Friday, February 4, 2022. For Selim Khrouf and I*, this date is important. Today, these two Tunisian doctors, based in France, receive the results of their Knowledge Verification Tests (Épreuves de Vérification des Connaissances) or "EVC". Both of them received good news. Their names are on the main list of their specialties, oncology and general medicine respectively. This first success allows them to pursue their final goal: the equivalency of their Tunisian diploma, and registration to the French Medical Council.

This is the second time I have taken this exam. "Last time, there were 1300 candidates and 280 spots. I was 0.45 points away from the last average grade," she recalled. If she failed in last December's session, the young woman was considering a complete career change from medicine to literature, as this was her last chance.

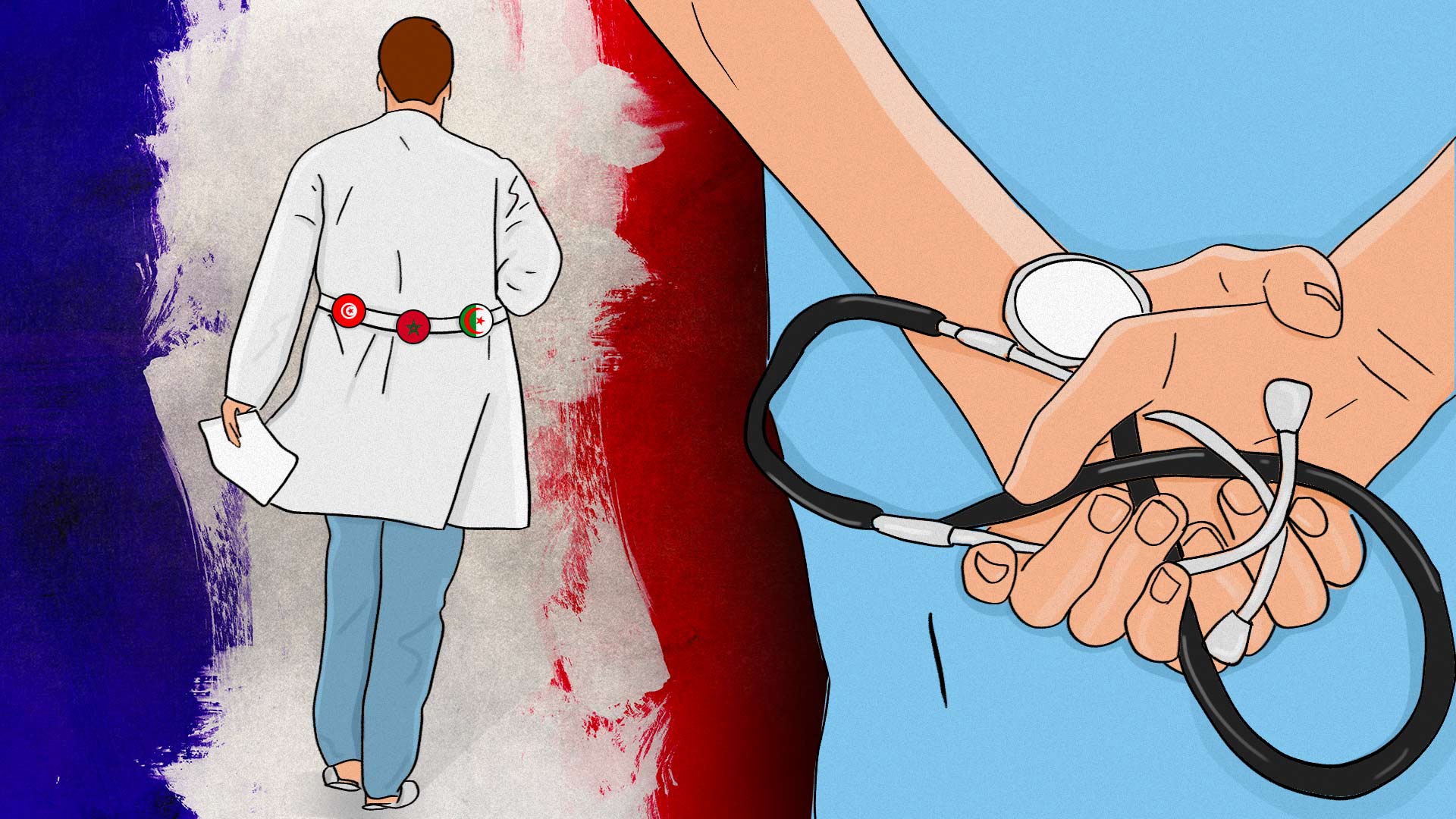

These EVCs, which are compulsory for all people with diplomas from outside the European Union who wish to work in France, are in fact a true competition, known for its complexity. Although Tunisians have the highest success rate, more than half fail.

But these tests are only the beginning. Once they pass, candidates are required to work for two years in a department of their specialty and then sit for a final exam before a licensing board.

This long process ensures that only the best are selected, and provides French hospitals with a qualified, inexpensive workforce that is ready to reinforce their staff in less attractive areas. "France is currently experiencing a structural deficit in terms of the number of doctors," explained Philippe Cart, Head of Division at the Charleville-Mézières hospital and President of the Hospital Radiologists' Union.

"Through this system, we basically allow hospitals to operate with people who get paid less."

Crash test year

Immediately after receiving the EVC results, successful candidates have seven days to submit their assignment requests. In the past, they could negotiate their integration and salary directly with the relevant services. But, a reform in 2020 made this new batch of candidates the first to experiment with a far more rigid system: the available services are now selected in advance by decree and the assignment is determined based on their wishes as well as their rank in the exam. Remuneration is now fixed. " Before, it was possible to receive a very good salary in exchange for going to a center located in a medical desert ", said Selim Khrouf.

With the reform, all those concerned will be paid 2 905,25 € per month for two years. That is, a little less than 66% of the salary of a beginning French hospital doctor.

Officially, this reform should allow for better regulation of equivalency procedures and help avoid abuses, as explained by Nefissa Lakhdara, General Secretary of the SNPADHUE, a union that defends the interests of doctors with diplomas obtained outside the European Union. " In the past, the assignment to a service was done as part of private recruitment, directly between the practitioner and their supervisors. This led to some institutions only running with PADHUEs (editor's note: Doctors with non-EU diplomas)."

Mounir Bouzgarrou is familiar with the challenges of this old system. Now a radiologist at the Bordeaux University Hospital, he came to France in the 1990s to finish his specialty studies. " It was a bit complicated back then," he recalled, "I was supposed to return to Tunisia after graduation."

To avoid this, he managed to get hired as an individual contractor in a service that was in demand. 15 years of trial and error followed, from one temporary assignment to the next, for a salary that he himself described as " ridiculous ". " I used to earn 2200 euros working from 7:30 am to 7:30 pm. My [French] wife, a hospital practitioner in psychiatry, who worked two hours less than me each day, made 4000," he said. However, according to the legislation, psychiatrists and radiologists are on the same salary scale. This experience left him with few good memories: "You are poorly paid, poorly considered, and above all exploited", he stated.

There is no guarantee that these practices will stop with the new reform. The pre-selection of available services is another way for French medicine to ensure that foreign practitioners will go where they are most needed: in poorly staffed establishments, medical deserts, and the least attractive urban areas. "Now, the Regional Health Agencies survey hospitals to find out where the needs are," explained Nefissa Lakhdara.

Thus, out of the 40 emergency medicine positions open to successful EVC candidates in Ile-de-France, 27 are found in the four departments with the lowest medical density. The city of Paris, which has the highest number of doctors per capita in France, offers only one.

This transition period has lasting consequences on the settlement of doctors of foreign origin. In 2021, according to the National Council of the Order of Physicians (CNOM), while 6.8% of the new members of the Order had obtained their degree outside the European Union, their proportion rose to 40% in certain low-medical-density departments, such as the Aisne or Seine-et-Marne. In contrast, French physicians, having no constraints in their settlement after their studies, usually avoid these regions and tend to gravitate towards the most attractive ones: the Atlantic seaboard departments, one of the areas with the largest proportion of French physicians, are also the ones with the highest medical density on the national scale.

This low accessibility to metropolitan areas troubles I, who has made a life for herself in the Paris region, where her husband works as a radiologist. "If I have to make the tough decision to move my whole family, knowing that we only have two months between the results and the beginning of the assignment, it will naturally be very stressful", she said with apprehension. The decision is fraught with risks: in case of rejection, her success in the exam will be wasted.

“We're just here to work"

Another concern of the successful candidates is the working conditions during these two years. "When this new status of associate practitioner was introduced, we learned that there would be no training days scheduled," said Nefissa Lakhdara. "This came as a surprise to us, because in some cases, training is mandatory in order to practice. People may have to take time off work to do it. This is strange given that the CNG has defined this period as a " skills consolidation program ". For Selim Khrouf, the conclusion is crystal clear: "in fact, we are just here to work".

This maximum profitability from foreign doctors often begins long before the EVCs. Indeed, entering the equivalency process is only necessary for them to work in their own practice, and is not required of trainees. Tunisian graduates often seize the opportunity of the " advanced training course " to first set foot in France. During this training, they are often used as manpower by some struggling establishments for tasks that do not correspond to their level of education.

Selim Khrouf, who was doing his in the oncology department of the Melun hospital, considers himself fortunate. "I was carrying out activities that matched my level, but my hospital is an exception because it's quite small," he affirmed.

"If you visit certain Parisian hospitals on weekends, you will only find foreign practitioners running the emergency room", confirms Mounir Bouzgarrou.

However, despite the intensive use of foreign interns, the French administration often limits their settlement, as Selim Khrouf reported. "I had landed the first internship in Drôme, all parties were in agreement," he said. "But the prefecture denied my settlement without any explanation, suspending my procedures and my visa application until I found a new one".

Another stigma: the recent reform regarding the mandatory two years in hospital following EVCs was originally intended to make foreign doctors carry the title of "associate practitioner in integration," according to Nefissa Lakhdara. "It's crazy, it would have sent a really bad message to all parties involved," she commented. "We're talking about people whose integration work has already been done, who work and often have families in France." Eventually, the title was shortened to "associate practitioner", but this symbol feeds a certain feeling of discrimination, especially with respect to foreign doctors from the European Union. These physicians benefit from much faster procedures and even the possibility of practicing after a simple review by a committee. " For a Polish or Romanian doctor, even a less competent one, it is possible to go on Monday morning to the Council of the Order, and to be registered a week later", said Philippe Cart.

Start somewhere else?

Some Tunisian doctors end up abandoning France as a country of emigration due to these inequalities. "I have a lot of friends who have left for Switzerland or even Germany, despite the language barrier", said I. "They were ready to overcome it, for the prospect of a better life". The young woman mentioned the salaries, but above all the consideration, which she said was greater.

"I know two professors who refused to be the back-up for a French department, and who left for the U.S.", recalled Mounir Bouzgarrou, Since then, they have organized a meeting to encourage doctors from the Maghreb to complete their year of specialization over there rather than in France, since merit is more highly valued there. Merit also comes at a cost: to access specialty studies in the United States, a foreigner must first sit for two exams, each costing about 1000$, or 5705 dinars in total.

Although the complexity of the equivalency process affects the choice of destination for Tunisian doctors, France remains one of their preferred destinations. Figures are scarce, but according to a study conducted in 2019 involving three classes of family doctors from the Faculty of Medicine in Tunis, France is their second most preferred emigration destination, after Germany.

Selim Khrouf believes that this is due not only to the lack of a language barrier since medical studies are in French, but also to the networks that students have in institutions in this country. "It's a system where we know the tricks of the trade," he explained, "those who leave bring back the next ones. When you go somewhere else, it's an adventure, you can waste a lot of time."

So, to be on the safe side, these young doctors are willing to endure many sacrifices and hardships in order to obtain equivalency in a familiar environment. " They tell us quite plainly: 'these are the rules of the game, either you accept them and come, or you go back to your country'," said I. "It's disgusting, but what choice do we have? They know very well that it's unbearable in our country, and that the number of applicants is on the rise." Indeed, in 2012, 592 Tunisians applied for EVCs. In four years, this number has almost doubled, with 1036 candidates in 2016 and 1375 in 2018.

For I, this exodus is a tangible reality. "All my close friends, or at least those who were able to leave, are in France or Germany," she said. Selim Khrouf, deeply attached to his country of origin where he witnessed the revolution during his student years, revealed what made him change his mind. " It was obvious to me that I wanted to practice in Tunisia, to teach in the same university where I studied. But we are confronted with a deteriorating economic and political life, and above all, with the harsh reality of the field," he explained.

I even went as far as to say: "In Tunisia, the working conditions are reminiscent of wartime medicine, we were all disgusted". With a salary of no more than "4500 dinars" in the public sector, or slightly more than what they would receive as trainees in France, the choice to emigrate is quite tempting, according to Selim Khrouf. "Had we been valued for our skills, we would have stayed ", affirmed the young woman.

Noureddine Ben Abdallah, Secretary General of the Union of Doctors, Dentists and Pharmacists of Public Health, who called for a strike on January 25, strongly agrees. According to him, more than 50% of young Tunisian graduates end up going abroad. "It's going to be a big problem: we have doctors who are retiring and they need to be replaced," he explained.

“Both the working conditions and the recruitment of contract doctors are causing people to leave," he says. "We are asking for their tenure so that they can work permanently."

Although the unionist believes that, thanks to his action, "the message has reached the public authorities", I is much more skeptical. "When the EVC results come out, everyone cries: 'look, 900 doctors are leaving for France'. But in fact, the Tunisian healthcare system does nothing, it's getting from bad to worse," she said. Statistics provided by Nizar Laâdhari, Secretary General of the National Council of the Order of Physicians, to the fact-checking site Tunifact, indicate that in 2020, nearly 17% of newly registered members in the Tunisian Order had already prepared an emigration file.