Upon entering the courthouse, one has to go through a security check where it is up to you to place your bag under the scanner which is meant to detect suspicious objects, supposedly under the supervision of a young policeman who usually stands somewhere nearby, either absorbed in his phone or in conversation with a colleague.

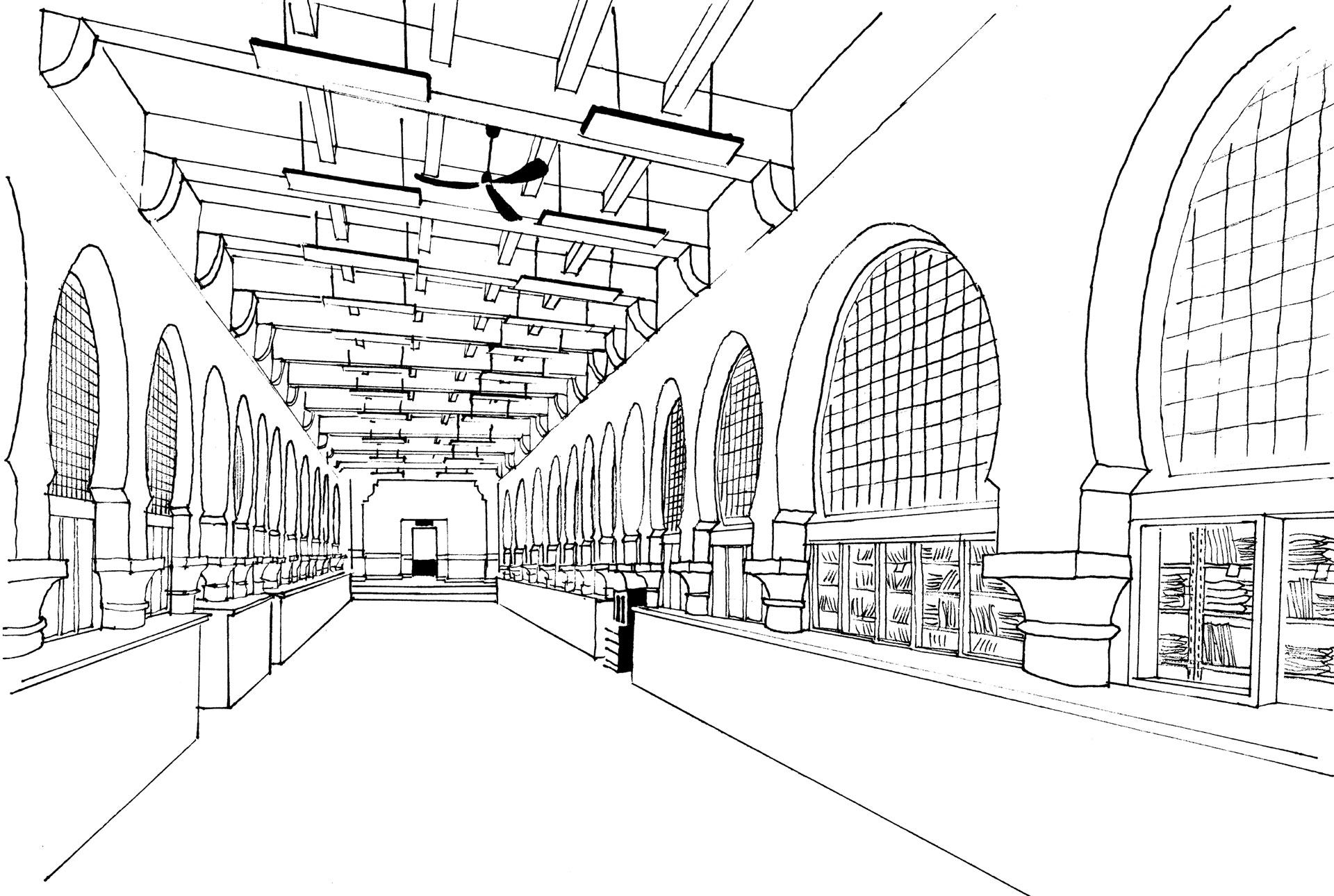

Completed in 1900, the impressive building was designed by French architect ‘ Jean-Emile Resplandy’ who introduced the style of Art Nouveau to Tunisia. It was constructed combining the styles of Beaux-Arts and Arabic architecture. As you enter the building, you find yourself facing a majestic staircase that leads you the first floor. From the top of the stairs, a few steps to the left is all it takes to be thrust into a bustling hall where the archive as well as the employees seem to be in eternal purgatory.

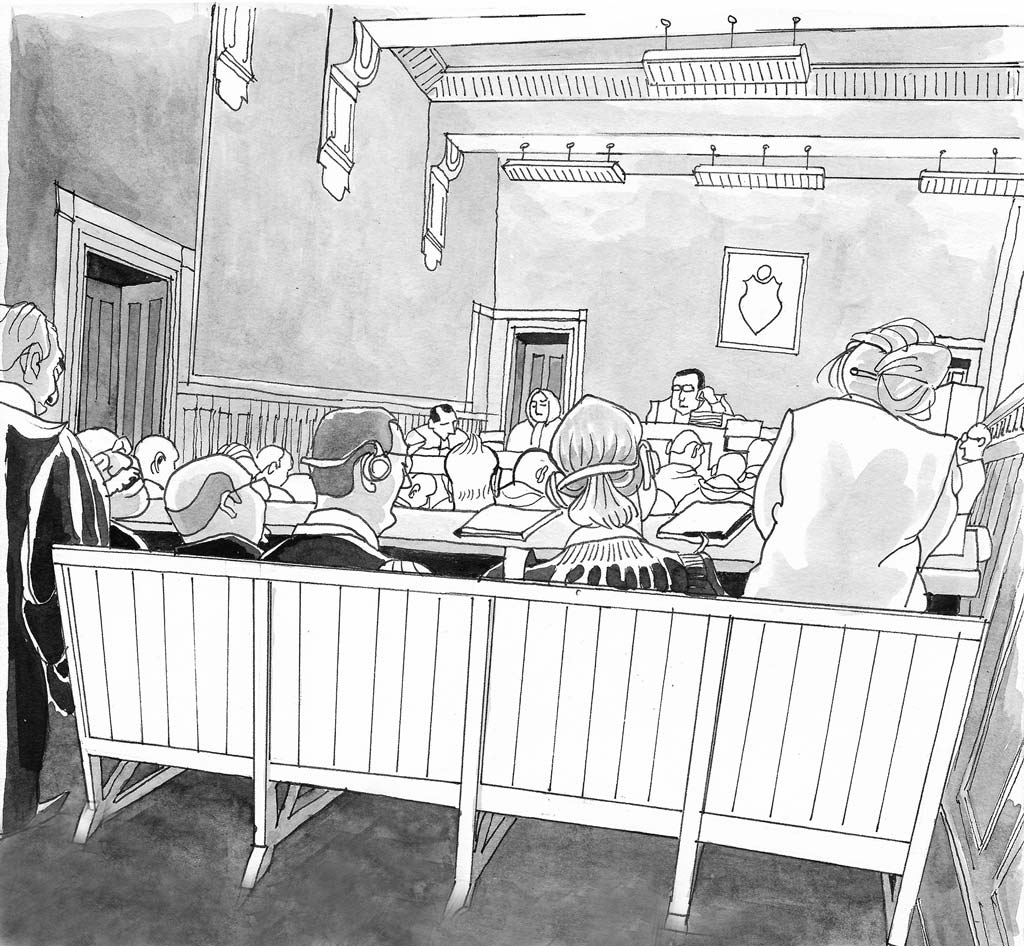

After only a few more steps, you find yourself in front of courtroom No. 6. It is behind the worn-out wooden panels of this courtroom that terrorism trials take place every Tuesday and Friday. In fact, it is within these few square meters that the largest number of terrorism cases in the world are tried. Between September 2015 and June 2018, 4572 cases were tried with 1804 suspects under arrest.

The Parade of the Accused

Judge X is one of the judges appointed to the Antiterrorist Pole of Tunis. For security reasons he requires to remain anonymous.

Every week during these two days, the same gathering of people happens in the exact same manner. Families - who have often undertaken long journeys to watch their son, daughter, brother, or sister be accused – impatiently wait to see the face of their accused relative. The narrow benches are packed with bodies squeezing closer and closer with every newcomer. The first row of benches facing the judges is reserved for lawyers, often seen pulling out thick case files or repeatedly entering and exiting the room.

The door creaks and then slams. The judges arrive, usually at 9.30 am. The clerk sits on the left. The Prosecutor sits on the right. In the middle, three judges are seated, including the president. Only the latter speaks, and the accused can enter. Escorted by the guards, the accused all line up on the empty benches facing the court.

Since the charges are not public, the prosecutor does not utter a single word. There is no indictment list. The case file is only placed in front of the president, the content of which everyone except the lawyers will know next to nothing about. Another noticeably strange element is that all of the accused are brought in together, even when they are not involved in the same case.

They sit quietly on benches that resemble school chairs, their eyes trying to meet those on the other side. Behind the row of lawyers, the relatives often gesture to which the accused responds with a discrete smile as if saying “ yes… yes… all is good", with a combination of pride and joy of seeing a familiar face.

These hearings would scare away even the most tenacious onlooker or judicial journalist, and have indeed seemingly exhausted their patience since I have not seen them in the courtroom over the years.

So why this feeling of sadness? First of all, there is a sense of bitterness in seeing hundreds, even thousands of people at an age where they should be studying, falling in love and getting jobs, condemned to spending their youth in a dark dungeon. After attending a few hearings, one is inclined to reason that many of them have simply lost their way.

After several hundreds of hearings however, one starts thinking that the real problem is the society that we are brought up in, given the severity of the phenomenon.

Were the accused aware of the fact that this was merely the beginning of their ordeal? They were facing the purgatory of several years in prison: 5 or 10 or even more for any ideological affinities with Islamist groups. Then, if they were ever released from prison, hell was awaiting them on the outside. These wer thee things that came to mind during the long hours of trials.

In addition to this bitterness over wasted youth, there is frustration over the fact that the real culprits remained absent throughout the months of hearings. Where were those conquering tenors of Jihad and divas of Wahabism? Those Al-Qaida and Jabhat Al Nosra intellectuals in vogue? Those bearded military right-wing extremists and radicals?

They were not here. The Jihadist aristocracy generally shuns trials. The majority were imprisoned abroad, deployed in warzones, dead in combat, or killed by drones. As for the rare few leaders on Tunisian soil, a more severe type of trial was awaiting: that of the military court.

Those who remained in Tunisia were most of the time secondary players: dissatisfied returnees from warzone experiences who were unaware that Raqqa would not be like Ibiza before leaving; some Ansar Al-Charia militants after banning the movement in 2013; vaguely awakened sleeping cells in popular neighbourhoods and their support networks who brought phones and gas tanks, or preached at or frequented a radical mosque or a jihadist 2.0 page…

One after one, they took their places on the benches of the accused. The president intentionally addressed the accused in a voice that was barely audible. Most of the time, the voice was just low enough not to be heard by the audience or the lawyers who repeatedly complained about this obstructing their work. Annoyed, the president would proceed to asking questions, his eyes fixed on the mechanically turned pages of the case file.

Case upon case is dealt with in a rapid and business-like manner, distracting us from the terrible melancholy of it all. The severity of the cases stood in glaring contrast with the simplicity of the people accused: the case of Fatma Zouaghi,* the attack

of Ben Guerdane, the attack of Mnihla.**

The heavy monotony of the hearings was sometimes abruptly derailed by an unexpected turn of events. Sometimes this would be funny, like the time when the president asked the accused about the initial reasons for their involvement.

“I wanted to go to paradise.” “Well did you eventually find it? If so, would you be please lend me the keys?” Everyone in the courtroom burst into laughter.

Another time, the accused was a large, bearded man with the archetypical physique of a fighter, weighing over 120 kg in muscle. ”Why did you go to Syria?” “I was interested in ancient architecture…”Once again, a simple phrase had quite an impact.

Other times, the trials were pitiful. I will never forget the day where the accused: a barely 20-year-old girl concealed under her niqab, passed out from the pressure of the trial. As a policewoman rushed to help her, the man behind me started crying. Aged 70 or 80 years old, the man was her father.

The girl was taken outside, the trial postponed. From one end to the other, the old man kept pacing up and down the empty hall, his worn-out shoes revealing some of his toes. Unable to fully understand the situation, he impatiently waited for his daughter, thinking that he would leave with her. He was unable to understand the gravity of the situation. He had simply come thinking he would pick his daughter up from the courthouse.

Unlike the European system where an investigation must be concluded before holding a trial, Tunisia’s legal system states that the trial can and must commence within 14 months, which is the maximum period of pre-trial detention.

This was emotional torture for the accused and their families. Every time there was a missing document or a new request from the judge or the lawyers, the trial had to be postponed for several months. The detention in this case would last years before reaching a final verdict.

The Defence speaks

Toward the end of the process, the defence attorneys began their arguments. We often see the same group of lawyers sharing all their files on cases of terrorism. Many of them started out in the Association of Freedom and Equity, an association affiliated with Islamism and which defended political prisoners under Ben Ali.

Almost all of them had Islamist affinities. As for leftist lawyers, they avoided taking on cases of terrorism after several blood crimes and the assassination of their fellow colleague Chokri Belaid in February of 2013.

“I believe that every defendant has the right to a lawyer.”

Imen Triki is one of the leading lawyers in Tunisia for jihadists and their families. A human rights activist, she was also president of the association of Liberty and Equity between 2011 and 2014.

Other lawyers, unlike Imen Triki, would accept to defend the alleged jihadistst acknowledging the “ value” of their cause, but reject blood crimes. This was notably the case of Anouar Ouled Ali.

“I had my reservations about certain cases, like murder cases.”

Anouar Ouled Ali is one of the main defence lawyers of jihadists and their families in Tunisia. He also heads the association “Observatory of Rights and Freedoms” in Tunisia.

For many cases, the lawyers cite procedural flaws or exploit weaknesses of the prosecution’s case file. Many cases are actually based on confessions that according to the lawyers and the accused were usually extracted under torture.*

The right to a defence has generally been respected since the revolution. In fact, the new antiterrorist law of 2015 has shown notable improvements, even if some of these have been criticized.* One of these improvements included the presence of a lawyer starting from the very beginning of detention. However, the general prosecutor can revoke this presence during the first 48 hours, a measure that was denounced by lawyers.

While the right to a defence is respected, the rights of the accused are not, particularly during the arrest and the initial interrogations held within the first 48hours of detention. 48 hours must have passed before transferring the accused to a judge or the Antiterrorism Pole, whereupon it will be decided whether or not to file charges against the accused based on confessions and investigation. Spent at either Gorgani or L’Aouina,* the detention duration of 48 hours leaves little time for police officers to extract confessions.

“In most cases, the suspects end up retracting their confessions.”

Judge X is one of the judges appointed to the Antiterrorist Pole of Tunis. For security reasons he requires to remain anonymous.

A justice system under police pressure

Ten years after the fall of Ben Ali, the Ministry of the Interior remains one of the institutions resistant to reform. At that time, the police made the decisions and the judges obeyed. Tunisia has gone through a lot of changes since then, but old habits die hard.

“The police don't understand that they cannot continue using the same old methods […], and that they can’t expect the judge to convict people using incomplete case files anymore.”

Lawyer and former opponent of Ben Ali, Samir Ben Amor was elected as deputy of the Constituent Assembly in 2011 (under the label CPR of the Tunis 1 constituency), after the revolution.

Security forces, particularly those targeted by terrorist violence,* found it difficult to accept certain legal subtleties. Tensions ran high between the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Justice over methods of antiterrorism.

“The police arrest and the judges release”, one could hear security forces saying.

The judges on the other hand could not prosecute or convict suspects on the basis of weak confessions, extracted within a matter of hours and under suspicious conditions.

“After announcing the verdicts, some judges would receive threatening letters to their homes.”

Judge X is one of the judges appointed to the Antiterrorist Pole of Tunis. For security reasons he requires to remain anonymous.

The tension between security forces and the justice system would sometimes take a turn for the worse, perhaps the most nationally notable case being the Museum Bardo attacks.

A quick reminder: On the 18th of March 2015, sometime after midday, two heavily armed men entered the Tunisian capital’s most famous museum and began shooting tourists. Outside, there was very little security: only one single officer with an old pistol, unable to put up a fight against weapons of war.*

The terrorists managed to kill 22 people in cold blood as well as injuring 45 others before being killed themselves by the Antiterrorism Brigade (BAT) shortly after arriving at the scene. The country was in shock, as these were the first attacks against civilians since those of Ghriba in 2002.

The affair soon became political. The attack was a painful blow to the tourism sector* with almost all of the victims being foreigners, leading to foreign countries, the press and the public demanding answers and retribution.

However, the ahead of the attack, the Bardo Police Station had asked for reinforcements for the following day, only to be refused by the Ministry of the Interior. The state consequently had to react quickly, and president Beji Caid Essebsi held a press conference the following day.

Meanwhile, an infernal cycle was set in motion: political pressure on security forces and security forces pressuring the justice system, pretty soon the investigation got out of control. Two days later, the name of a young man without any previous criminal record, “ Amine”, was announced in the media during a press conference held by the spokesperson for the Ministry of the Interior.

The Gorjani judicial police officers (OPJ) arrested more than twenty people. The minister of the interior Najem Gharssali himself announced this news to national and international media on the 26th of March, only 8 days after the attacks.

In reality, the people arrested had nothing to do with the attack. Having been violently tortured, and sometimes raped, they ended up signing confessions written by the police.*

Located on the first floor of the courthouse (a magistrate would be able to attest to this), he was the controversial judge in charge of the Bardo attack investigation. Today, Béchir Akremi is the General Prosecutor of Tunis in charge of antiterrorism.

To find him, one has to ascend the big, central staircase, and get lost in the narrow halls leading past handcuffed suspects and lost faces searching for the courtroom for divorce.

Judging by the number of the files placed methodically on the tables, Béchir Akremi’s office (the window of which looks over Boulevard 9 Avril) seems like it has not seen the slightest bit of daylight since the building’s construction. A pack of lawyers and judges create a constant flow in and out of the office, all of them immediately received by Akremi - but no journalists. This is the first time that he accepts a request for an interview.

“They applied torture... and what is more, the contents of the interrogations were contradictory.”

Béchir Akremi, Investigating Judge in charge of antiterrorism, appointed General Prosecutor of Tunis in 2016.

The twenty people arrested were released six months later, having found no proof of their involvement. These men and women were not presented with any public apology or compensation. Judge Akremi was himself accused by certain media of having affinities with Islamist movements. Some lawyers of victims in France publically objected to his decision.*

"At first, people were wrongfully arrested in connection to the Bardo attack."

Philippe Dorcet, former examining magistrate, turned president of the Court of Cassation in Nice. Currently the French liaison magistrate at the French Embassy in Tunisia.

Meanwhile, the case took a political turn costing the interrogation precious time, as the people who were truly behind the Bardo attack were free to coordinate new ones behind the scenes. The next turn of events was the Sousse attack where 39 tourists, most of them British, were killed in a machine gun attack in a hotel.

“The arrest of several suspects involved in the Sousse attack began to reveal what had been unfolding in Tunisia since 2012, including the sources and people involved in arms trade.”

Béchir Akremi, Investigating Judge in charge of antiterrorism, appointed General Prosecutor of Tunis in 2016.

The case exemplifies the dangers of justice under pressure where no one has either the time or the means necessary to accomplish their task. The trial would first begin nearly 3 years later. Meanwhile, it became clear that this complex international cooperation was full of pitfalls and proven to be chaotic.

When the Bardo-Sousse trials began on the 25th of January 2019, it was in the all so familiar courtroom No. 6, but this time with a revamped atmosphere. This time, the press and onlookers were present, and the hearings were broadcast to the families of victims in France and Belgium. This time, the president of the court could be heard clearly, talking into a microphone.

The first plead by attorney Zagrouba began as follows:

“It is with great pain that we see children of this country being judged by thousands due to the political policies of powerful authorities. To those who are attending the trial in Paris, the defence greets you with the following words: He who plants thorns will reap wounds.”

The defence attorney had just directed our attention toward another political arena. Perhaps this was what set the scene for the following, uneasy trials. His words were polemical, even questionable, he knew this – but they also voiced what many of those sitting in the courtroom were already thinking…