The young man is originally from the Casamance region of Senegal, where government forces have clashed with the main separatist movement, the Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance (MDFC), since 1982. The civil war has resulted in hundreds of casualties, including Djibril’s father, who was killed in 1999.

The departure

After his father’s murder, Djibril’s mother moves him and his younger brother to the Gambia. Djibril is a teenager at the time. “I was a technician there. I learned a trade in the field of cooling – refrigerators, air-conditioners, washing machines,” he lists. Once he finishes his training, he opens up his own workshop and is the sole breadwinner for his family.

In 2016, protests erupt throughout the Gambia. The protesters demand for president Yahya Jammeh to step down and for his political prisoners to be freed. The government cracks down with heavy repression, arbitrarily arresting and torturing protestors. Djibril loses a friend in the violence. “ They take people away, imprison them, and then nobody comes back,” says Djibril.

“ We don’t even see their graves, there is no trace of them . . . the only choice you have is to leave the country.”

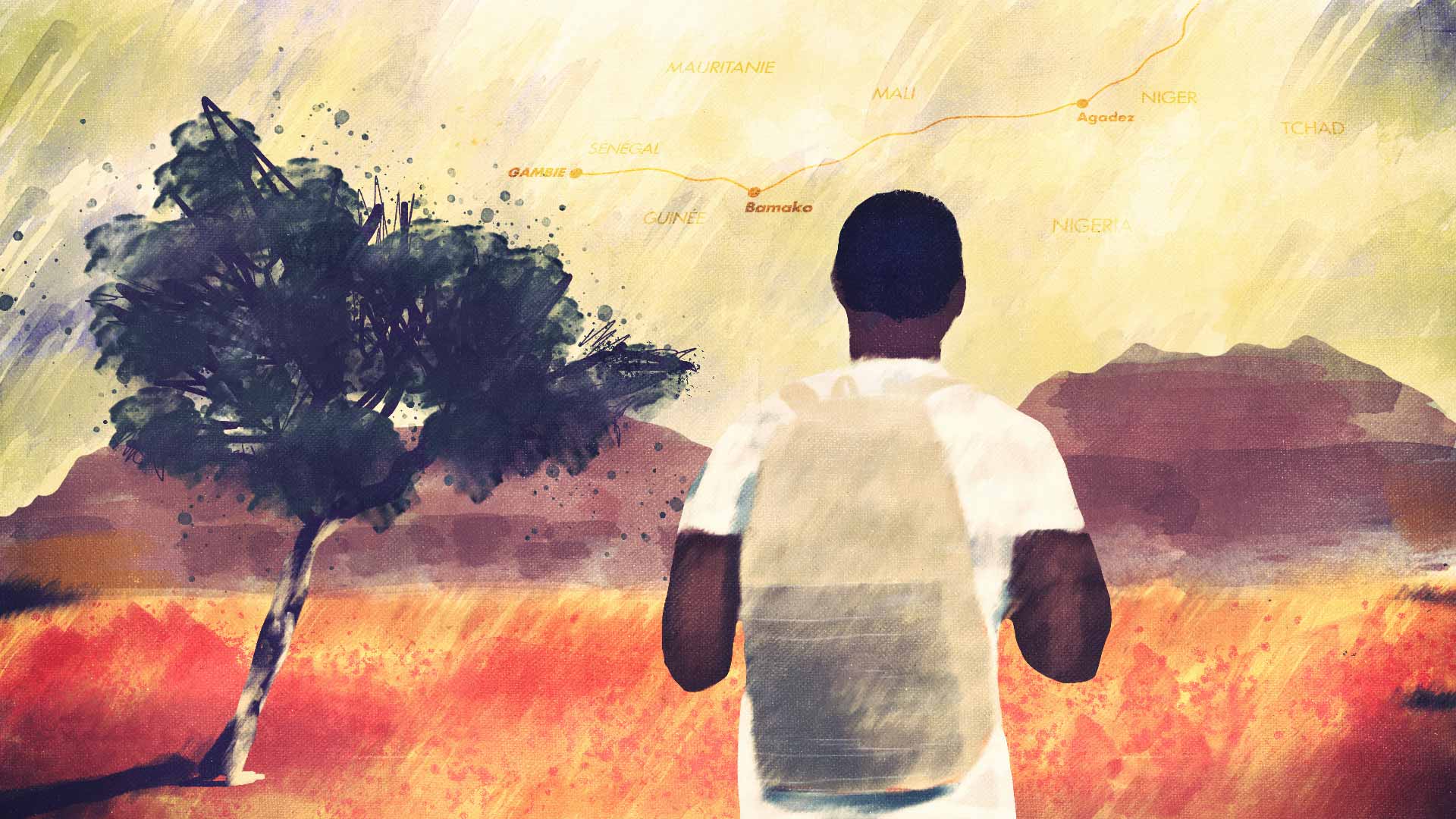

On August 15th, 2016, Djibril sets off for Europe. For him, this is the only way to find “ tranquility and peace” and exercise his “ freedom of expression.” He gathers all of his savings, leaving one year’s rent for his mother and brother, and heads towards his first stop: Bamako, Mali.

Crossing the desert

Initially, the young man plans to cross through Morocco. Like many other migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa, he hopes to reach Europe through the Spanish enclave of Ceuta or by crossing the sea via the Strait of Gibraltar.

But in Bamako, he comes across migrants who advise him against this path. “ They told me, ‘No! You will waste your time in Morocco! It’s faster to cross through Libya!’” Djibril recounts. Most of these people were, perhaps unknowingly, propagating stories from smugglers profiting from Libya’s ever-growing trafficking hub.

And so Djibril follows their advice and heads instead to Agadez, Niger’s capital. He prepares himself “ to cross the Sahara.” He finds himself in the back of a pick-up truck with 31 other people packed in “ like sardines in a can.” Without space to sit, the passengers cling to each other to stay standing. Djibril’s pickup is one of six vehicles in a convoy moving towards Sebha, a town in the heart of the Libyan desert.

After three days on the road, Djibril’s pickup breaks down in the middle of nowhere. “ It is there that things got complicated,” says the young man. The driver asks the 32 migrants to guard the vehicle as he drives off in another car, promising them that he will search for a mechanic and return quickly.

The smuggler never comes back for them. The group stays in the same spot for three days, quickly depleting their water reserves. “ At this point you don’t think about eating,” says Djibril, “ You only think of water. That’s your problem.” On the third day, convinced that no one is coming back for them, he decides to leave the group, alone.

“ If I have to die, it is elsewhere, not here,” decides Djibril, “ I can’t wait anymore.” Djibril wanders for a day and a half in the desert, without any food or water. “ I drank my urine,” he says. He is exhausted and his feet burn from the heat of the sand.

Two days after he left the group, Djibril hears the sound of cars and hurries towards it. “ I shouted! And they arrived just next to me, thank God.” He finds another convoy on its way to Agadez.

Prison

This second convoy picks him up and takes him through the desert to Ubari, a town near Sebha, in southeastern Libya. Once they arrive, the smuggler demands that Djibril pay for the trip. Djibril tries to explain that he already gave 225,000 CFA francs (around 1,000 Tunisian dinars) to the first driver, but the smuggler has no remorse. “ I was tired, I wanted to sleep . . .” says Djibril with a sigh, “ but they put me directly in prison.”

“ There, they torture you with a stick, an electric one. They burn you with plastic. That is prison in Libya. They burn you.”

Finally, Djibril is handed a phone so that he can call on a friend in Gambia to transfer 350,000 CFA francs (around 1,560 Tunisian dinars) to a bank account provided by the smuggler. With the help of Djibril’s family, his friend manages to gather the requested sum and Djibril is released after seven days of detention.

He leaves for Sebha, along with a number of other migrants. As soon as they arrive, they are thrown into another prison where the conditions are “ even more difficult.” Every day, the detainees receive a piece of bread and a small can of water, which they also used for their bodily needs. “ Where you sleep is also where you shit, and where you urinate, and where you eat,” Djibril describes with disgust.

Small cells sometimes hold more than 45 people at a time. “ They’re like the living-dead. The people there, they don’t have anything to eat, no water to drink, nothing” says the young man. Djibril sees how the “ mafia groups” running the prison systematically detain migrants in order to extort money from their families. This time, he refuses to pay.

With a group of other prisoners, he decides to escape. “ We decided that we would not sleep there that night.” The group waits for when the guards arrive to give them water. The moment that the doors open, they attack. “ I was lucky,” exclaims Djibril, “ others died or lost their legs.”

Once outside, they hide all night. When the sun rises, Djibril and the others escape to travel to another city. They leave for Birak, between 40 to 50 kilometers from Sebha. Once there, they manage to find a place to stay.

The migrants find a moment of relief in Birak. “ In Birak, there was peace. There were kind people. You didn’t hear the noises of kalashnikovs, or anything.”

Reaching Sabratha

But Djibril is eager to get across the Mediterranean. Eid al-Kebir is approaching and he dreams of celebrating it in Italy. Following several days of negotiations, he and his friends reach an agreement with a smuggler: he will take them to Sabratha, in the north of the country. “ We were happy!” he remembers, “ We thought that we would celebrate Tabaski [Eid al-Kebir] in Italy . . . we didn’t think that we would stay here long.”

The smuggler, who had been described as “ very kind,” disappears after taking their money. For one month, the group of migrants stay in Birak and try to track him down, without success. To survive, they beg and transport crates to the market for one or two Libyan dinars per day. “ We ate onions and rotten tomatoes,” Djibril says, “ We spent Tabaski there. It was the worst Tabaski of my life.”

The smuggler finally returns at the end of September. He gives many excuses: the driver wasn’t responding . . . the route wasn’t secure. Djibril can finally leave, along with a group of about 40 people.

This section of his journey was “ the most difficult:” more than 500 kilometers, entirely through the desert. “We did not touch tar,” says Djibril. After two days, the pickup comes to a stop. The group is convinced that they have reached Sabratha; but they have actually landed in Nasmah, still 250 kilometers away.

The group is escorted to a large garage with “ over 1,000 people” crowded inside. The armed guards enforce silence by shooting rounds from their Kalashnikovs into the air. The migrants aren’t allowed to speak, but they can whisper. They sleep on the floor.

Djibril and his friends stay in this garage for four days. They call their smuggler several times. On the third night, the smuggler promises them that a car will pick them up during the night to take them to Sabratha. The migrants force themselves to talk so as not to fall asleep: “ Otherwise, the car will leave you here.”

The car arrives that night, but there is not enough space for everyone. Djibril hurries to get into the car, but there are already 20 people in front of him. He is too late. As tensions rise, a guard shoots into the air, tells the migrants it’s in their best interest to keep quiet, and leaves.

In the morning, another car arrives to take them to Sabratha. Djibril gets in. Without knowing it at the time, he was luckier than those who left in the first car. A few days later, he learns that those who left during the night were sold “ to the slave market.”

The regurgitating sea

Two months have passed since Djibril left the Gambia. On October 8th, 2016, he finally arrives to Sabratha, where he is taken to an overcrowded camp nicknamed Campo Bahar (the Sea Camp).

“ Even garbage cans are more beautiful than our toilets there,” Djibril says cynically.

Still, the young man feels optimistic because now only the Mediterranean Sea is left before him. He negotiates with a smuggler and they agree to leave the following day. Now all too familiar with the smugglers’ false promises, Djibril still pays him the money upfront.

Two weeks go by, and Djibril is still waiting in the filthy camp. In the late afternoon of October 23rd, the smuggler gathers a group of migrants. " Today, God willing, you will travel,” he tells them. That night, the boat sets off for Italy.

After several hours at sea, Djibril suddenly hears cries and the sound of gunfire. The Libyan coast guard is pursuing them. Djibril is thrown into prison for the third time.

This time, he is told that he will be sent back to his country of origin if he doesn’t pay a fee. So once again, Djibril calls on his friends and family to send him money (around 1,400 Libyan dinars). He is released after three weeks.

Despite his many setbacks, Djibril wants to try to cross the Mediterranean again. He returns to Sabratha, finds another network of smugglers, and gives them the equivalent of 700 euros. The departure is scheduled for December, which makes Djibril pessimistic. “ The weather was bad and people were saying that the boat was leaking, but we went nonetheless.” The boat sets off, but after a few hours the captain decides to turn back; the crossing is too dangerous. Once back on land, Djibril is thrown yet again into a “private” prison, where he remains for about 10 days.

He spends a difficult winter in Sabratha. “ We went through trash to collect cardboard and plastic . . . that’s how we lit our fires.” Djibril expects to wait until the following summer to try crossing again, but in February 2017, capitalizing on mild weather, he joins a Malian smuggler and boards another boat.

But once again, the coast guard catches them. This time, he is taken to a prison in Sorman, 15 kilometers from Sabratha. “ It was the worst prison I’d seen in Libya,” Djibril recalls, “ it looked like a butcher room.” The detainees are regularly tortured in rooms with “ blood-stained walls.” But what is most shocking to the young man is how the women are treated: they are routinely raped. He does not want to give more details. He can only say, with a shaking voice, that he feels “ sorry for them.”

" It’s even more complicated for them than for men. Because they only need money from us. But with women, it’s complicated . . .”

Djibril stays one month in this prison. For the umpteenth time, he contacts his family, and they spend the last of their savings to free him. “ I did not have any more money at this point. So I had to find a way to work.” He decides to go to Zouara, about 50 kilometers away.

There, he meets a group of migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa who, like him, are working to finance their trips across the sea. Djibril finds work as a hairdresser and after three months earns the 1,500 Libyan dinars needed for his next attempt.

In May, he takes himself back to the camp in Sabratha. And at the end of the month, he boards a boat, called the Zodiac, along with another hundred people. This time, they are not intercepted by the coast guards, but they do run out of fuel part way through their third day. “ We were waiting for death.”

The Zodiac drifts off course for many hours. In the early morning, they are spotted by Tunisian fishermen. At that point, in international waters, the passengers still hope that they can reach Italy. But the Tunisian Navy comes to save the passengers and brings them to the port of Zarzis, a town in the south of Tunisia.

Djibril’s voice shakes as he recalls these events and what happened to Rose-Marie. “ The boat didn’t sink, but there was a girl with us called Rose-Marie, she was seriously ill, she couldn’t take it any longer . . . She died on the boat. She is the only one who died.” Rose-Marie was buried in the migrant cemetery in Zarzis that was built by the citizens of the town. She is the only person buried there whose name is known. She was 20 years old.

And now?

Djibril arrives in Tunisia on May 27th, 2017. He is placed in the Red Cross center in Medenine, where he stays for three months. “ I couldn’t sleep because of the stress. I couldn’t eat. A bit of water, Nescafé, cigarettes. Too much stress. I lost all of my money in Libya.”

In Medenine, Djibril finds it difficult to do simple activities: walk in the streets, socialize with other people. For many weeks, he stays closed in his room. One day, the director of the center suggests that Djibril move on to Zarzis to “ change the air” and eventually to look for work.

In Zarzis, Djibril is able to live in a small apartment. He smokes cigarette after cigarette. He also paints, especially during the night as he battles his insomnia. Painting helps him to make “ beautiful things.” “ During the night, while everyone is sleeping, at least I am doing something.”

Djibril doesn’t see himself staying in Zarzis. “ I never imagined that I would be in Tunisia one day!” His laugh is forced. In Medenine, he contacts the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to seek asylum in Europe, but his request is denied. He isn’t surprised. According to him, organizations such as the UNHCR do not know anything about the realities that rejected asylum seekers face in their countries of origin.

At this point, Djibril plans to contact the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) to start the procedure to “voluntarily return” to the Gambia. “ I suffered a lot for the Mediterranean, I tried many times, I went to prison . . . it is enough now.”

If he returns to the Gambia, he hopes to use his story to warn young people hoping to migrate, especially of the risks within Libya. Through his experience, he has realized that people wishing to migrate are not aware of the violence that awaits them.

“ He lost his voice, his value, his dignity. Why? . . . Because I wanted to go to Europe.”

Above all, Djibril wants to see his mother. More than once, she was told that her son had died. “ She was told that I drowned, that they killed me in prison.” These shocks impacted her health, which was already fragile. “ I have to go back. I want to see my mother while she is still alive."