“ Voluntary homicide preceded by torture and followed by the concealment of evidence and the concealment of a corpse . . . torture resulting in death . . . disappearance and forced detention.” A judge reads out the Truth and Dignity Commission’s (IVD) indictment, which calls a dozen defendants to the stand. None are present.

Over many hours in the crowded courtroom, witnesses painfully testified, slowly reconstructing the final days of Kamel Matmati.

Terror at the STEG

Gabes, Tunisia, 1991. For one year, Mohamed-Ali Ganzoui has served as the chief of special services – more commonly known as the “secret police.” Appointed by Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, his role is to control and prevent all forms of opposition to the new repressive regime.

Over time, the special services spread, establishing units throughout all of Tunisia. In Gabes, the unit is led by two men: Samir Zaâtouri, in charge, assisted by Ali Boussetta, chief of the investigation unit. It doesn’t take long for their team to launch an extended crackdown on islamists — the main targets of the regime — and their close ones.

Meanwhile, in the same town, Kamel Matmati goes to work every day at the Tunisian Company of Electricity and Gas (STEG), where he works as an assistant engineer as well as a unionist for the company. At the time, Kamel was 35 years old, a father, and a member of the islamist party, Ennahdha.

“We lived in terror at the STEG.”

Slah, one of Matmati’s colleagues, testifies at the trial. He remembers the climate of terror created by the police presence at the STEG. “ It wasn’t a workplace, it was a company for state security . . . they had an office in our building.” Over many months, STEG employees become more and more vigilant of the police. Prayer time becomes a source of anxiety. “ Every time, we assumed they would take someone away,” he adds.

Kamel Matmati is being watched by the police. He is the secretary general of the union and has gained respect after defending other employees. As a member of the Ennahdha movement, this role makes him even more of a target. “ We were expecting them to take Kamel away at any moment.”

The arrest

October 8th, 1991*. Noureddine will never forget it. “ I was very close to this great man. We were good friends,” he says during his testimony. In the afternoon, Kamel Matmati is on the first floor of the STEG building. He likes to take his time to perform his ablutions before the prayer. “[Sometimes] he could take an hour. I came out before him,” Slah confirms.

Leaving the bathroom on the way to the prayer room, Noureddine and Slah notice two policemen standing a few meters away. “ We knew them. They worked and lived with us in the company,” Slah recalls. He begins to worry.

“ I wondered if I should go back and warn Kamel, but fear was strangling us at that time.”

A few minutes later, Noureddine hears unusual noises, but doesn’t want to interrupt his prayer. Afterwards, his colleagues greet him with the bad news: “ Brother, they took Kamel.”

Slah, on the other hand, claims to have seen it all. When he comes out of the prayer room, he sees the two policemen surround his colleague. “ One grabbed him by the shoulder, the other by the belt, and they took him away while insulting him.” The policemen force Kamel Matmati down the stairs and out to the parking lot where their car is waiting. They try to force him in, but he resists by clinging to the car’s frame.

At that moment, a taxi stops close by, and the driver leaves his vehicle and heads towards the scene. “ It was Abdallah — we know him well — the worst of informants,” says Slah. He comes behind Kamel Matmati and headbutts him in the back, making him lose his grip. The police control the situation.

A few days later, Noureddine is also arrested under similar circumstances. He will never see his friend again.

Torture at the police station

Ali Ameur has been a doctor at the regional hospital of Gabes since 1986. One day before Kamel Matmati’s arrest, Ameur is also arrested and detained for belonging to the Ennahda movement.

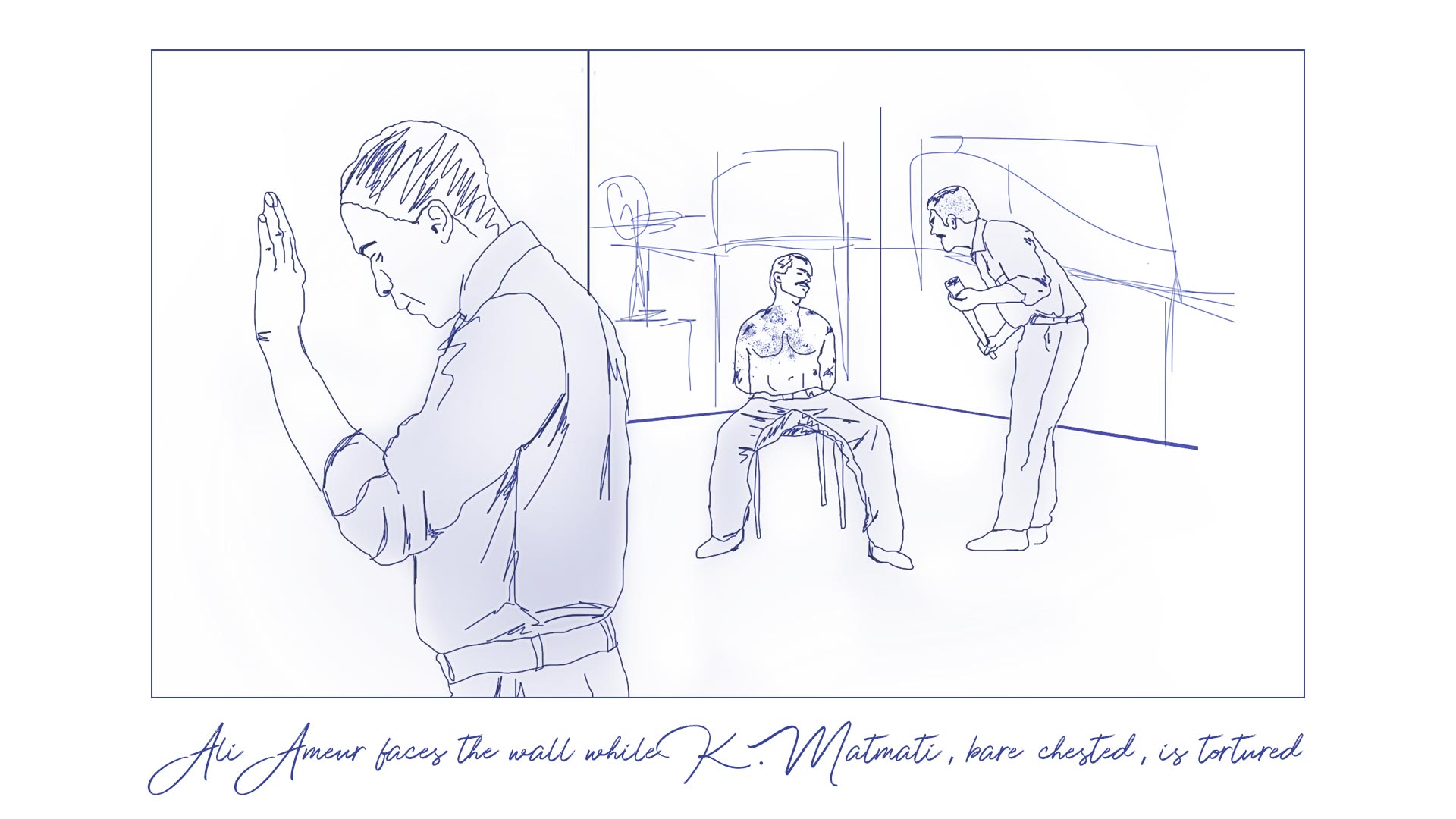

At the witness stand, Ali Ameur tells of his story and of those that were detained with him. Locked up in a room, police officers force them to remain standing with their arms in the air. For more than 36 hours, the doctor stands in this position, is beaten with a stick, forced to sit on a bottle, and is stripped and suspended by his hands and feet — a torture method commonly called “poulet rôti” (i.e. roast chicken). His memory is spotted. " Psychologically, I was destroyed,” he confesses.

The next day, Kamel Matmati is brought to the same cell. Forced to face the wall, Ali Ameur can only hear the baton blows to the unflinching victim.

Some time later, one of the policemen calls the doctor over. “ He told me, ‘Come see,’ and I went. ”He discovers Kamel bare-chested, stunned, and bruised. “ I told them that his arms were broken, and they stopped torturing him and threw him in a corner of the cell.”

It will be a short break for Kamel. When the chief of police arrives, he asks why the policemen had stopped beating the victim. The policemen regurgitate Ali Ameur’s diagnosis, but the chief isn’t moved. The doctor later identifies Ali Boussetta, the chief of investigation, as the one who seizes a baton and begins beating the unmoving victim once again.

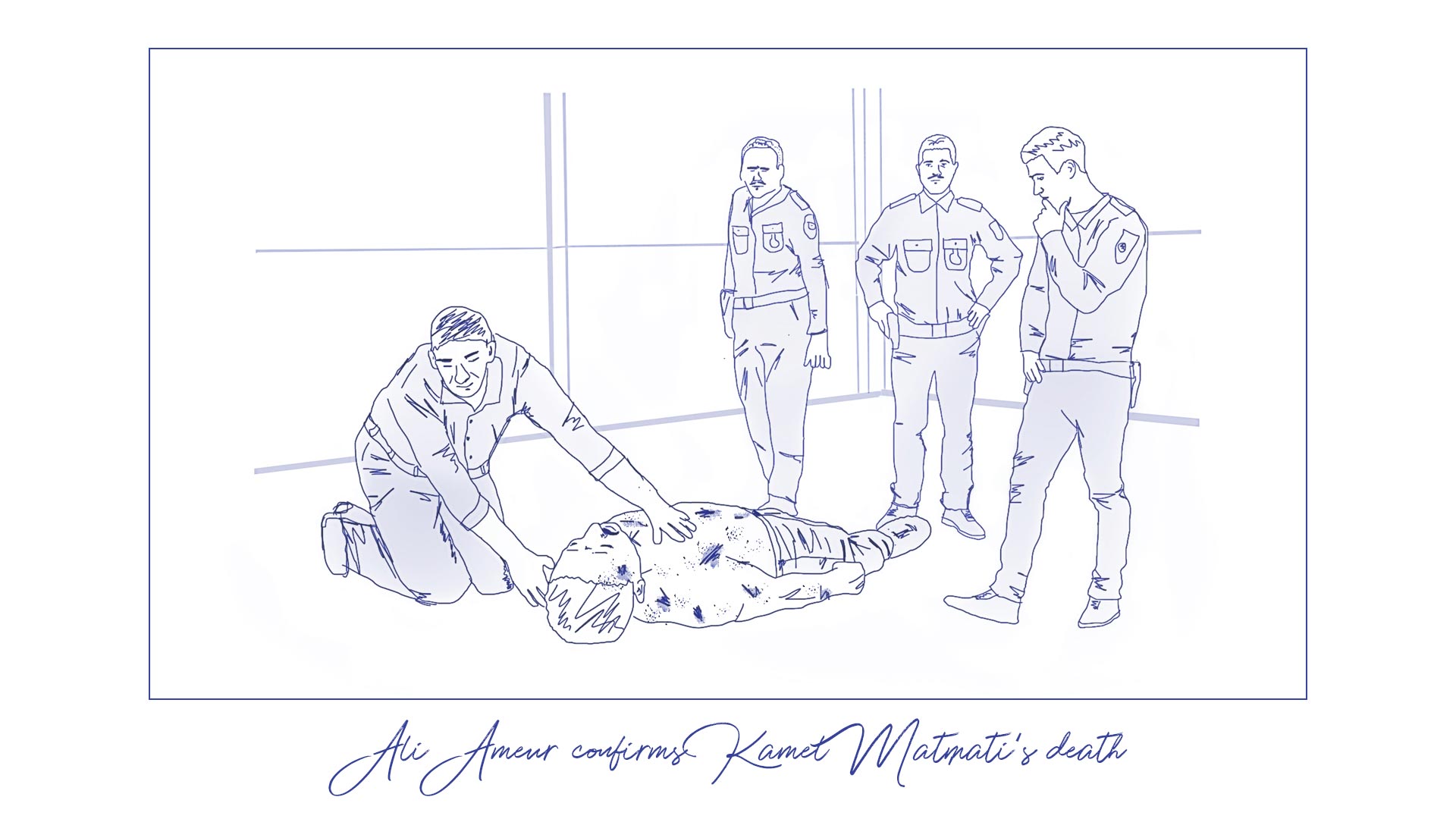

Proof of Death

Ali Ameur is once again called to assess the damage inflicted upon the body of the victim. “ I placed my ear on his heart.” After checking several times, the doctor stands up. “ He’s dead, he’s dead,” he says to the executioners.

The three policemen and the chief immediately take Kamel’s body and disappear. “ Mustapha, Riadh, and Anouar. They are the three policemen who, along with Ali Boussetta, tortured him,” says the doctor.

“ They came back after some time and one of them told us, ‘consider yourselves happy that your friend is dead. Tonight we will bring some beers and celebrate.’”

But Ali Ameur’s nightmare doesn’t end there. The day after Kamel Matmati’s death, he and the other detainees are forced to clean the cell of blood and excrement with strong chemicals. They are detained for another three months to prevent the news of Matmati’s death spreading.

Following a sham trial, Ali is condemned to almost 20 years in prison. He is eventually released in 1999. Weakened and traumatized, he never dares to tell Kamel Matmati’s family what happened on October 8th of 1991* in the Gabes police station.

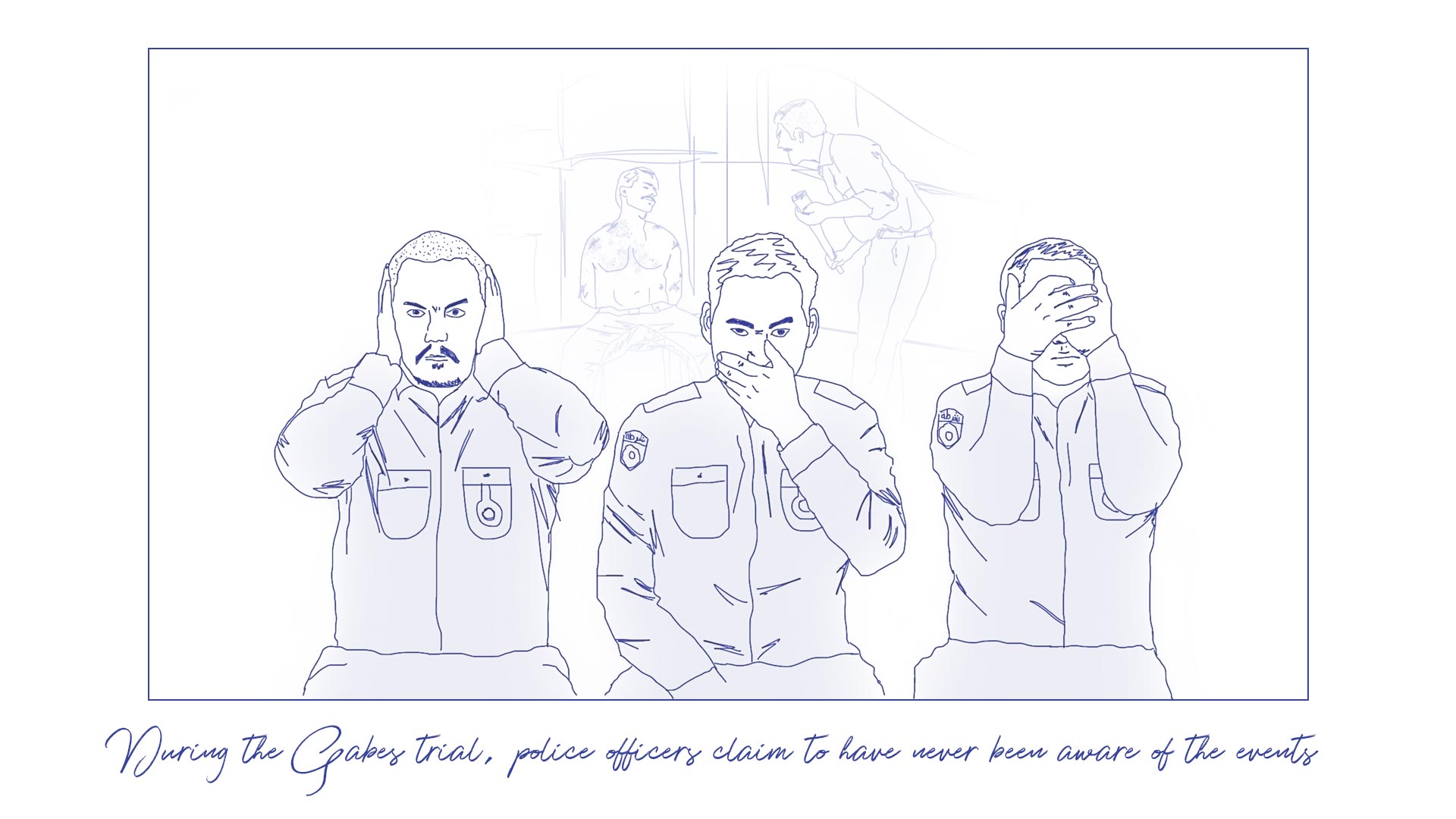

The code of silence

Khelifa worked with the special services unit in Gabes under the direction of Samir Zaâtouri. Khelifa’s role was to write up reports for his superiors, oftentimes about people applying for passports. “ You had to know if they belong to Ennahda,” he states to the judge from behind a protective screen.

Throughout the trial, Khelifa provides vague answers. “ I wasn’t present . . . I didn’t see anything . . . I just heard that there was some violence to make them talk . . . some punches . . . to make the truth come out.” Describing the violence perpetrated by the policemen, Khelifa refuses to use the word “torture,” which he considers an exaggeration. He assures that no orders were issued to torture prisoners.

After some hesitation, he finally admits to having heard his colleagues speak about Kamel Matmati: “ They said he was dead in their hands.” The day after the incident, he learned that the victim’s body was transported to the hospital of the interior security forces in La Marsa, a suburb of Tunis. “ I was shocked for three days,” Khelifa said, before naming some of the men involved. A short while before the incident, these men had been transferred from Tunis to Gabes in order to reinforce the new unit and to continue their training, all under the supervision of Ali Boussetta. Up until this point, Khelifa hadn’t told anyone about what he had learned. “ Samir Zaâtouri, our direct supervisor, was aware of the operation. What could I do?” he asks. “ In those days, we couldn’t inform anymore, and we needed to eat.”

During another testimony, skeptical laughter is heard in the courtroom. Mongi, another policeman on the stand, pretends not to know the infamous “poulet roti” torture technique even though he had cited it a few moments prior. “ After this episode, we ceased arrests, everyone was shocked,” he continues without reaction.

“ I was a simple police officer, I needed to earn a living and no information could come out. This was our work. We had to live.”

Despite the trivialization of violence and the little information divulged, the testimonies of the police officers painted a coherent picture of what happened that day. Ali Boussetta, chief of investigation, and three of his policemen were present in the cell where Kamel Matmati died. During the night, two other policemen from the same brigade transported his body to the hospital in La Marsa. Samir Zaâtouri supervised it all.

The file compiled by the IVD confirms this series of events. According to the report, Samir Zaâtouri informed Hassan Abid (chief of intelligence) of the death of Kamel Matmati. Hassan Abid then asked two policemen to take the body of the victim to the hospital of the interior security forces in La Marsa and to deliver it to Dr. Ahmed Ghattas. The body was transported during the night without any paper trail left to record the fate of the victim.

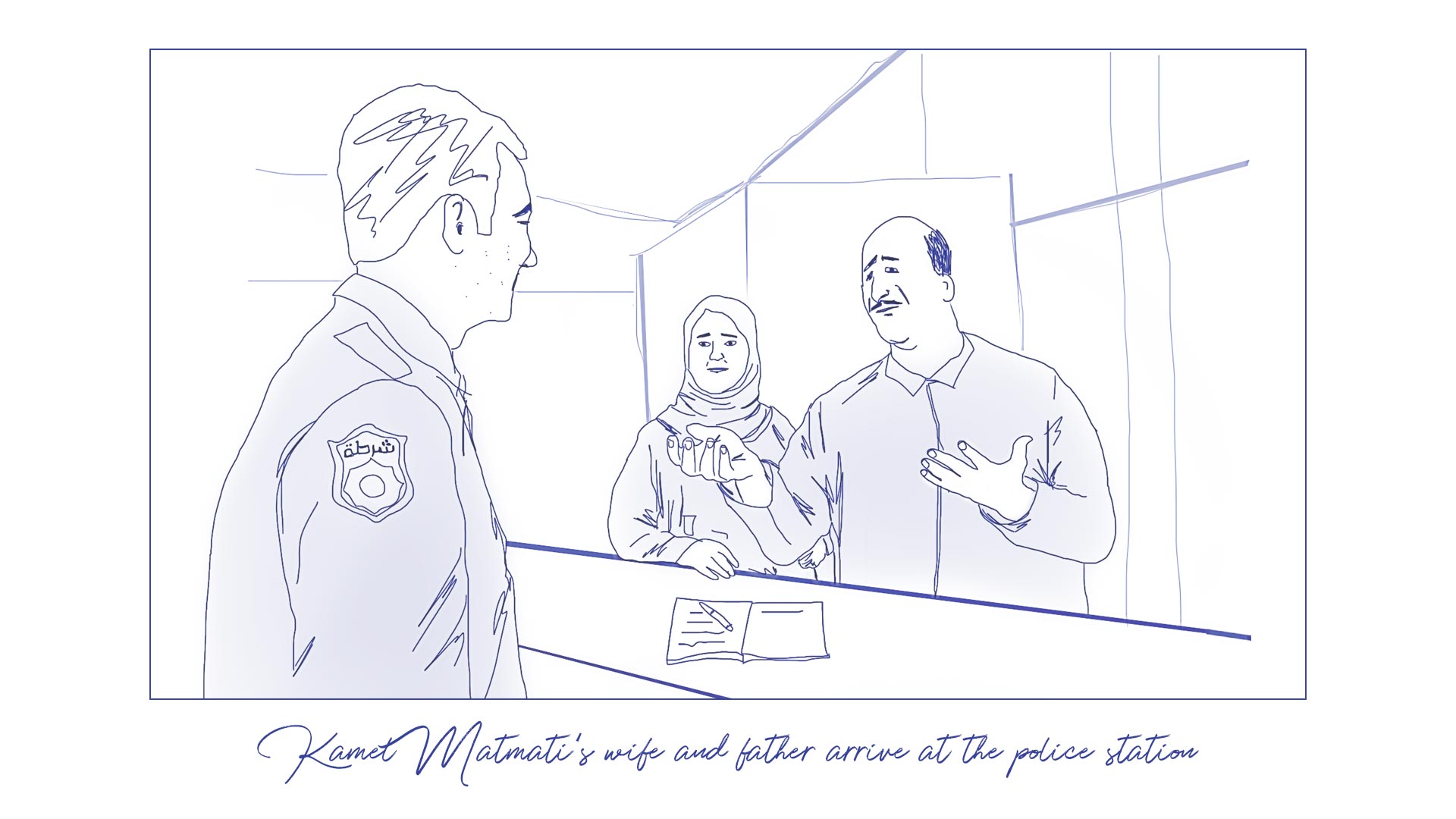

20 years in the dark

The day after the disappearance of her husband, Latifa Matmati and her father-in-law go to the police station. “ We came for Kamel,” she tells the policeman. “ He’s not here,” he responds.

She is able to get a glance at the open register lying on his desk. “ There is his name!” she exclaims. The policeman violently closes the register and asks them to leave.

Fatma, Kamel Matmati’s mother, had been staying with family members during this period. “ When there was a knock on the door, I knew that something had happened to Kamel,” she recalls, sobbing.

A while later, the police make the family believe that Kamel Matmati is still in detention. “ They asked me to bring him clothes,” says the victim’s wife. Afterwards, they ask that she bring him food. But the charade is short lived. Unworn clothes are eventually returned to the family, and their suspicions mount higher.

Trying to cover their tracks, the authorities claimed that Kamel Matmati was a wanted man and that his family was hiding him. The deceased victim was then prosecuted before Gabes’ criminal division of the court of appeals for crimes related to his affiliation with Ennahdha (the islamist movement). On May 20th, 1992, he was sentenced in absentia to 17 years and four months in prison plus another four years of probation.

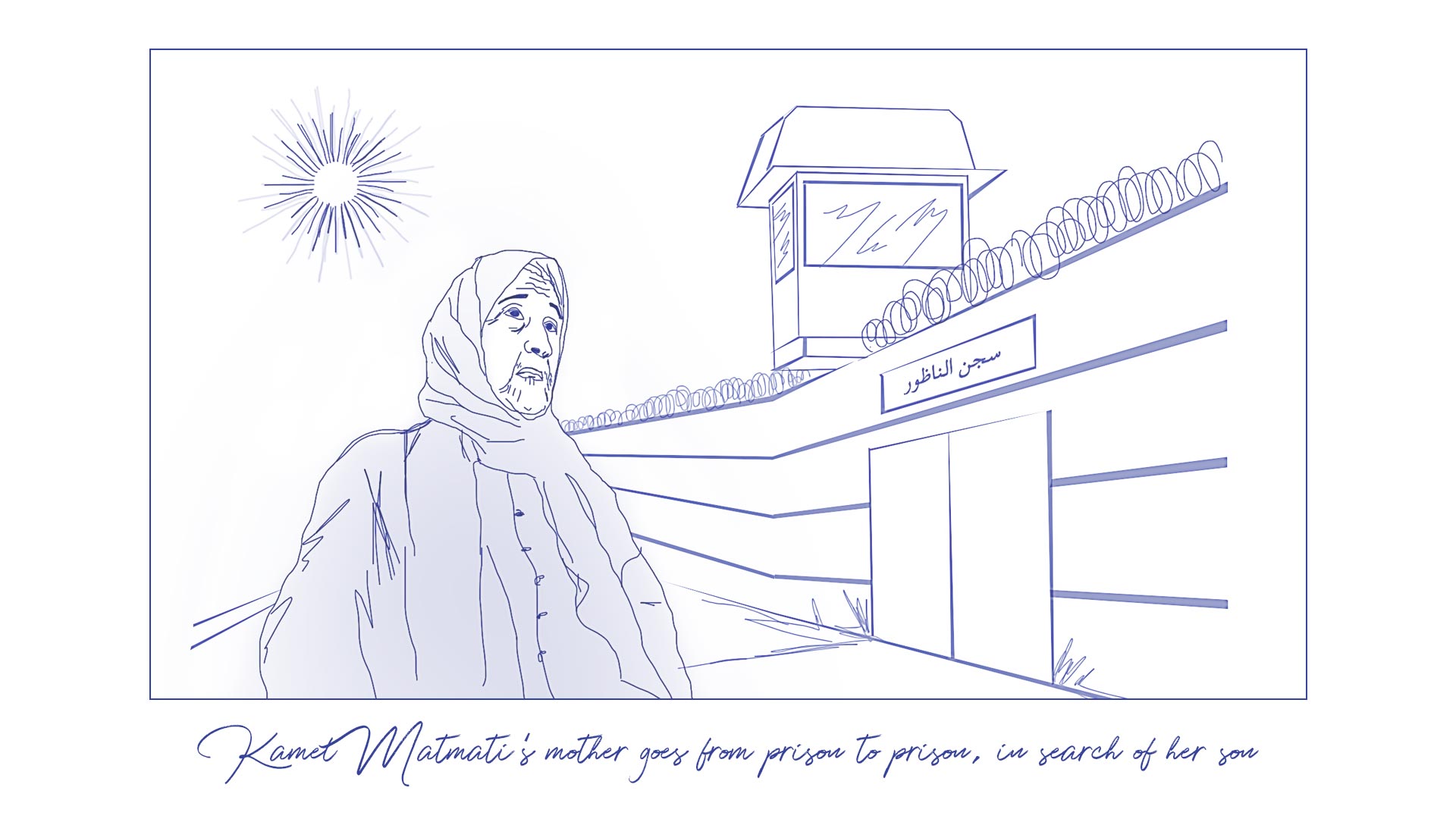

For years, Kamel Matmati’s mother goes from prison to prison in search of her son. But hope of finding her son slowly turns to disillusionment.

“ In the end, I went to the prison of Bizerte, I walked and I walked . . . there was no one but me. When I arrived, I fainted."

Latifa Matmati is also placed under administrative control, which forces her to report all of her movements to the police.

It is only after the revolution that the Tunisian state confirms the death of Kamel Matmati and issues a death certificate to the family. But since the crime took place over 20 year prior (exceeding the statute of limitations), the family is unable to file a complaint with the Gabes courts.

Conclusion

After the establishment of the transitional justice process, the IVD took on Kamel Matmati’s case. Fatma and Latifa Matmati testified during the first days of the public hearings.

The case was subsequently transferred to the IVD special chamber in Gabes and the trial was set for the end of May 2018. Due to a mistake while issuing the summons, none of the accused came to testify. However, several witnesses claimed to have seen Ali Boussetta in the courtroom.

Once again, during the second hearing held on July 10th, none of the accused were present, despite being formally summoned this time. Meanwhile, with no travel ban stopping him, Ali Boussetta fled to France. " His extradition would be complicated,” claims Mokhtar Jemai, lead counsel for the plaintiffs. The other defendants were finally placed under a travel ban, but remain free within Tunisian borders. The next hearing is scheduled for October 9th, 2018. In the meantime, Kamel Matmati’s remains are still missing.