twenty or so cases, representing a wide range of professions: journalists, lawyers, professors, politicians, trade unionists, students active in civil society, to name a few. For Mahdi Jlassi, "no one is safe".

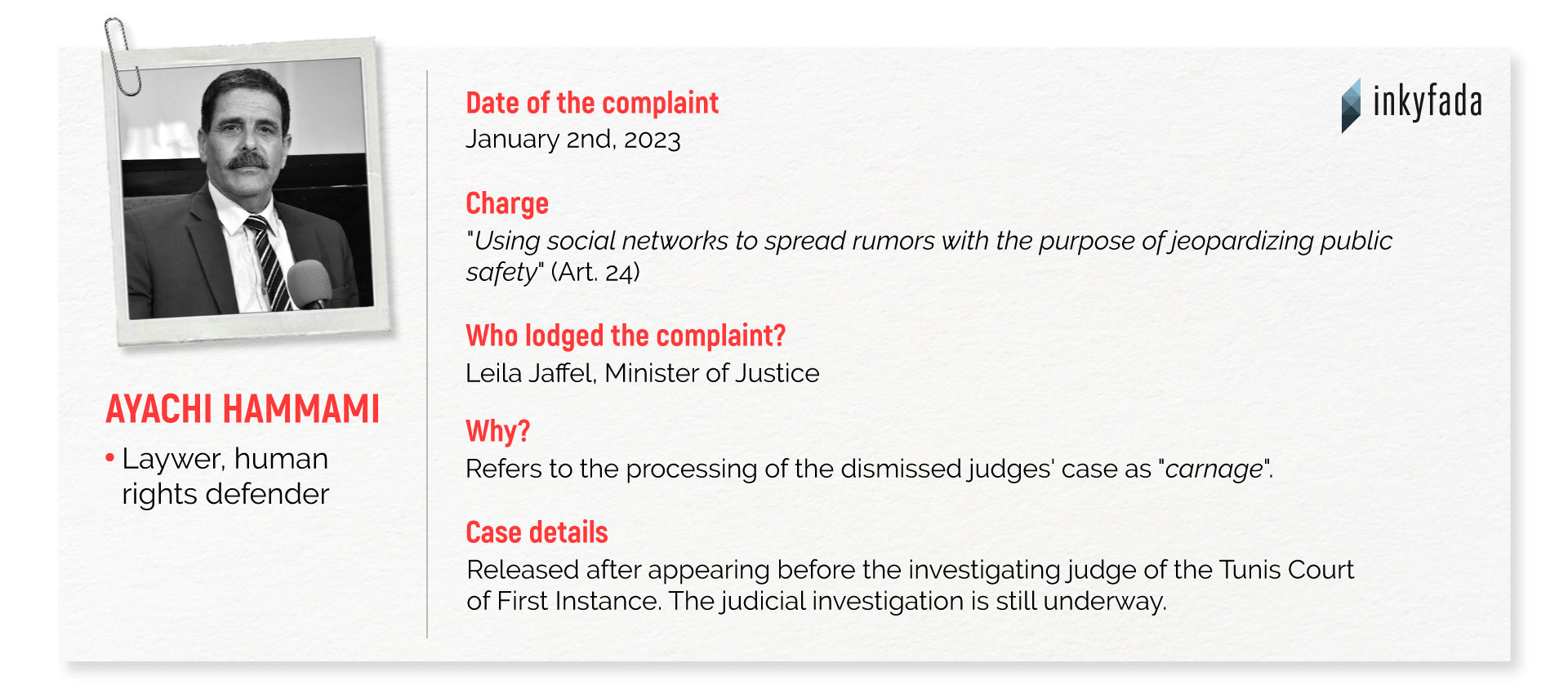

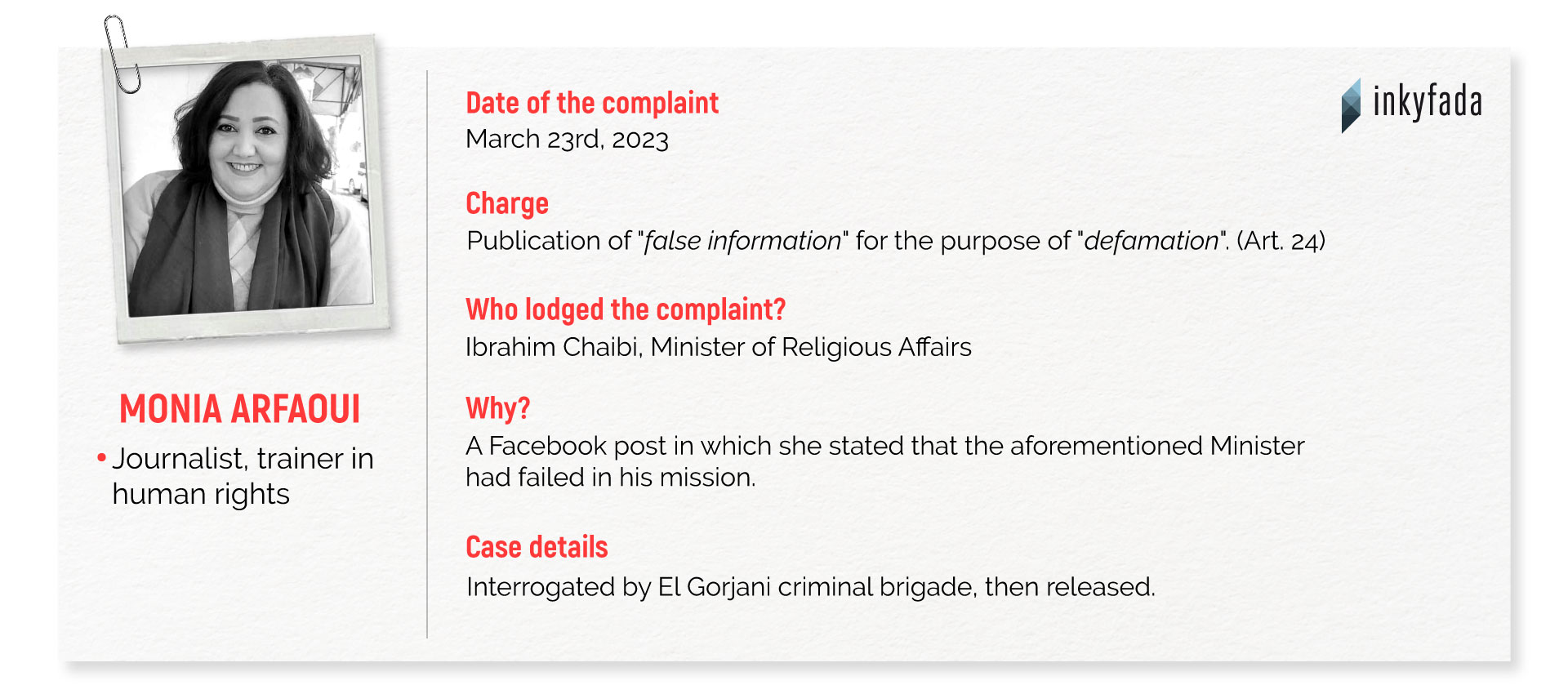

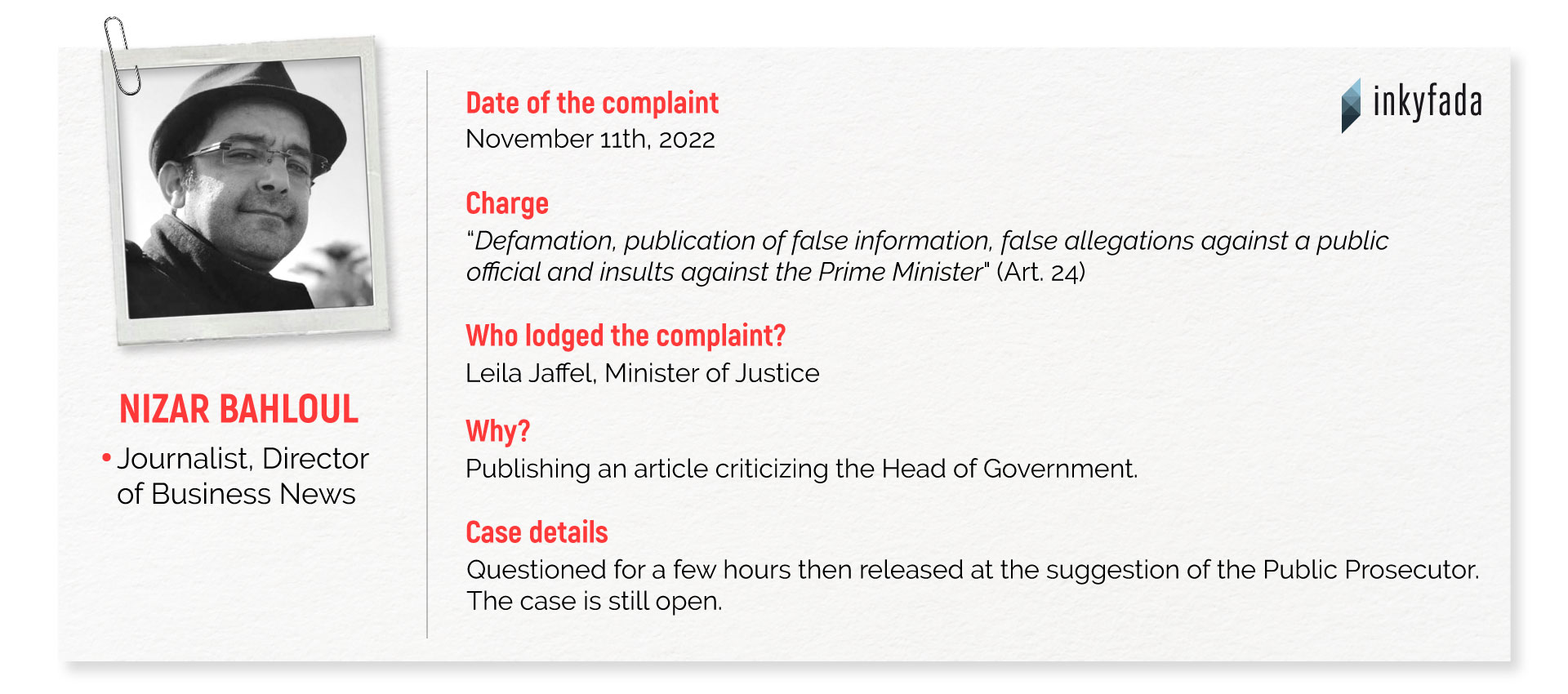

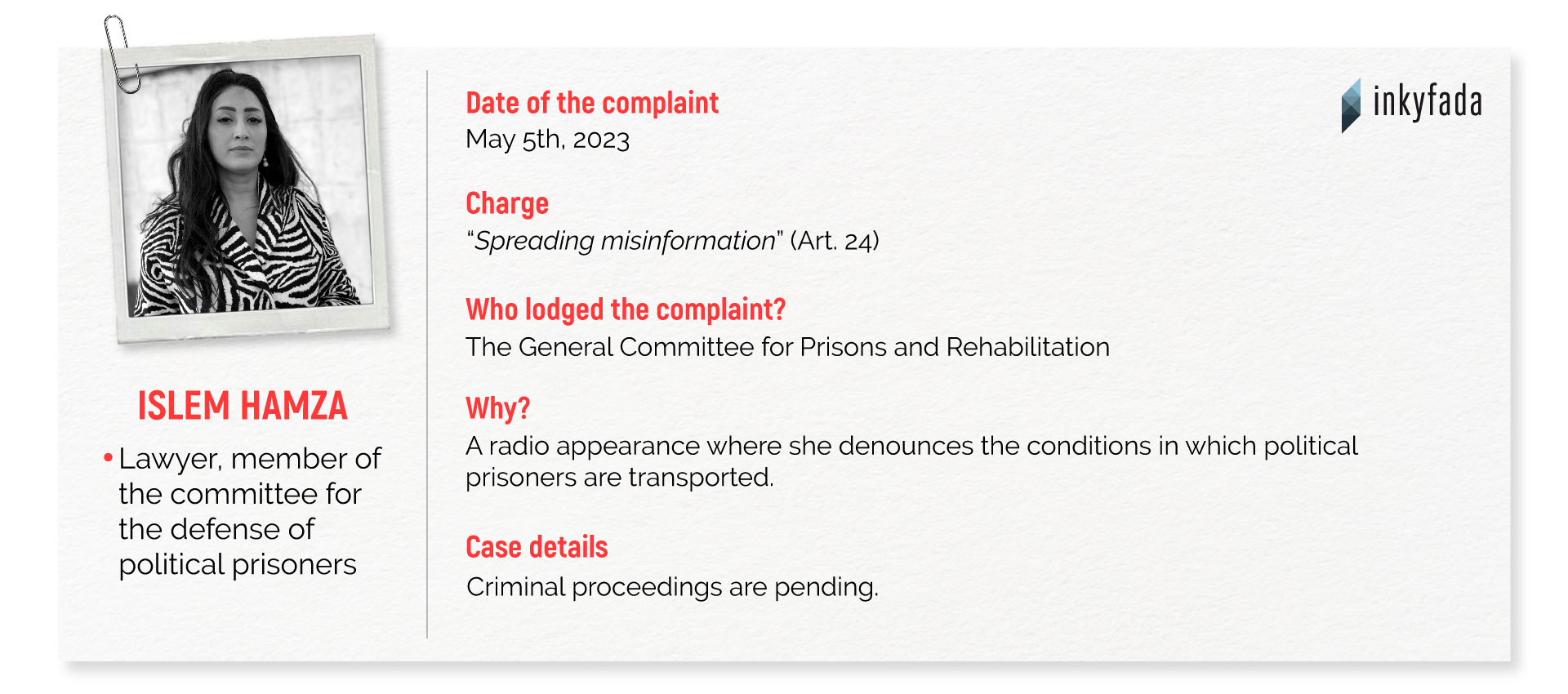

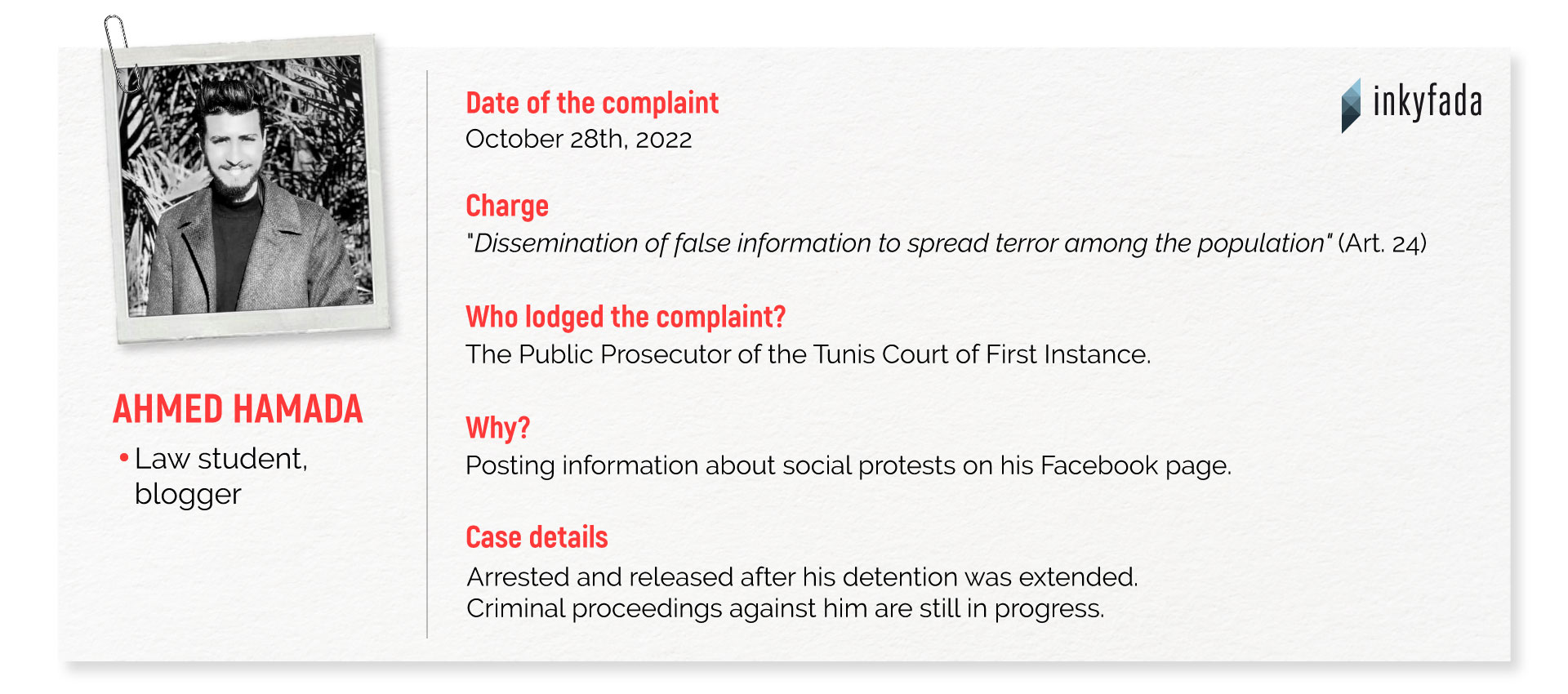

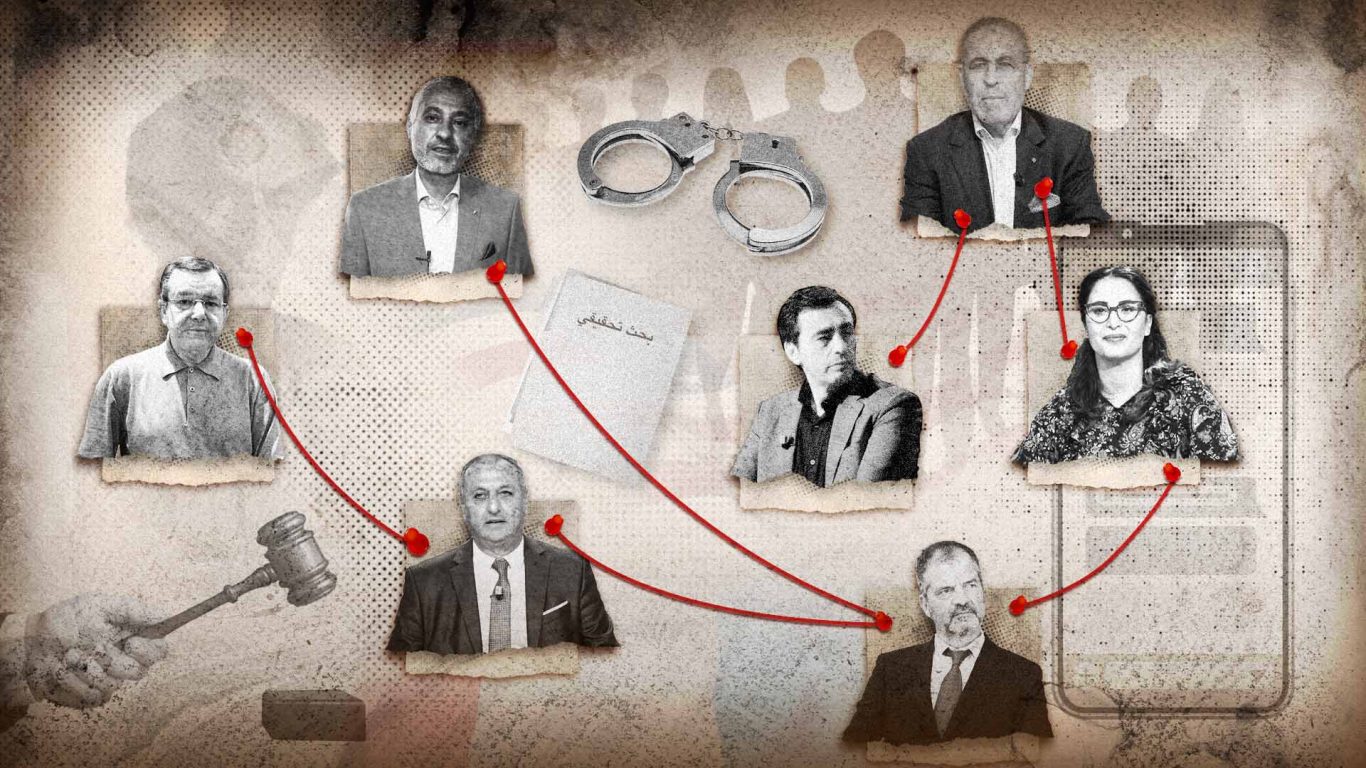

Nizar Bahloul, Ayachi Hammami, Monia Arfaoui, Ahmed Hamada, Mohamed Boughaleb, Islem Hamza, Jaouher Ben Mbarek, Ghazi Chaouachi... The cases against these prominent figures in the media, judiciary, politics, and civil society have received extensive media coverage and close attention. It's important to note, however, that there are several other citizens who are also affected by this situation.

The following infographics illustrate five of the people facing charges under Decree 54, along with the grounds for complaint and the plaintiffs.

[Click on the arrow at the bottom right or left to switch between profiles].

Zied El Heni was the most recent journalist to be prosecuted under Decree 54. During a morning show on IFM on June 20, 2023, the journalist made a joke about article 67 of the Criminal Code, relating to the crime of offending the Head of State.

"This article isn't intended to be used against what is written or said in the press. To offend the Head of State is equivalent to throwing a tomato or an egg at him, or making an obscene gesture as he walks past!"

That very evening, he was arrested and questioned by the Fifth Information and Communication Technology Crime Brigade in El Aouina. When asked if he was referring to the Head of State, he said no, adding that he was " simply explaining the law ".

Zied El Heni was held in custody for over 24 hours. On June 22, he was brought before the Deputy Public Prosecutor of the Tunis Court of First Instance, who ordered his release. He has been awaiting trial ever since.

As far as politicians are concerned, Ghazi Chaouachi and Chaima Issa, members of the National Salvation Front (FSN), have both been sued under article 24 of the Decree for comments they made on Facebook and on the radio respectively.

The activist criticized "the constitutional and political stalemate facing the country since the coup of July 25, 2021", and voiced "doubts as to whether the country's defense institutions [editor's note: the army] would continue to support such a process".

As for Ghazi Chaouachi, he was the subject of a complaint lodged by the Minister of Justice. The lawyer was charged with "spreading fake news with the aim of threatening public security through audiovisual media" and "attributing false information to a public official".

These accusations were made following interviews he gave to a radio and TV station in November 2022, in which he claimed that the Ministry of Justice was fabricating cases against opposition figures and dismissed judges.

The former Secretary-General of the Attayar party appeared before Investigating Judge no. 18 of the Tunis Court of First Instance on June 30, 2023. He was acquitted more than six months after the complaint had been lodged against him, but that didn't mean he was free just yet, as the two activists had been taken into custody in connection with another charge: "plotting against State security".

Chaima Issa was heard by a military court in January 2023. Detained since February 25, she was finally released on the evening of July 13, at the request of her defense team.

On the same subject

The civil society, another target of Decree 54, was not spared either. Activists Hamza Abidi and Mohamed Zantour have been charged with "inciting demonstrations" and "[spreading] fake news with a view to defaming the Head of State", respectively. The charges against the young men are mainly based on Facebook posts.

While the charges against Hamza Abidi were dropped on the day of his hearing by the Public Prosecutor's Office, Zantour appeared before the Indictment Chamber of the Sousse Court of First Instance on June 6, represented by his lawyer. During the hearing, the court decided to extend his pre-trial detention, pending further investigation, as reported in ICJ's research.

A Decree at odds with international law

Since its publication, several international organizations have been thoroughly examining and criticizing the content of the Decree-Law. Through a comparative analysis with international conventions and treaties that Tunisia has signed, these organizations unanimously concluded that the Decree is in direct contradiction with a number of international agreements.

ICJ reiterates that the Decree was issued without "consultation or public debate" and expresses its "deep concern at the alarming prosecutions that have been initiated under Decree 54 and condemns the use of criminal proceedings [...] for the legitimate exercise of their right to freedom of expression, including in the context of the recent crackdown on political dissent in Tunisia."

In an Article 19 report, the organization highlighted that while some of the Decree's provisions were inspired by the Convention on Cybercrime, "most of them do not adhere to international human rights standards, lack adequate due process safeguards, and do not uphold the principles of necessity and proportionality."

The principle of proportionality calls into question the severity of the penalties provided for in the Decree. According to ICJ, "the sanctioning of certain offenses must be proportionate to the severity of the offense itself, a principle which applies to all offenses, including those arising from the exercise of fundamental freedoms, such as the right to freedom of expression."

The organization also referred to the United Nations Human Rights Committee, which stated in its General Comment No. 34 that with regard to defamation, "the application of criminal law should be authorized only be countenanced in the most serious of cases and imprisonment is never an appropriate penalty."

Lawyer Ines Jaibi also denounced the "means of proof" introduced by the Decree.

"Traditional procedures relating to exhibits are not easily applicable in the context of the Decree. It's not easy for a bailiff to authenticate digital evidence. How do we proceed when we have screenshots or when people delete their posts?"

Lastly, the means of surveillance specified in the decree are heavily criticized. Article 10 grants prosecutors, investigating judges, and judicial police officers the authority to intercept communications and access suspects' data, subject to a written and reasoned decision.

According to the ICJ, these provisions are excessively broad and lack clarity regarding the circumstances and individuals affected, which poses a risk to the right to privacy protected under Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

"They listen to the radio, they scroll through Facebook pages, read comments... This type of surveillance is life threatening," warns Mahdi Jlassi.

Additionally, Article 9 can be used to access data held by journalists without adequate protection, risking the confidentiality of journalistic sources, which is a crucial aspect of the right to freedom of expression protected under Decree-Law no. 2011-115 on freedom of the press.

Article 9 is all the more concerning considering that a legal precedent sparked outrage a few months ago. Journalist Khalifa Guesmi initially received a one-year prison sentence for refusing to disclose his sources, but the Court of Appeal extended his sentence to five years. Guesmi was charged with "disclosure of information".

Both Mahdi Jlassi and Ines Jaibi mentioned the emergence of a "climate of self-censorship" due to these provisions. The lawyer admitted, "Even when joking, people feel it's safer to remain silent rather than risk being targeted by the Decree."

Given this climate of intimidation, Jaibi expressed the hope that "the Decree will be rescinded so that we can start afresh".

Based on the same reasoning, the ICJ presented crucial recommendations in its report. These include the immediate repeal of the Decree-Law, dropping charges against those prosecuted under it, and providing compensation for the damage caused by these arbitrary prosecutions.