Between 2006 and 2015, Abdelli established links with three companies, one of which was created through a branch of HSBC Private Bank. In this same time frame, Samir Abdelli was politically active, and he eventually ran for president in Tunisia’s 2014 elections. Abdelli claims that these companies were formed for professional purposes.

In 2015, the Swiss Leaks investigation in Tunisia revealed that Abdelli had opened a bank account in 2006 with HSBC Private Bank in Switzerland. As the scandal was unfolding, Abdelli claimed to not remember the details of this account, despite its 80,000 USD balance. Regardless, he claimed, he was not in violation of Tunisia law (the Exchange Code) because he was not residing in Tunisia at the time. Later on, he claimed that the account was linked to his duties as a lawyer but didn’t comment on its connection to HSBC Private Bank. It was through this bank that Abdelli was connected to an offshore company, of which he became a shareholder.

Faygate Corp: Samir Abdelli’s Shares

Crédit : ICIJ

Faygate Corp. was a business registered in Panama in November 2006, with a capital of 10,000 USD divided between 100 shares. When these shares were bought, not even the company could access shareholder information; only the financial intermediary was privy to their identities.

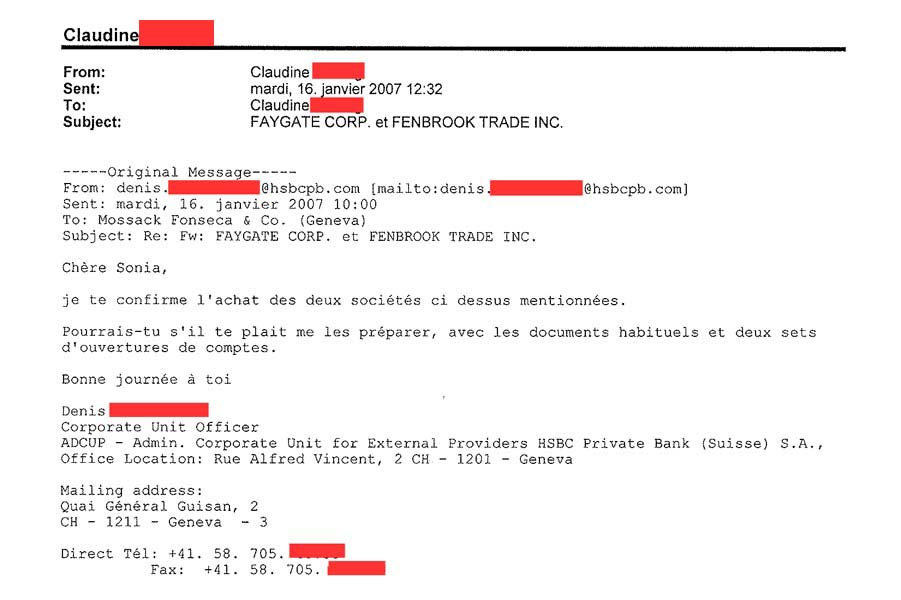

In early 2007, HSBC Private Bank contacted the law firm of Mossack Fonseca to inform them that a client intends to buy two companies, one of which was Faygate Corp. Abdelli quickly became a shareholder of Faygate Corp.

According to the documents analyzed by Inkyfada, Faygate Corp. closed its doors in October 2014, during the same period that Abdelli was running for the Tunisian presidency.

Online exchanges between HSBC and Mossack Fonseca regarding the creation of Faygate Corp.

Abdelli and his business partner, Tewfik Bendjedid

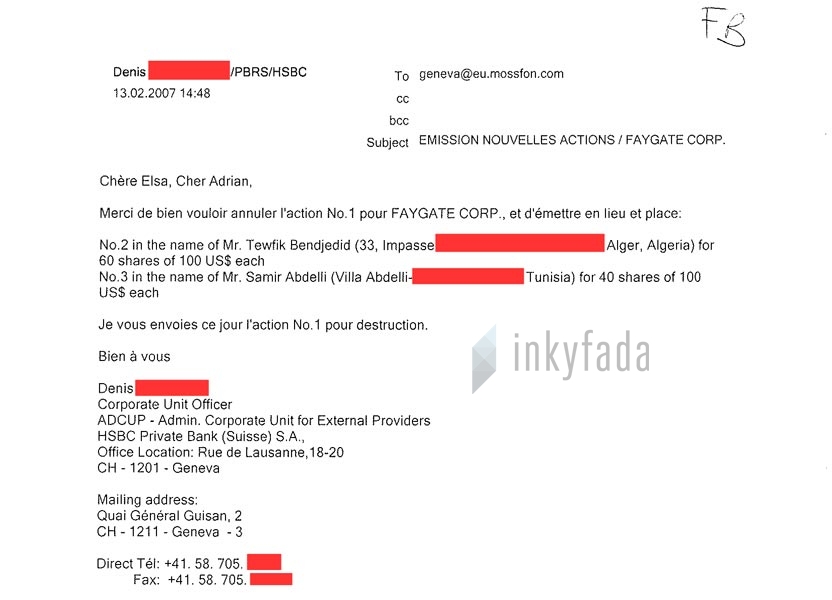

In February 2007, HSBC Private Bank contacted Mossack Fonseca once again, this time to request the issuance of two more share certificates. One of the certificates was issued in the name of Tewfik Bendjedid, residing in Algiers, granting him 60 shares. The other was issued in the name of Samir Abdelli, residing in Gammarth (a neighborhood in the suburbs of Tunis), granting him 40 shares.

Online exchanges between HSBC and Mossack Fonseca regarding the issuing of two share certificates in the names of Tewfik Benjedid and Samir Abdelli giving them 60% and 40%, respectively, of Faygate Corp’s shares

Tewfik Bendjedid is a prominent businessman with an infamous track record. He is also the son of Chadli Bendjedid, Algeria’s former head of state. Despite being linked to numerous scandals, the most famous of which involved embezzling millions of dollars from the Banque Extérieure Algérienne (BEA) in the 1980s and ‘90s, Tewfik Bendjedid has continued to pursue big business deals in Algeria and beyond. Bendjedid has a close working relationship with the Fechkeur brothers, who are a part of the Red Med group. This group provides services to the petroleum sector in the south of Algeria and owns a small aviation company, Red Star Aviation, which primarily transports petroleum companies’ personnel.

In an interview conducted by Inkyfada on March 29th, 2016, Samir Abdelli claimed to have been Tewfik Bendjedid’s lawyer. When Bendjedid’s nefarious reputation was brought up, Abdelli responded that “ those were old stories from more than 20 years ago.”

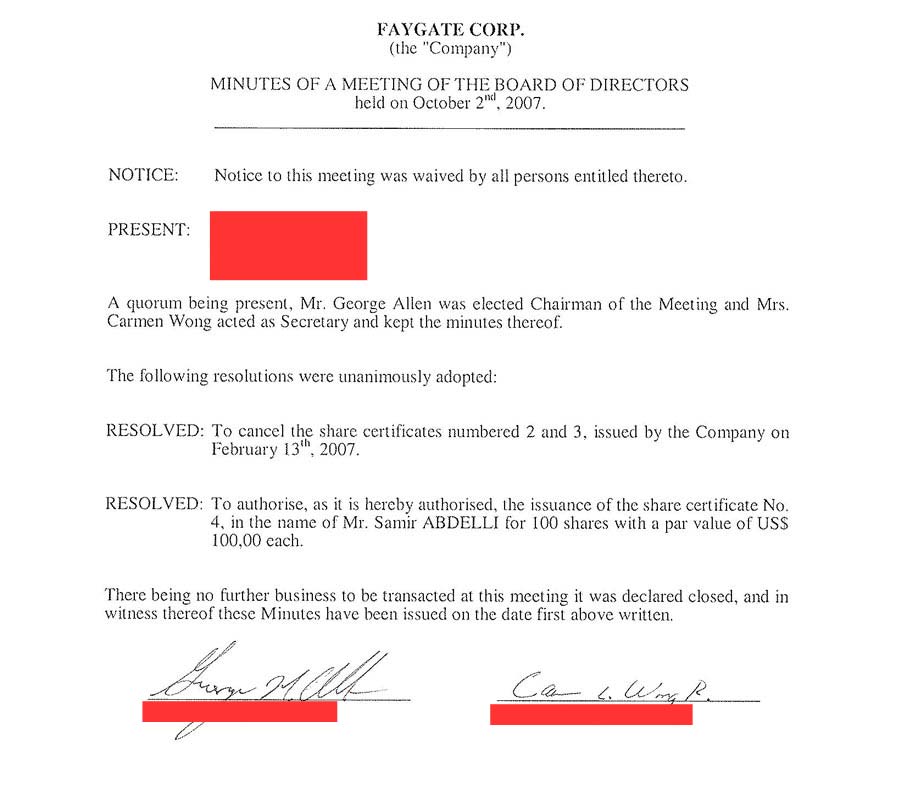

In October 2007, Abdelli and Bendjedid decided to no longer share Faygate Corp., so a fourth share certificate was issued granting Abdelli full ownership of the company. Thus, while working as a lawyer in Tunis’ Berges du Lac II district, Abdelli became the owner of a Panama-based company.

Meeting minutes in which Faygate Corp’s Board of Directors agrees to transfer all of the company’s shares to Samir Abdelli

Evading questions from Inkyfada’s team regarding the dealings of Faygate Corp., Abdelli maintained that the company served his professional activities and declined to provide further information. As he did during the Swiss Leaks investigations, Samir Abdelli claimed to have been living in Dubai at the time of the company’s incorporation.

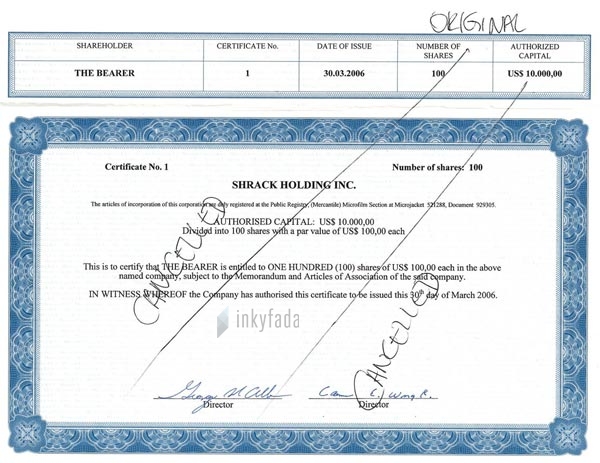

Shrack Holding: from ready-to-wear to haute-couture

The Panama Papers reveal another connection between Abdelli and offshore finance: a company by the name of Shrack Holding. Created in March 2006, Shrack Holding was a company just like Faygate Corp., off-the-shelf, registered in Panama, and with a capital of 10,000 USD distributed across 100 shares.

From his Tunis office in February 2014, Abdelli sent a fax to HSBC Private Bank requesting to transfer the administration of what he described as “my company.” He aimed to transfer the administration of Shrack Holding to an employee of Bedrock, a private investment firm with offices in Monaco, London, and Geneva.

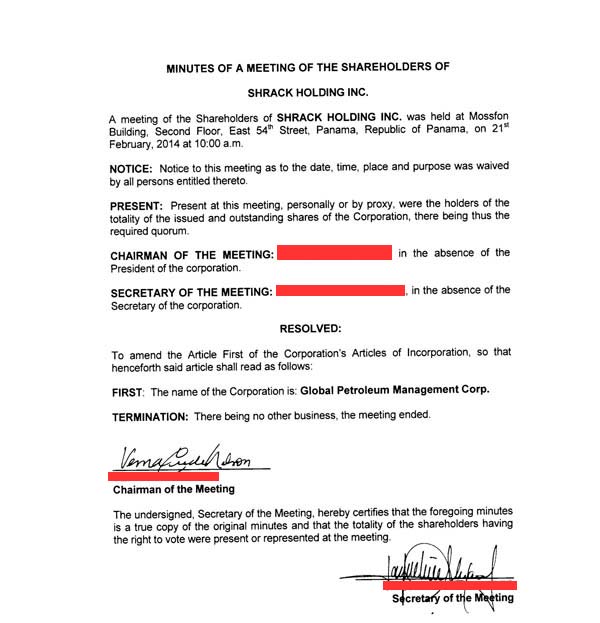

Soon after, HSBC sent an email to Mossack Fonseca informing them of the transfer of administration to a Mr T. from Bedrock’s Monaco branch. On February 7th, a Mossack Fonseca representative wrote to Mr. T to confirm the change of management. Then, one week later, Mr T. sent an urgent request to change the company name from Shrack Holding to Global Petroleum Management Corp. This information is revealed in the minutes of a meeting held between Shrack Holding’s shareholders.

Meeting minutes in which Shrack Holding’s Board of Directors agrees to change the company name to Global Petroleum Management

Global Petroleum Management: Meandering through financial arrangements

Documents show that once Shrack Holding was renamed to Global Petroleum Management, Samir Abdelli began to serve as the company’s lawyer.

This is where the financial arrangements become complex. On April 11th, 2014, barely two months after the name change, all of the company’s shares were transferred to the Metropole Palace Foundation. Foundations established in Panama enjoy special protections and offer an alternative way to create shell entities.

Share certificate giving 100% of Global Petroleum Management’s shares to Metropole Palace Foundation

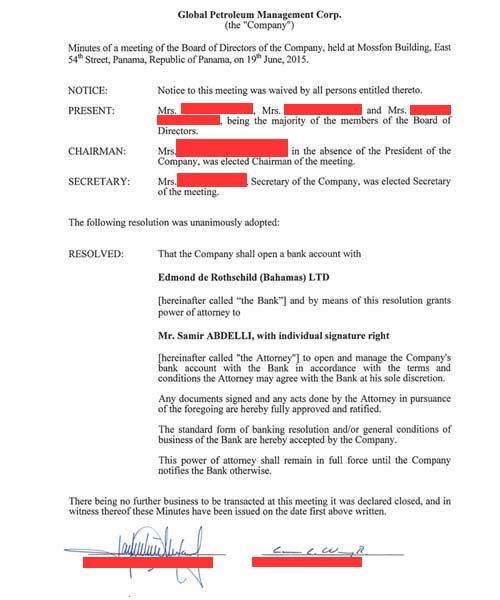

In June 2015, an employee from Bedrock Group Monaco sent an email to Mossack Fonseca requesting an agreement “authorizing the client (Mr. Samir Abdelli) to open a bank account” with the Edmond de Rothschild Bank LTD in the Bahamas and to provide him with signing privileges.. Abdelli was thus granted power of attorney, authorizing him to act on behalf of the company and to manage the bank account “ until he is notified of a change by the bank.”

Power of Attorney for Samir Abdelli to open and manage a bank account with Edmond de Rothschild (Bahamas) LTD

Global Petroleum Management and Tunisian Oil

In March 2014, Global Petroleum Management assigned Mr T. as the legal representative in negotiations with CRESCENT Petroleum Company International Limited, an Emirati petroleum company, concerning the Zarat oil field in Tunisia.

This oil field belonged to the state-owned petroleum company, ETAP, which, for more than 20 years, had exclusively granted exploration permits to PA Resources, an international petroleum group working primarily in North Africa.

On April 3rd, 2014, the Constituent Assembly attempted to suspend the renewal of exploration permits. The deputies referenced a report issued by the Court of Auditors that revealed several abnormalities in the extensions that were previously issued to PA Resources. In the end, PA Resources managed to secure another development plan with ETAP to continue working in the Zarat oil field. The nature of the negotiations between Global Petroleum Management and CRESCENT Petroleum Company is not known.

The business lawyer – interviewed

During our interview, Samir Abdelli put on a charming front. As he did in questioning related to the Swiss Leaks investigation, Abdelli welcomed us, listened, provided vague responses, wrung his hands, pretended not to remember many details, smiled nervously, waited for the interviewer to tire, and then ended the meeting, promising to do some reflection.

During a second exchange, Abdelli stands by his forgetfulness and minimizes the investigation: nothing is serious; everything is legal. In an email addressed to Inkyfada, he responded to some questions.

" Lawyers practicing in Tunisia or elsewhere . . . and who act in the name and on behalf of their clients and/or foreign colleagues, are legally entitled to act as such and in particular to represent and assist clients around the world in the context of their real, legal activities and for which they are legally mandated."

He insisted once again that he could not recall many details, even though some of the business activities in question were recent. And again, he assured that all of his companies were related to his work as a lawyer.

“ I am obliged to manage some legal aspects of my clients’ activities.”

He explained that in serving his clients, he could contact a colleague in another country “ to create one or more companies. I thus contacted specialized firms who would be able to take care of the creation of a company, its headquarters, the managers, who would be the lawyers themselves or notaries, until the opening of a bank account.”

Abdelli’s justifications for opening up offshore companies for professional reasons are precarious, especially considering his involvement as a shareholder in one that is now dissolved.

But he puts forth another line of defense:

“ It wasn’t a question of tax evasion or of money laundering. What interested me was the ease and speed (the same day) with which I could create a company and obtain the official documents (business registration, headquarters, the board of directors, and bank accounts). For our customers, it’s a big business argument.”

The lawyer and former presidential candidate never once acknowledged the darker side of this business argument, precisely regarding the opacity that shields these arrangements between asset holders and the movement of their funds. But we know all too well: tax evasion and money laundering thrive under these same conditions.