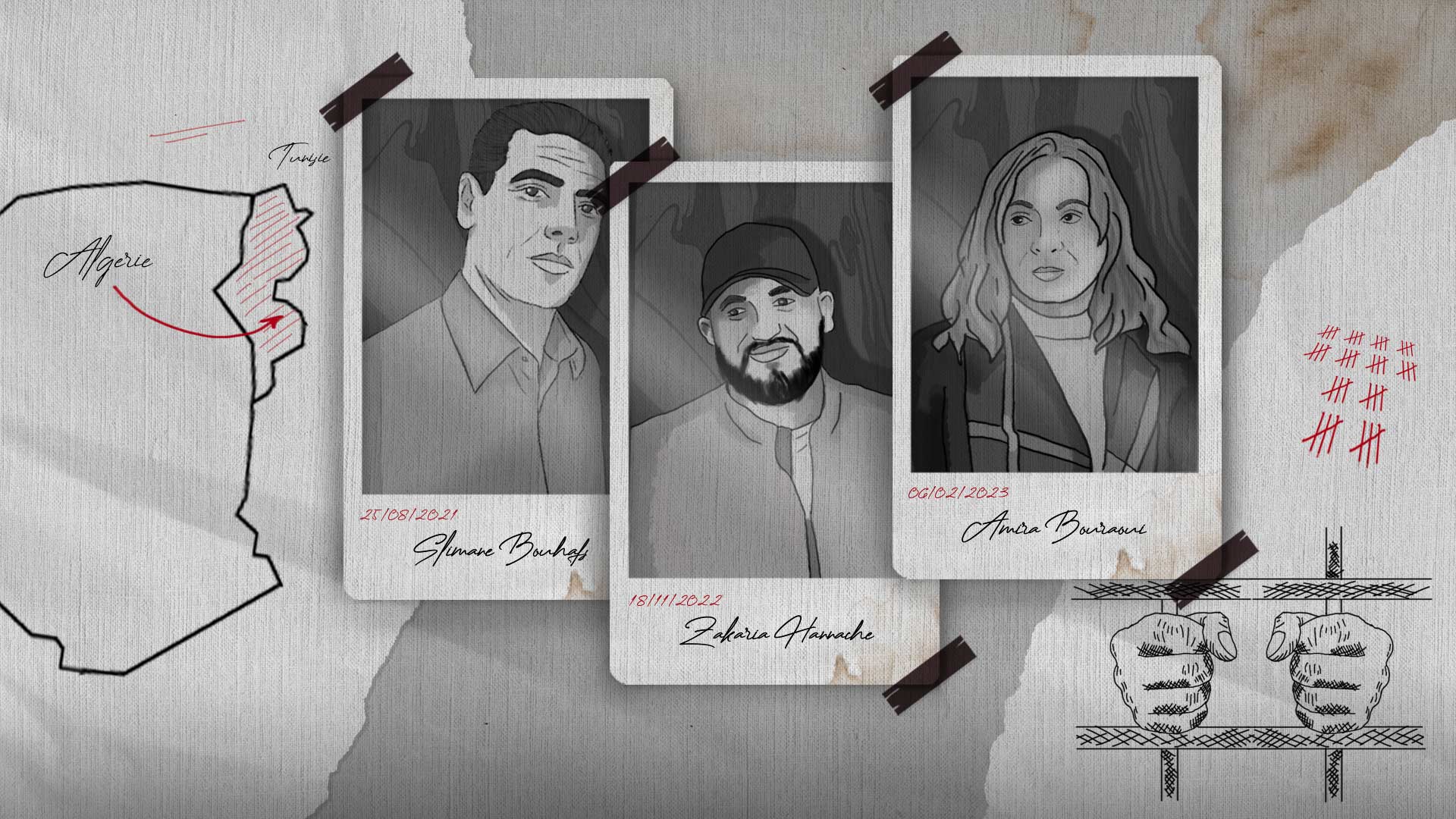

While Tunisia is plunging into a socio-economic crisis, in a climate of increasing political arrests, these three cases reflect the lack of security for Algerian opponents seeking refuge.

"The consequences of the current situation in Tunisia will have a decisive impact on the safety of Algerian activists who have taken refuge in this country," stressed an anonymous source close to the case. "It's important to act as quickly as possible," confirmed another source who wished to remain anonymous.

Algerian opposition figures

In 2019 and 2020, protests have shaken Algeria. The Hirak criticized President Abdelaziz Bouteflika's successive terms in office and the election of his successor Abdelmadjid Tebboune. This movement saw the emergence of several personalities who became symbols of opposition.

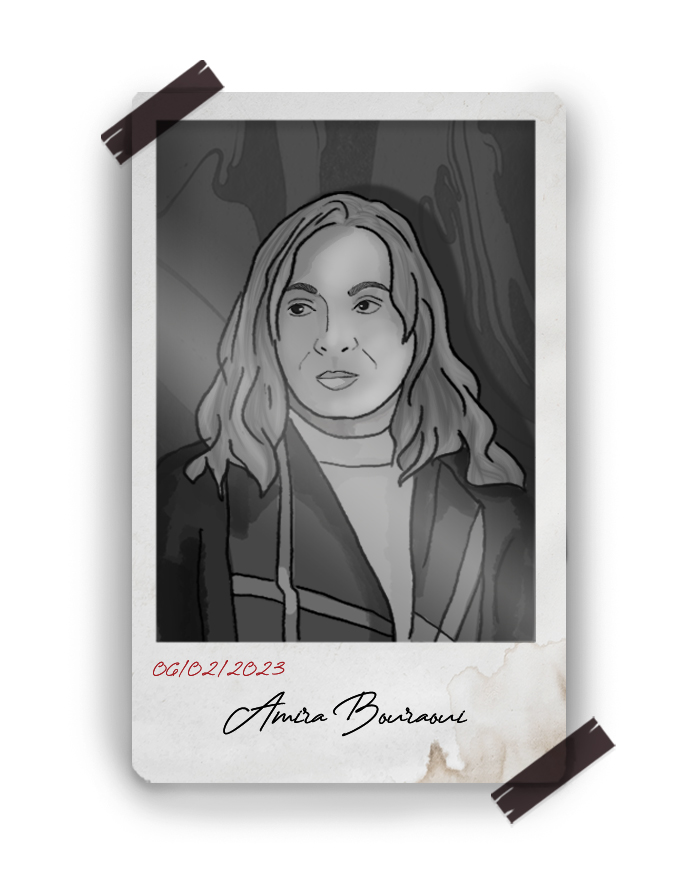

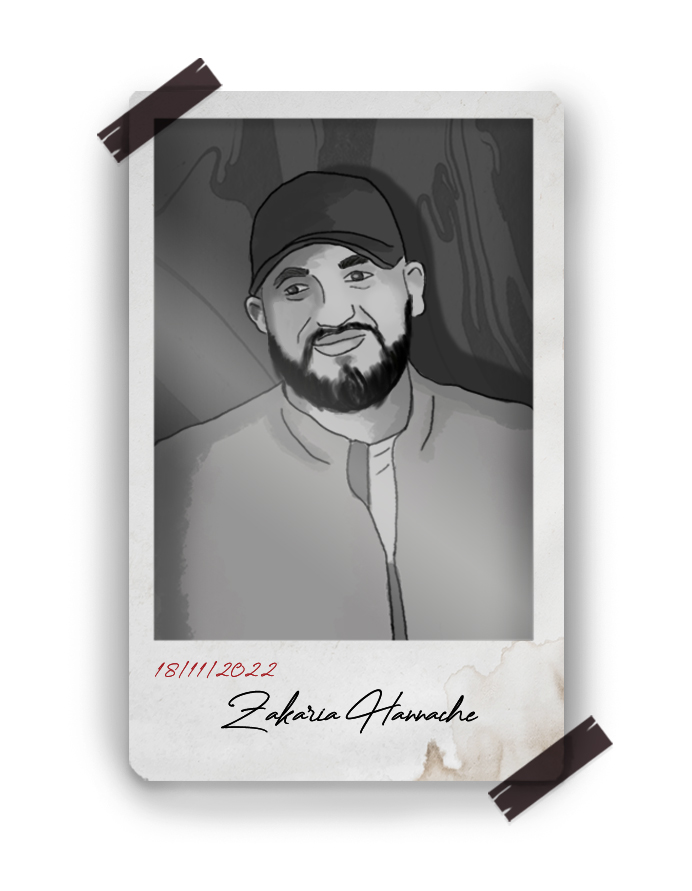

Among them were Amira Bouraoui and Zakaria Hannache, known as Zaki. They called for political reforms and were imprisoned for their views, especially on social networks.

Bouraoui, a former gynecologist and journalist, was detained for ten days in the Kolea prison for "offending Islam" and "insulting the President of the Republic". Zaki Hannache, on the other hand, was singled out for his work in collecting and posting information on the arrests of prisoners of conscience. The human rights activist has been prosecuted in Algeria since 2022 for "praising terrorism" and "undermining national unity".

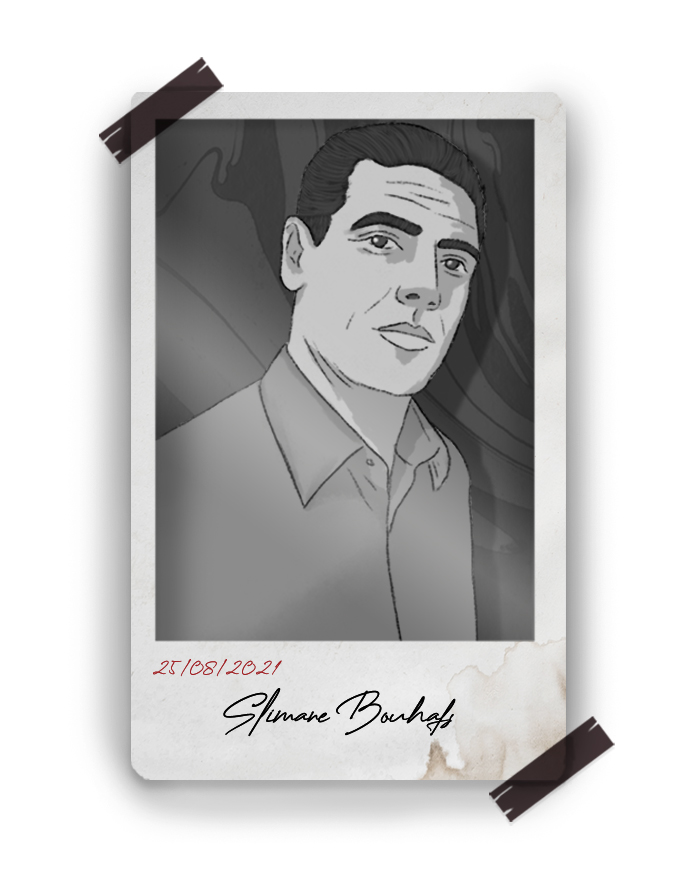

The government did not wait for the Hirak to threaten opponents. In September 2016, Slimane Bouhafs, an Amazigh activist and converted Christian, was convicted of "insulting Islam and the Prophet Muhammad".

Upon his release, Bouhafs took refuge in Tunisia. A few years later, Zaki Hannache and Amira Bouraoui made the same decision. But even though they were far from their country of origin, these activists were still at risk.

Tunisia, a risky transit country

Faced with threats, Amira Bouraoui tried several times to travel to France. But she was refused entry at the Algiers airport on the grounds of a ban on leaving the national territory. At the beginning of February 2023, she changed her strategy and decided to cross the Algerian border using her mother's passport. Her destination was Tunis.

A few days after her arrival in Tunisia, Amira Bouraoui tried to take a flight to Paris from the Tunis-Carthage airport. But the activist was arrested and placed in custody for 48 hours for "crossing borders without legal documents". She was then brought before a Tunisian judge who decided to release her until her next hearing, 20 days later.

But as she left the judge's chamber, outside the Court of First Instance in Tunis, "she was seized, manu militari and abducted" said one of her two lawyers, Hashem Badra. The two officers who took her put her lawyers on the wrong track by telling them that they were taking her to the airport. In reality, she was that she was being held at the Directorate General of Borders and Foreigners.

"My client was being held at the end of a hallway, her eyes were puffy, and she begged us not to give up on her," recounts Badra.

Bouraoui was indeed facing extradition and "the risk was imminent because a flight to Algiers was scheduled for that very evening" according to a source close to the case.

Her lawyers and relatives were made aware of her fate and, along with a number of organizations that Bouraoui had previously informed of her escape plan, alerted the press and contacted the French consular authorities.

Having French citizenship, Bouraoui is eligible for consular protection as a national in a foreign country. Thanks to the mobilization, the activist was quickly taken to safety at the French Embassy before boarding a flight to Lyon at 9 p.m. "Some people acted in parallel to the court order and her extradition was just a few hours away. It's a good thing that the Consulate was so quick to intervene," added the same source.

Refugee, a vulnerable status

Bouraoui was thus able to get consular protection as a French citizen, which was not the case for Zaki Hannache, whose only protection was his refugee status.

It should be noted, however, that there is no protection law or national authority in Tunisia that protects and safeguards the rights of asylum seekers. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in collaboration with the Tunisian Red Crescent, is the sole body that studies these applications and grants refugee status.

In March 2022, Zaki Hannache was detained for several weeks in Algeria and then released on bail. He was still subjected to intimidation and pressure. He went to Tunisia for medical care in August and was granted refugee status by the UNHCR in November of the same year.

Although he no longer lives in Algeria and his activism has significantly subsided, Zaki Hannache is still on the authorities' radar. On March 2, 2023, he was sentenced in absentia to three years in prison and an international arrest warrant was issued against him. A source close to the case suggested that Algeria should promptly send an official extradition request to Tunisia.

In a Facebook post, one of Zaki Hannache's lawyers listed the reasons why Tunisia would be committing a significant number of offenses if it were to grant the extradition request. Indeed, Article 29 of the judicial cooperation agreement between Algeria and Tunisia signed in 1963 prohibits extradition when the crime for which it was requested is considered by the requested State as a political offense.

Additionally, Tunisia has ratified the 1951 Convention relating to the status of refugees, the foundation of the UNHCR's work, whose core principle is non-refoulement, "according to which a refugee should not be returned to a country where their life or freedom is seriously threatened."

"Tunisia has always respected human rights. The country hosts the headquarters of several international organizations. There is no legal basis for my extradition. Tunisia shouldn't give in to pressure", says Zaki Hannache.

Despite the existence of these conventions, Tunisia doesn't guarantee the protection of Algerian refugees on its territory. "The activists and opponents who flee Algeria to take refuge in Tunisia are aware of the close security cooperation between the two countries, which is why they consider it as a temporary place of passage" explained this source.

As such, Zaki Hannache's plan is to reach France, or a country that has an agreement with UNHCR through a resettlement request. "I'm worried that the extradition request procedure is being processed too quickly, when it should take several weeks, and that leaves me no time to find a safer country," he explains.

"A Bouhafs-style scenario"

Slimane Bouhafs' story confirms Zaki Hannache's fears. This activist spent almost two years in prison before being released in March 2018 under a presidential pardon. He then reached Tunisia, where he applied for refugee status from the UNHCR, which he was granted in 2020.

Bouhafs had already been living in Tunisia for several months when he was abducted on August 25, 2021, before turning up in the hands of Algerian authorities a few days later.

He appeared before an Algerian court in September 2021 for alleged links to the Movement for the Self-Determination of Kabylie (MAK), which Algeria considers a terrorist organization. Convicted on six terrorism-related charges, Bouhafs is currently being held in the Kolea prison pending trial.

Over a year and a half after his abduction, the case of Slimane Bouhafs is still fresh in people's minds. Although he was granted refugee status, the former police officer had expressed a number of concerns about his safety, as he felt threatened and followed. A number of associations and organizations denounced his abduction and the conditions of his disappearance on Tunisian territory.

To address the collective outrage, Tunisian President Kais Saied announced in September 2022 the initiation of a "thorough investigation into the circumstances of the abduction," but so far, no results have been presented.

"Unfortunately, the Tunisian authorities have been rather complacent in their handling of the Slimane Bouhafs case," noted a source.

Several experts believe that the socio-political climate in Tunisia, particularly the fragile independence of the judiciary, could serve Algeria well if the country wanted to launch an operation to forcibly repatriate Zaki Hannache, in the same way as Bouhafs.

"The Algerian regime likely resents Amira Bouraoui's recent escape. The police and legal machine is set in motion with a logic of escalating repression," said a source close to the case.

"Algeria is also showing a willingness to act against people in the diaspora, in a logic of transnational repression," according to the same source. As the Bouhafs case has shown, and given the importance of cooperation between Algeria and Tunisia in many sectors, such as energy and security, Algerian refugees abroad are also at risk of being arrested.

Another source was more optimistic. They believe that Algeria has nothing to gain by forcing Tunisia to extradite the opponent: "He is exactly where they want him, as long as he's no longer talking and has stopped his activities of reporting political arrests in Algeria."

While awaiting the outcome of the Hannache case, the Algerian authorities are intensifying their pressure on their own territory. Following the escape of Amira Bouraoui, her mother was placed under judicial supervision and a dozen of her alleged accomplices were placed in pre-trial detention.

These people include the journalist Mustapha Bendjema, the cab driver who transported the opponent, and a border police officer. They are being prosecuted by the Constantine tribunal for "criminal association with the purpose of carrying out the crime of illegal immigration as part of a criminal organization" and are awaiting trial.