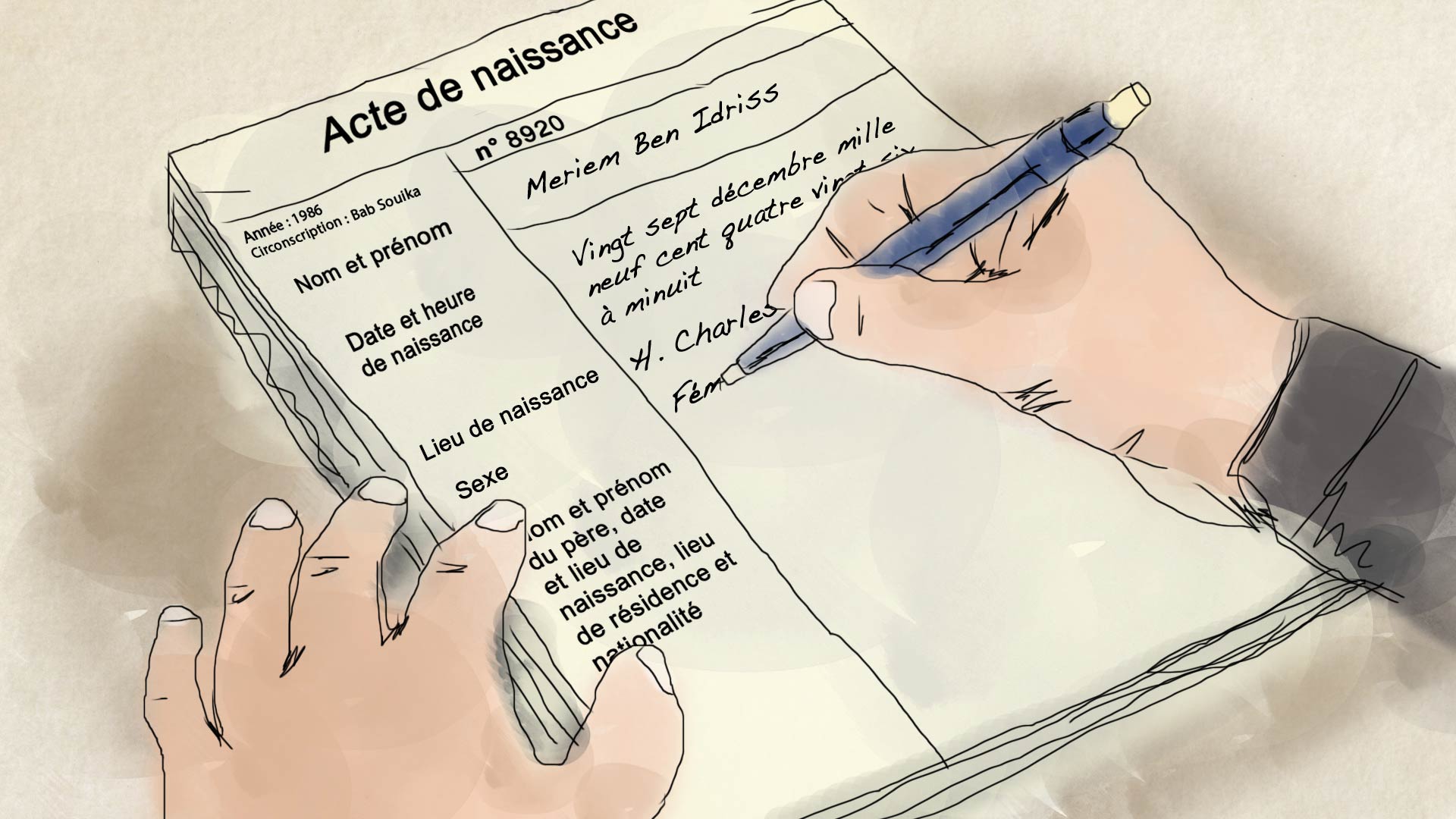

Meriem Ben Idriss’ birth certificate — no. 8,920, register no. 30, municipality of Bab Souika — indicates that her father, I., was Tunisian and her mother, R., Bulgarian. Apart from this reference, there is no other information on Meriem’s mother in Tunisian civil records. Her alleged father, on the other hand, does appear in other records.

The Childless Father

I. Ben Idriss was born in 1953 in the governorate of Bizerte. According to statements provided by his family to criminal investigators on May 26th, 2015, I. Ben Idriss had suffered from severe mental disabilities since birth. He never obtained a national identity card or passport, nor had he even once visited Tunis. According to his death certificate registered at the municipality of Bizerte, I. Ben Idriss died in 1987, a short while after the alleged birth of Meriem Ben Idriss. His family claimed that he had never married or had any children.

The truth is, Meriem Ben Idriss was part of an elaborate story crafted over many years by Russian diplomats. She never existed.

To understand how “Meriem” was created, one should refer to the case of Mourad, the head of the civil registration office at the municipality of Bab Souika. Mourad was arrested in May 2015 after he was found guilty of taking part in a Russian espionage operation. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison in November 2017.

Russian diplomats and Tunisian civil servants

Mourad has his first encounter with a Russian man named Mikhaïl in June 2010. Mikhaïl had stopped by the Bab Souika municipality in search of a birth certificate. As Mourad testifies before an investigating judge, he recalls how Mikhaïl came back to his office two months later and how not long after, the two were meeting for coffee in La Marsa or lunches in La Goulette.

During these meetings, Mikhaïl is eager to learn about the civil servant’s work, and he is generous in return, offering Mourad a “little financial assistance.” As the year progresses, Mikhaïl’s general questions turn into precise requests. For “ administrative reasons,” Mikhaïl wants to access the birth certificates of his Tunisian employees, at least for the three that were born in 1986. He is also interested to know what types of pens are used to write data into the civil registers. Why? Mourad never asks. According to him, all that transpired between he and his Russian friend is “legal.”

Then, in June 2013, Mikhaïl disappears, taking with him at least eight birth certificates dating from 1986, as well as Mourad’s Tunisian passport. Before disappearing, he presents Mourad with “ a surprise:” his friend called “Karim.” Karim is also Russian, but he has the advantage of speaking Arabic . . . with a Lebanese accent.

Mourad feels at ease with Karim from the start. As he did with Mikhaïl, Mourad meets Karim for meals; buys him a SIM card, because he is too busy to do it himself; and slowly starts providing him with documents, many dating from 1986. The only difference is that Karim asks for birth certificates in their original form — as they were at the time of issuance. “ It was for a sociological study,” recalls Mourad who, until then, agrees to provide the requested documents.

But Mourad has his limits. When Karim asks him for a civil register from the year 1986, he refuses to provide it: “ it was illegal.” Karim doesn’t insist and gives him 150 dinars nevertheless.

In March 2015, Karim returns with a new request. He mentions that he could not find a person by the name of Meriem Ben Idriss, born in 1986 and registered in Bab Souika, in the Tunis digital database and inquires why. Mourad promises to look into the matter.

How to register a birth from 19 years ago?

Back at the municipality, Mourad enters the room where the birth registers are stored. As the head of the civil registration office, he has special access to this area. During his hearing before an investigating judge, Mourad confirms that he found the birth certificate of a Meriem Ben Idriss. Her birth, no. 8920, was the last entry in the registers of 1986. But the question remains: how was she integrated into the system?

Mourad had never dealt with such a case. So he asks for advice from Adel, a “ more experienced” manager at the municipality. Adel tells Mourad that he has caught onto similar oversights in the past, and he advises that Mourad remedy the situation by adding the missing birth certificate to the central digital database.

Mourad then asks his colleagues, Amal and Monia, to register Meriem Ben Idriss’ birth certificate and then to translate it into French.

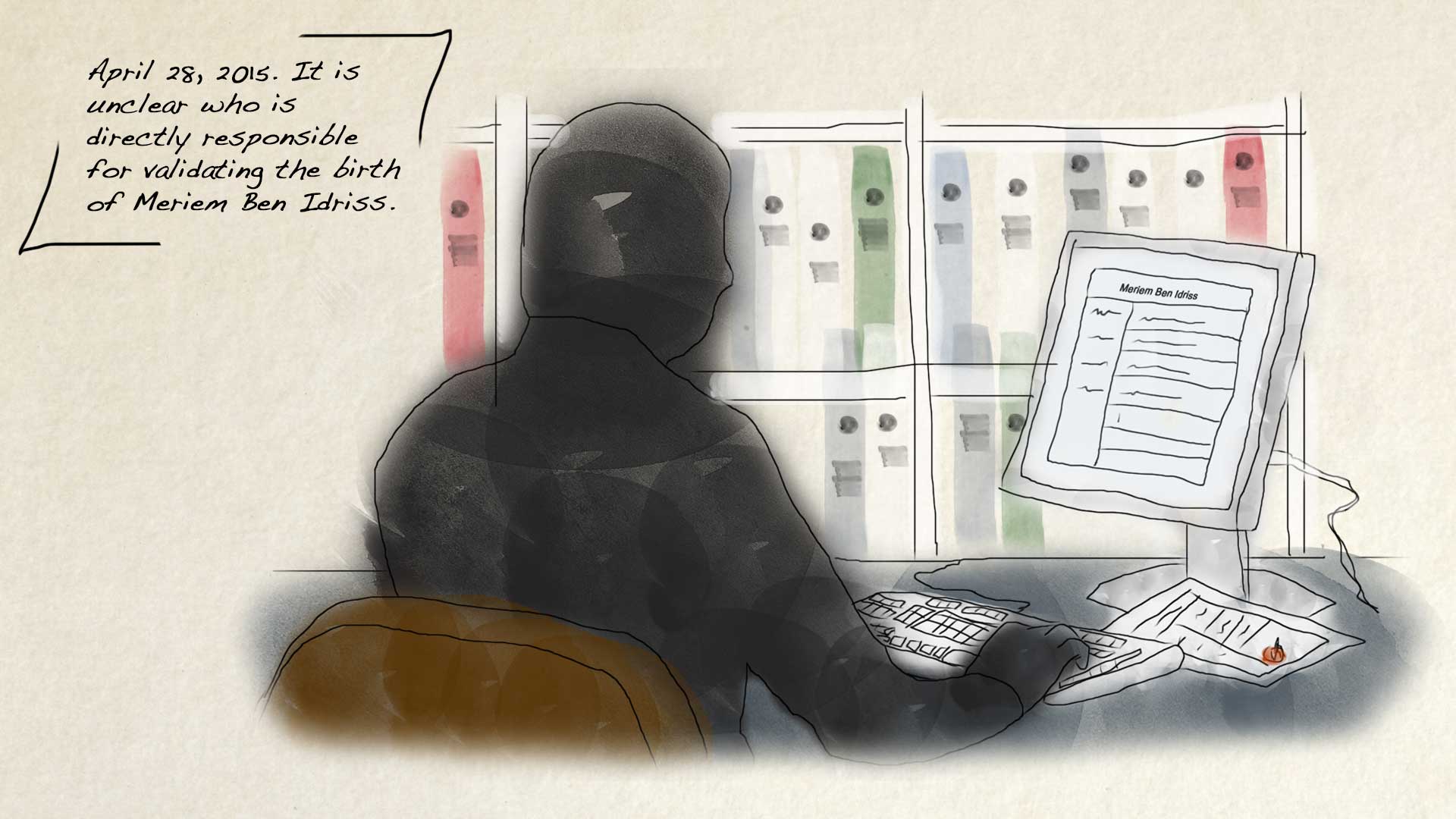

According to Adnene Saidane, head of IT at the municipality of Tunis Kasbah office, municipal employees cannot access or manipulate the central database related to civil status without logging in with their own unique password. Their passwords are meant to be confidential, and only employees from the IT department can access them. Once logged in to the database, employees can make changes to the database, but not without leaving a trace. All actions are linked to a name, date, and time.

The central database’s login records indicate that an employee at the municipality of Bab Souika registered Meriem Ben Idriss’ birth on April 28th, 2015. This employee, called Rym, was able to validate her own action and then produce two copies of Meriem’s new birth certificate within the database.

On the same day, a little after 13:00, “ outside of administrative working hours,” another employee named Boutheina translated the birth certificate into French and produced another four copies. Half an hour later, Monia makes an edit to the translated version and produces another copy. Another hour later, Rym prints four copies of the document in French.

As seen from the records, three people worked on registering and translating the “missing” birth certificate between 12:00 and 15:00. The records do not, however, indicate any involvement from Amal, who Mourad claimed was in charge of this task.

During his last meeting with Karim at the end of April 2015, Mourad gives him the newly registered birth certificate. Two weeks later, Mourad is arrested.

The system’s weaknesses

Mourad’s colleagues do not corroborate his version of the story. “ Out of fear of going down with him!” said one of his lawyers to Inkyfada.

“ I never had any knowledge of this story,” said Monia, one of the municipal employees whose login details were used to fabricate the birth certificate in the central database. Confronted by Mourad in March 2016, Monia, Boutheina and Rym maintained their innocence.

Boutheina says that she “ never added any names to the central database, or translated.” In any case, she would not have been in the municipality at 13:03, when her login was recorded, because it was her lunch break. Rym says she had been covering for a colleague in another position, so she could not have done these tasks either. And finally Monia: she affirms that they had all given their login details to Mourad starting in 2011 or 2012. Rym confirms this last statement.

Mourad maintains that he assigned this task to another employee, Amel, who used her colleagues’ login details because she did not yet have her own. But there is no trace of Amel, and still no one has asked to hear her version of the story.

Adel, the more “ experienced colleague,” does not help Mourad’s case. He would never have advised someone to add a birth certificate to the central system without respecting the formal procedure: submit a formal written request to the central administration, the only body authorized to undertake this action. He also claims that 20 years ago he thoroughly audited the registers, including those from 1986, from the Bab Souika municipality. Everything was copied into another register, including each document’s reference number. Of this he is sure: the birth no. 8920 in register no. 30 of the year 1986 did not exist in the records 20 years ago.

Two (un)identical forms

Another aspect of the official birth registration process works against Mourad: the matching copy of the birth registration form. Each time a birth is registered, two identical documents are updated; one remains with the municipality where the birth was registered, and the other remains in court.

Comparing these two documents, a discrepancy is revealed: Register no. 30 of 1986 housed in the municipality of Bab Souika includes one more birth — no. 8920 — than register no. 30 of 1986 housed in court. Mourad insists: it’s possible for births at the end of December to be recorded in the first register of the following year. But in register no. 1 of 1987, there is no Meriem Ben Idiss.

At this point during the investigation, a graphology expert is requested. The expert is asked to compare the handwriting from the two versions of birth registration no. 8920 against the handwriting on other registers from that time. They should have all been done by the same officer. The results of the analysis revealed that one of the signatures was falsified. Meriem Ben Idriss’ place in Tunisia’s civil records was subsequently “ frozen.”

A stillborn identity

In 2010 and 2011, the FBI carried out an operation called Ghost Stories, which targeted around a dozen Russian “illegals.” Some of these spies hide behind fake identities; others appropriate existing identities from the host country. Identities appropriated from host countries are more difficult to acquire, but they facilitate a deeper integration because of their legitimacy within public records. In any case, these “illegals” face greater risks because they are not part of a diplomatic corps and therefore cannot benefit from diplomatic immunity.

Mikhaïl Salikov and Kyamran Rasim Ogly Ragimov (who presents himself as Karim Brahim) were not “illegals” in Tunisia. They were diplomats who worked at the Russian Embassy.

During their missions in Tunisia, Mikhaïl and Karim established ties with at least four municipal employees. According to their confessions, the two Russian citizens obtained blank official documents, consulted (and even took into their possession) birth and death registers, and gained an insider’s understanding of civil administration procedures for Tunisians or foreigners residing in Tunisia.

In the municipality of Bizerte, Samia, head of civil registration, confesses to giving them access to all types of administrative documents, as well as to registers. This is likely how the Russians came to find a real identity for Meriem Ben Idriss’ father. Mourad ensures that he never granted access to these types of documents. But what he did provide was the birth certificate of a woman who never existed . . . even though her persona would only survive for a few weeks.

From June 2013, there is no longer any trace of Mikhaïl. This is when Karim picks up the baton. On May 16th, 2015, Samia arranges a meeting with Karim to retrieve two of her office’s registers from him. She has already been arrested; Karim is next.

During questioning, Karim confessed to having asked employees from four different municipalities for a number of important documents related to civil status. He also confirmed that he requested a birth certificate for Meriem Ben Idriss from Mourad. When asked why, Karim refused to respond. Part of the diplomatic corps, Karim is quickly released and extradited to Russia.

Mourad was not as lucky. In November 2017, he was sentenced to 15 years in prison. Samia and the two other civil servants were sentenced to 8. Mikhaïl and Karim will probably never be able to return to Tunisia . . . unless they find another “Meriem."