At 10am, in Hammam Chatt, six planes carried out successive raids on several PLO facilities. The operation itself lasted only a few minutes, but the damage was colossal. In addition to the killed and wounded, the material damage was estimated at almost 6 million dinars. The preciseness pointed to great familiarity with the area: only houses where PLO members lived or worked were hit, and most were leveled* to the ground.

Despite the level of precision, the operation (which was targeting a meeting of PLO officials, including the then President Yasser Arafat), missed the mark. Scheduled for 10am, the meeting ended up being delayed at the last minute due to the fact that some executives from abroad were unable to get to Tunis in time. Yasser Arafat, who instead had gone to attend a tribute to former Tunisian minister Abdallah Farhat at the Kasbah, was in fact not in Hammam Chatt.

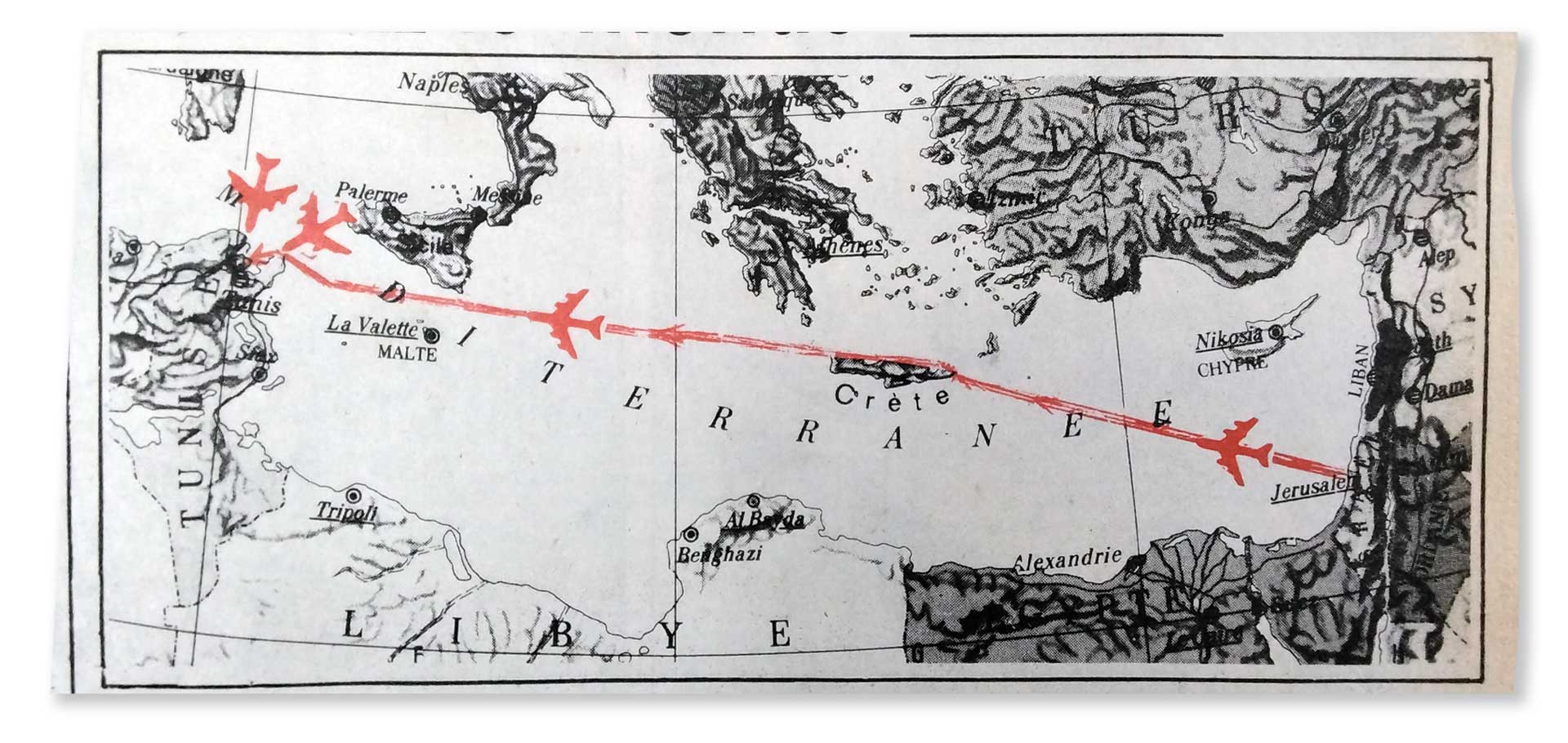

"The supposed itinerary of the Israeli squadron... a crossing of nearly 4800 km (round trip) right under the nose of the sixth fleet of NATO bases" (Le Temps, October 2, 1985), National Archives of Tunisia (Fr).

The bombing came after former Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres had threatened to brand the PLO and Yasser Arafat as terrorists, and vowed revenge for the assassination (not claimed by the PLO) of 3 Israeli nationals in Cyprus on September 25 earlier that year. The PLO - an organisation in exile and fragmented between several Arab countries since they were forced out following the Israeli invasion of South Lebanon in the summer of 1982 - was welcomed by Tunisia where they subsequently set up its headquarters*.

"We are a people used to standing our ground"

Deadly attack creates chaos in Hammam Chatt:

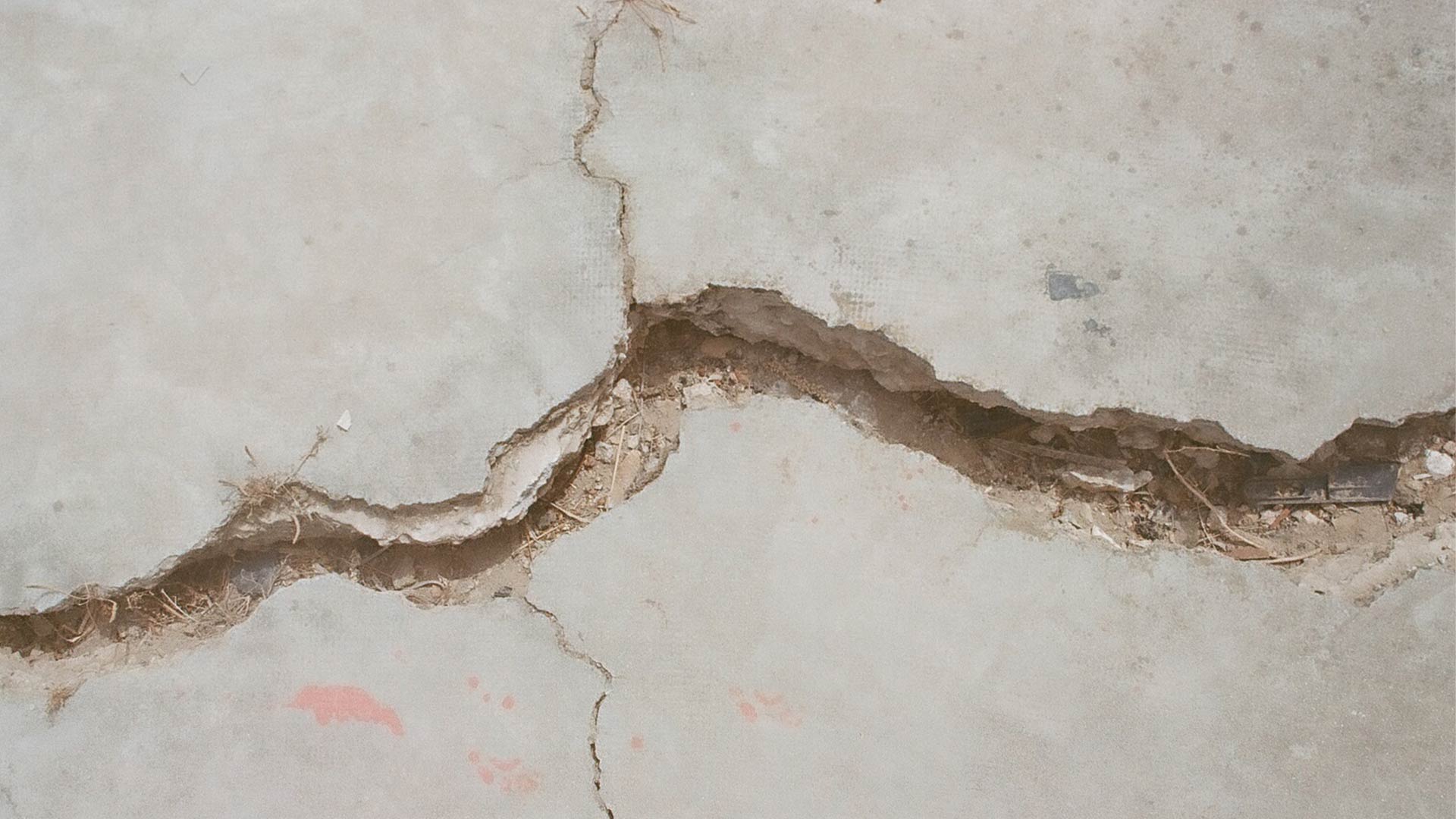

"A heap of scrap metal, beams, concrete, bits of wall, debris, chairs, remains of telephones... Scattered pieces of newspapers and documents, burnt cars, debris strewn on the ground [...]. Doctors, nurses, soldiers, policemen, national guards, civil protection agents, rescue teams, amidst the rubble, organising themselves [...] to dig out the people buried under tons of ruins [...]. Ambulance sirens, the roar of cars, the deafening noise of bulldozers sweeping away the debris, orders [...] coming from everywhere" (La Presse, October 2, 1985).

National Archives of Tunisia

Due to the shock, one of the PLO buildings was transformed into a gigantic hole that filled up with water like a well*.

"Many Palestinians were sitting under the shade of a tree counting the victims of the attack. Some in tears, others covered with bandages, all [...] took part in first aid amidst the rubble and burnt-out cars. A doctor told us that half an hour after the bombing, there were several bodies, some of which had been decapitated or had lost their torso." (Le Temps, October 2, 1985, comments from a journalist)

"The sight of the dead and wounded caused several people to faint" (Le Temps, October 2, 1985, comment from Yasser Arafat's photographer)

"When we arrived at the scene, the sight was heartbreaking. Dead bodies were strewn on the ground. Some were torn apart, even decapitated. It was impossible to know the nationality and identity of the victims. The majority were young men. It was horrible" (Le Temps, October 2, 1985, a nurse's* comments)

Most of the Tunisian victims were security guards and some were women who were responsible for cleaning the various offices and homes of PLO members.

In total, four buildings were levelled to the ground: the headquarters of Force 17 (Yasser Arafat's security service), one of Arafat's houses*, the telecommunications office and the prison where the organisation kept prisoners. The prisoners were reportedly killed by the bombs.

Photograph taken on film in Hammam Chatt by Fakhri El Ghezal for this article.

Among the heaps of ashes and stones, a journalist from Al-tariq Al-jadid (a left-wing opposition newspaper), approaches the former prison. "Even among the revolutionaries, there was a prison", he notes before continuing:

"An image I will never forget: a leg raised to the sea, the leg of a prisoner who tried to flee as he felt the bombs annihilate the walls around him, but only his leg managed to free itself" (Al-tariq Al-jadid, October 5, 1985)

Yasser Arafat arrives with his guard around 1.30pm to see the damage. Rescue operations continue until late afternoon.

National Archives of Tunisia

Despite the utter desolation, a Palestinian woman asserts her determination in front of the journalists:

"The enemy is astonished that we are rising from under the rubble with a new soul. We do not have the military apparatus that he has but we are a people used to standing our ground." (Al-tariq Al-jadid, October 5, 1985)

"State terrorism"

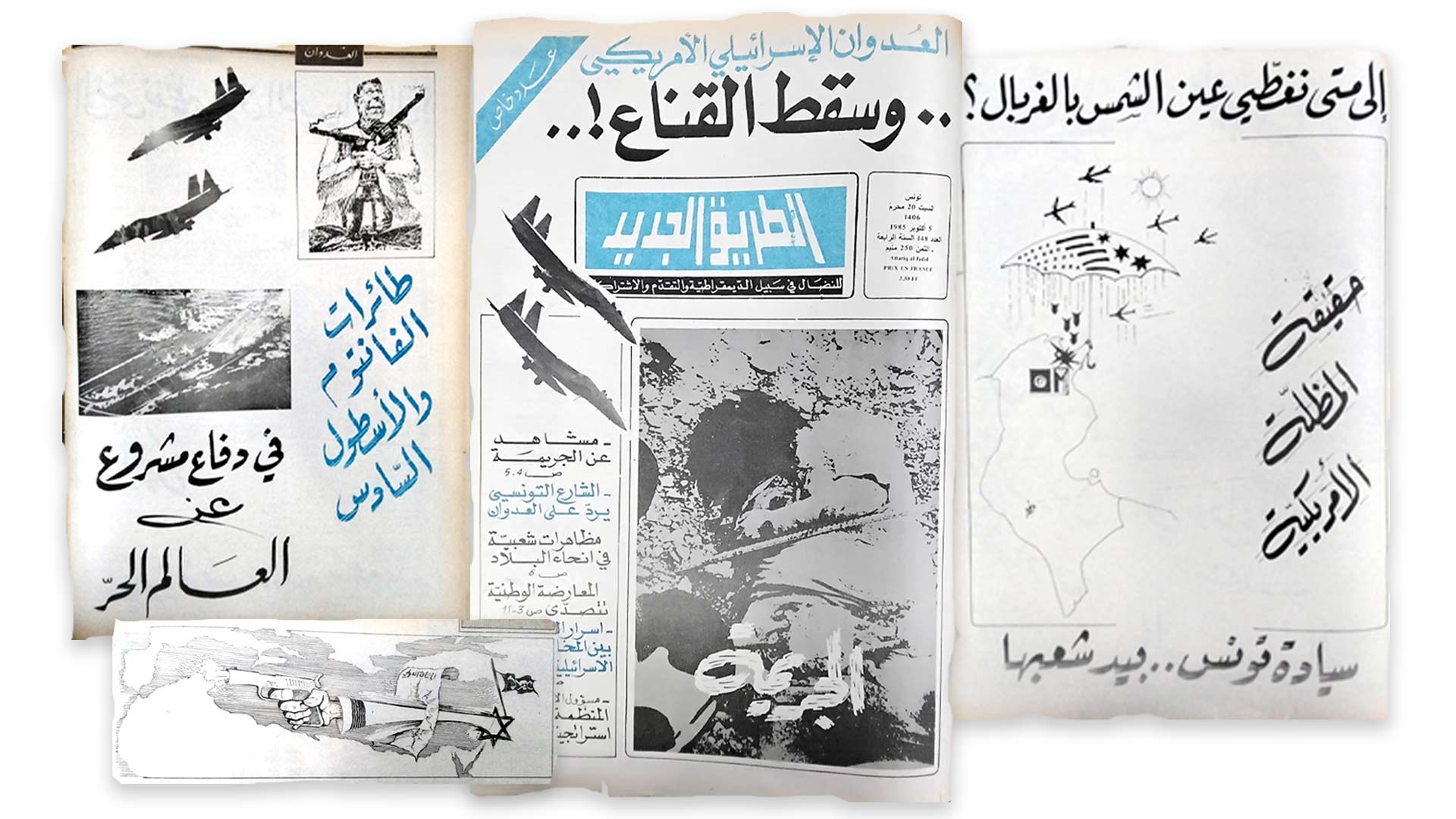

Described in newspapers the following day as a "barbaric raid", "state terrorism" or "Nazism", the bombing was initially covered up by Tunisian radio and television.

The US assistance to this Israeli operation makes the treatment of the information sensitive in a context where the American power until recently declared its unwavering support to Tunisia in the face of Libyan military threats*.

However, the fighter planes deployed by the Israeli occupation army to attack Hammam Chatt are part of the dozens of planes supplied by the United States to their ally (these F-16 planes had already been used in the Israeli raid on a nuclear reactor in Iraq on June 7, 1981). Moreover, the fact that the bombers flew from Tel Aviv to Tunis shows that the way had been cleared, despite the presence of the American fleet in the Mediterranean.

Moreover, the Israeli occupation army's bombers were reportedly refuelled by American planes along the way. Last but not least, US President Ronald Reagan described the military operation on Tunisian territory as "self-defence", thus expressing the United States' full support for the bombing, which was illegal under international law.

All this created great confusion within the Tunisian government, as they had thought they had unwavering support from the United States. On October 1, the official Tunisian media were embarrassed and struggled to relay the full story.

Opposition newspapers, such as Al-tariq Al-jadid, protested against this media response, which they considered to be superficial. On October 1, during the 1pm news, Tunisian radio and television did not reveal the origins of the planes, and remained silent about the American stance. The opposition newspaper ridiculed the content of the national channel's report:

"11am: music programme; 12pm: brief news, nothing on the attack; 1pm: unknown aircrafts attacked Hammam Chatt, no further details; 8pm: the paper reveals the identity of the bombers and holds the international community and especially the countries with friendly relations to Israel responsible, without mentioning the US. Instead, it highlights the solidarity of countries with friendly relations such as Italy and France."

National Archives of Tunisia

One explanation for why Tunisian citizens were kept in the dark for hours would be - in addition to the complex relationship with the US - President Bourguiba's nap:

"But as this was news of the utmost importance, the text, as was the practice at the time, had to be submitted to the Prime Minister. The latter was so cautious as to ask for the green light from the Presidency. In the meantime, news agencies were flooded with reports from Tel Aviv claiming responsibility for the attack. [...] At the time, we were in the middle of the end of the reign and nobody wanted to take the responsibility of telling Bourguiba the bad news. So much so that when we agreed on the text, the president was in bed for a nap. We had to wait for him to wake up. So while the whole world was focused on the news of the day, Tunisians were kept in the dark about a crucial event that had just taken place in their country. Both radio and television, which were required to carry the official agency, did not say a word. It was only at 5pm, after Bourguiba had woken up, that the news was finally published, but in the worst possible way [...] This was undoubtedly the failure of the century for Tunisian media."*

"Mourning and indignation"

The lack of information and the tense situation with Libya meant that many people initially thought that the attack came from them. Once the source of the attack was revealed, the news spread like wildfire.

Amel Ben Aba, a feminist activist who had gone to Bizerte to attend the arrival of PLO members in 1982, remembers having a violent haemorrhage when she found out, alongside her companion (a Palestinian painter and PLO member), that Hammam Chatt had been bombed. "I was bleeding so much that it affected me. How could they do such a thing? It was unbearable, I experienced it as something terrible", she recalls in an interview with inkyfada.

Photograph taken on film in Hammam Chatt by Fakhri El Ghezal for this article.

For dissenting journalists, the precision of the deadly strikes was astonishing:

"There are many questions about the extent to which Zionist and American intelligence is implanted in our country and about the effectiveness of our own intelligence services if it is anything other than monitoring Tunisian opponents." (Al-tariq Al-jadid, October 5, 1985)

Between anger and accusation, the position of the government and the official media became clearer. The day after the bloody strike, the Tunisian government denounced the act as contrary to " the norms of international law and the UN Charter" and reiterated that "Tunisia will not abandon its attitude of continuous support for all just causes". (La Presse, October 2, 1985). With this in mind, the State allowed demonstrations against the attack to take place:

"The demonstrators reaffirmed the Tunisian people's active solidarity with the Palestinian people in their just struggle against the Israeli oppressor. The demonstrations took place in a calm atmosphere and the police forces did not have to intervene.” (Le Temps, October 5, 1985)

However, far from the official version that was laced with lyricism, the facts reported by the opposition media nuanced the reality of this moment of union.

The newspaper Al-tariq Al-jadid reported that student movements against government silence took place the day after the attack. About 2000 demonstrators gathered at Passage (in downtown Tunis). A second demonstration started from the Medina and the police were apparently heavily represented. The presence of BOP (public order brigades) was, according to the newspaper, intensified around the American cultural centre [formerly located at the corner of Avenue de France and Rue Jamel Abdennasser]. Other regions such as Gabes or the Sahel were the scene for workers' and communist mobilisations, etc. The UGTT trade union centre also organised a demonstration.

National Archives of Tunisia

On October 5, a demonstration of "mourning and indignation" organised by activists - mainly belonging to the core group of the Tunisian Association of Democratic Women - sets off from Avenue Bourguiba. The activists are dressed in black and walk slowly "in an impressive silence", bearing slogans and Tunisian and Palestinian flags. The flags were destroyed by the police, who reportedly used their sticks to abuse the demonstrators (Al-tariq Al-jadid, 12 October 1985).

This demonstration took place on the same day as the burial of the bomb victims, an event that was somehow hijacked by the authorities, according to the independent newspaper Erraï:

"The funeral of the victims of the US-Zionist attack was not on par with the event. The public was denied access to the Hammam Chatt starting point and journalists were denied access to the cemetery [in Hammam Lif]. Police officers prevented people from passing the cars with coffins. Some people were able to pass due to pressure and insistence, but they faced a new obstacle: the gate of the cemetery was shut after the coffins and politicians had passed*. Immediately after the burial, the police asked to remove the Palestinian flags and photos of Arafat and to 'return to normal'." (Erraï, October 6, 1985)

Photograph taken on film at the Hammam Lif cemetery by Fakhri El Ghezal for this article. It was impossible to access the cemetery.

The authoritarian state, careful to prevent demonstrations on national issues, allowed mobilisations in support of Palestine, whilst controlling them. The defence of the 'cause' was thus in a sense a delicate equation between allowing protest and regulating it. Seemingly without direct impact on the national territory, pro-Palestinian activism was tolerated and even picked up by the state. The magnitude of the bombing on October 1, 1985, upset this equation, because by suddenly bursting into Tunisian national territory, the Palestinian question became a central one.

Tunisia filed a complaint with the UN following this violation of its national sovereignty. The negotiations subsequently led to Resolution 573, in which the Security Council "strongly condemns the act of armed aggression perpetrated by Israel against the territory of Tunisia, in flagrant violation of the Charter of the United Nations and international law and standards of conduct". The United States abstained from voting.

Following the Hammam Chatt attack, the PLO's presence in Tunis started to considerably reduce. Condemned without any consequences, the Zionist state resumed its aggressions. Abu Jihad (head of the military branch of the PLO) was assassinated at his home in Sidi Bou Said on 12 April 1988 by an Israeli squad, in the presence of his wife and children. Forensic doctors found 75 bullet holes on the body of the former military leader.

The PLO's relations with the following Tunisian president Ben Ali became increasingly strained, until the Palestinian organisation ultimately left Tunisia in June 1994.