This incident is far from unique. As the string of demonstrations began on the 14th of January 2021, multiple human rights organisations have reported a wave of arbitrary and abusive arrests, violating the rights of those arrested, both during and after the protests. On the eve of the new year, the Public Prosecutor’s Office nevertheless authorised hundreds of arrests, overcrowding detention centres, despite the exceptional health care constraints that are facing the country.

Mehdi Barhoumi recalls the events of that night: “As usual, we agreed to continue the political discussion at one of our houses after Saturday’s demonstration. We were having a lively conversation, but little did we know that this debate would be held against us later on.”

“Without a warrant, warning or explanation, a security guard stormed into my house and brought us outside to arrest us in full view of everyone. He even handcuffed one of us while one of the officers was shouting: ‘So you dare to insult the police unions! You will pay the consequences’“, Mondher Souodi recounts.

A protester forms the victory symbol with his hands cuffed at the “Liberate Tunisia” protest on March 6, 2021. Photo credit: Issa Ziadia

In the middle of a troubled social, economic, and public health context, this incident brought back the debate about the minimum threshold of suspicion required to detain the suspects, and the discretionary power of the prosecutors to sentence based solely on police reports.

This debate is all the more important after “multiple transgressions” in the process of detention, as reported by Human Rights Watch. This raises questions both about the role of the public prosecution and the judicial authority in using legal arsenal provisions to impose freedom depriving sentences.

On the same subject

“24 HOURS IN PRISON IS ENOUGH TO DESTROY AN ENTIRE LIFE”

Mehdi Barhoumi describes his experience in a detention centre as “lacking even the minimal health conditions”. “The number of detainees kept increasing throughout the entire Sunday. Even though there was no more space in the small, crowded room, new detainees kept pouring in, defying all health protocols. This is an example of the hypocrisy of a state that on the one hand imposes oppressive measures to prevent the virus from spreading, and on the other: overcrowds detention centres in disregard for the health of the detainees.”

In response, Mohsen Al-Dali, the official spokesman for the Court of First Instance (Tunis 1), deflected responsibility for implementing pandemic precautions in detention centers, and instead holds the government accountable. ”Health protocol in detention centres is the responsibility of the Ministry of the Interior. If police reports indicate that a hundred individuals committed acts of vandalism, the public prosecution is obliged to detain all of them.”

“When national security is at stake, the Public Prosecutor’s Office resorts to arrests until order is restored. When it comes to health protocols, it is the government that has to ensure that these are respected in detention centres.”

- Mohsen Dali, Official Spokesman for the court (Tunis 1)

In addition to the precarious health conditions, Mondher Souodi recalls the psychological impact of his arrest: “We were taken to the first room which, according to other detainees, was the most comfortable one”, he sarcastically adds that “in this luxurious room, the violence was mainly psychological. It was almost impossible to distinguish night from day because of the poor lighting and meal times, in addition to the extreme overcrowding. There was not enough space to move around, and the proximity of the bunk beds meant that we had to sleep up against each other.”

The public prosecutor justifies the “usefulness” of the huge number of arrests that followed the recent protests by claiming the necessity to “manage public security”. According to him, “the public prosecution wanted to ‘calm’ the disorder through arrests”. He also admits to “authorising the detention of multiple individuals ‘for several days’ until the court of first instance issued reduced sentences”.

In order to temporarily defuse the protests, the public prosecution then intentionally overcrowded the detention centres with youth, whilst relegating the responsibility to find a solution to the judiciary authorities.

One of many demonstrations that took place in the capital to protest against the economic and social conditions earlier this year, Paris Avenue, January 23, 2021. Photo credit: Issa Ziadia

“The public prosecution judges think that their role consists of filling up detention centres, particularly the one in Bouchoucha”, lawyer Adnane Labidi tells inkyfada, analysing the public prosecution’s way of applying the law “according to a philosophy of protecting civil order”. Mr Abidi believes that “such a philosophy comes from notions inherited from previous centuries. The modern conception of criminal procedures is based on protecting the individual human being, which naturally ensures protection of civil order”.

According to the Tunisian constitution, the Public Prosecution’s Office carries out its functions within the framework of the general direction of the government's official criminal policy, as part of judicial justice. Under the supervision of the State Secretary for Justice, the Public Prosecutor’s Office is required to monitor the implementation of the law in accordance with the Criminal Procedure Code.

Article 115 of the Tunisian Constitution

[...] The Public Prosecutor’s Office is part of the judicial system, and benefits from constitutional guarantees. The Public Prosecutor’s Office is part of the judicial system, and benefits from constitutional guarantees. The public prosecution judges exercise their functions as determined by the law and within the framework of the State’s criminal policy in accordance with the procedures laid down by the law. [...].

According to the United Nations guidelines, the role of the prosecution is (in absolute terms) partly to ensure proper application of the law, and partly to respect the rights of the defendants and victims. Article 14 from the same guidelines stipulates that prosecutors “must refrain from initiating or continuing the proceedings, or to make every effort to suspend the procedure if an impartial investigation reveals that the charge is unfounded”.

The same article also reviews the possible alternatives for the public prosecution to avoid legal prosecution:

Article 18 of the Guidelines of the Role of Public Prosecutors

Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders

In accordance with national law, prosecutors shall give due consideration to the possibility of waiving prosecution, conditionally or unconditionally discontinuing proceedings, or transferring criminal cases outside the formal justice system, with

full respect for the rights of the suspect(s ) and the victim(s). [...] States should fully explore the possibility of adopting transfer methods [...] to avoid the stigma of pre-trial detention, indictment and conviction, as well as the possible

adverse effects of imprisonment.

Judge Mohsen Dali confirms that “as long as the Public Prosecutor has the freedom to interpret and implement” the public prosecution could suspend the application of certain legislative texts that are no longer relevant to international standards or the 2014 Constitution, until the Penal Code gets updated.

But at the same time, it does not deny the right of the judge to primarily resort to the Penal Code in place. Claiming to preserve public safety, the judge pretends to ignore international standards by saying: "I don't care about international recommendations calling for leniency. Only he who walks on ember can feel it” [local proverb meaning ‘anything seems simple to those who have not tried it’].

“24 hours in prison is enough to destroy an entire life.” - Marc Ancel

In his book ‘La défense sociale nouvelle’ (the new social defense), attorney Adnane Labidi quotes the lawyer and thinker Marc Ancel, commenting on the policy of “systematic deprivation of liberty followed by public prosecution”. He argues that “the Tunisian public prosecution accepts 'quasi-systematically' accepts detention requests submitted by police officers in the first instance, and issues warrants during the investigation in the second instance”, based on personal experience in litigated cases. This raises the question of whether the tendency of the public prosecution to detain people in a "quasi-systematic" fashion, represents the state's official penal policy.

The official spokesperson for the Court of First Instance (Tunis 1) stresses that “there are no general instructions” that are clear enough when it comes to protest-related cases, explaining that the government “does not even have sufficient authority”.

“Detention authorisations are usually the result of a personal reaction and assessment by the judges of the Public Prosecutor’s Office, who are ultimately part of the State. No general instructions have been issued, and the Minister of Justice neither intervenes to instruct nor to prohibit.” - Mohsen Dali

If the automatic tendency to freedom deprivation is not the result of an official penal policy of the government, then, according to Adnen Abidi, it could be "the remnants of a practice that was in place during the period when the police state held the reins of power”.

THE NEGLIGENCE OF THE PROSECUTION IN APPLYING DETENTION REGULATIONS

In the Cité El Khadhra police station, the transcript of the hearing involving Mehdi, Sami and Mondher was drawn up in the light of a complaint that the three young men had attacked the guard of the Dutch Embassy, merely a stone's throw from their home. According to the men concerned, their request for the presence of a lawyer, was denied, after which they were taken directly to the Bouchoucha detention centre.

"Barely two hours had passed since our arrest when the public prosecutor issued the detention authorisation", Mehdi denounces. Commenting on the incident, the lawyer representing the three young men, Hammadi Henchiri, explains that "a security officer entering into a stranger's residence without judicial authorisation is in clear breach of the law and legal proceedings". As a result, "my clients have been deprived of their freedom of movement and housing in the absence of a ‘flagrante delicto’, and without preliminary authorisation from the public prosecutor”.

With regard to "finding a ‘flagrante delicto’ in order to authorise the detention of the three young men", Mohsen Dali, the official spokesman for the Tunis 1 court, recognises the extensive authority of security officers to arrest suspects on the grounds of ‘flagrante delicto’, without a warrant.

Even in cases where the officer is both judge and jury, the prosecution does not verify the ‘flagrante delicto’ before the arrest, but rather afterwards, upon receiving the police report. Thus, if necessary, "if the extent of the damage is not proven, the Public Prosecutor's Office lets us appear before the court at liberty."

“Regardless of the public perception of security officers, my job as a public official is to protect them. It does not matter to me that ‘practices of the police state’ get associated with the Public Prosecutor’s Office.” - Mohsen Dali, Official Spokesman for the court of Tunis 1

"The judicial police officers are responsible for ascertaining the offence and consulting the Public Prosecutor's Office about the detention in writing", explains the official spokesperson for the Tunis 1 court. However, he points out that, in practice, the security guard simply transmits the details to the Public Prosecutor's Office via telephone. If the information available to the public prosecutor relates to an offence for which the person was detained, the security guard is obliged to either send a written consultation about the detention by fax, or go to the court. It is at this point that the Public Prosecutor's Office authorises the detention by whatever means that leave a written record.

The same article also regulates the procedure of judicial police officers when detaining a suspect:

Source: Law n° 2016-5 of 16 February 2016, amending and supplementing certain provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code.

"The security agents at the Cité El Khadhra police station did not notify us of our rights, the charges against us, or the duration of our detention. They even questioned us before our lawyer arrived and went so far as to note in the report that we were waiving our right to legal representation.” This is the testimony of Mehdi Barhoumi on the events following his arrest and what he considered to be in "clear disregard of law no. 2016-5, 5 years after its issuance".

"When I asked one of the agents to inform me of my rights, he sarcastically replied: “Do you want a stripper too?” - Mehdi Barhoumi

The official spokesman for the Tunis 1 court does not deny the numerous violations, but he argues that the Public Prosecutor's Office tries to limit them by rigorously observing the legal regularity of the transcripts*, “transcripts in which the judicial police fail to include the procedures, deeming them void”. Consequently, the judge confirms the prosecution’s initiative to check the legal formality of the transcripts, without presenting a sufficiently efficient mechanism to ensure the veracity of the information provided. He points out that even in the investigation of torture cases, for example, an independent record is drawn up for this purpose, "but the initial transcript remains in effect".

LAWS FROM A TYRANNICAL ERA, IN THE HANDS OF THE PROSECUTION

Following the protests that broke out in January 2021, and after authorising the detention of the protesters concerned, the public prosecutor formulated "vague accusations against the detainees, such as 'violation of the state of emergency', which were intended to charge the individuals without specifying their charges", according to Nawres Douzi, coordinator of the Tunisian League for Human Rights. Within this context, Nawres refers to Decree No. 78-50, regulating the state of emergency, a text that is considered unconstitutional by the DRI due to its "broad restriction of rights and freedoms".

The Tunisian League of Human Rights (LTDH) and Lawyers Without Borders (ASF) have documented the charges against the arrested demonstrators and their respective penalties

According to multiple human rights organisations such as Human Rights Watch (report available here link), the Public Prosecutor's Office has gone as far as to apply certain controversial laws, that they deem to be in breach of international standards of rights and freedoms, in order to manipulate cases and allow for the deprivation of liberty during the course of trials.

This was the case for Sami, Mehdi, and Mondher on Monday the 8th of March 2021, when they were charged by the Assistant Secretary of State with "assaulting a public official through words, gestures, or threats", according to Article 125 of the Penal Code - after having endured 48 hours of detention.

“The vast majority of cases submitted under this article are brought by security officers against citizens in clear abuse of power”, explains attorney Ayoub Ghadmasi.

On the same subject

According to the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights (FTDES), this article is inherited from the colonial era, dating back to 1913, and is “one of the most dangerous articles of the Penal Code that is used to deal with defenders of rights and leaders of protest movements. It conforms with neither the Tunisian Constitution, nor legal action laws, and constitutes a serious threat to universal values of human rights”.

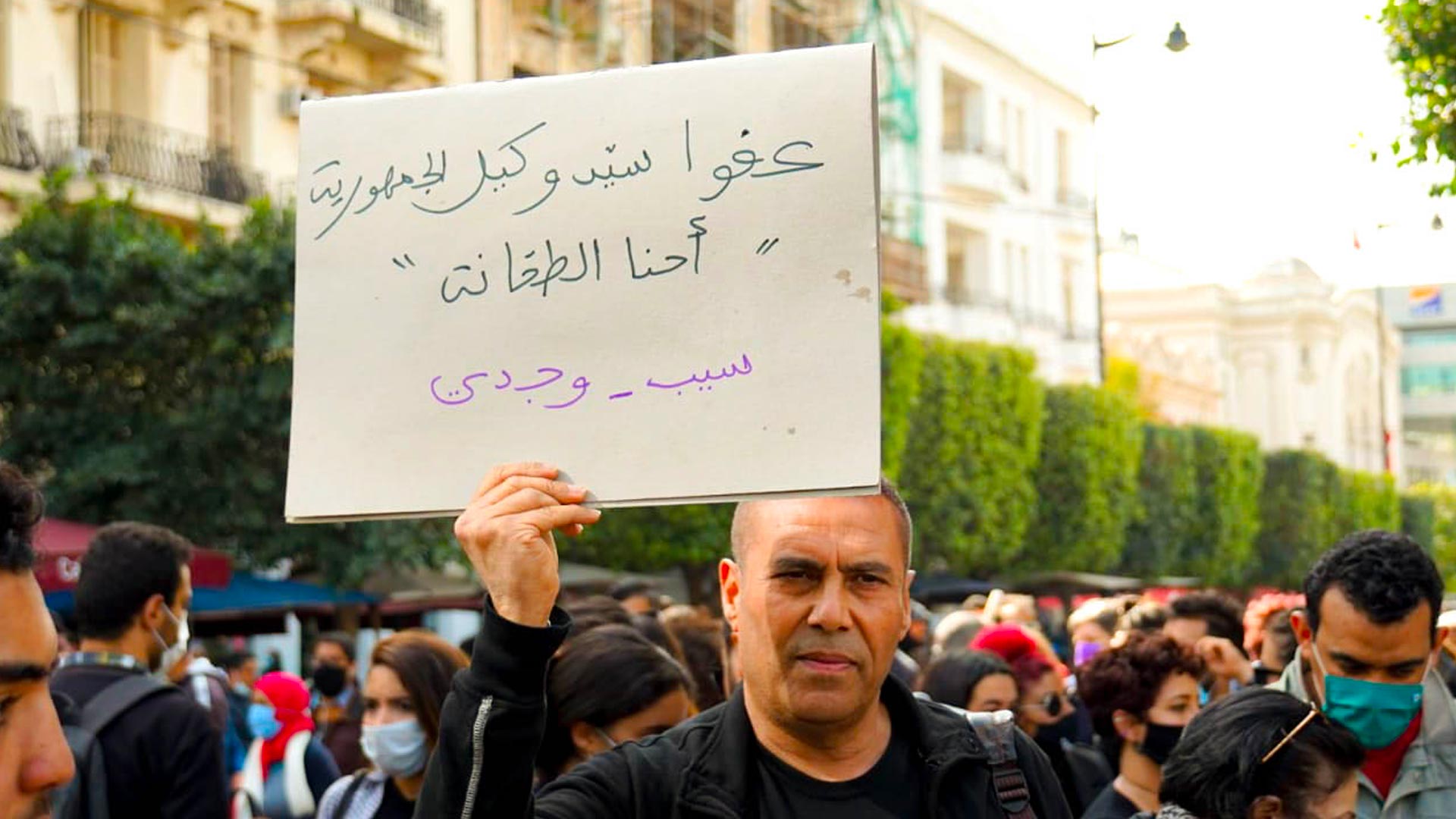

“Excuse me, Mr Secretary of State, we are the villains.” A sign from the “Liberate Tunisia” protest on March 6, 2021. Photo credit: Issa Ziadia

Mohsen Dali, the official spokesman for the Court of Tunis 1, does not take issue with continued application of this article: ”It is inconceivable to proceed on the basis that ‘the Constitution stipulates freedom, so I will not enforce grounds for contempt’. What is currently available to judges are the criminal laws that have not yet been abolished”. He then elaborates by stating that “the constitutional provisions have guaranteed many freedoms, but the Constitution itself does not involve criminal laws. The authorities that are able to terminate the application of these articles are the legislative or constitutional court".

Nevertheless, Me Ayoub Ghedamsi concludes that "the Tunisian legal system, including the Public Prosecutor's Office and the judiciary, is entirely on the side of the police and does not know how to refuse them anything. It is up to the state to decide, as others have done before them, to abandon the application of any unconstitutional charges. Unfortunately, criminal policy in Tunisia is now leaning towards systematic deprivation of freedom of movement, and overcrowding of detention centres."