Tunisians revealed

Mossack Fonseca works with intermediaries in countries around the world; Tunisia being one of them.

Among the Tunisians figured in the leaked documents are several lawyers acting on their own behalf or on behalf of a company. We also find government representatives, influential businessmen and public figures, as well as the owner of a major media outlet.

These actors are all connected to an offshore company, thereby joining the ranks of the global financial and political elites bending the law for tax evasion and capital gain.

In the coming days, Inkyfada will publish various investigations into how these Tunisian citizens joined the ranks of the global financial and political elites bending the law for tax evasion and capital gain.

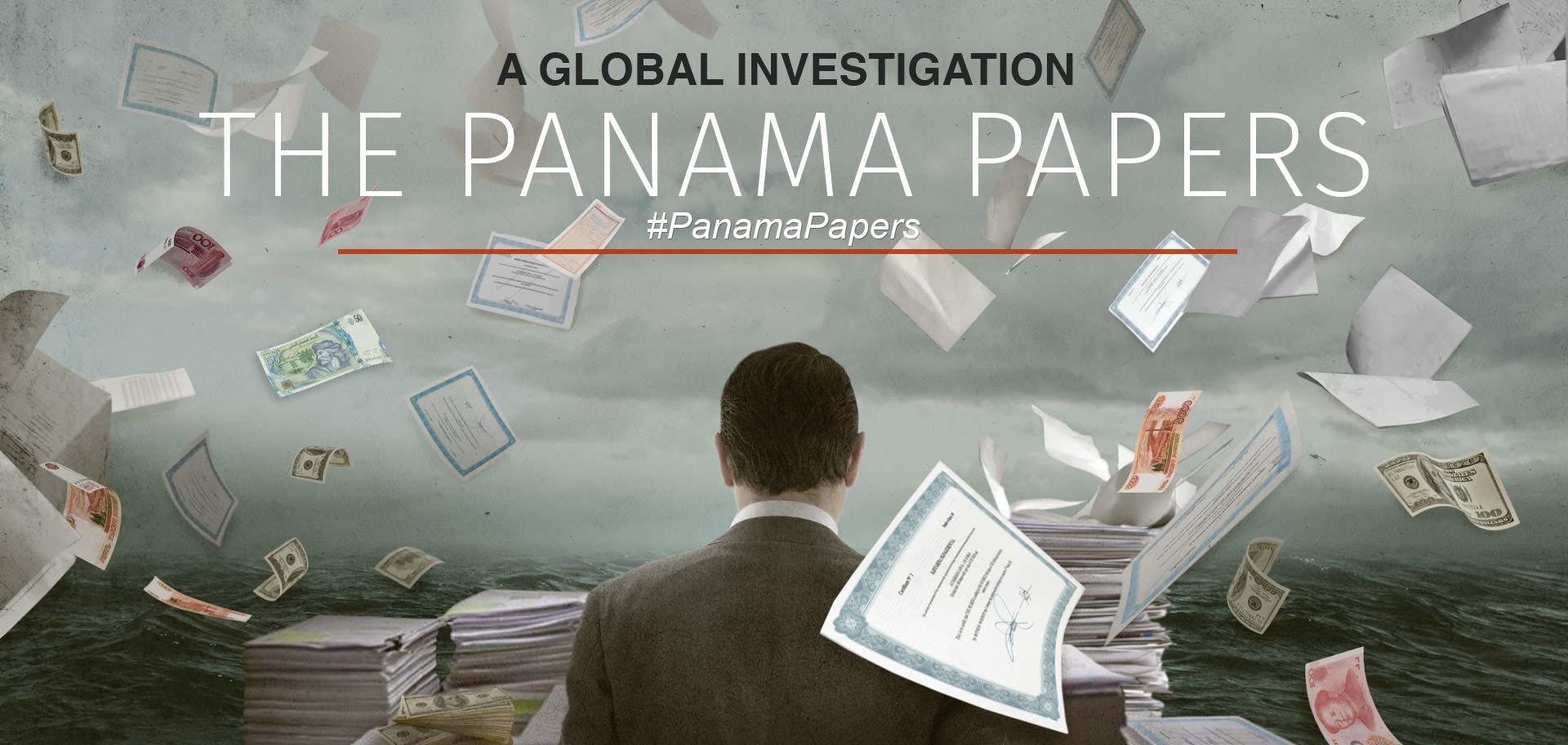

11.5 Million Documents Leaked

The International Consortium for Investigative Journalism (ICIJ) credits Süddeutsche Zeitung, one of Germany’s largest daily newspapers, for obtaining Mossack Fonseca’s internal documents. The two media partners then launched a global investigation, sharing sensitive information with hundreds of media outlets around the world. This information reveals, among many other processes, the various methods of opening offshore companies.

Inkyfada, as ICIJ's partner in Tunisia, received access to emails, meeting minutes, company incorporation certificates, copies of personal identity documents, and documents that detail the creation process for ‘extraterritorial companies,’ more commonly known as offshore companies.

The Panama Papers leak reveals 2.6 terabytes of data contained within 11.5 million documents produced between 1977 and 2015. The documents reveal the existence of 214,488 entities. These entities are established in 21 different jurisdictions: the British Virgin Islands, Panama, the Seychelles, Samoa, the Bahamas, Anguilla, Nevada, Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, Belize, Costa Rica, Wyoming, Malta, New Zealand, Cyprus, Niue, Uruguay, Ras Al Khaimah, Singapore, the Isle of Man, and Jersey.

There are 140 public figures included in the lists, including 12 heads of state — some still in office — and 128 politicians or political figures. Another 61 individuals in the lists are relatives or associates of heads of states.

Overall, 14,153 clients (including intermediaries) benefited from the services of Mossack Fonseca. 500 banks are implicated in helping to create more than 15,500 companies.

Over the course of one year, nearly 380 journalists examined this data, collaborating across 76 countries and representing more than 100 media outlets.

Mossack Fonseca and the Creation of Offshore Companies

At first glance, everything at Mossack Fonseca appears to be legal and regulated: it is a law firm specializing in legal advice and trusts and primarily assists intermediaries in creating companies. The firm’s communication clearly states that their services are comparable to consulting firms around the world.

But a further look into the firm’s paperwork reveals that the companies they helped to incorporate primarily reside in tax havens and that the owners of these companies are pushing, if not crossing, legal boundaries.

Mossack Fonseca’s response? The client is responsible, not the law office.

Mossack Fonseca was founded in 1977 by two lawyers: Jurgen Mossack — of German nationality — and Ramón Fonseca — of Panamanian nationality. In a March 2015 edition of Handelsblatt, a German economic newspaper, Mossack was declared the “German King of shell companies."

That same year, Brazil’s public prosecutor found that Mossack Fonseca was implicated in creating companies for the purpose of money laundering.

Earlier, in 2014, the North American site Vice Media published the article "Mossack Fonseca, the firm that works with oligarchs, money launderers, and dictators." This article explained how Rami Makhlouf, a member of Bashar al-Assad's family, had evaded millions of dollars via an offshore company registered in the Virgin Islands and formed with the help of Mossack Fonseca.

The ICIJ contacted Mossack Fonseca regarding the Panama Papers investigation. An email response from the company’s director of public relations, Carlos Sousa, explains that the firm provides services from registered agents to professional clients — lawyers, banks, and trusts, all of which act as intermediaries.

This information also appears in an email exchange between Mossack Fonseca and a potential Tunisian client who, lacking intermediary status, was directed to the company's other services.

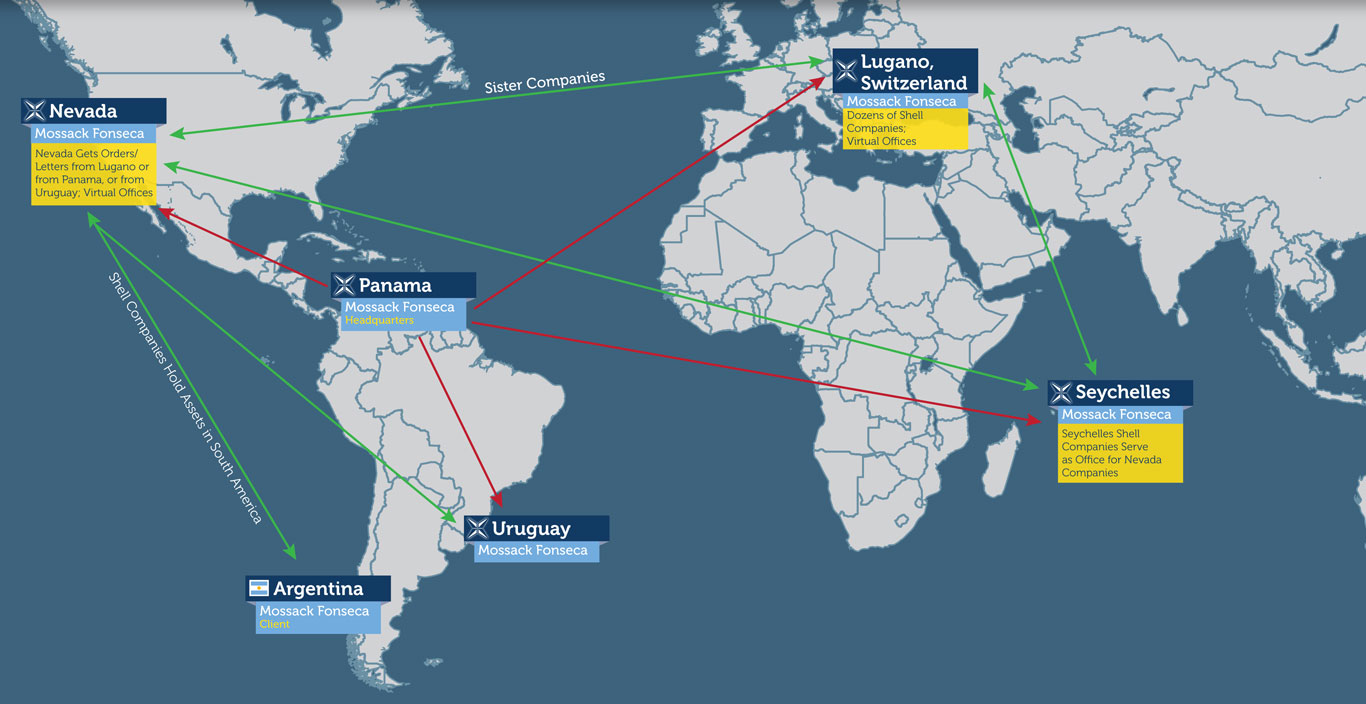

Map of Mossack Fonseca’s international branches

Sousa explains that before establishing a contract, “and before agreeing to work with a client,” Mossack Fonseca conducts a review [on the potential client]. However, offering to build a case for the creation of a business “is very different than creating a link or guiding the already established company.” Thus, Mossack Fonseca is absolved of all responsibility for a company’s actions once it has been established.

During his first exchange with the ICIJ, Sousa concludes by stating that in nearly 40 years of activity, Mossack Fonseca has never been convicted of a criminal act.

In a follow-up exchange with the ICIJ, Carlos Sousa goes over certain points in more detail. He says the law firm only offers legal services that comparable firms offer, and that these services are provided in compliance with regulations. He also says that beyond being asked about their activities, some potential clients are also asked about the origin of their funds. Mossack Fonseca carries out investigations into their clients and regrets any misuse of their services; they alert authorities of any suspicious activity. “Tax avoidance is not the same as tax evasion,” Sousa claims. In other words, Mossack Fonseca helps to optimize, not to defraud.

What is an offshore company?

Tax havens — whether sovereign states or dependent territories — are classified by strict banking secrecy, limited international oversight, little to no taxation on incomes, profits or assets (especially for non-residents), and processes for creating businesses that require little paperwork and accounting.

Mossack Fonseca highlighted these advantages to a potential client via two documents that compile the benefits of incorporating a company in either the British Virgin Islands or Anguilla.

For many years, offshore financial centers (i.e. tax havens) have specialized in servicing asset holders around the world such as multinational firms’ headquarters, pension and investment funds, and individuals who want to shield their assets from the tax institutions of their respective countries.

Although having an offshore company does not necessarily mean that one is evading taxes, it does offer asset holders a unique opacity through which to move funds.

Its structure thus lends itself to tax evasion and money laundering. Tax havens have also been known to funnel ‘dirty money’ from criminal or fraudulent activities back into circulation, often through the use of shell companies.

In many cases, companies created in tax havens only serve to process transactions on behalf of other companies or individuals. For example, a company or an individual based in a high-tax country can evade financial obligations by transferring their assets to a ‘shell’ company in a tax haven with little to no taxes. This constitutes tax evasion.

More broadly speaking, tax havens can also be defined as jurisdictions with legal systems that favor the inflow of capital from foreign countries.

To help you better understand tax havens, the ICIJ and Le Monde created a game, Stairway to Tax Heaven, in which your goal is to navigate the secret world of offshore and hide away your cash.

According to Tunisian law

It is legal for a Tunisian citizen to open an offshore company. According to the Tunisian Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Code, the owner of an offshore company is required to declare with the Central Bank.

Article 16

All Tunisians who habitually reside in Tunisia, all Tunisian legal persons, as well as foreign legal persons who are established in Tunisia, are obliged to declare their foreign assets with the Tunisian Central Bank within a period of six months from the promulgation of this law and must declare all new acquisitions made after the promulgation of the law.

In the case that the value of the assets does not exceed the amount stipulated in the decree, the owner is exempt from declaring them.

The declaration has to be made either by the owner of the assets or by a person in Tunisia who is mandated with management on behalf of the owner. These persons are jointly liable for the execution of this obligation.

Owners of assets held abroad on their behalf by authorized intermediaries in Tunisia are not required to declare them.

All Tunisians who habitually reside in Tunisia, all Tunisian legal persons, as well as foreign legal persons who are established in Tunisia, are obliged to declare their foreign assets with the Tunisian Central Bank within a period of six months from the promulgation of this law and must declare all new acquisitions made after the promulgation of the law.

In the case that the value of the assets does not exceed the amount stipulated in the decree, the owner is exempt from declaring them. The declaration has to be made either by the owner of the assets or by a person in Tunisia who is mandated with management on behalf of the owner. These persons are jointly liable for the execution of this obligation. Owners of assets held abroad on their behalf by authorized intermediaries in Tunisia are not required to declare them.

The Code puts forth a broad definition of assets: gold, means of payment, securities, but also "all property, rights and interests abroad represented or not by securities." Shares held in companies established abroad are therefore included in the definition.

More than a handful of Tunisians figured among the Panama Paper documents made available to Inkyfada. According to these documents, most of these individuals were residing in Tunisia during their exchanges with Mossack Fonseca.

Mossack Fonseca is not the only law firm of its type working with Tunisian citizens. One Tunisian business lawyer told us he had been contacted by Maltese consulting firms aiming to sell their services.

"They offered to help my clients set up offshore businesses with attractive tax benefits...taxation that does not exceed 3% and residency in a European country as a bonus."

As we can now see through the leaked documents from Mossack Fonseca, creating an offshore company, via an intermediary, lawyer, or bank, is not out of reach for Tunisian citizens.