Some of the people standing around him came to pick up the packages and bags that their relatives sent to them from abroad. Others are hoping to get a space for their packages in the roughly 7 meters long and 2,6 meters high VW Crafter, so that Aymen can bring them to Austria and Hungary in the coming days.

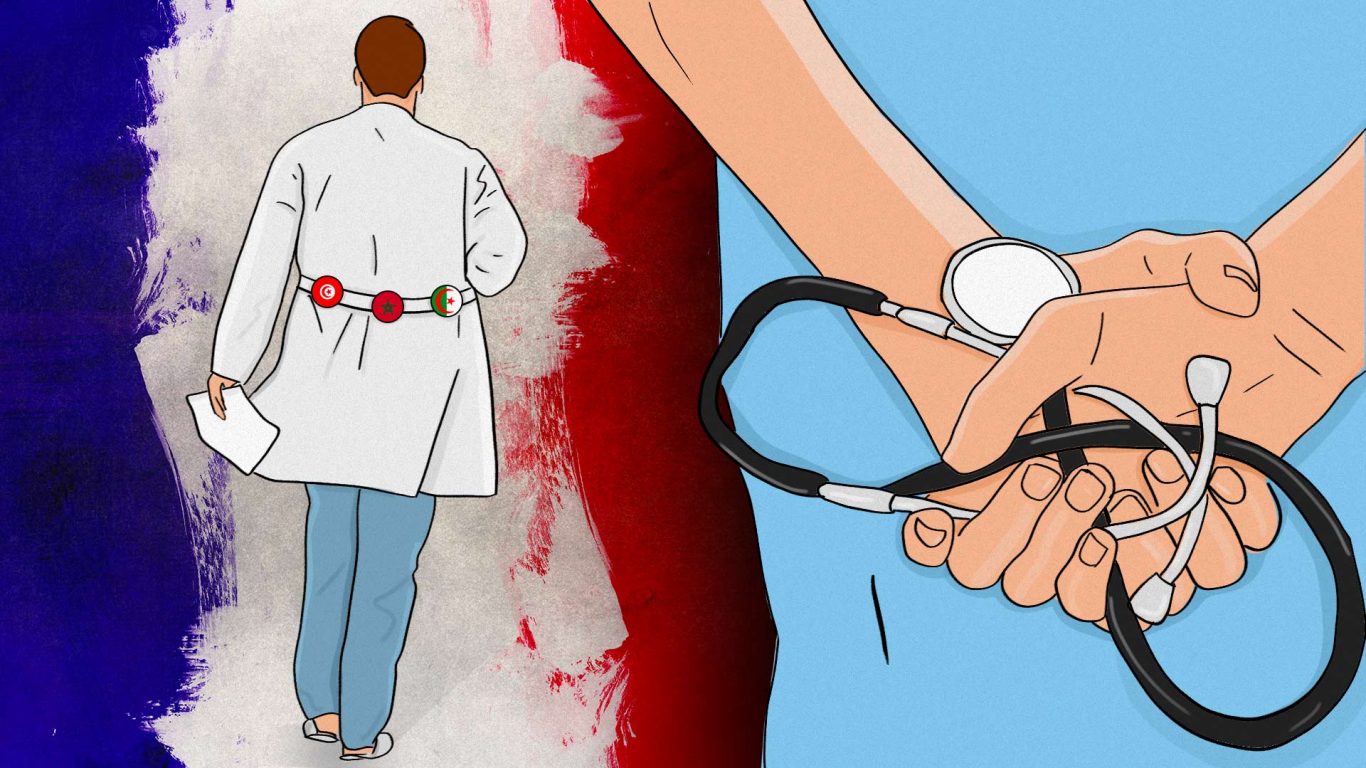

Aymen is one of the dozens of private transporters who are using their cargo vans to transport goods between Europe and Tunisia, relentlessly driving through different countries and crossing the mediterranean sea. He and his colleagues are creating a bridge between Tunisians who are living inside of Tunisia and their relatives living abroad. They are helping parents send Tunisian food to their children who are studying outside of the country and people in Tunisia to buy products that are not available or too expensive in Tunisia.

However, the vast majority of these transporters do not have a registered business. They are working illegally, moving goods across borders without having the permission to do so commercially. For the customers this means that they can never have a guarantee that their belongings will actually arrive at their destinations. And even for the transporters, the risks are high. Since most of them are working illegally, during every trip they take, they are at risk of getting detained at customs. Nonetheless, this business kept growing in recent years. Why? And how exactly does all this work?

On the same subject

A growing field

The business of transporters has existed for a long time already. Moncef*, who claims that he was one of the first transporters between Europe and Tunisia started doing this work 27 years ago. At that time, he and some people from his neighborhood used his cargo van to transport personal goods and other things like car parts from France to Tunisia and back.

With the years, Moncef became known and made himself a reputation in the Parisian region. He was driving seven to eight times per year from France to Tunisia and back and estimates that in total he had around 400 customers, all of which found out about his services through word of mouth.

According to Moncef, the business of private transporters has grown in the past three decades.

“At first, a couple of trucks came from Marseille, now there are 20 to 35 on every ferry”, he says.

While the first few transporters mainly operated between France and Tunisia, over time, more routes started to emerge. Today there are transporters working between Tunisia and countries like Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Hungary and the United Kingdom.

Social Media platforms like Facebook help transporters to reach more potential customers and to inform many people at once about their trips and services. On Facebook, one can get an idea of just how much the business of private transporters has grown in recent years.

While there are no official numbers about the amount of transporters who are working between Tunisia and Europe, inkyfada could identify more than 60 Facebook groups or Facebook pages offering this kind of service with a total of more than 280.000 members and followers.

Considering the fact that most of the transporters work illegally, it is remarkable how openly they share information about their work online. Despite the risks, some transporters like Aymen publish the meeting points and their itinerary on Facebook to inform their customers. Yet, many of them refused to talk to inkyfada’s journalists about their business.

A profitable business

The prices for sending packages and bags with private transporters are not fixed and can vary from transporter to transporter. In most cases, customers pay around three to five Euros (around 10 to 17 Dinar) per kilo. For electronic devices, they usually charge extra because of the additional custom fees.

The demand - and with it the prices - to send things from Tunisia to Europe is lower than from Europe to Tunisia. One former transporter tells inkyfada: “From Europe to Tunisia, people mostly send products that you can’t find in Tunisia in terms of their quality or price”. These include for example clothes, kitchen utensils, small electronic devices, cosmetics and even car parts. The other way, people usually send traditional food or products like olive oil, spices and dates.

According to his Facebook group, Aymen takes around one round trip from Europe to Tunisia and back per month. For each kilo that he transports, he charges 10 Dinars from Tunisia to Europe compared to five Euros from Europe to Tunisia. Considering the fact that his VW Crafter can load more than 1.300 kg of goods, he must be earning a considerable amount of money with his trips between the two continents.

Moncef estimates that with each one-way trip, a transporter makes around 2000 to 2500 Euros (around 6700 to 8400 Dinar) profit. However, he also stresses the fact that this number can vary a lot.

“If you don’t have a minimum of 200 to 250 clients, the trip can get expensive with the price of the boat ticket, gas for the van and the customs tax”, he says.

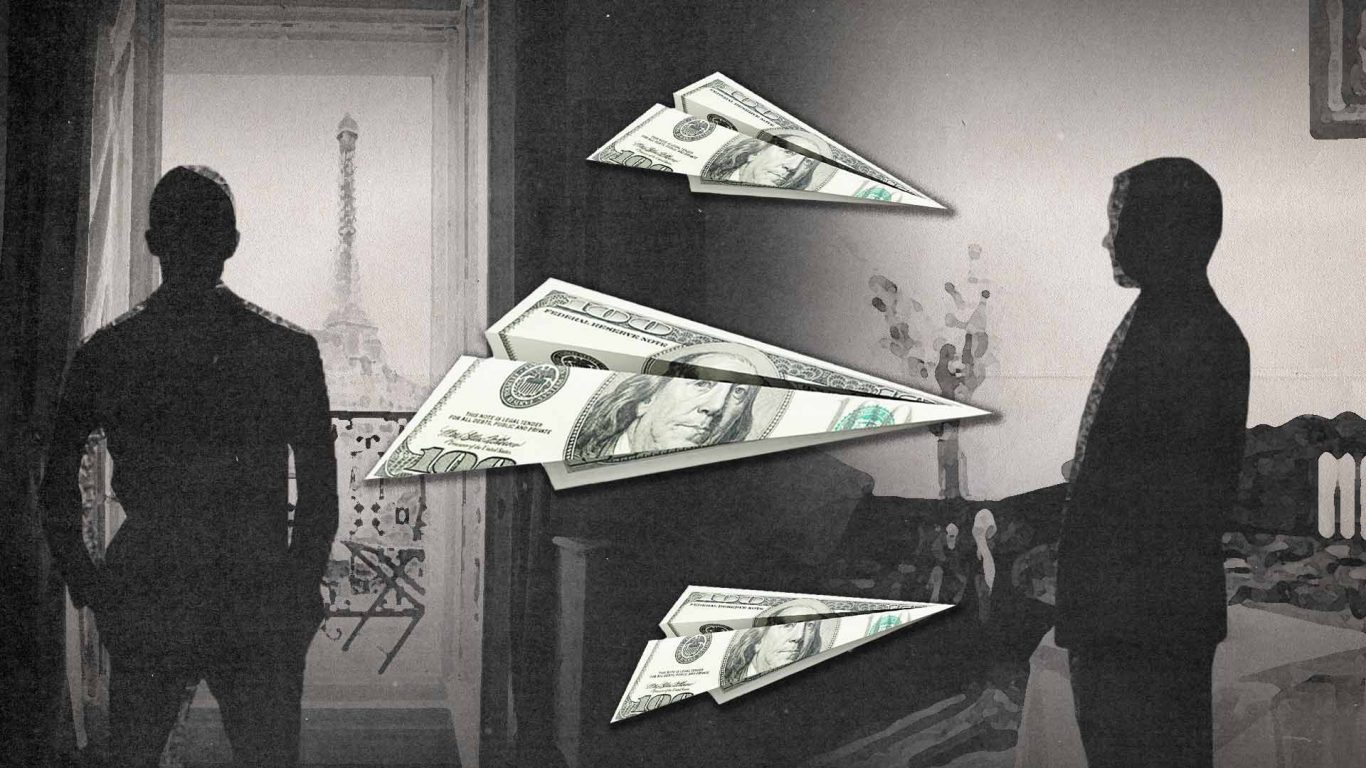

Besides transporting goods, some transporters also exchange money for customers who want to send money from Europe to Tunisia. That way, their customers can bypass high transaction fees and avoid issuing too many mandates, which can attract the authorities’ attention.

On the same subject

Apart from the transporters themselves, there are different other people who are profiting from this business. To deliver their packages inside of Tunisia, some transporters turn to local transport companies within the country. “They bring the packages from one city to another for you, charging around 10 Dinar per package regardless of its size or weight”, one former transporter tells inkyfada.

Hedi*, a Tunisian living in Paris who used to work as a transporter himself, now earns money as a “broker”. He puts clients in touch with transporters by finding them the best price and earliest departure. “They know me, they know I’m trustworthy so they ask for my help to find other trustworthy transporters”, he says.

There are also some women who are working as “pick-up stations” for various transporters at a time, Hedi tells inkyfada. These women store the packages at their apartments or houses until the clients pick them up. According to Hedi, they charge 0,500dt per kg and make around 1000 Dinar per month by handling roughly 500 kg of packages per week.

The better option?

Different customers tell inkyfada that they prefer to use private transporters instead of official post or transport companies because they are cheaper and less complicated to use. “If you send something through the regular post, you have to take a day off. You have to spend an entire day at the customs office and sometimes still don’t get to take your stuff out. Then you have to go the next day to finish the paperwork”, Ahmed*, who has been buying goods from overseas for more than 14 years and who prefers to use private transporters, tells inkyfada.

Ahmed describes himself as a “car enthusiast” and owns a number of cars, some of which are very old. Since the import and sale of car parts is tightly regulated in Tunisia, transporters are often the only way to obtain certain products for people like Ahmed. “The transporters are the only solution for us car guys to get parts or anything related with our automotive passion to Tunisia”, he says.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when international air traffic came to a halt, transporters were for many the only option to move things from Tunisia and Europe and back within a short period of time. Claudia, for example, who lives between Germany and Tunisia, needed to send medicaments to a friend in Tunisia during this time. “Because it was not possible to travel back and forth due to the flight cancellations and travel restrictions, we had to deliver her medication with a transporter”, she says and adds: “It couldn't be sent by post because it would have taken too long.”

For many, transporters provide a quick and easy way to send things back and forth between Tunisia and Europe. It's a solution to a problem that many Tunisians have, both inside and outside the country. However, this service also comes with certain risks…

“They collect the goods and the money, then they disappear”

For the customers, the fact that most transporters work illegally, means that in general their services are cheaper and easier to use than other official transport or postal companies. However it also means that they are more vulnerable to being scammed, since they don’t have any legal contract or proof for having handed over the goods and money to the transporters. According to Moncef, fraud and theft have increased in recent times.

“More and more transporters cheat their clients. They collect the goods and the money, then they disappear”, he says.

One of the people affected by this is Mohamed, who used to live in France. Before looking for a transporter that could help him bring furniture worth 10.000 Euros from Paris to his newly constructed apartment in Nabeul, he had used the service of private transporters before. It was small stuff that he had sent to his friends and family back home in Tunisia. Mohamed had found the transporters in Facebook groups and everything always arrived without a problem, he says.

But when he needed to send half a truck of new furniture, he wanted to be extra sure that his belongings would arrive without problems and in good condition. He asked an official moving company about the possibilities of shipping his furniture from France to Tunisia, but decided not to engage them after learning that he would have to reserve and pay for at least half a container, which would have cost him 2500 Euros (around 8400 Dinar). “So I called a friend and asked him if he knew a trustworthy transporter. He gave me a phone number, I called this guy and we met”, Mohamed recalls.

The transporter, Kais*, told Mohamed that he would transport his furniture for 1700 Euros, which is equal to nearly 5700 Dinar. He told Mohamed, that he doesn’t have to worry, that there would be no issues for him to bring Mohamed’s furniture to Tunisia because he has many connections in the customs there. Mohamed agreed and in November 2021 deposited his furniture in Gennevilliers, in the north of Paris, where Kais lived at that time.

After that, Kais disappeared for a while. Mohamed tried to reach him, but his calls didn’t get through. Several months later, Mohamed’s furniture still hadn’t arrived and he started suspecting that the transporter was just trying to gain time so that he could sell his belongings. Because of that, Mohamed went to the police station to file a complaint. The police officers already knew Kais, Mohamed says. According to them, he had been previously arrested for the falsification of ID cards and stealing rental cars.

It didn’t take long until Mohamed found other people who had also been scammed by Kais and his non-existent company. “I published a post on Facebook, warning people to be careful because this guy steals”, he says. “After that, many people contacted me and told me that they had the same issue and that the bags they sent with him never arrived”. Unfortunately, the police could not help Mohamed since he did not send his furniture with an official company.

“They told me there is no contract, there is nothing and that finally it is my fault”.

Mohamed is by far not the only person whose belongings did not arrive at their destination. On Facebook, one can find dozens of cases of people who got scammed by transporters and who are now trying to warn other people online.

Even when transporters are not stealing from their customers, there is still always the risk of goods being seized or damaged during the customs control. Because of this, when using an illegal transporter, customers can never be sure if their belongings will arrive at their destination, no matter how trustworthy the transporter might seem and how many people recommend him.

At customs, "if you don't pay, they will have no mercy"

For the transporters who are not registered, one of the riskiest parts of their work is getting through customs control in the port of La Goulette, where the transporters arrive after taking the ferry from France or Italy. In order to do his job legally, a transporter should be accredited under the “TIR Customs Convention for the international transport of goods”, a lawyer tells inkyfada, which most transporters are not.

According to Salma Kalamoun, Press Officer at the Tunisian customs office, if a private transporter arrives at the customs control in La Goulette, the process should run as follows: The transporter has to hand a list of all the items he is carrying to the customs officers who will then compare the list with what the transporter is actually carrying. After that, a taxation will be applied, depending on the nature of the goods. In addition to that, according to Salma Kalamoun, there are several cases where the goods would be seized. One of these cases would be if the goods have a “commercial appearance”.

However, despite these regulations, it is clear that carriers are passing through customs regardless of the “commercial appearance” of the goods they are transporting, which are often hundreds of kilos of bags and packages, each of them labeled with a name.

To make the Tunisian customs officers turn a blind eye on their illegal business, the transporters pay extra money to the customs officers, Moncef tells inkyfada.

“If you don’t pay, they will have no mercy, they will search your van, declare everything and tax you so much more”, he says.

Several transporters and former transporters confirm that in order to get through customs control, they often give gifts or extra money to the officers to reduce their waiting time or the amount of taxes and fees that they have to pay.

Faced with these allegations and after the Tunisian customs refused to give an interview to inkyfada, Salma Kalamoun declares via Email: “Our relevant control services exploit the information received about bribery attempts and operations immediately and in case of confirmation of the information, sanctions will be applied which vary from a reprimand to isolation from work.”

On the other side of the Mediterranean, the same rules are supposed to be applied. Mongi Harbaoui, press officer at the French customs, tells inkyfada that just like in Tunisia, commercially transporting goods into France is only possible for someone who has registered his business and has obtained an official permission to transport. At the customs office, the transporter then would have to pay the relevant fees and taxes for the goods that he is bringing into France.

However, none of the transporters that inkyfada has talked to mentioned having had any problems while transporting goods from or to European countries. Moncef confirms that European customs officers never bug the illegal transporters and rarely even control their vehicles.

Not only the Tunisian customs seem to be turning a blind eye on the illegality of the transporter’s business.

“They will ask if you are transporting cigarettes or shishas and that’s about it”, he says.

Legally registering their business would not be profitable for most private transporters, according to Moncef. “If we want to work the official way, transporters residing and declaring their work in Europe will get taxed way too much and lose money”, he says. For him, the bureaucratic hurdles are also a part of the problem when it comes to legalizing one's business as a transporter. “The Tunisian administration is so hard to deal with, they’ll ignore you or make you do unnecessary stuff”, he says.

Despite this, there are a few transporters that try to work within the legal framework by registering a business nonetheless. Before accepting any packages or goods, they make their customers fill in a form with their personal information as well as a detailed list of the items they are sending. With this list, they are keeping their work legal but also protecting themselves. Because by having a legal business and a license as a transporter, the responsibility for the goods they are transporting falls on their customers. In the worst case, this can prevent the transporter from being detained at customs if the goods are confiscated.

A risky business

“There was this woman who wanted to send some things with me to her friend that lives in Tunisia. She gave me a cat house that was sealed and wrapped very tightly, which is why I couldn’t open it. At the customs in Tunisia, they x-rayed it and saw that there was something inside. The officers opened it and found rolling papers, around 50 packages”, Marwene*, a former transporter recalls.

“They kept emptying the cat house and I kept thinking to myself that they will find something else in there, that the woman sent something else with me other than only rolling papers”, Marwene says. When talking about “something else”, he means “drugs”, and adds: “I would advise every transporter to open everything before transporting. It takes a lot of time, but you should do it because otherwise you'll be screwed when you are in Tunisia”. The possession and use of illegal drugs in Tunisia is highly repressed, with the law on Narcotics requiring a minimum sentence of one year in prison for any person found guilty of these charges

Moncef, who has worked as a transporter for 27 years, confirms that the risks for transporters has increased recently, with more and more customers smuggling drugs and medication by hiding them in the packages and goods that they are sending. The transporters therefore have to search everything thoroughly to make sure they are not unknowingly smuggling illegal goods. Some transporters allegedly even use drug sniffing dogs to be extra sure that they are not unknowingly transporting drugs.

One former transporter tells inkyfada: “I have three or four friends who are also transporters and who were in prison because of their customers. One of them for 34 months, another for 18 months”, he says.

“People hide things in doors, washing machines, fridges, blenders, everywhere. A friend of mine recently found drugs in an electric scooter, in the place of the batteries”, he adds.

Because they are cheaper and faster, private transporters are thus an alternative to an official postal and transport system that often fails to meet the needs of its customers. However, the lack of regulation of private transporters also carries certain risks for both the customers and the transporters.