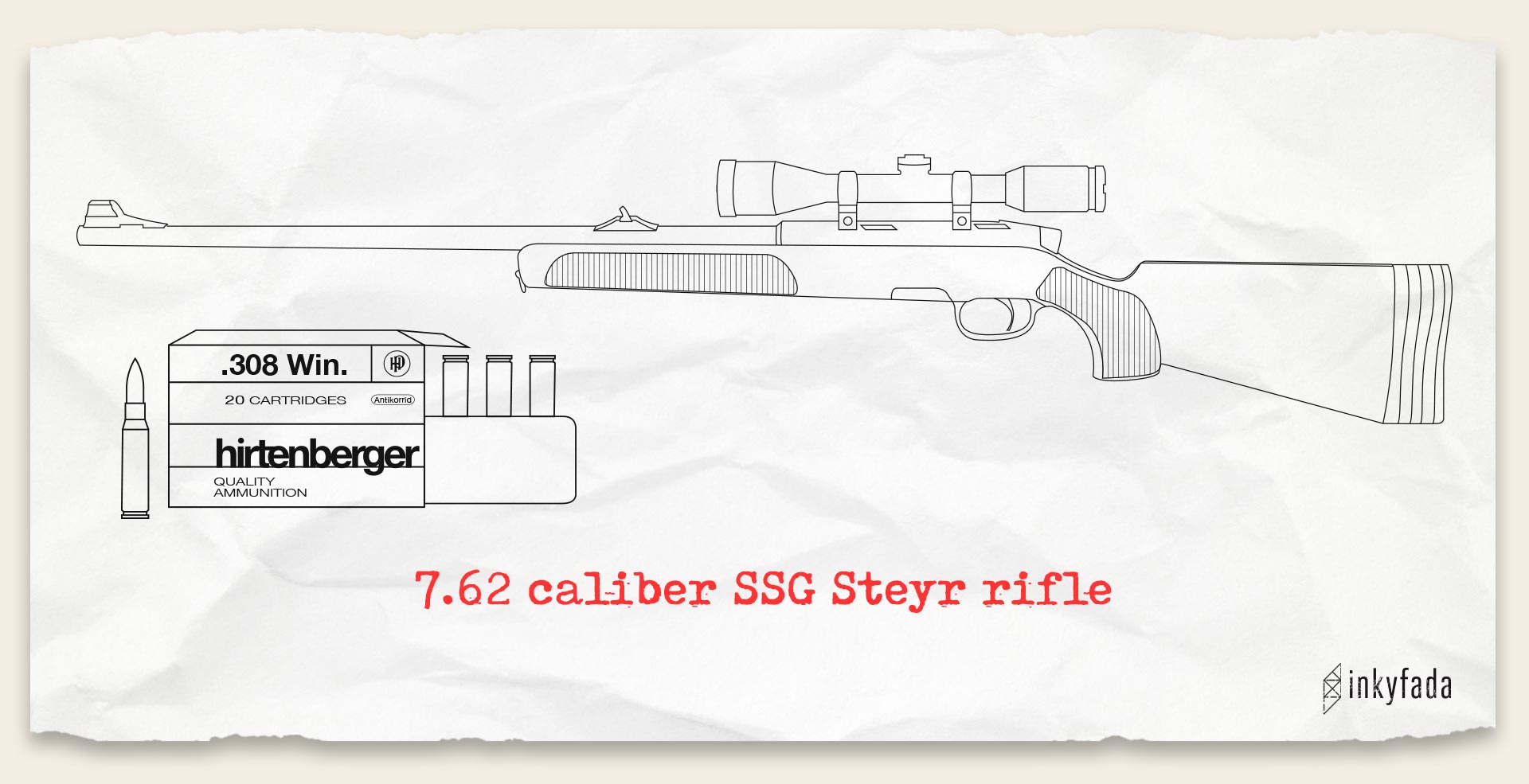

In this case, the victim was a sergeant at the Department of Prisons and Rehabilitation. He was killed on January 17, 2011, right after Ben Ali’s departure. During this chaotic time, there was widespread talk of snipers targeting civilians. More specifically, murders and injuries that had been committed by 7.62 mm bullets were being reported. Yet, at the time, the entirety of the Tunisian armed forces denied being in possession of any ammunition of this caliber. This triggered a wide range of interpretations as to who could be in possession of this type of bullet, and who would have an interest in targeting civilians.

Uncertainty gave way to rumors, leading some Tunisians to believe that terrorists coming down from the mountains had infiltrated the demonstrations and killed demonstrators with 7.62 mm bullets before vanishing. This hypothesis was presented by Ali Seriati (former Director of Presidential Security), during his trial following the revolution. This view was further echoed by a number of security officials within the Ministry of the Interior, and by some of Ben Ali's relatives (such as his brother-in-law, Slim Chiboub), during a televised interview.

Béji Caïd Essebsi (President of the Republic and Head of the Transitional Government at the time), attempted to close the file by categorically denying the existence of snipers, with a phrase that is widely remembered: " Whoever finds a sniper, let them bring him to me."

However, the case of Amine Grami challenged all the pre-existing hypotheses by proving that at least one part of theTunisian armed forces (namely the National Army), used this type of ammunition during the revolution.

So, what exactly happened that day? How and why did the military justice system grant freedom to the accused, when there was ample evidence supporting a conviction for premeditated murder?

THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF AMINE GRAMI’S MURDER

On January 17, 2011, prison officer Amine Grami was standing guard at the regional hospital of Bizerte, more precisely in Room N° 07 located on the sixth floor. He was guarding resident prisoners who had been transferred there to receive treatment for injuries and burns sustained during the mutiny at the Borj Erroumi prison, a mutiny that had coincided with Ben Ali's departure.

When Grami heard gunshots accompanied by the sound of a helicopter flying over the hospital, he approached the window facing the Technical School of the Army, to see what was going on. This was when he was shot in the head.

" We heard intense gunfire coming from the national army barracks near the hospital - and around noon, while I was in the room with some colleagues, my late colleague Amine Grami walked towards the window. Just as we approached, he was hit by a bullet above his left ear and dropped to the floor. We crawled towards him to avoid the continuing gunfire that was moving towards the adjacent room. We found him lifeless." - Excerpt from the witness testimony of Sergeant Khaled Ryabi, the victim's colleague and the previous head of the Second Central Unit of the National Guard in Aouina.

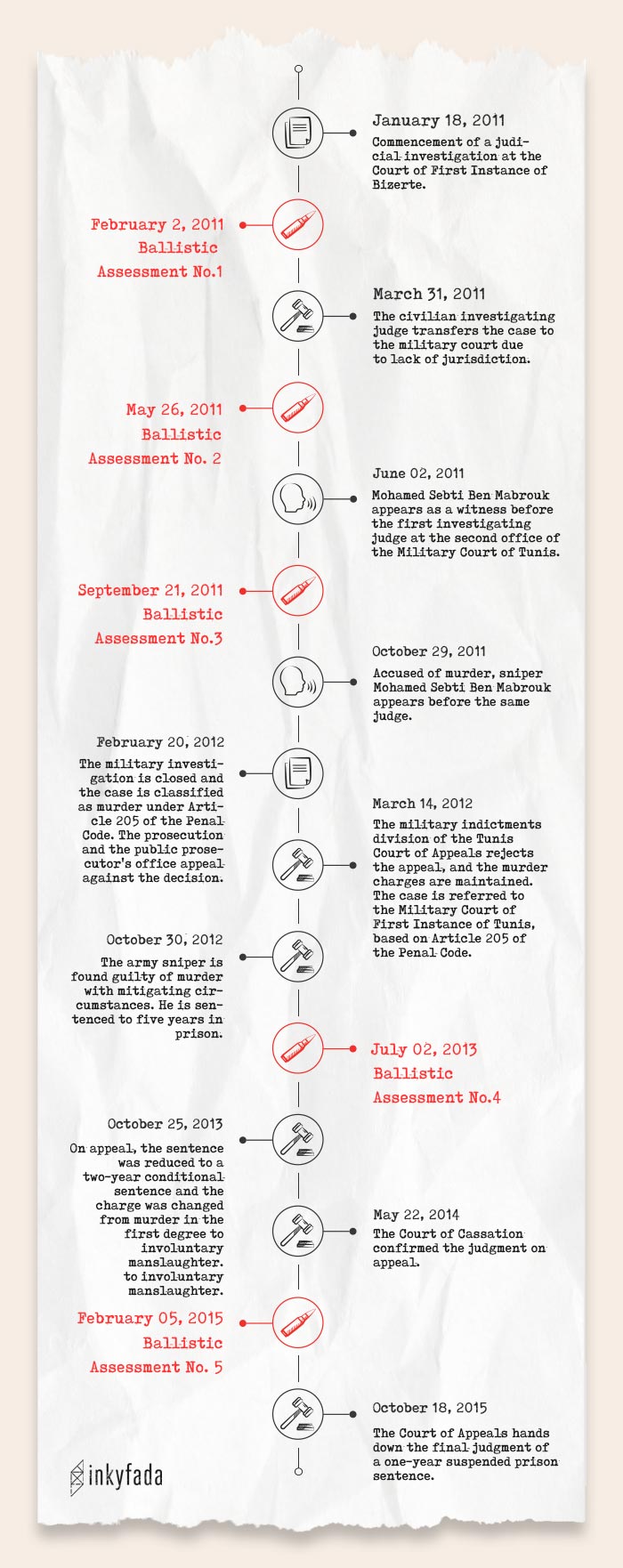

The very next day, Grami's father filed a criminal complaint with the Court of First Instance of Bizerte, which was brought before the public prosecutor's office on the same day, requesting the opening of an investigation "to determine the causes of death of the deceased." The investigating judge at the Third Office of the Court of First Instance of Bizerte, Imed Boukhris, and succeeded in deciphering certain elements of the crime before dropping the case in favor of the military justice system.

CIVIL JUSTICE: AN ELITE ARMY SNIPER IN THE DEFENDANT’S DOCK

Civil investigating judge Imed Boukhris opened his investigation with a series of requisitions and rogatory letters, in order for Dr. Anis Ben Khelifa to carry out the autopsy, and for the Second Central Unit of the National Guard in Aouina to investigate anything that might shed further light on the case.

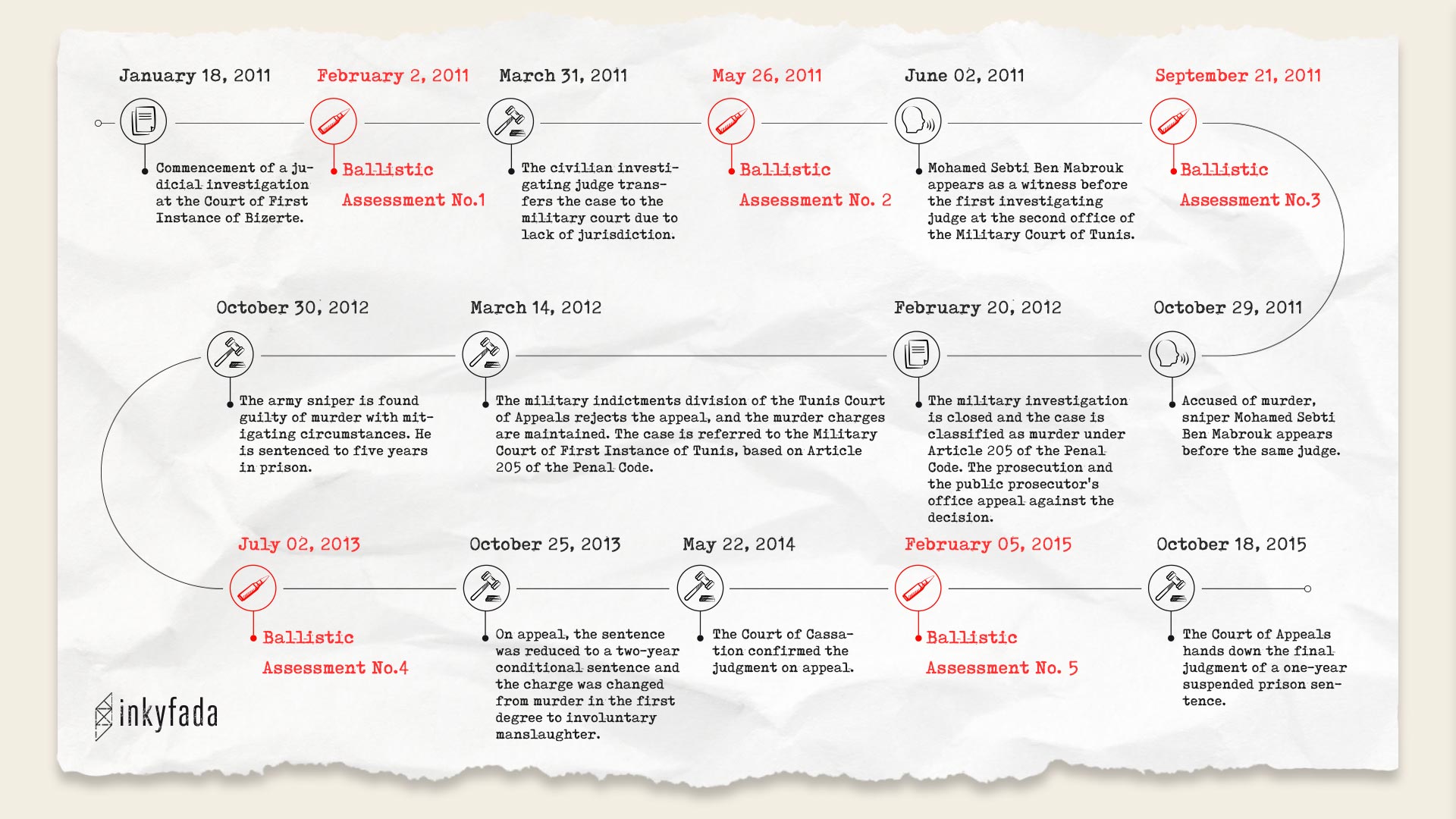

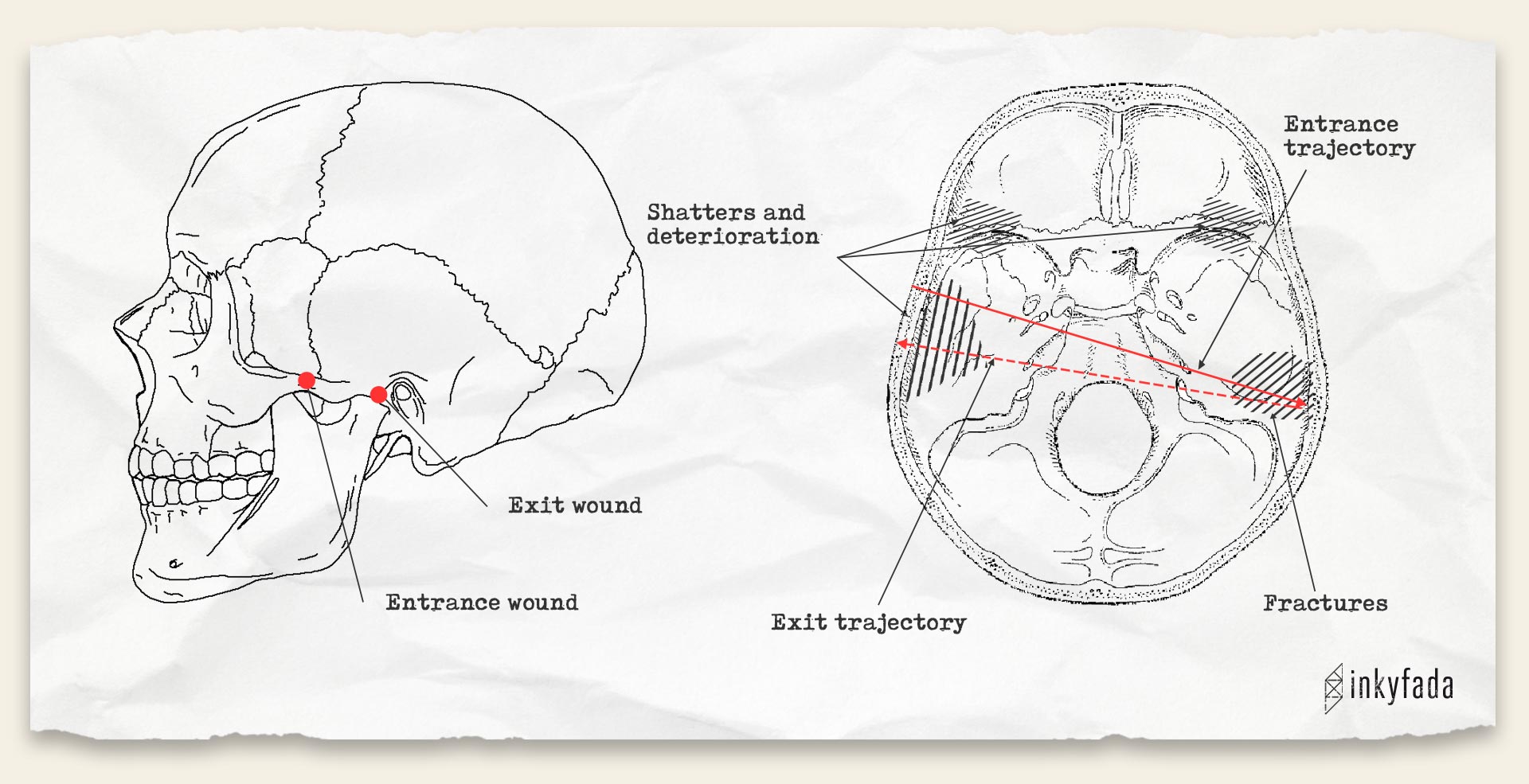

The autopsy report established that the death was caused by a ' traumatic brain injury'. The bullet's entry and exit points being on the same (left) side of the skull (instead of being on opposite sides), was explained by the fact that the bullet, entering above the left ear, had ricocheted inside the skull on the right side of the head and fractured, creating a second exit hole close to the entry point on the left side.

Explanatory diagram showing the trajectory of the bullet that struck prison officer Amine Grami (data taken from the report of the forensic doctor, Dr Anis ben Khelifa).

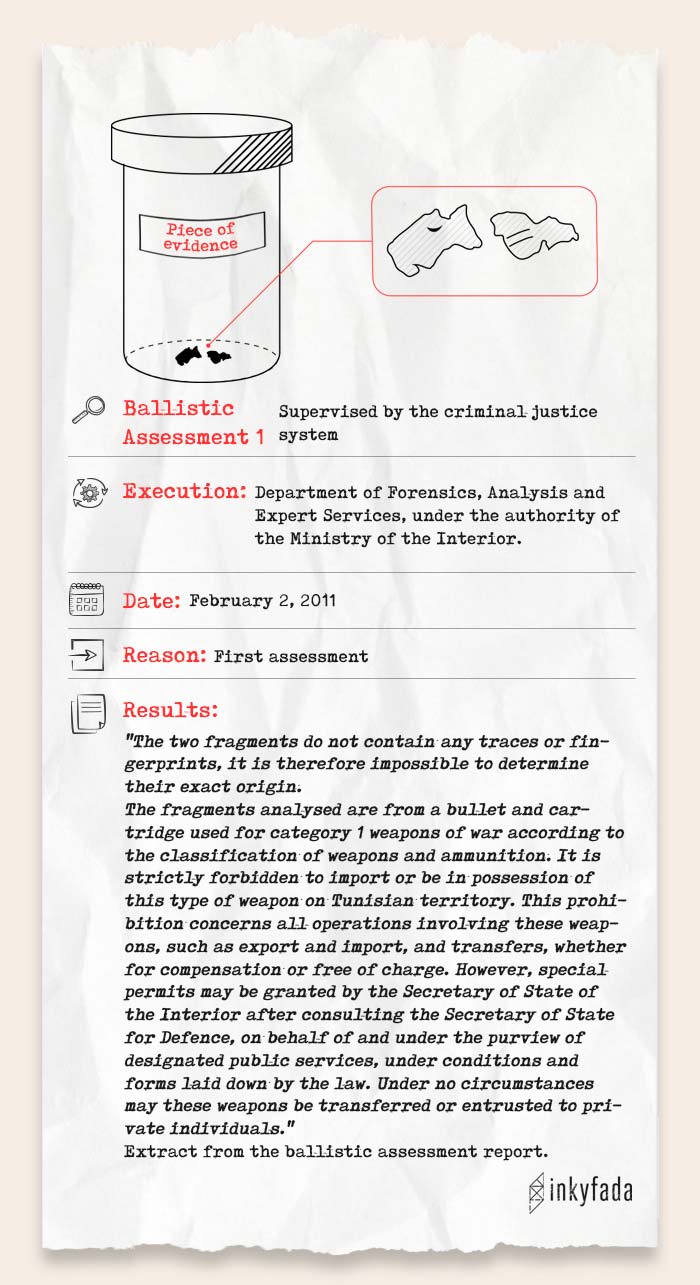

The forensic report concluded that the death was caused by a fatal gunshot wound to the left ear, fired with great accuracy from a single shot weapon. The medical examiner also managed to extract two bullet fragments lodged in the head of the deceased. The investigating judge then sent the fragments for analysis to the analysis and testing service of the Police Department of Forensics.

After examining the two fragments, it was revealed that they belonged to a first-class cartridge, according to the official classification of weapons and ammunition.

Upon hearing the testimonies of several witnesses, including the victim's colleagues who had been present with him that day, the Second Central Unit of the National Guard in Aouina also made significant progress in their research. The results were then reported to the investigating judge so that he could proceed with an inspection of the crime scene, with the aim of finding the source of the fatal bullet in Room N° 07.

At the same time, the investigation also examined the trajectory of a second bullet that had wounded another hospital patient on the same floor in Room N° 04, before hitting the wall. No fragments or remains of this bullet were found.

At the hospital, the judge used what is known as reverse lens technology. This method consists of directing the lens of a reversed camera onto the spot where the bullet hit the victim's finger (M.S.Z.) in Room N° 04, as well as onto the place of fatality in Room N° 07. The camera then provides an image of the source of each of these bullets. This process established that both of the bullets shared the same source, namely the rear of the Technical School of the Army.

" What is revealed from the testimonies, the forensic report, and the test results from the two fragments extracted from the head of the deceased and the limited range of the shots (taking into account the physical barriers mentioned in the orientation and inspection report), is that the bullet that struck the deceased Mohamed Amine Grami was fired by a soldier located at the Technical School of the Army in Bizerte." Investigating Judge Imed Boukhris/ Sealing of the decision to dismiss.

After proving the military identity of the perpetrator, the civilian judge dismissed the case on March 31, 2011 on grounds of lack of civil jurisdiction. This was done in accordance with Article 52 of the Criminal Procedure Code and paragraph 6 of Article 5 of the Military Justice Code, which states that " military courts have jurisdiction over ordinary offences committed by or against military personnel during or in connection to being on duty, as well as ordinary offences committed by military personnel among themselves outside of duty."

FROM CIVIL- TO MILITARY- JUSTICE

Despite the clarity of the conclusions provided by the civilian investigating judge during the investigation, the case became increasingly complex when it was taken on by the investigating judge at the Second Office of the Permanent Military Court. What had at first seemed obvious would later become a case of inextricable connections.

Throughout the trial, the defendant's stories multiplied. However, to support his case, he consistently claimed to have used a total of five bullets that day, only one of which was aimed at a window frame of the hospital.

During his testimony as a witness, Lieutenant Sofiene Hani (a colleague of the defendant), stated that while he was " with the Chief Warrant Officer at their guardhouse, behind a window in the corridor of the boarding school, they saw a group of men regularly glancing through the opposite window, located on the sixth and top floor of the hospital. It was at this point that Sergeant Mohamed Sebti Mabrouk pointed his weapon at this window and fired, thinking that the group behind the window was made up of unknown and armed individuals."

During his hearing, the accused admitted to aiming (and shooting) towards the upper frame of the wooden window, in order to intimidate " one of the armed men who was pointing his head out of the window." However, according to the investigation file and the testimonies of many hospital employees working on that day, the prison officers were searched and stripped of their weapons at entry to the hospital by agents of the National Army who were in charge of guarding the premises.

The accused also claimed that he had only fired towards the window of Room N° 04 (and not N° 07). Yet, the civil investigating judge had already proven that the two bullets, the first fatal and the second wounding a hospital resident, originated from the same place: the second floor of the Khawarizmi Technical (boarding) School of the Army, where the accused sniper had been located. It was also confirmed by both judges, civil and military, that there were no bullet marks on the window frames of Room N° 07.

As for the other four bullets, the accused stated during the hearing on Thursday, January 17, 2013 for the first time that he " heard and saw persons in plain clothes firing shots from all sides towards the barracks." He therefore asked all those with him not to react, and to allow him to intervene. According to his statement, he used his weapon in the direction of El Qahwa El Allia café in the square. He further claimed to have chosen to aim at the wall in order to not harm anyone. He also added that " about three or four [plain-clothed gunmen] were arrested next to the barracks, and handed over to the Dean [of the Technical School of the Army at the time]."

However, the court paid no attention to the statements above, nor to what was said by the defendant about the group of armed men targeting the barracks and how they were arrested that day. Instead, the court requested another ballistic assessment, further complicating the case. After many twists and turns, the results of this test paved the way for the potential acquittal of the accused.

PROVEN GUILTY: THE DEFENDANT faces FIVE YEARS IN PRISON

On October 30, 2012, in the presence of the defendant, the Criminal Chamber of the Permanent Military Court of First Instance of Tunis announced that they found the defendant guilty, sentencing him to five years in prison.

However, there were certain inadequacies in handling the case. For example, the case file stated that on the day of the incident, the military command had requested a military helicopter for backup. This aircraft reportedly opened fire, targeting armed men on the rooftops of some buildings in front of the hospital. In light of this information, the defence counsel for the accused together with the prosecution agreed to request an investigation of the helicopter crew. On two separate occasions, the court asked the relevant military authorities for information about the crew and the types of weapons they were in possession of at the time of the incident. These inquiries remained unanswered.

In contrast, the Military Court of First Instance of Tunis stated in the explanatory note to the verdict that " the court does not consider the request to ‘ specify the names of all persons in possession of a weapon present at the scene of the incident’ to be relevant." The report of the commander of Khawarizmi School was considered satisfactory, even though it did not contain any information on the aircraft crew or the weapons and ammunition that were in their possession.

Despite the lack of evidence in the case file regarding the presence of armed men, and with no evidence of shots fired at the military school, the court affirmed the need to take into account the personal background of the accused, " who was performing his military duty, has a clean record and is known for his good conduct [...], in addition to the objective circumstances related to the presence of unidentified persons firing at the military forces present at the scene."

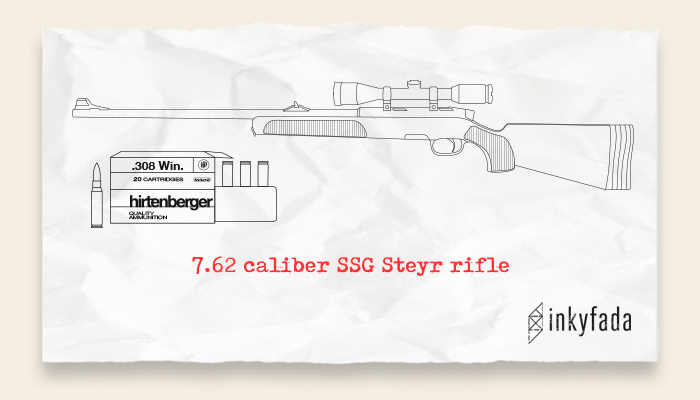

Within the verdict, the court additionally confirmed the ability of the accused to use his sniper rifle, despite it being a weapon " that makes it difficult to identify the target, and control its range and strike." According to the verdict, " there is no doubt that the acts committed by the accused were extremely dangerous, as they were committed by a soldier aware of the characteristics and seriousness of the weapon that he is using."

Hence, for the Criminal Chamber of the Permanent Military Court of First Instance of Tunis, it was proven that the death of Amine Grami was the direct result of the defendant's intention to shoot him. The court also confirmed that the testimonies of his colleagues who were with him that day were used against him to reach the verdict.

FROM PREMEDITATED MURDER TO INVOLUNTARY MANSLAUGHTER

However, the case was about to take a new turn.

Despite being convicted for premeditated murder and being sentences to five years in prison, the accused remained at liberty and continued to work for the military. In addition, even though most stages of the trial were (in theory) open to the public, most of the sessions were in fact held behind closed doors. The victim's family, the press, and some international organisations were repeatedly prevented from attending key hearings. The reasons for the secrecy surrounding the case remained unknown, leading to several complaints from the victim’s family and the defence.

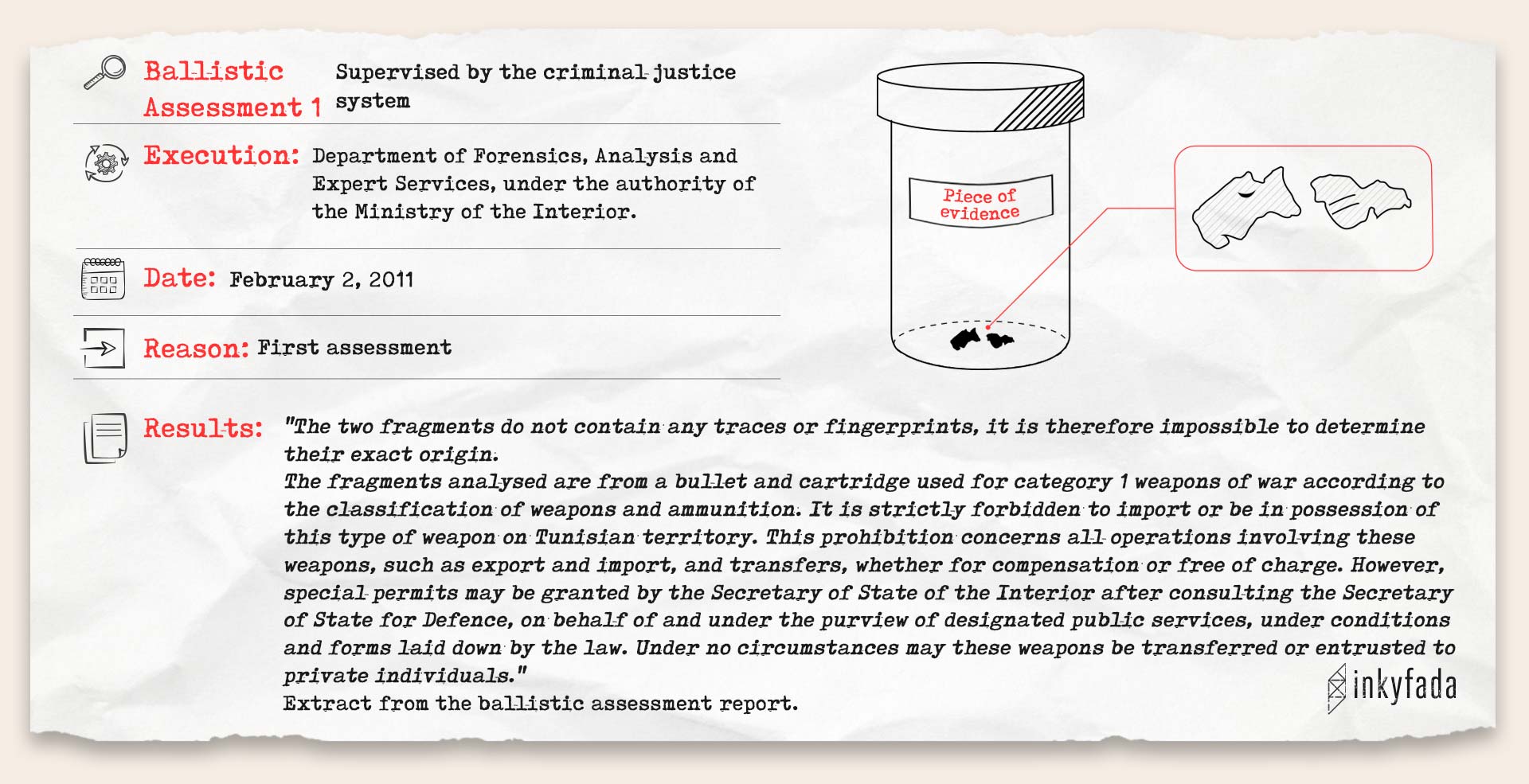

During the course of the appeal, faced with the defendant's various accounts and persistent refusal to acknowledge the allegations against him, and in the absence of clear evidence to either exonerate or convict him, the court decided to launch a series of ballistic assessments on the two remaining fragments of the fatal bullet. Through a series of explanatory illustrations, Inkyfada explains the distinctions and conclusions of each of these assessments, and further highlights the many questions that arise from the nature of the assessments, the reasoning behind them and the subsequent results.

The nature of these ballistic assessments, the reasons for conducting them and the results they yielded give rise to many questions.

The first assessment, supervised by the civil justice system, recognised that the bullet was of military caliber, exactly the same as the one used in the defendant's weapon. This was further confirmed by the forensic report that pointed to the source of the bullet being a highly precise weapon, like the one used by the defendant. Finally, the investigation of the civil judge had shown that the source of the shot was " a soldier on duty at the Technical School of the Army of Bizerte", i.e. the same position as that of the defendant at the time.

However, the findings of the tests that were supervised by the military justice system were neither coherent with previous assessments, nor with the new ones, which led to a major turning point in the case.

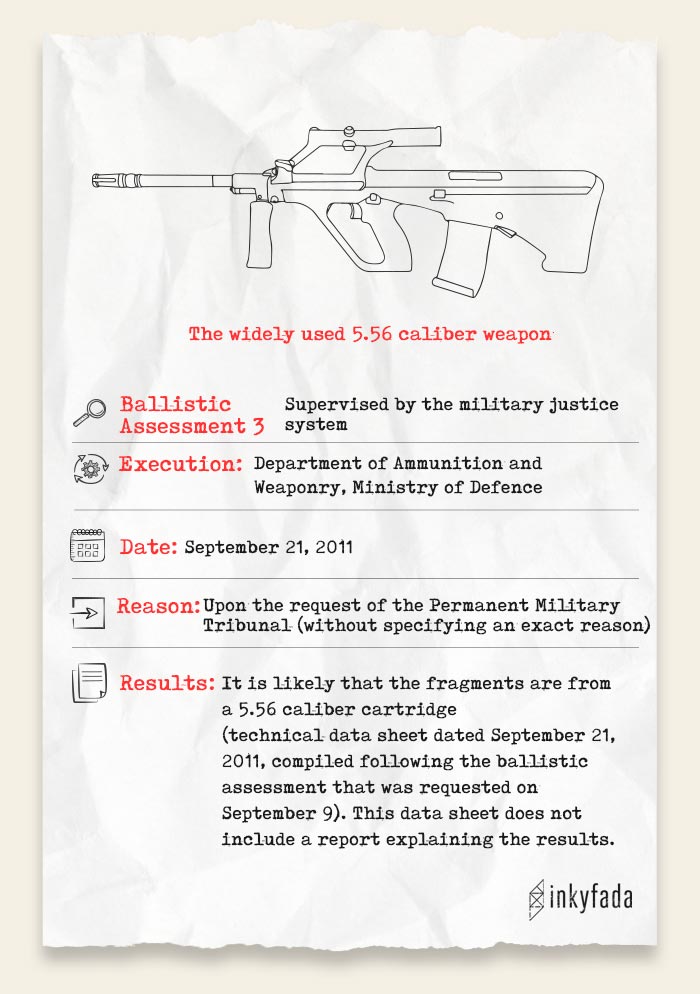

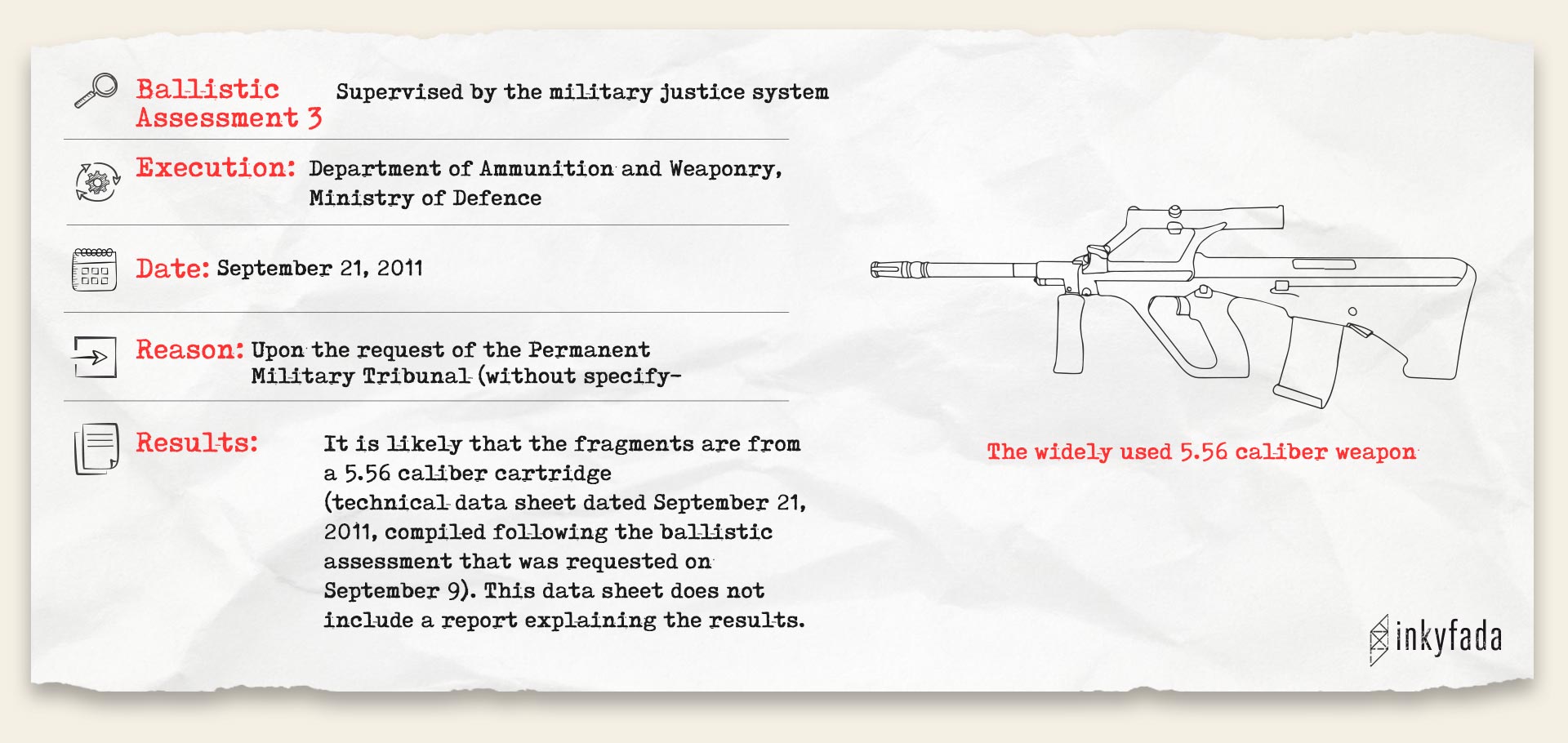

The assessment carried out by the Department of Ammunition and Weaponry at the Ministry of Defence on September 21, 2011 produced different results from the one carried out by the laboratories of the Ministry of the Interior on February 2, 2011. Meanwhile, the latter stated that the two fragments had no marks or spiral grooves (mechanical imprints) on their surfaces, making it impossible to determine the caliber of the bullet in question. The test by the Ministry of Defence claimed probability that the fragments were part of the casing of a 5.56 mm bullet.

It is important to note, however, that the control sheet of the assessment was not accompanied by any explanatory report pertaining to these results. Furthermore these results were not even mentioned in the text of the court verdict.

The reasons that prompted the military court to ask the Department of Ammunition and Weaponry of the Ministry of Defence to carry out further technical testing on bullet fragments in September 2011 remain puzzling. According to confidential correspondence from the Department of Ammunition and Weaponry, the court had been aware since May 2011 that " due to the small size of the bullet fragments, the type of cartridge, the source, and weapon used cannot be determined."

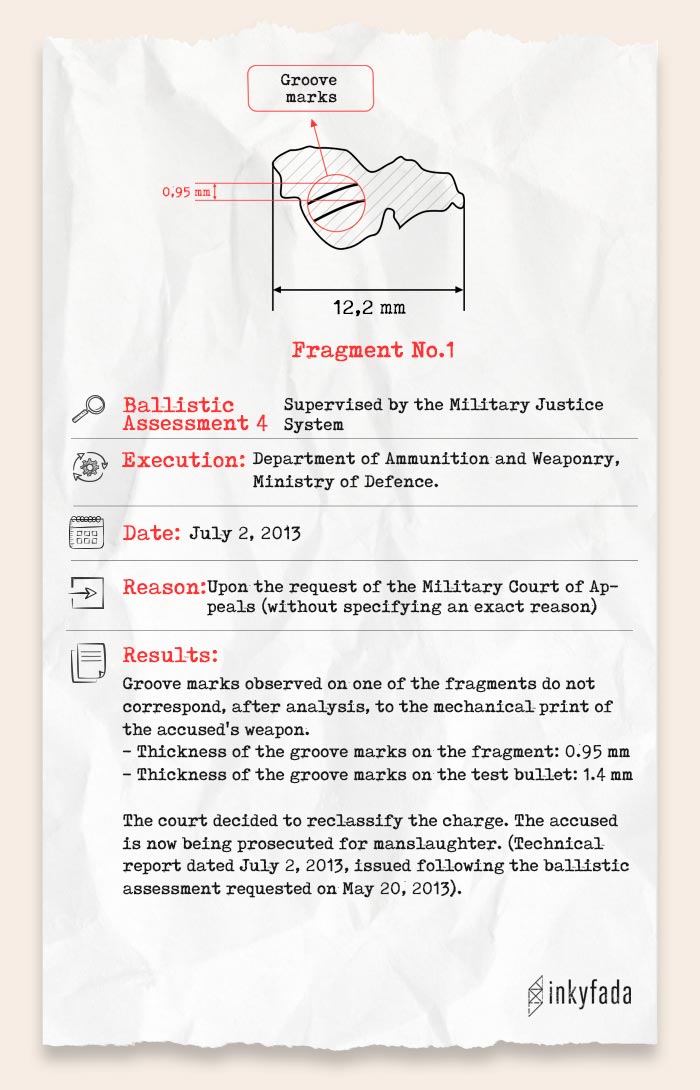

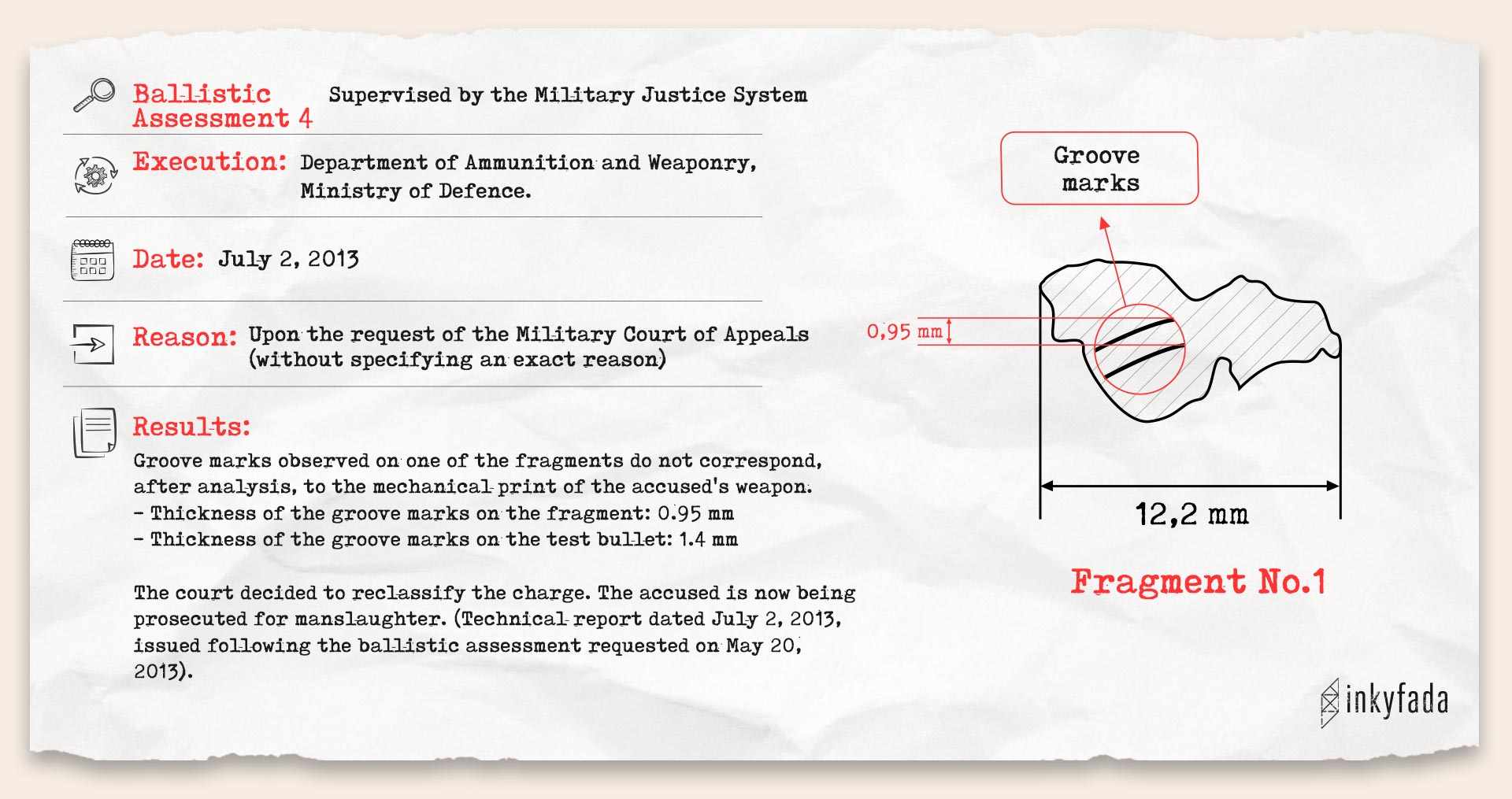

Curiously, despite prior knowledge (from the test carried out by the Ministry of the Interior and confidential correspondence) of the impossibility of determining the caliber of the bullet used, the Military Court of Appeals proceeded to carry out a fourth assessment on the bullet splinters. Strangely enough, the results of this assessment were different from all the previous ones; it not only revealed scratches on the bullet splinters, but also recognised that it belonged to a bullet of an unknown type, that could not have come from the defendant's weapon (7.62 mm).

The fourth ballistic assessment report indicated that the fragments of the bullet extracted from the victim's body were shredded casing pieces of an ordinary bullet from a small-caliber cartridge, and that the barrel of the SSG 7.62 sniper rifle could not have caused the scratches.

The report also estimated the distance between the defendant and the deceased at 130 meters, and set an angle of 15 degrees. It further concluded that the bullet that hit the deceased was fired from a distance of more than 200 meters, along a semi-horizontal line, at an almost non-existent angle. This was partly based on the idea that: had the deceased been hit from a distance of 130 metres and from a 15 degree firing angle, the exit hole of the bullet would inevitably be on the opposite side of the entry hole, and not on the same side as in the case of this victim.

THE CASE TAKES ANOTHER STRANGE TURN

The result of the last assessment (if approved) would have been sufficient to acquit the accused. Yet, on October 25, 2013, the court decided to reclassify the acts attributed to the accused as ‘manslaughter’ and issued an appeal verdict, sentencing him to a two-year suspended prison sentence.

This decision was contested by all parties involved, and overturned by the Court of Cassation. On May 22, 2014, it was decided to refer the case back to the Court of Appeals for reconsideration in a different circuit from the one that had handed down the verdict.

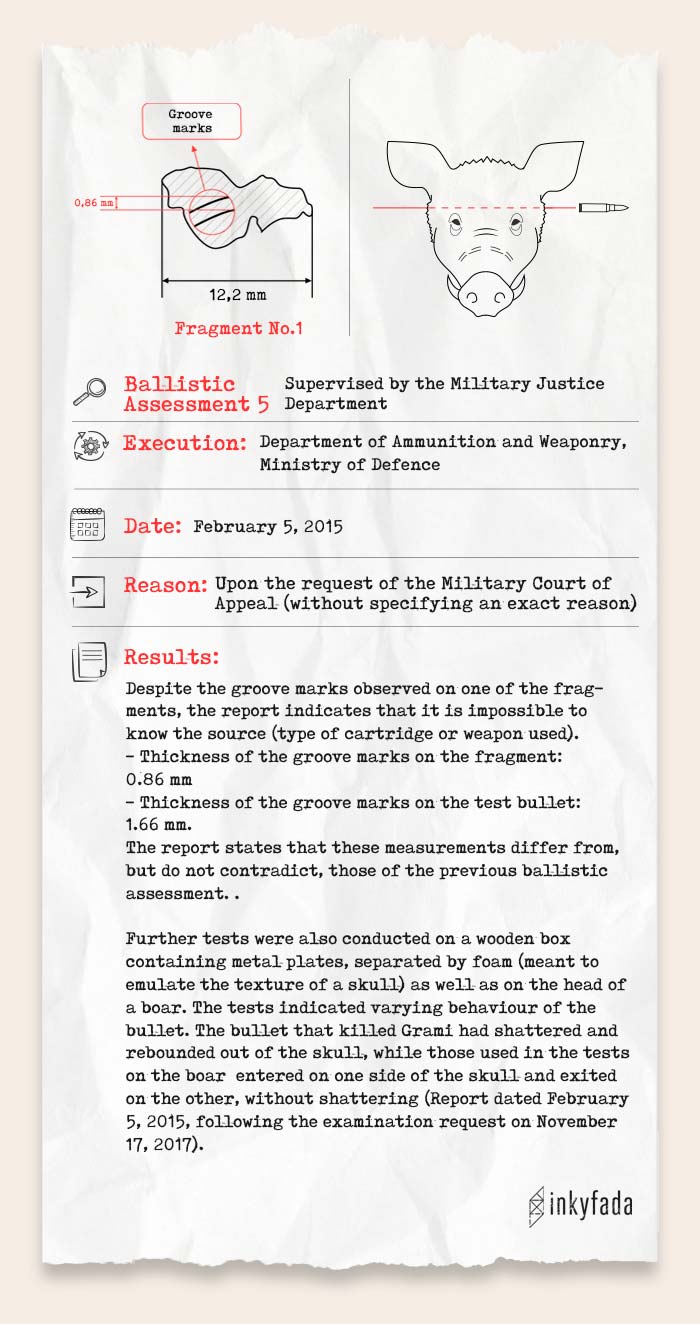

Upon the return of the case to an appeal phase, the court once more decided of its own volition, and without consulting any of the parties involved (lawyers of the accused, civil and military prosecutors, and those in charge of state litigation), to test the fragments for another, fifth time.

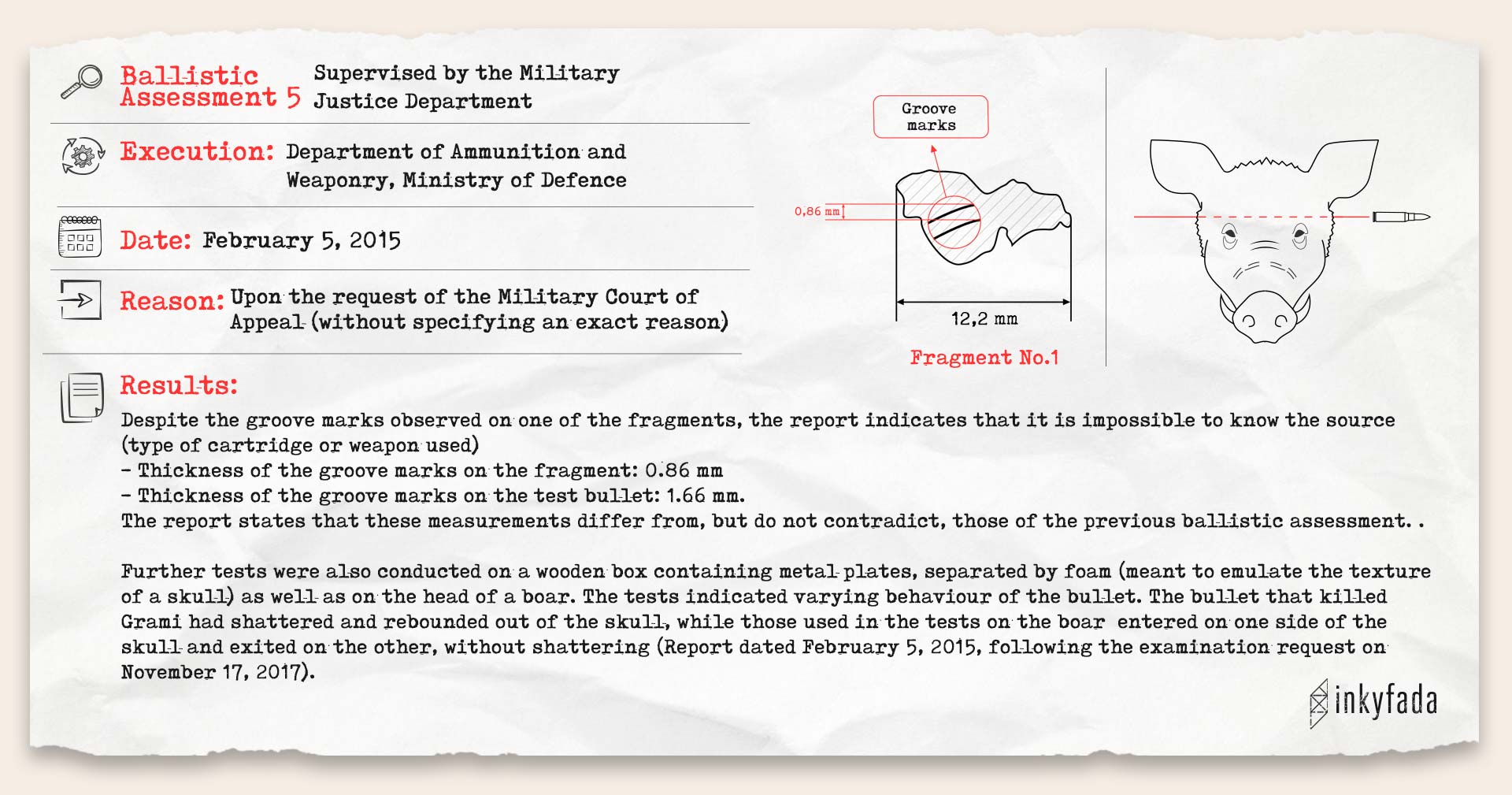

This fifth report, submitted by the Ministry of Defense, stated that based on the general appearance of the two bullet fragments, it is impossible to ascertain the caliber of the bullet or the type of weapon used.

The same report went on to say that during the assessment test shots, using a 7.62 mm bullet fired at the head of a hog, they found that unlike the bullet that killed the deceased (which ricocheted and disintegrated with fragments remaining inside the skull), the test bullet completely penetrated the animal's skull; i.e. it created two opposing holes, without ricocheting or disintegrating. Hence, the report concluded that "the bullet that struck Amine Grami is incompatible with the weapon suspected in the case". Yet, it should be noted that the test report mentioned neither the distance, nor the angle used during the experiment.

The last report furthermore concluded that the shot was fired from an angle of approximately 0 to 15 degrees in relation to the deceased; a finding that is only partially consistent with the previous test, which had found the angle to be 15 degrees and excluded the possibility of a horizontal shot due to the location of the suspect.

Appearing in court to speak about the tests he conducted, the expert supervising the fifth assessment explained that a more accurate laser device was not used to determine the distance and angle of the shot trajectory during the test.

Inkyfada asked an international laboratory specialising in ballistic science and testing (which asked to remain anonymous) to review the test reports carried out in Tunisia. Upon their assessment, their laboratory indicated that certain important information was missing from the reports, and that some of it was at times strange and incomprehensible. For instance, they referred to the use of steel in order to understand the fracturing of the bullet (the behavior of the bullet after hitting targets). Because, according to the external lab’s view, steel does not respond to the bullet in the same way as the skull does.

Experts from the international laboratory were also surprised that the Tunisian ballistic assessment team used a small wooden box with pieces of foam, reinforced with metal sheets, as a target to represent a human skull, and shot at it from a distance of 100 meters (or even without mentioning the distance as in fifth test). The tests were also carried out without any corrective measures (for example, emptying parts of the contents of the cartridge depending on the coordinates of the target and the origin of the bullet), in order to ensure that the speed of the bullet during the experiment corresponded to the case being reproduced.

It is also worth reminding ourselves that the actual distance between the firing point of the bullet (the sniper's position) and the target (the head of the deceased) was set at 130 meters by the fourth ballistic assessment, not 100 meters as mentioned in the above report.

The ballistic expert that we solicited also expressed surprise at the fact that the weapon of the accused had not been seized; a procedure that is both given and crucial in such cases, since it is the weapon with which any further tests are meant to be carried out.

The expert explained that it is indeed possible for different laboratories to arrive at different results using the same sample; results depend on a range of criteria such as the type and duration of tests, the equipment used, and the competence and experience of the investigators, all of which may vary in accuracy and sophistication. However, the four initial tests in question were carried out by the same party, the Department of Ammunition and Weaponry, and produced inconsistent, even contradictory results. This raises questions about how the court handled the large amount of data, and how this may have influenced the verdict.

Increasing doubts from the defence

Charfeddine Kellil, a lawyer and member of the defence committee, told Inkyfada that " it makes no sense for the results to differ so much from one test to another, unless the fragments were replaced by others".

Kellil said he has repeatedly asked the court to send the bullet fragments to a foreign laboratory for impartial testing, through a process that would not be supervised by the military justice system. The court rejected his requests, simply asking the experts who examined the bullet fragments to explain how they had arrived at the results they presented.

These written justifications by the experts did not satisfy the defence committee's questions, as the former only notified the court of the way in which the tests were conducted and the methodology used.

Kellil added that he had previously asked the court to hand over the fragments to the Sub-Directorate of Scientific and Forensic Laboratories of the Technical and Forensic Police, in order to determine to which extent they corresponded to the description in Report N° 15 dated February 2, 2011 (the first forensic examination at the request of the court). His request was refused.

The Inkyfada team met with Mr. Jamel Ben Slama (Head of the Department of Analysis and Testing at the Ministry of the Interior), in order to clarify the discrepancies between the ballistics report carried out by his team, and those of the Ministry of Defence. However, he emphasised that the tests that were conducted under his supervision were confidential, thus leaving many questions unanswered.

A ONE YEAR SUSPENDED PRISON SENTENCE

On November 18, 2015, the Military Court of Appeals in Tunis sentenced Mohamed Sebti Mabrouk (sniper and National Army Chief Warrant Officer N° 655 at the Technical School of the Army), to a one-year suspended sentence for manslaughter.

This decision triggered a wave of protests due the various complications that plagued the case, as well as downgrading the charge from ‘ premeditated murder under duress’ to ‘ manslaughter’, resulting in a reduced prison sentence without any new or additional evidence pertaining to the innocence or guilt of the accused.

Dr. Borhène Azizi writes in the book for “ Provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code”:

" The authority of an expert opinion is limited whenever there is other corroborated, consistent and sound evidence that could lead to discounting the outcome reached by the delegated expert, and this is on the basis of the principle of equality between all evidence, without preference for one or the other." (Provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code, Tunisia 2013, p. 163)

Yet this case, with all its contradictions and discrepancies, has revealed two fundamental facts: first, that a sniper from the National Army killed at least one person during the period of chaos that followed Ben Ali’s departure; and second, that the military justice system trampled on a great deal of evidence, and followed a policy of filtering and selecting evidence in order to close the case with minimum prejudice to the defendant and member of the National Army, even if this was done at the expense of the truth.

In addition to the two previous points, there is a third (no less important) point found in the fourth ballistic assessment report issued by the Department of Ammunition and Weaponry. The report revealed, for the first time, that the bullets used by the accused on the day of the incident (caliber 7.62 mm) belonged to the same type of ammunition distributed across the different units of the National Army, and that quantities of this type of ammunition had also been supplied to the Department for the Security of the Head of State and Officials. The final delivery of this type of ammunition was made in 2001, which implies that the army was not the only actor to possess this particular caliber before and during the revolution.