Vendors line the street stretching from Barcelona Square to El Kherba Square, showcasing an array of products along the roadside. Some items are displayed directly on the sidewalk using a simple plastic tarp known as a "Bache". Others are presented on sturdy cardboard boxes called "Kardhouna", while a selection is exhibited on wooden carts known as "Barwita".

Amidst this bustling scene, the voices of vendors fill the air, competing and harmonizing as they chant alluring prices. Meanwhile, some engage in explanations, negotiations, scolding, disapproval, and occasional shouts directed at passersby or fellow vendors. It's a convergence of diverse worlds coming together in a single place.

A melange of fragrances wafts through the air, encompassing perfumes, cosmetics, medicinal herbs, and less pleasant odors emanating from the entrances of the surrounding buildings. Suddenly, a flurry of activity breaks out, signaling a state of alert or emergency.

What draws these vendors to this particular street? Why did they select this location over others? What factors motivated them to gather here? Moreover, is their setup truly "informal" as labeled by official discourse, or does it entail complexities beyond such classification?

Based on the study published in October 2022 by the Tunisian Forum for Social and Economic Rights titled "The Spain Street market or the essence of a street economy in Tunisia", inkyfada embarks on a captivating journey. Through a combination of images, drawings, and interactive data, the aim is to delve into the intricacies of Spain Street, uncovering the vibrant world that extends far beyond the merchandise and the routes traversed by the vendors.

Spatial Distribution

Every day, vendors assemble along the street, commencing from the junction of Spain Street and Barcelona Square, stretching all the way to the crossroads of Commission Street and Sidi Bou Mendil Street on the opposing end.

Vendors can be found at the intersections connecting Spain Street with adjacent streets, predominantly comprising newcomers to the market who are yet to secure space within the main thoroughfare for showcasing their merchandise.

According to the study, the Spain Street market encompasses a range of 300 to 330 vendors. The research sample represents one-third of these vendors, with 48% utilizing "Bache" (tarps), 29% employing "Barwita" (wooden carts), and 16% opting for "Kardhouna" (cardboard boxes) as their means of display.

Vendors organize Spain Street based on three key criteria. First, the street is geographically divided into three distinct areas, each associated with a well-known location or building. The second division is determined by the perceived level of "threat" posed by the municipal police. During intensified police raids, vendors often seek refuge in Sidi Bou Mendil Street or the adjacent streets. The third criterion divides Spain Street according to customer traffic and movement, making it responsive to sales opportunities.

The vendor’s profile

In both reality and the perception of market-goers, Spain Street vendors embody a distinctive and stereotypical image. Natural elements have left visible marks on their appearance, such as darkened skin from prolonged sun exposure. Their attire bears signs of their trade, with dust and sweat clinging to their clothes. Many vendors opt for "Chleka" (flip-flops) as footwear, despite it not being the most practical choice for evading municipal police raids. Their clothing lacks coordination, often consisting of either the items they sell or secondhand garments. Most vendors have shaved heads and bear visible traces of dirt.

However, beyond these stereotypical physical attributes, the life trajectories of street vendors reveal a multitude of shared characteristics. While the research indicates that 80% of them hail from the city of Sbiba, specifically belonging to the "Ghlayguia" clan, this does not imply a homogenous group. Instead, what unites them are the shared experiences shaped by economic, social, and political conditions, influencing their perceptions of self, the State, and society. In other words, their worldview is shaped by the impact of these factors on their lives.

On the bustling streets, the economic and cultural characteristics of vendors emerge, diverging from the conventional traits of traditional economic actors. The study reveals that Spain Street vendors embody a "paranoid self," harboring doubts about others' intentions and lacking trust. This skepticism stems from a history of instability, disappointments, and frustration, linked to their educational abandonment during adolescence and detachment from their hometown ("Bled"), resulting in a sense of distance from their family. Emotional frustrations are also apparent, with many respondents recounting failed romantic relationships during their teenage years. Additionally, the vendors face economic frustration and experience symbolic and material violence in their interactions with both the street environment and the State. These adversities impede their ability to establish trust-based relationships and cultivate social capital beyond the limited networks of family, work friendships, and camaraderie forged on Spain Street.

Spain Street between Past and Present

Today, Spain Street holds a prominent position within the capital, situated in close proximity to Habib Bourguiba Avenue and Barcelona Square. It is also in the vicinity of notable landmarks such as Boumendil Market (Sidi Boumendil Street), Commission Street, and the central market.

The origins of Spain Street trace back to the initial core of the European city, established between 1835 and 1881. The formation of the Tunis municipality by Mohamed Bey on August 30, 1858, prompted the development of neighborhoods beyond the walls of the Medina. Among these was the commercial district, El Jazira Square-Sadikia, where Spain Street took root. Over time, the urban and architectural aspects of the city have witnessed continuous growth, evolution, and organization.

Slide the arrow to the left or right to view both images:

Spain Street derived its name from the Spanish embassy, which was established there since its inception. Similarly, adjacent streets housed embassies of other countries. The street was primarily known for its commercial function, particularly in wholesale trade. It served as a bustling marketplace for various food products, including fruits and vegetables, as well as items associated with Fondouk El Ghala, the wholesale market at the time, and the present-day central market. During that period, the neighborhood predominantly consisted of Italian residents, reflected in the Italian architectural design of the buildings, which typically comprised no more than two stories.

The avenue boasts a vibrant economic activity driven by the presence of vendors and merchants lining both sides of the street. Its strategic intersection with Barcelona Square attracts a steady flow of daily passersby, such as employees, workers, students, and pupils.

Over time, the economic landscape of Spain Street has evolved, particularly in the post-independence era when European embassies gradually relocated, paving the way for predominantly commercial activities. This transformation has been particularly pronounced in recent decades, with wholesale stores giving way to ready-to-wear and cosmetic shops, alongside the presence of informal vendors occupying the sidewalks.

Spain Street has emerged as a noteworthy example, even considered a "model street" for parallel, informal, and unregulated trade. Its liveliness and vibrancy have magnetized informal vendors to gather there.

Nowadays, Spain Street offers a variety of seasonal products, clothing, household goods, and merchandise related to religious events and holidays. These products generally come at lower prices or lower quality compared to their counterparts in larger shopping malls or stores. They often bypass Tunisian customs channels, as they are frequently smuggled in from Algeria, having been previously smuggled from Libya before 2011.

The emergence of street trade in the capital's sidewalks dates back to the 1990s. This coincided with an influx of men from the central-western regions of Tunisia, seeking to escape poverty and secure livelihoods. Turning to parallel trade, they aspired for social mobility that had been denied to them by the State and its official institutions.

The "Jlema" (people from the region of Jilma, Sidi Bouzid) were among the first to venture into this trade, particularly in the area between Commission Street and the "Sidi Boumendil" market. Their name became historically associated with this trade. With time, this group gained social status and acquired various skills. Eventually, they transitioned to running permanent and regulated stores in the Sidi Boumendil or Moncef Bey markets, moving away from informal sidewalk sales.

Generations have succeeded one another, and the number of street vendors from the Ghlayguia tribe in Sbiba surpassed those from the city of Jilma. This is significant as they belong to prominent tribes from neighboring towns of Sbiba and Jilma, which emphasizes the importance of primary tribal ties as a symbolic factor.

Interactions within Spain Street are structured based on clan affiliations, dividing the space among the vendors. Those not aligned with the dominant Ghlayguia clan, such as the Jlass, Ouled Ayar, or Jnadeba (people from Jandouba) clans, are required to pay a rental fee known as the "Maks." Failure to pay this fee can result in the seizure of merchandise and expulsion from the area. Seniority in the market also holds great significance, with the first arrivals reserving specific places that bear their names. Over time, they may trade, sell, or rent these spaces as if they were rightful owners.

"We are a family here, bound by blood and trade"

"A vendor, regardless of the tools they use for their trade such as carts, reinforced cardboard boxes ('Kardhouna'), plastic tarps ('Bache'), or rolling hangers ('Chtar'), indeed claim ownership over the space where they place their tools and merchandise from around 6 a.m. until about 6 p.m., without any formal contracts."

The vendors found along Spain Street are part of the same tribal organizational unit: the Ghlayguia of the Ouled Khelfa sub-tribe, belonging to the Majer tribe originally from the Sbiba region in the Governorate of Kasserine.

The findings from the field research indicate that the vendors collectively assert their physical ownership of the street, not just symbolically or virtually, although this ownership is not formally established through contracts. They have acquired this ownership by adhering to the principles of the early tribal approach of "conquest, possession, and long-term management." In other words, they have demonstrated their ability to control the street, not only in relation to the State but also in competition with non-clan members. This ownership is passed down from the first generation to the current second generation, and may potentially continue to the third generation in the coming decades.

Land ownership for tribes in Tunisia remains a collective ownership, serving as the material foundation for the reproduction of manpower and ensuring the conditions for survival. However, this ownership is constantly under threat and requires defense. The establishment of ownership relies on factors such as customs, traditions, possession, long-term management, and the military strength of the tribe, regardless of how the land was initially acquired and the boundaries remaining ambiguous. These conditions are crucial for proving ownership and maintaining its stability.

Spain Street, from its intersection with El Jazira Avenue to its intersection with Holland Street, symbolically intersects with the Sbiba delegation, despite being located hundreds of kilometers away. While officially documented as state property, it is under the authority of the Ghlayguia clan.

Belonging to the Ghlayguia clan entails affiliation with a tribe that has dedicated itself to commercial activities from the border to the street, generation after generation. They hold a monopoly over this activity, mobilizing their manpower, consisting of cousins and blood relatives. This creates a mechanical solidarity that safeguards individuals and the community, compensating for the absence of the State.

The study explains that the stagnation in rural areas' economic and social transformations, coupled with failed development projects, has led to a preservation of traditional determinants and limited social construction foundations within local communities. Social and regional marginalization has further reinforced insular relationships between groups and regions, resulting in weak national integration. As a result, tribal consciousness emerges through the control of the street, transforming it into a market monopolized by clan members, fueled by "Asabiyyah" (tribal solidarity).

The Ghlayguia clan, belonging to the Ouled Khelfa sub-tribe, has retained this "Asabiyyah" despite the exodus of its members to the city. The study refers to Ibn Khaldoun, who views "Asabiyyah" as a natural human inclination arising from kinship and proximity. According to Ibn Khaldoun, this inclination dissipates and disappears when kinship becomes unfamiliar. However, in the context of Bedouin urbanism, kinship remains intact and distinct, as the harshness of desert life forces tribes to live in isolation. Thus, only the poorest maintain clear kinship ties, as economic and social improvement, as well as the transition from rural to urban life, often erode such ties.

In contrast, the Ghlayguia of Sbiba perceive their migration to the city as a journey undertaken to sell goods supplied by their parent tribe, the Majer tribe. They consider themselves a commercial convoy representing a tribe settled in the capital, with the intention to return to their place of origin, Sbiba or the "Bled", once their mission in Spain Street is accomplished. Their migration is temporary, characterized by precarious professional, economic, and social conditions. They migrated not as individuals but in groups, and their mental and cultural identity remains closely tied to their tribal roots. Living in self-contained groups, they remain isolated from the wider society, with their primary purpose for moving to the city being trade. Eventually, they envision a permanent return to their homeland, Sbiba, or the "Bled" as they call it.

The exodus of Spain Street vendors, therefore, is a temporary one. Unlike the forced displacement experienced during the Bey era, the geographical division resulting from colonialism, or the disbandment under the pressure of the independent State and the impoverishment brought about by the Republic in search of employment, the vendors draw upon their history of itinerant trade caravans. They travel with their goods, contributing to the border and street economy in a historical continuity that is unparalleled in contemporary societies.

This phenomenon has its own historical and geo-demographic aspects. While the government considers this activity illegal, the human communities residing in the western border regions perceive it as a "normal commercial activity". This perception is deeply rooted in their cultural representations, which view freedom of movement and border crossing as vital and natural practices.

The border and street economy is an extension of an economy that would have been historically legitimate if it weren't for the actions of the Beys, colonization, and the independent State.

The territory of the Majer tribe, stretching across central and central-western Tunisia and central-eastern Algeria, has played a crucial role in the emergence of border trade, regardless of the type of merchandise involved. However, the mindset of the central tribes does not recognize the boundaries that separate these regions. The demographic characteristics of the region are marked by a tribal structure based on kinship ties and a perception of an open and unrestricted space for the movement of individuals. The concept of borders and barriers between the two states or areas is absent in this tribal mentality and perception. Consequently, the idea of freedom becomes a defining characteristic of the tribe, as predominantly nomadic tribes view themselves as free and quasi-independent entities.

Throughout history, the Majer tribe (from which the Ouled Khelfa sub-tribe is derived) has consistently opposed central power (the Makhzen). This opposition explains the lack of political support for the tribe in general and the Ouled Khelfa sub-tribe, in particular, regarding their economic activities. Despite numerous attempts at change, the State has been unsuccessful in abolishing the tribal structure and dismantling it at all levels. This resistance stems from these groups' rejection of the very notion of the State, and the possibility that such resistance could lead to a form of cautious coexistence between two entities that deny each other.

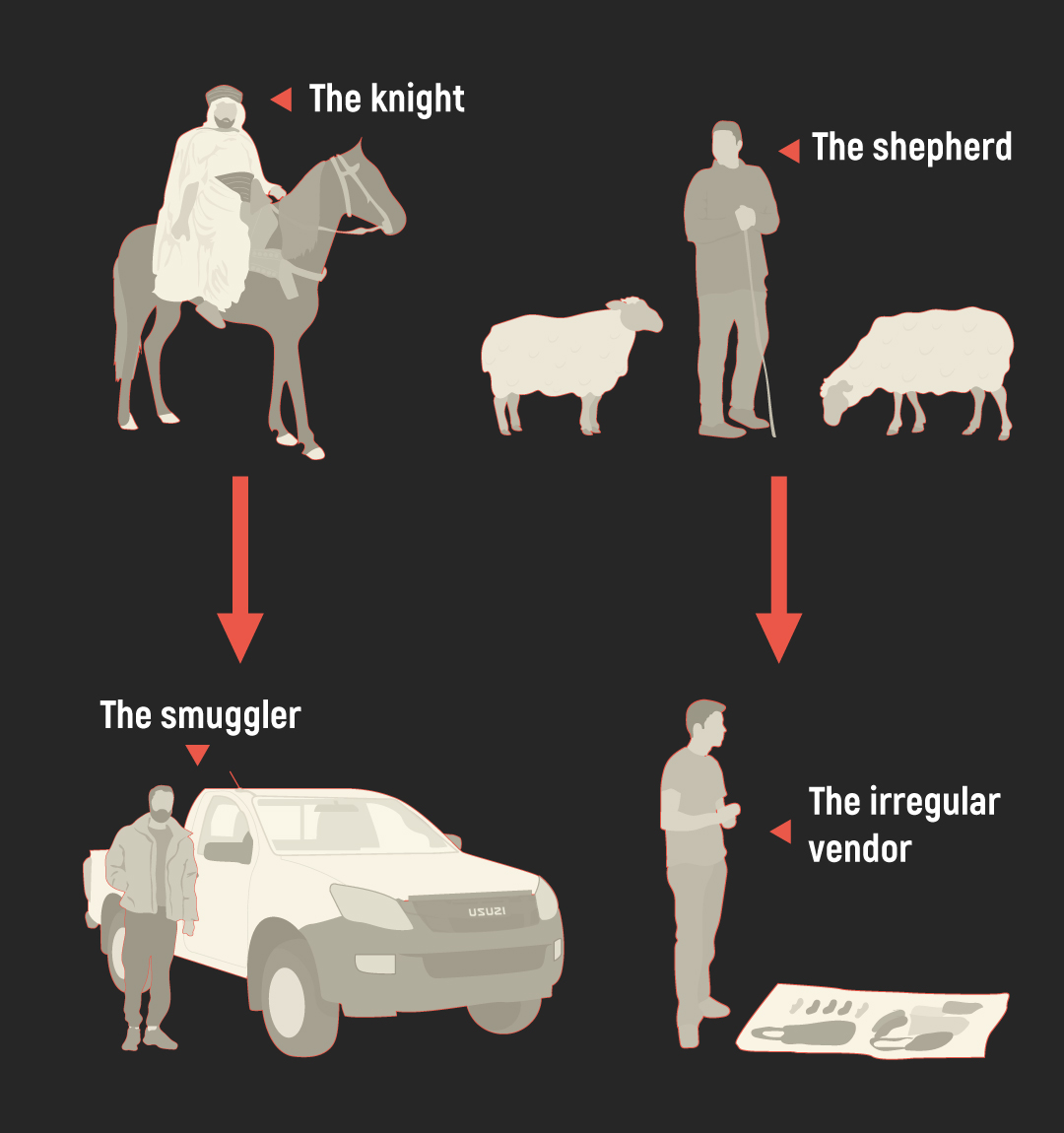

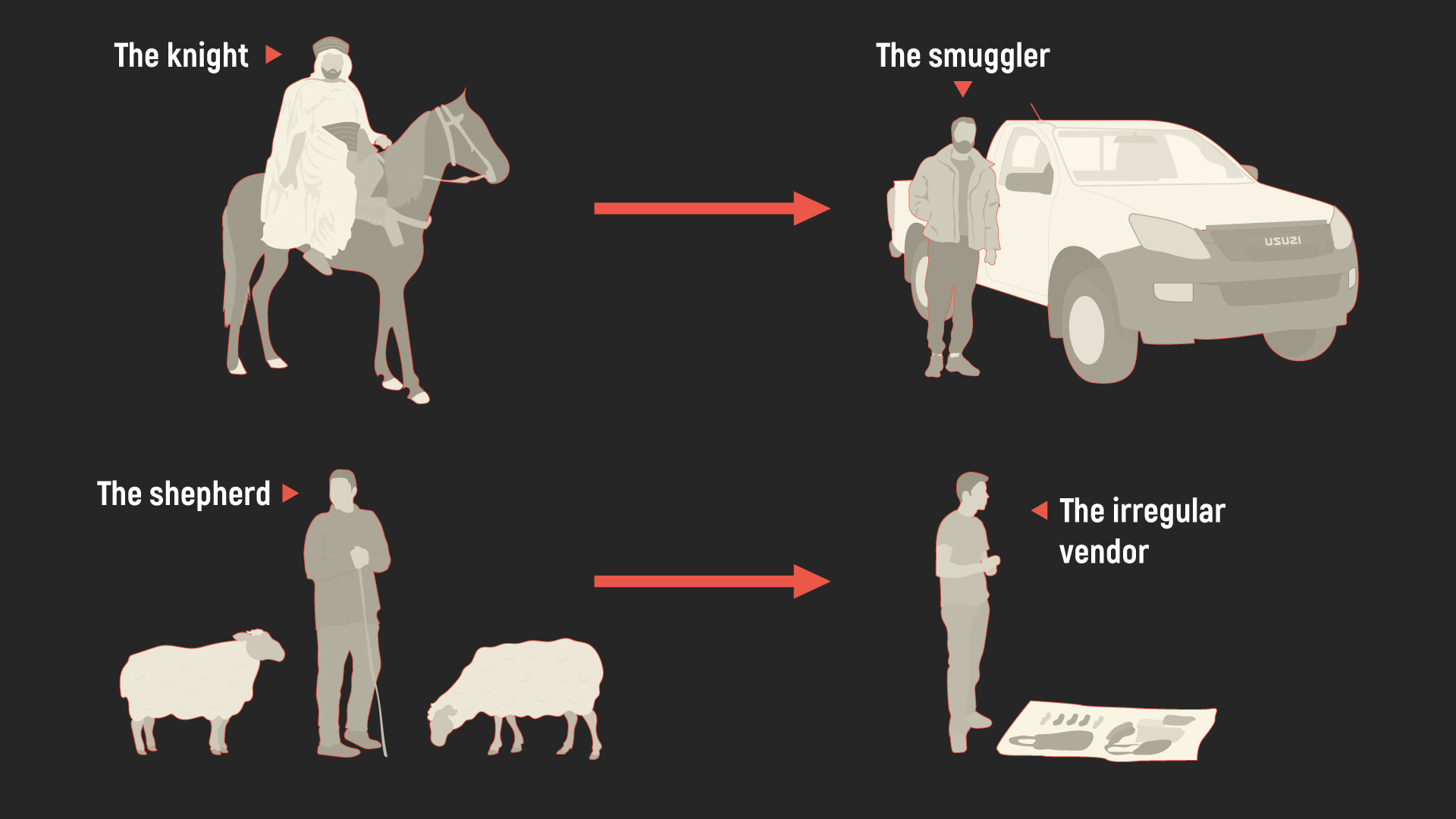

The Knight and the Shepherd vs.

the Smuggler and the Street Vendor

The "Ouled Khelfa" sub-tribe holds a distinct position as a commercial tribal unit within the larger Majer tribe, specializing in the trade of essential consumer goods. This sets them apart from other clans within the tribe, which historically engaged in activities such as agriculture, herding, religious management of "Zawiyas"* or organizing "Zerdas"**, and defense functions.

Within the vendor community, there exists economic and social democracy, as well as equality in terms of land distribution as a means of production. This is evident in the collective ownership of Spain Street, where land spaces have been democratically allocated among tribe members and the region. However, despite this equality, social disparities and differentiation exist within the tribe based on individual roles and functions. There is a dynamic interplay between tribal and clan solidarity on one hand, and class divisions and contradictions on the other, within a work group perceived as homogeneous by external observers.

The status of being an informal vendor or an informal border supplier largely depends on one's social standing, specifically their family's position and its symbolic and material capital: whether it produces knights or workers.

The cross-border goods smuggler, also known as "knatri", transports tens or hundreds of thousands of dinars worth of goods across the border daily in off-road trucks, risking their life due to potential gunfire, traffic accidents, or arrest by border patrols. This is different from the street vendor who sells goods worth hundreds of dinars on Spain Street every day.

The "knatri" represents the historical extension of the knight in the tribe, whose family had the means to provide a horse, saddle, and weapon (equivalent to a Toyota or D-max pickup truck today) to monopolize the honor of protecting the tribe and reap the associated benefits. In other words, they accumulated symbolic capital that generates or sustains material capital, thereby ensuring the tribe's survival.

In order to purchase a car and drive it across the border, one needed to belong to specific families within the clan that had connections with the border security forces (National Guard and Customs) on the Tunisian side. Equally important was the need to have connections with neighboring tribal units on the Algerian side, which were interconnected or affiliated with a shared tribal origin. These connections allowed for the purchase of goods from them, as well as establishing relationships with the Algerian border security forces.

In our current time, context, and reality, not all young people within the clan can become knights or "knatriya." This is influenced by the strong family organizational structure within the tribe, which ultimately gives rise to two distinct classes. On one hand, there is a working class represented by the vendors on Spain Street, who sell the goods imported across the Algerian borders by the wealthy class that owns the means of production and serves as the main suppliers.

From Sbiba to Spain Street

"We arrived here gradually and over time... When I first got here... I was ten years old... My relatives took me in."

The cultural capital and reproduction theory is evident among the vendors on Spain Street. On one hand, the educational background of parents and the cultural capital within the family play a role, while on the other hand, the economic and social vulnerability of both the family and the region as a whole further hinder the opportunities for children in education and beyond. These objective circumstances contribute to the perpetuation of poverty, the inheritance of social class, and engagement in demanding occupations, all of which can be measured sociologically.

Those who didn't have the fortune of being born into a "knatriya" (smugglers) family were inevitably bound to pursue street vending on Spain Street. Generations enter and exit this trade, to the extent that the newest arrival, at most 18 years old, learns the trade's skills and secrets from a cousin, seeking refuge in an unfamiliar big city upon arrival. Thus, they become apprentices in the art of buying and selling, taking a fellow tribe member as their mentor, who imparts the skills and expertise of the vendor community as part of an inclusive professional society.

Experienced traders with considerable wealth, symbolic capital, and strong social connections represent a minority within the group. They assume the role of mentors, offering protection and support to newcomers in exchange for their labor. Workers are selected based on family ties and their precarious social circumstances, often including children aged 12 to 16.

The recruitment process typically involves a phone call, establishing direct communication between the capital owners who possess multiple street vending locations.

These owners grant these stands to the vendors working under them, thereby increasing their own wealth and expanding their street vending fleet.

Spain Street vendors can generate profits that reach as high as 50% of their overall revenues. These profit margins vary depending on the goods being sold and the season. For instance, profits can exceed 300% for seasonal products like meat storage bags during Eid al-Adha, while toys, Eid clothes, and school supplies yield profit margins ranging between 100% and 150% during their respective seasons. It is important to note that vendors only pay for the goods after they are sold, as part of a transaction guided by the primary tribal ties between the aforementioned supplier and vendor classes.

The path of a street vendor is well-defined. It begins when a child leaves the Sbiba area to work as a "Sanaa" (apprentice) for a business owner, earning a daily wage of 60 dinars or sharing the revenues through a verbal agreement. After approximately five years of work, as reported by some vendors, the "Sanaa" may become a business owner capable of employing others within their geographical area. Alternatively, they may choose to operate individually as the owner of a street vending stand, selling specific products at a lower cost in terms of purchasing power. This approach minimizes the risk of significant loss in case of seizure by law enforcement officers.

"We are hostages of the State"

From the era of Beys to the present day, spanning the colonial period and the rule of the independent State, State policies have consistently marginalized and impoverished rural and inland regions in comparison to major cities, particularly the capital and the coastal areas. Throughout history, reactions to these policies have ranged from revolt to submission and compromise, varying depending on the context, regions, and tribes. Today, we are witnessing a new form of reaction: an entire informal economy operating through tribal dynamics.

It is both a clandestine and overt, informal and formal, unregulated and regulated economy.

On one hand, it functions as an informal economy, operating outside the bounds of formal regulation. It is also an unregulated economy, as it operates without adherence to recognized labor regulations. On the other hand, it can be considered formal because the state acknowledges its existence, albeit unable to eradicate it. This is not due to security constraints but rather due to its economic and social importance, which compensates for the state's absence. The informal economy operates through unrecognized contracts based on a sense of mechanical solidarity within the vendors' community, bound by primary connections.

The State's security efforts, including border patrols, customs, police, and municipal authorities, have failed to address this issue. The failure is evident not only at the borders, which have become porous, but also on the streets and avenues, which have transformed into bustling markets. These markets heavily rely on an informal economy that has gained prominence, surpassing the formal economy in various aspects and competing with it in several product categories that the latter is reluctant to introduce into the Tunisian market at competitive prices.

The State neither desires nor serves its interests to suppress an economy that provides an affordable marketplace for the majority of middle and lower-class consumers, while also offering direct and indirect employment to thousands of people. The ruling "system" is incapable of compensating for this economy and is unwilling to compromise social stability. Thus, for decades in Tunisia, the government has adopted a diverse and evolving policy, intervening as a major actor to balance the informal economy.

The "Ouled Khelfa" sub-tribe no longer seeks anything from the State, nor does it allow the State to assert its influence. It is a tribe that generates an entirely autonomous economy, beyond the control of the capital. This economy is not based on a fiscal relationship with the State, but rather on a symbiotic one, characterized by bribery "Jaala" of border patrols or customs agents in the event of a smuggling truck ambush, and at times, even without an ambush. They also offer bribes to municipal police officers in Spain Street (Achour/Khamous), or contribute to financing a political party's election campaign or supporting a candidate, as a means of ensuring peace, security, and protection.

"We are colleagues of Bouazizi"

In 2011, as trade union activities and demands were becoming increasingly democratized in various professional sectors, the "Union of Independent Traders" was established and became part of the Workers of Tunisia's Union (UTT), which was also created in the same year. This union had a central goal of regulating the profession of "independent merchants" to protect their income and improve their working conditions.

The term "independent traders" carries a "symbolic meaning" as it aims to remove the stigma associated with the street vendor label by proposing a new socially acceptable category. The Secretary-General of this union once expressed their vision by stating, "We are colleagues of Bouazizi". However, within the ranks of street vendors, things appear to be much more complicated, as the Union of Independent Traders has taken conflicting positions driven by economic interests and clan affiliation.

The union has advocated for the regulation of street vending in designated areas in exchange for a rental fee. For instance, the Carthage Avenue area, along with other locations in the capital such as Sidi El Bechir, El Kherba, Mongi Slim, and El Kallaline, can accommodate up to a thousand vendors. While the development of the Carthage Avenue space is still pending, the union has successfully secured other spaces.

The establishment of regulated vending spaces, like El Kherba and other designated areas, has brought stability to the incomes of many vendors and provided them with a sense of security. However, the process of determining the priority list for occupying these spaces appears to be in the hands of the union office members. Moreover, the criteria for inclusion on this list do not seem to be clear to everyone. This situation has resulted in doubts and even disputes among some Spain Street vendors regarding the legitimacy of the union.

But do these spaces truly meet the expectations of all street vendors? These demands already fulfill the needs of a portion of them: those who lack the financial means to sustain themselves in Spain Street and its surroundings. However, those who already dominate the field, particularly members of the largest and most influential clan on Spain Street, have little interest in the call for more developed spaces.

The former Governor of Tunis, Kamel Feki, who was recently appointed Minister of the Interior, stated in an interview with a private radio station last January that the Governorate is collaborating with the city's eight municipalities to develop an action plan for these markets. This plan entails the establishment of a "circular weekly market with a minimum of 400 vendors". These vendors will regularly set up in designated spaces determined by the municipalities on a rotational basis. He further explained that this system will require a "symbolic" contribution from vendors to cover market expenses, space rental, and social security. According to him, this represents a "radical solution" that can be implemented "within the next six months".

"Pending the finalization of in-depth discussions with the municipalities", the former Governor of Tunis suggests "curbing this phenomenon through increased police intervention", particularly concerning certain types of products such as second-hand clothes sold on sidewalks, which he deems "unacceptable".

Police intervention has become almost routine in the lives of street vendors, to the extent that clashes with law enforcement officers have become a daily occurrence, and evading them has become a necessity for the preservation of their livelihoods.

"Everyday State"

Like any other day, Hamma*, one of the vendors, stands in front of his cardboard box in his usual corner at the end of the street. From dawn till dusk, he enthusiastically promotes his modest merchandise, hoping to catch the attention of passersby.

Suddenly, a wave of panic sweeps through the street. Sirens blare and police cars rush onto the scene. The voices of police officers fill the air with harsh insults and profanity, creating a collective frenzy. In the midst of the chaos, the vendors' voices echo through the air, alerting one another.

"It's a major raid," one vendor informs his colleague, who quickly gathers the edges of the tarp covering his merchandise. He drags it along the ground while keeping a watchful eye for the police. With a sense of urgency, the vendor starts running, aware that this large-scale raid, accompanied by a municipality truck, aims not only to intimidate but also to seize their goods.

Within seconds, the bustling market transforms into a scene of general panic. Merchants abandon their stalls and rush towards Sidi Boumendil and the surrounding streets. However, Hamma makes a bold decision. Instead of fleeing, he courageously runs towards the rapidly approaching police, hoping to delay them and give his colleagues a crucial head start.

Hamma is a "chattar", a designated role he has taken on by settling at the end of the street. It is a collective strategy to confront the "everyday State", in other words, the police who represent the State's presence in the vendors' lives on a daily basis.

Fleeing is a spontaneous and common tactic employed by vendors to safeguard their daily earnings from seizure and to manage the inherent unpredictability and uncertainty that accompanies their trade.

Police raids represent moments when the State takes to the streets. Some vendors, particularly those with more experience, may sometimes foresee these raids. However, law enforcement officers generally avoid conducting raids in Spain Street during "peak" periods when there is a higher demand for the vendors' goods, such as during Eid el-Fitr, the start of the new school year, or other holidays that result in increased consumer activity surpassing the annual average.

Reverting to Tribal Era

200 years ago, the industrial revolution replaced the family and the community with the State and the market. But what about societies that haven't undergone an industrial revolution? Where the State and the market rely on other States and economies? Where there was no transition from feudalism to capitalism, but rather a neutralization of production relations resulting from prolonged colonization? In this context, the informal vendors of Spain Street represent, at least in part, evidence of the genealogy of Tunisia's historical backwardness , as explained by Hédi Timoumi, and its impact on our present economic and social reality.

The absence of a welfare State, the inability to establish a market economy capable of integrating the majority of citizens, and the marginalization of rural areas that compel people to migrate to cities in search of the State and the market—these are all factors that account for the presence of these vendors on Spain Street.

Our State, national economy, and market cannot accommodate everyone. This is a result of a process of structural reform that has been ongoing for several decades, influenced by a global and unequal division of labor that, instead of bringing about positive change, has exacerbated the situation. Our era could therefore be characterized as the era of the family or its resurgence, but it could also be the era of groups and collectives, or even tribes with their inherent social cohesion and solidarity, regardless of the evolving forms and configurations they take.

***

To learn more about the various aspects of the study, you can listen to the two episodes of the podcast series "Talking Papers" featuring Sofien Jaballah, the study's coordinator and editor, and Ridha Karem, researcher and author of the chapter on the "approach to the genesis of the masculinities of the street trader".