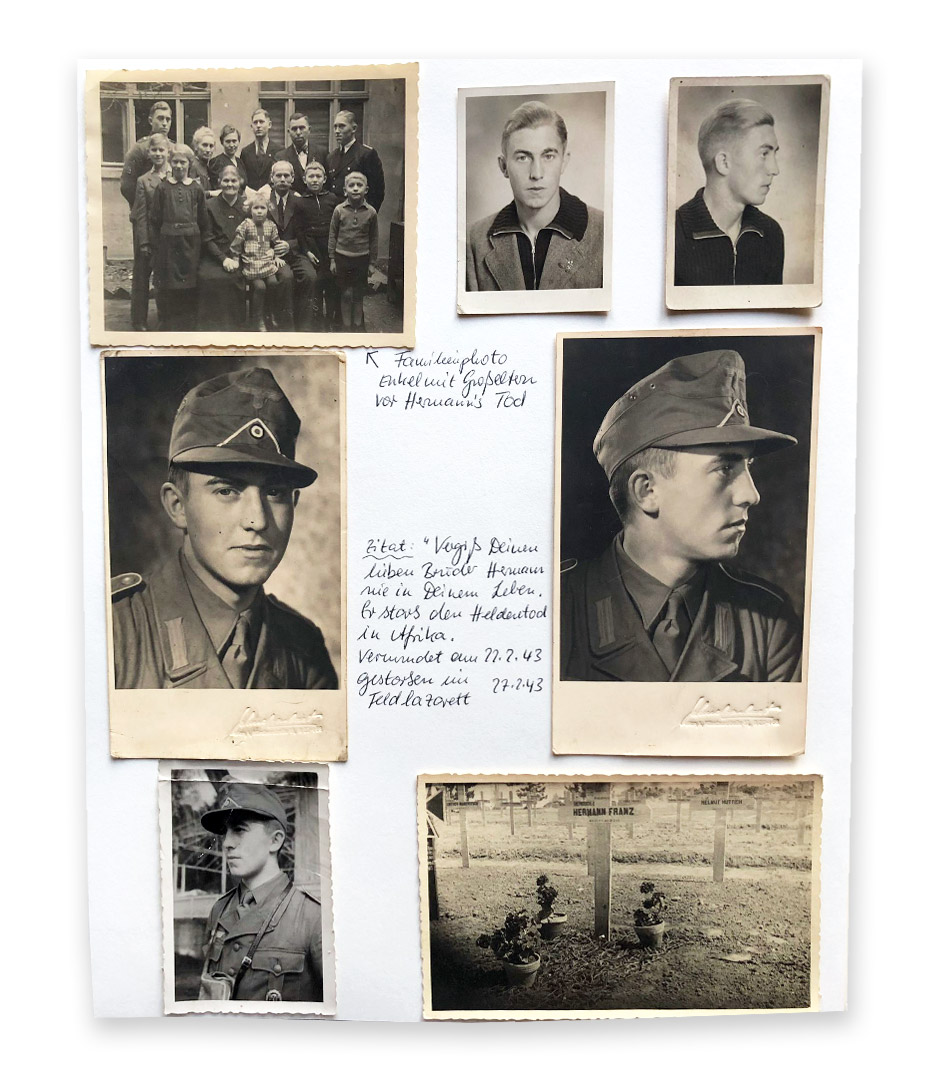

“Never forget your dear brother Hermann in your life. He died a heroic death in Africa. Injured on 22.2.43, died in the field hospital 27.2.43.”

Underneath the text, there is a photo of Hermann’s grave. A plain wooden cross with his name, birth date and date of death, surrounded by three flower pots that stand on the dusty soil. The photo of his grave was taken in Sfax, where Hermann was first buried after he died from his wounds that he obtained from a shrapnel during fighting near Kasserine.

The page with Hermann’s photo in my aunt’s photo album. In the top left corner one can see a family photo of Hermann, his siblings, parents and grandparents. On the photo, one can see Hermann on the top left.

Hermann Franz was my great-uncle. He was one of the 170.000 German soldiers who fought in Tunisia during the Second World War and among the over 8500 of them who died in Tunisia during that same war. Sitting there, in my aunt’s living room, looking at Hermann’s photos, I was asking myself: What were German soldiers like my great-uncle doing in Tunisia during the Second World War? And how did this affect the lives of Tunisians at that time?

How the Second World War was brought to North Africa

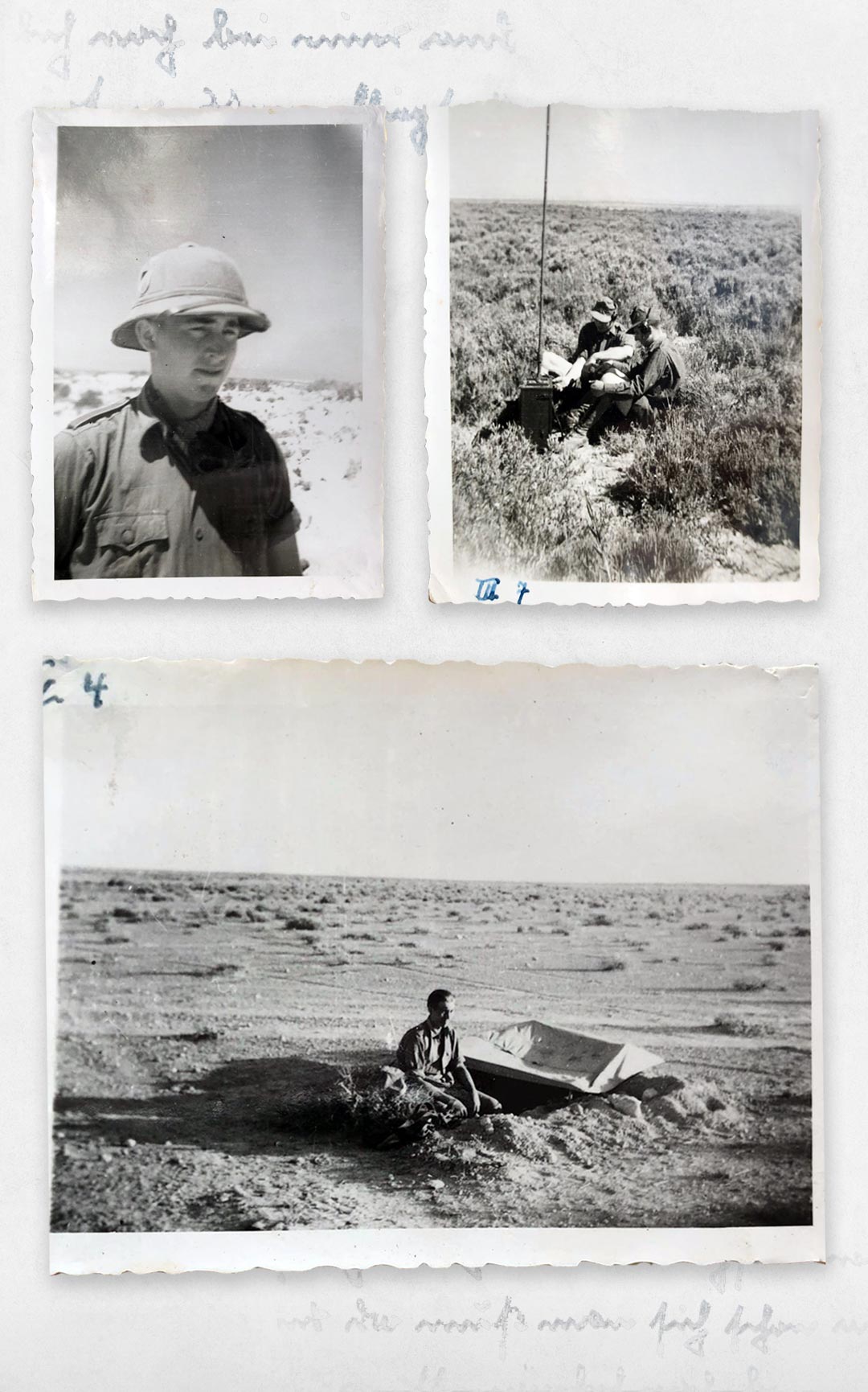

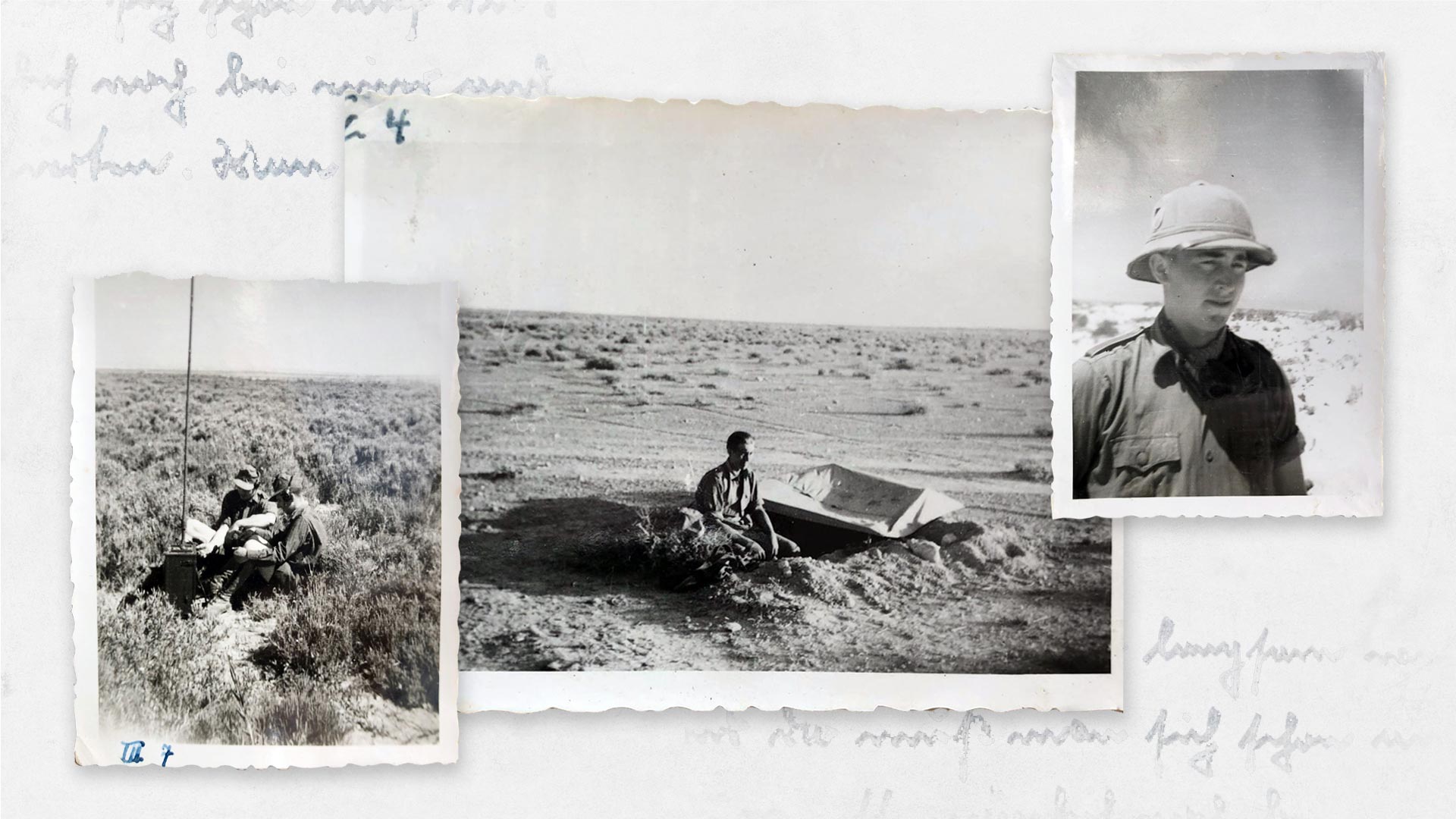

“My dears! Warm greetings from Africa. We arrived here safely. We all expected it to be very hot here, but we have been disappointed because you can still wear a coat even. At the moment, we are here waiting to be picked up. To our left, there is the water and to the right there are stones and sand.” - Hermann Franz in a letter to his family in the beginning of May 1942. At that time, he and his unit had just arrived in Libya.

The reason why German soldiers were sent to North Africa in the first place, was to support Germany’s ally Italy. Italy had entered the war on the side of Germany in July of 1940 by declaring war on Great Britain and France. Already before that, Benito Mussolini, the fascist dictator at that time, had declared his goal to establish Italy as a major power in the international power structure. This included the expansion of its colonies to countries such as Egypt and Tunisia.

To achieve this goal, in September of 1940, Italy started a large-scale offensive against the British Commonwealth troops that were stationed in the sovereign Kingdom of Egypt, where Mussolini and his army were quickly defeated. In order to prevent the collapse of its ally Italy, Adolf Hitler thus felt compelled to send German troops to Tripolis in February of 1941. What followed after that were two years of fighting which my great-uncle Hermann joined in May of 1942. Half a year later, in November, the “Axis”, which consisted of German and Italian troops, were then heavily defeated by Great Britain in the battle of El Alamein in Egypt.

After that, for a short time, Hermann had the hope to return home to his family. On 22nd of November 1942, Hermann wrote to his family:

“The best thing of all is that we were supposed to be pulled out of Africa in the coming days. I didn't write anything because I wanted to surprise you. Now it probably won't happen. We had everything packed perfectly, including great food, which is now all burnt. I only have blankets, a coat, and what I'm wearing”.

Peter Lieb, a German military historian from Potsdam, tells me that while there were plans temporarily to withdraw completely from North Africa, Hermann most likely was unaware of this. “I firmly believe that your great-uncle did not know about this. But in every army rumors circulate constantly and everywhere. Armies are the biggest rumor mills in the world”, he says.

Tunisia turning into a battlefield

Around the same time of the defeat in El Alamein, the Allies launched “Operation Torch” with 107.000 British and American soldiers landing in Morocco and Algeria who then quickly made their way towards Tunisia. For the Allies, a victory in North Africa would have been an important step to later defeat the German Reich. For Hitler and Mussolini, however, “Operation Torch” was a strategic catastrophe, as it threatened the entire western Mediterranean from the south.

“If the Allies would have taken North Africa, they would have landed in Southern Italy soon after, which would have threatened the Italian homeland”, says Peter Lieb. As a result, the Axis' goal was to keep the British and American soldiers as far away from Tunis as possible.

In order to achieve that, starting from November 1942, “the Germans and Italians sent incredible amounts of material and personnel to Tunis”, says Peter Lieb. In total 137.000 German soldiers, 40.000 Italian soldiers, 495 tanks and around 975 artillery pieces were flown into Tunisia between November 1942 and April 1943.

German paratroopers in Tunis in November 1942 - Wikimedia Commons

At the same time, in November 1942, the armored army led by field marshal Erwin Rommel withdrew further and further westward through Libya, reaching the Tunisian border around mid to late January of 1943. This means that while reinforcements were sent to the North of Tunisia from Germany and Italy, Rommel and his army were coming from the South. My great-uncle Hermann was part of this army and wrote to his family on 29th of January 1943:

"We are (...) already in Tunisia. Libya belongs to the Tommy* now. I'm sure you all made stupid faces when you heard that Tripoli was evacuated. We have been expecting it for a long time already. The area from Alicurata to Tripoli is particularly wonderful. We felt really comfortable there. But here in Tunisia, we can't complain either. It is getting better by the day. You cannot imagine how wonderful it is to come back to an area where there are proper cities and where the ground is covered in vegetation after having lived in this desert of sand for so long."

From 17th November 1942 until 13th of May 1943, Tunisia then turned into an important battlefield of the Second World War. Germany and Italy were fighting on one side against Great Britain, its Commonwealth troops, the USA and the Free French on the other side. And with them, not only two coalitions, but also two opposing worldviews were battling with each other in Tunisia: National Socialism and Fascism versus Democracy.

A new occupying power

When the allied and axis powers arrived in Tunisia in November 1942, the country was under French colonial rule. However, at that time, Italy also claimed ownership of Tunisia, which the Germans wanted to prevent out of fear that the Italians would not be very popular among the Tunisian population.

Germany, though, was also not interested in directly occupying the country themselves. According to Faysal Cherif, who teaches military history at the University of Manouba and who wrote his thesis about the Second World War, “the priority for the German army was battles, was to win the war. They did not have much time to lead the politics. Everything had to go into fighting”. As a result, instead of directly occupying the country, Germany brought the French colonial administration into their service. “For six months, the Germans organized everything here in Tunisia”, says Faysal Cherif.

The new occupying power was quite popular among the Tunisian population. “There was definitely a considerable amount of people that perhaps didn’t see the Germans as liberators, but as a power that could mean the end of colonial rule. The Germans are the opponents of the British and French, and the enemy of my enemy is my friend, so to speak”, says Peter Lieb.

Hermann also experienced this and wrote in a letter that he sent from Tunisia to his family: "The Arabs are very fond of us, we are received enthusiastically everywhere we go".

The Germans also used their popularity among the local population to indirectly target the British and the French through propaganda. “The propaganda was telling people: ‘We are not going to colonize you. We are only here to win against the French, British and American Forces’”, says Faysal Cherif. According to him, around 5000 men from Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia even joined the fights on the side of Germany, while others fought with the French colonial troops together with the Allies.

Daily life in a war-torn country

"My dear ones! A few days that brought us several hard fights are behind me. Some comrades were killed, unfortunately this is how it had to be. I was lucky again throughout everything, let's hope that the soldier's luck will continue to be with me. (...) Do not worry if there is no mail from me for a long time. Best regards to all of you, your Hermann."

This was Hermann on 21st February 1942 in what would be his last letter. One day later he was fatally wounded.

The fighting between the allied and axis powers all over Tunisia had a drastic impact on not only the soldier’s lives but also the lives of Tunisians at that time. Many people had to leave their homes that were ravaged by bombardments, turning thousands of people into refugees within their own country. At the same time, people’s mobility within Tunisia was heavily limited due to the fighting, with trains having been assigned solely to the transport of troops and much of the infrastructure having been destroyed.

Destroyed buildings in Sousse after they were hit by an air raid in 1943 - Wikimedia Commons

In addition to that, the successive bombardments of towns and villages hampered the transport logistics and work in the field. Battles at sea hindered import ships from reaching Tunisia. As a result, basic goods became scarce, the inflation increased sharply and the black market started flourishing.

While the official price of one kilo of bread at that time was at 4,40 Tunisian francs, the same amount was sold on the black market for 20 to 60 Tunisian francs. The price of sugar increased by nearly 3800% and the price of chicken by more than 500%. At the same time, food rationing became increasingly strict with only 300g of bread per day and 500 ml of oil per month being allocated to each person.

“In front of the stores, where occasionally some products were sold, there were always endless queues, from which the soldiers in uniform were immediately served”, Faysal Cherif describes in his book “Tunisia in the turmoil of the Second World War”. The few remaining supplies were thus often bought up by the foreign occupying powers in the country which further exacerbated the situation for the local population.

The dire situation of the war also led to the outbreak of epidemics such as typhus*, from which an estimated 863 people died between 1942 and 1943. As a comparison, before the war, from 1935 to 1939, only a total of 33 deaths were caused by typhus.

The standard of living in the country deteriorated progressively as fuel was lacking and railways, roads, ports and power stations were bombarded. Schools had to close and unemployment was rising. For many Tunisians, the only option to earn some money and obtain basic supplies was to work for the Germans and Italians, for example, by clearing the streets from rubble and extracting the dead or wounded that were buried under the destroyed buildings.

According to the Hague Convention on War on Land, which outlines rules about conducting war, forced labor is not explicitly prohibited, but it should be compensated. While a part of muslim Tunisians did get paid for their work for the German occupation power, the situation looked different for jewish Tunisians. Starting from 6 December 1942, the compulsory labor service (S.T.O.) was imposed on the Jews of Tunisia, especially those living in Tunis, according to Faysal Cherif.

Jewish forced laborers in Tunis in December 1942 - Wikimedia Commons

Historian Dorsaf Nehdi writes in her dissertation: “Many Jewish youths tried to hide in order to escape forced labor in the German camps. This was not easy, as the eyes of the Nazis were everywhere. Only a few escaped the iron grip of the Nazis.” As a result, thousands of jewish men were forced to work in the German camps in Tunisia and could not leave them during the whole period of the German occupation.

However, many jewish Tunisians also found refuge with muslim Tunisians and were thus able to escape German repression. Besides having to work for the occupation authorities, the jewish community in Tunisia also had to pay collective fines and the Great Synagogue of Tunis was transformed into a warehouse. The Italian-jewish community living in Tunisia at that time was spared from the measures adopted by the German military authorities against Tunisian Jews.

Hermann’s letters from the battlefield

"Dear Mom, warm congratulations on your birthday. I especially wish that you will recover soon and remain with us for a long time. Hopefully, next year we will have the opportunity to celebrate your birthday together in peace. Wishing you all the best once again. Your son, Hermann Franz."

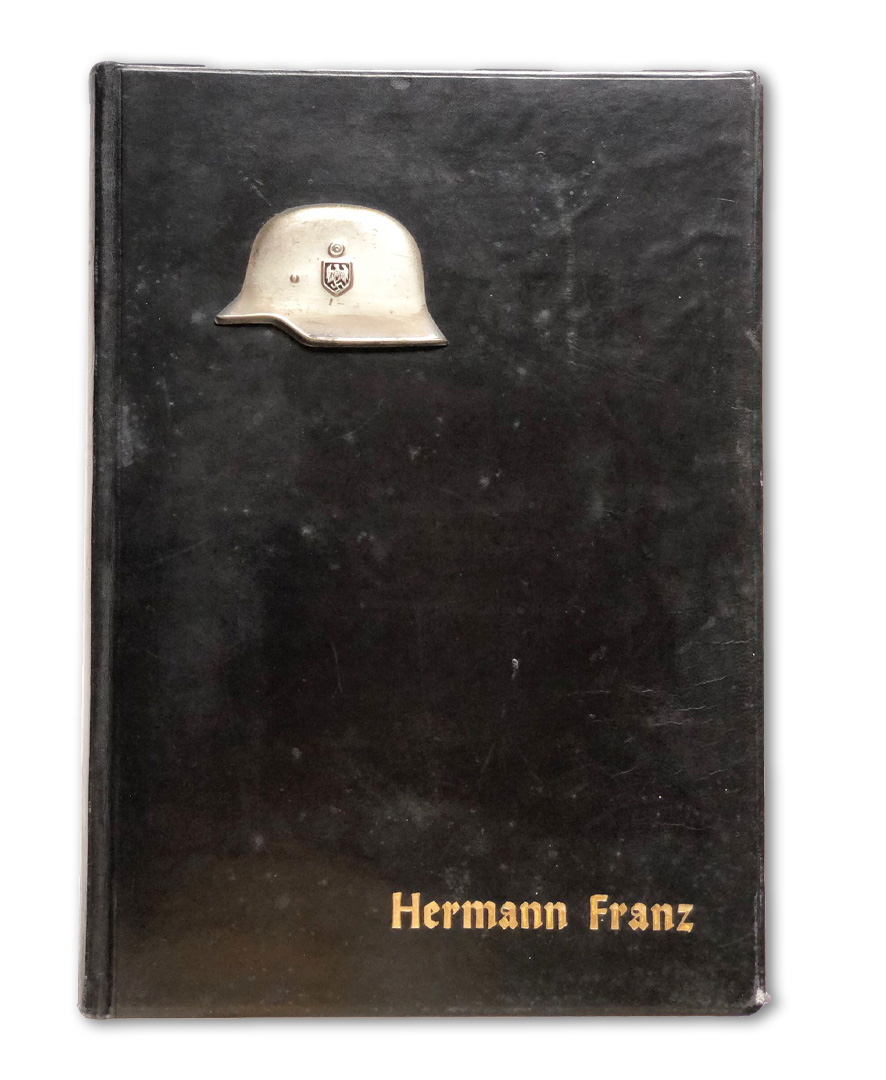

A few months after Hermann's death, his father - who was my great-grandfather - transcribed all of his oldest son’s letters by hand and made a book out of them. He added the photos that Hermann had taken, a list of the battles he had fought in as well as all letters related to his death which the Chief Medical Officer and one of Hermann’s comrades had written to the family.

The book that Hermann’s father made after his death and in which he collected all letters and information about Hermann’s time in North Africa.

The way Hermann writes reminds me of how my younger brother writes. There is a certain lightness in the way he describes the weather and the areas he passes through. He is very thoughtful, congratulating his family members for their birthday’s or his mum and grandmother for mother’s day. In some letters, one can feel how much he misses home and his family, when he talks about how he wishes he could join them for their vacation or birthdays.

I feel sorry for this young man who was only 19 when he became a soldier and for the family that he was taken from. But while reading his letters, I also wonder how honest he was, how honest he could be. And how convinced he was of the oppressive ideology that he was fighting under and which I despise so much.

In his book “War in North Africa”, Peter Lieb writes about the ideology of German soldiers like Hermann at that time: “The Allies found a greater affinity for the Nazi regime among the German prisoners in North Africa than later, in 1944, in Western Europe. Rommel's soldiers were still confident of victory, at least until 1942. For many of them, National Socialism had not yet lost its luster.”

This conviction that the war is not yet lost can be found in Hermann’s letters too, despite the fact that he usually does not write much about his thoughts on the war. As no one who personally knew my great-uncle is alive anymore, I thus simply cannot know how convinced he was of the ideology and the regime that he was fighting for. With the help of Hermanns field postal code that is noted above one of his letters, Peter Lieb tells me that Hermann was most likely part of the “Brandenburg Training Regiment”, a special unit that often fought behind the front. And he also tells me that soldiers in this specific unit were often volunteers.

Photos of Hermann during the war in North Africa

There is a possibility that Hermann volunteered for military service even though we cannot know for sure. In one of his letters, Hermann writes to his younger brother Rudi about his thoughts about the war, sounding disillusioned, as if it’s not how he expected it to be:

“You young folks see the war only in terms of Iron Crosses and other decorations due to your youthful recklessness. All that glitter is not gold, and I've already gotten used to that. You'll also learn your lessons the hard way! Nevertheless, I don't want to come across as a coward, but let me tell you this: Anyone who has experienced the true nature of war knows what's going on. So let me tell you this: Be glad if you can spend some more time at home, you'll have to admit that I'm right sometimes. You know how I used to feel.” - Hermann to his younger brother Rudi on 13th October 1942.

The last offensive

In February of 1943, the Germans and Italians started what would be their last offensive. They planned to break through the front of the American and French troops in order to then advance further towards the northwest of Tunisia and Algeria. The German Africa Corps - and with them my great-uncle Hermann - advanced towards Kasserine where eventually, in mid-February, the battle of Kasserine took place.

During this battle, on 22nd of February, Hermann was injured by a shrapnel that had penetrated through his abdominal wall into the colon. The injury took place on the street between Kasserine and Tebessa, 15 to 20 kilometers from the border to Algeria. Five days later, on the 27th of February, Hermann died in a field hospital from his wounds.

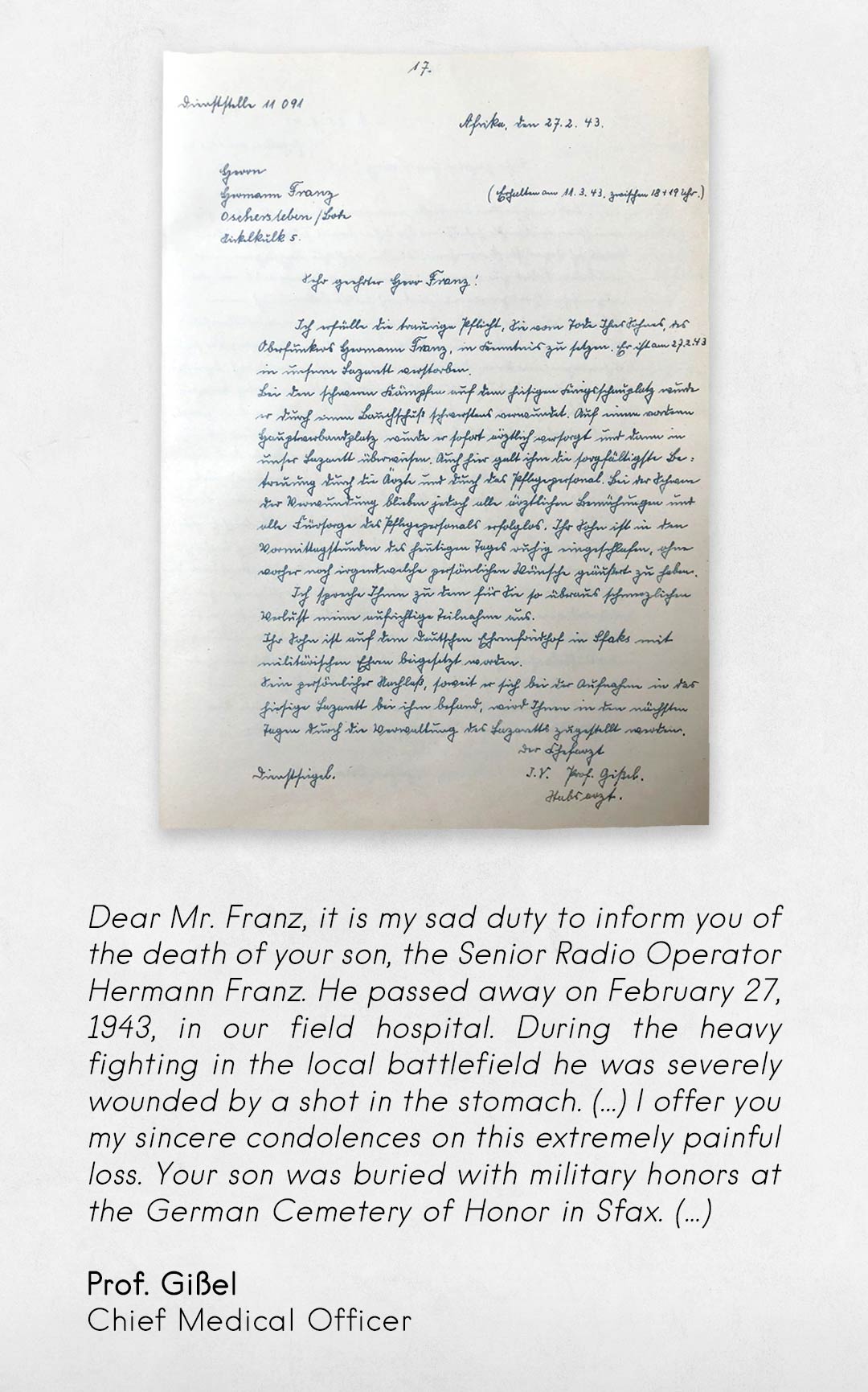

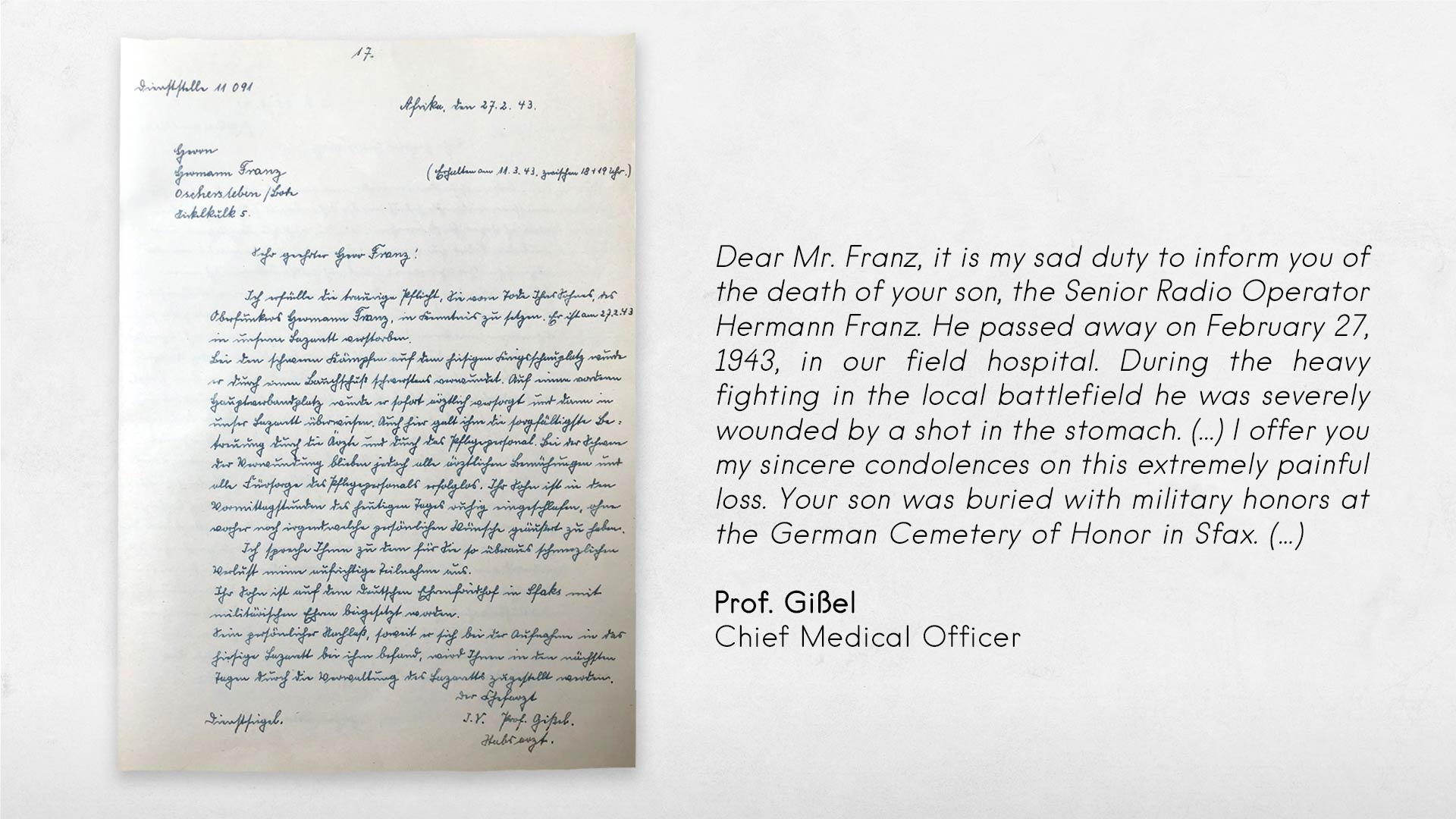

His parents learned about his death on 11th of March 1943. Herrmann's father even noted the time he received the letter: “between 18 + 19 o’clock”.

Letter written by the Chief Medical Officer Prof. Gißel, informing Hermann’s parents about his death.

After Hermann’s death, the Chief Medical Officer and one of Hermann’s comrades exchanged letters with his father in which they explained the circumstances of his death and sent photos of his grave as well as two letters that Hermann had written but not yet sent to his family. According to the Chief Medical Officer, in the field hospital "he [Hermann] himself had no idea about the severity of his condition. (...) He died believing he could go home on the next hospital ship and was looking forward to seeing his parents again”.

The surrender of Germany and Italy in Tunis

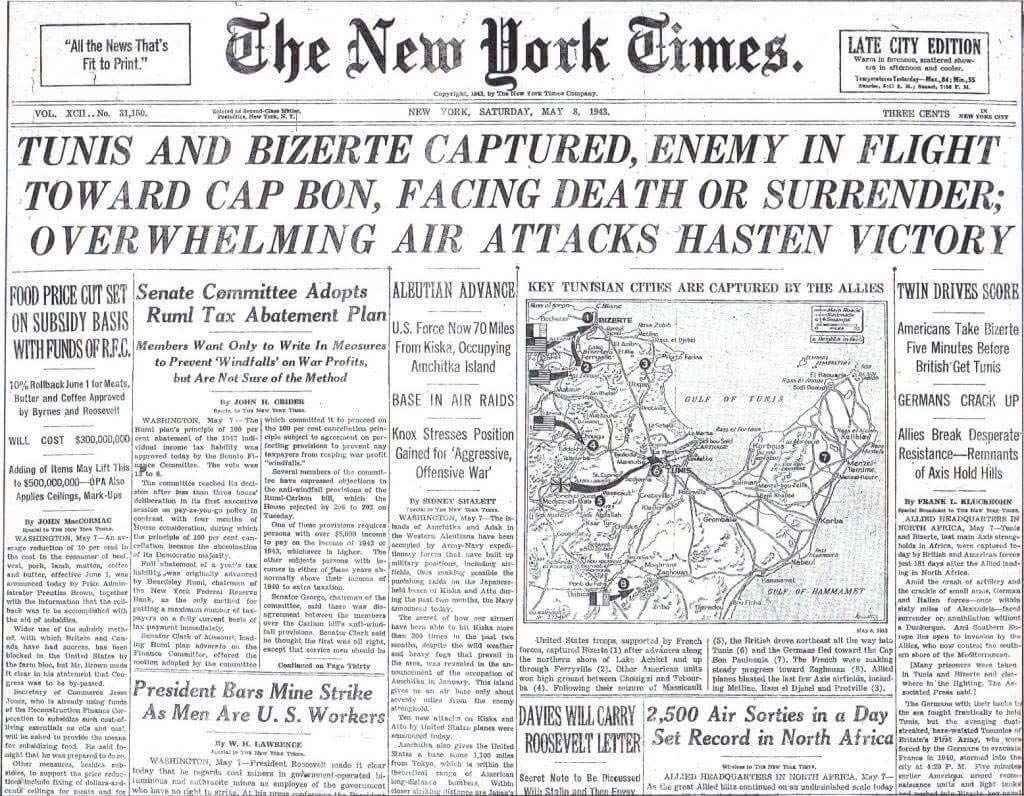

With the failure of their last offensive in Kasserine, it was clear that Germany would not be able to further maintain control of Tunisia. After a few more weeks of procrastinating the fighting, the German and Italian troops finally surrendered in Tunisia on 13th of May 1943.

The cover of the New York Times on 8th of May 1943 - Wikimedia Commons

Allied troops entering Tunis and marching in front of the Cathedral of Saint Vincent de Paul and Saint Olivia of Palermo - Wikimedia Commons

By that time, according to Faysal Cherif, around 90.000 people had lost their lives in Tunisia, most of which were allied or the axis soldiers. However, also 8000 Tunisian civilians were among the dead. Around 250.000 German and Italian soldiers became prisoners of war of the Allies. After the German and Italian surrender, these prisoners of war had to, for example, help build up the infrastructure of Tunisia that was destroyed during the fighting, according to Peter Lieb. To escape the imminent imprisonment, some German and Italian soldiers tried to flee by boat to Europe. Others stayed in Tunisia even after the war. “There were many German soldiers that were hidden by the population. They disguised themselves like Tunisians so they don’t get recognized”, says Faysal Cherif.

German prisoners and their guards wait in a roadside ditch near Kairouan in April of 1943 - Wikimedia Commons

German soldiers being rounded up by the Royal Navy around 30 kilometers in front of Cap Bon after having tried to flee by boat from Tunisia - Wikimedia Commons

According to Peter Lieb, Tunisia was an “extremely important area of conflict” during the Second World War. At the same time as the Tunisian Campaign, the Battle of Stalingrad was taking place, which was the first major defeat of the Germans and one of the turning points of the Second World War. The Tunisian campaign influenced this battle indirectly, says Peter Lieb: “One could go so far as to say that if the Germans had deployed their planes and tanks to Stalingrad instead of sending their troops to Tunisia, the Battle of Stalingrad would likely have looked different”.

For Tunisia, the Tunisian campaign also had a lasting impact. Both Faysal Cherif and Peter Lieb agree that this period of time sped up the Tunisian independence movement. “The Germans and Italians buried many arms after their defeat and didn’t give them to the Allies. Many Tunisians used these arms during the Tunisian revolution in 1952 to 1954. They also learned how to fight a war, the strategy and how to attack”, says Faysal Cherif.

In addition to that, the fact that at least for a short period of time, the German occupation power took over the French colonial rule had an accelerating impact on the Tunisian independent movement. “This is a phenomenon that can be seen globally over and over again, also in other African or East Asian countries, because the population sees that their colonial rulers are not invincible”, says Peter Lieb.

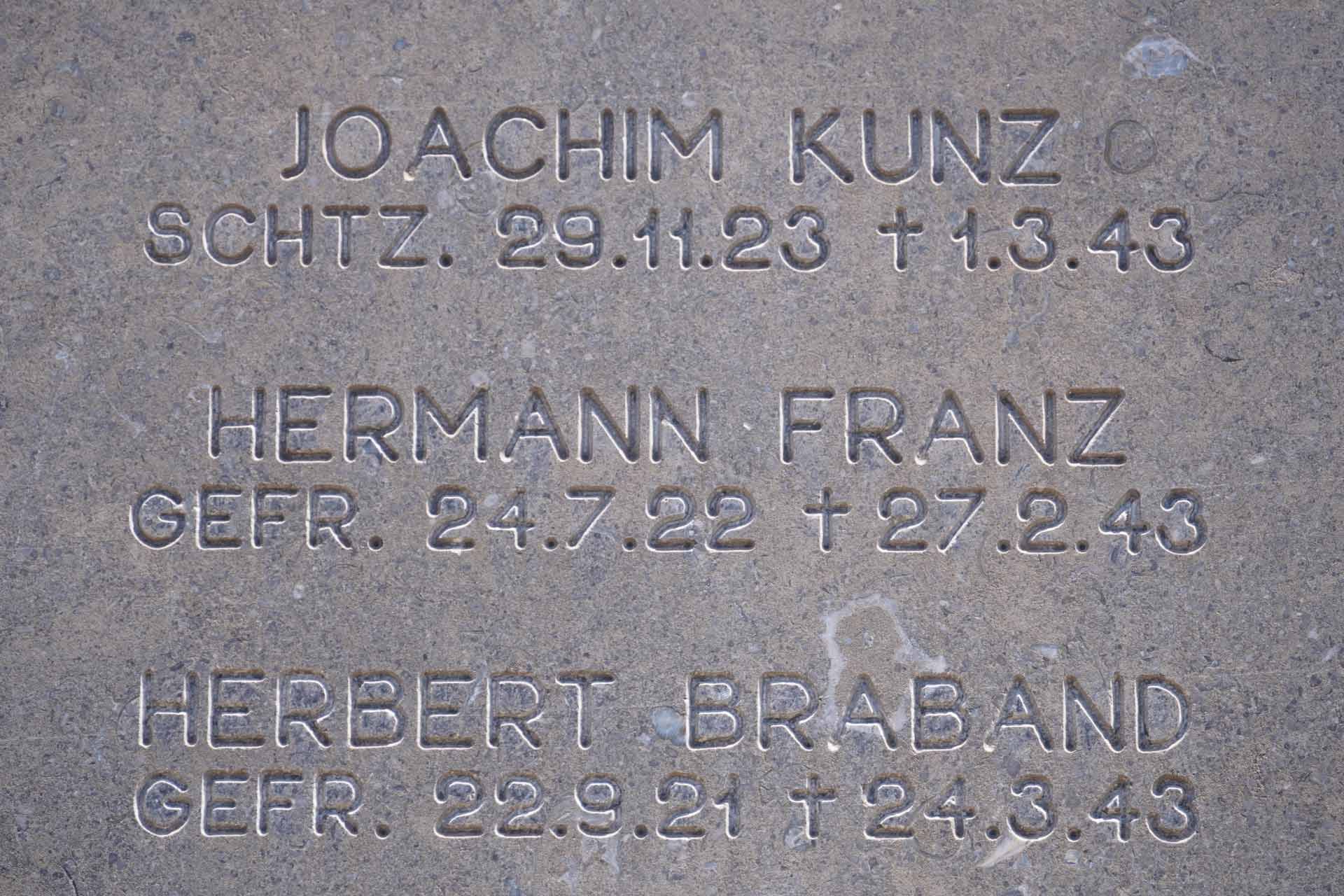

Today, my great-uncle Hermann is buried in the German military cemetery in Borj Cedria together with 8561 other German soldiers that died during the Second World War in Tunisia. They were initially buried in different cemeteries all over the country until in 1966 Tunisia and Germany signed an agreement to establish the military cemetery in Borj Cedria. The recovery of the mortal remains and their transfer was carried out in 1974 by the reburial service of the German War Graves Commission.

German military cemetery in Borj Cedria where Hermann Franz is buried today

After an almost 45-minutes drive from Tunis, we reach the military cemetery in Borj Cedria. It is located on top of a small hill, with a view to the sea and the Mount Boukornine National Park. The complex consists of six individual yards, each of them representing the location of one of the original war cemeteries. We walk past a stone wall with the inscription “Sfax”. Here, on an ossuary with the number six, we find my great-uncle’s name, his birth date and date of death. For the first time, more than 80 years after his death, a family member of Hermann came to visit his grave.

Hermann Franz's grave in the German military cemetery in Borj Cedria, initially buried in Sfax following his death in 1943.