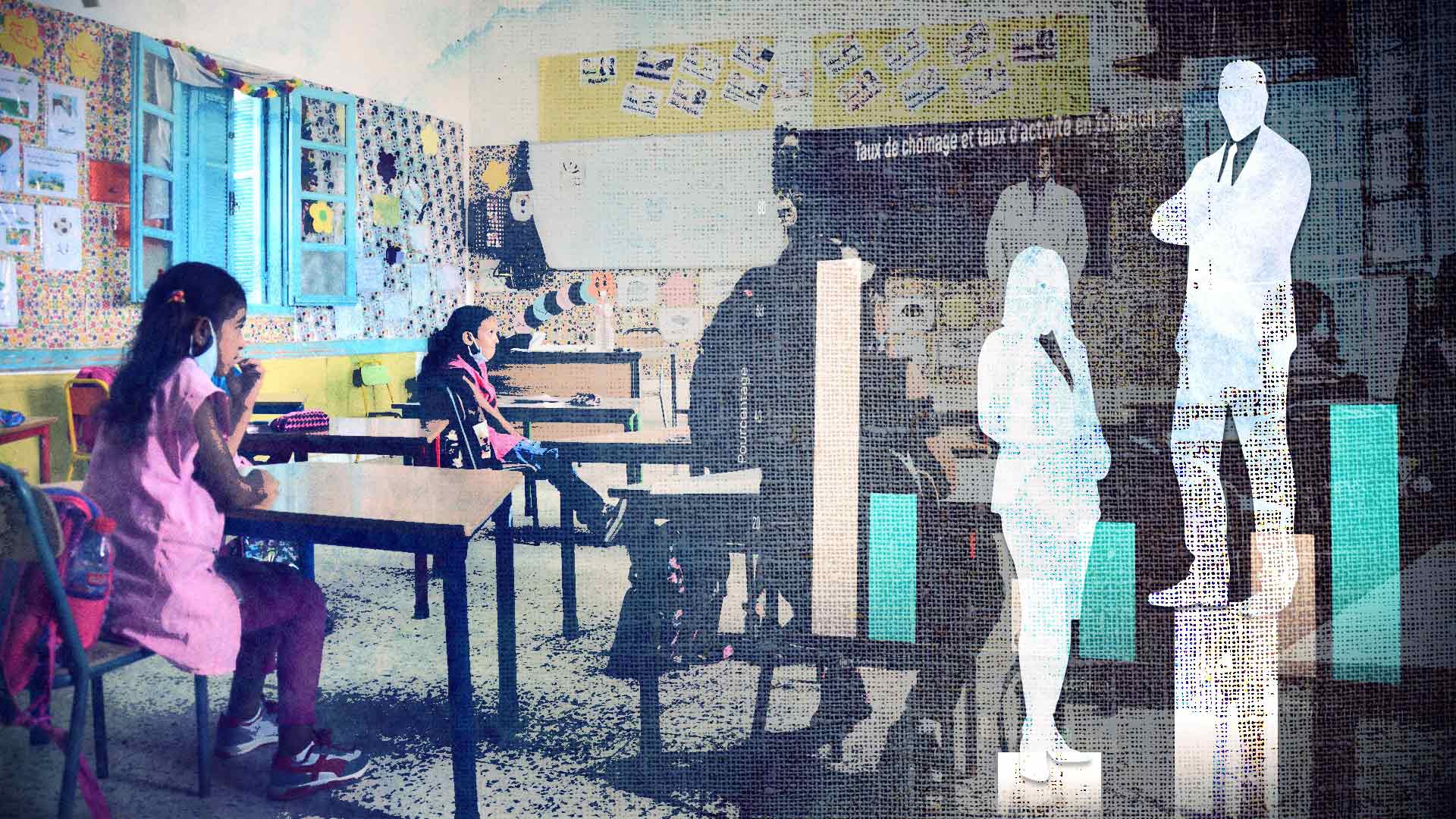

GIRLS, THE MODEL STUDENTS

The evidence is indisputable: girls do better at school than boys. The gaps are not only apparent at the time of the baccalaureate, but exist throughout the schooling process, from primary to secondary school: at each level of education, the drop-out and repetition rates for boys are higher and the progression rates lower, when compared to girls.

On the same subject

When combining data throughout the schooling process, the National Institute of Statistics arrives at the following conclusion for the year 2012-2013: the probability of a girl enrolled in the first year of primary school to complete secondary education is 42%, whilst for boys it is only 23%.

However, the higher achievement of girls does not apply to all subjects. The 2015 PISA survey, which compares the performance of 15-year-old students in various countries, shows that Tunisian girls are slightly more likely to have a lower performance rate in mathematics compared to Tunisian boys. However, the reverse holds true for reading literacy, where girls dominate.

Overall, despite these minor subject-specific variations in results, girls continue their studies for longer than boys, and this trend continues into higher education. According to data from the Ministry of Higher Education, in 2018-2019, 63% of students and 66% of graduates were women.

A PARADOXICAL OBSERVATION

These massive disparities in favour of girls can be put into perspective for certain categories of the population. Several studies have for example highlighted significant barriers to educational success for girls.

Girls who drop out of school generally do so for different reasons than boys, notes Dorra Mahfoudh: "Girls are more often objected to voluntary dropouts decided by their parents, whereas for boys, it is for pedagogical and academic reasons." The sociologist, who conducted a study in 2013 on women's access to public services in rural areas, observed that some parents who live far away from the schools, withdraw their daughters around the age of 10, if no one is available to accompany them, out of fear that they would be assaulted on the road. In other cases, girls are expected to help their parents.

In general, parents seem more willing to invest in their son's education than their daughter's, observes the researcher, who has witnessed the precariousness of many of her female students. For example, data from the Ministry of Higher Education concerning 2018-2019 indicates that men are overrepresented among private students. "When a boy doesn't succeed, people are more willing to pay for him to go to a private school than for a girl", Dorra Mahfoudh comments, based on her experience as a teacher.

Several sociological studies also point to the differential treatment of pupils by teachers according to their gender. In 2001, Nicole Mosconi, a French researcher in the field of education, recorded two primary school classes and measured the time spent with each student. The result of the experiment was that the teachers who were filmed devoted about 60% of their time to boys, compared to only 40% to girls.

They also interpreted their pupils' success differently depending on their gender, regarding it as the result of effort for girls versus intellectual ability for boys. If a boy does not succeed, teachers are therefore inclined to think that it is an accident or lack of effort, whereas if a girl faces the same difficulties, it is connected to her intelligence.

These different patterns of teacher behaviour, which are particularly noticeable in mathematics, are likely to play a role in the success of pupils, Dorra Mahfoudh points out: "The expectations placed on boys and girls can cause a Pygmalion effect". Behind this term lies a well-known sociological finding: when different expectations of success are projected onto pupils, they may end up being met accordingly, even though the pupils had the same level to begin with. In other words, if teachers believe that girls are generally less 'mathematically minded' than boys, it is likely that girls will end up actually lagging behind boys in the subject.

Beyond interactions with teachers, several recent studies point to a hostile climate for girls in the classroom or in the playground, adds Marie Duru-Bellat, a French sociologist specialising in educational policies and inequalities in schools. "At secondary school level, boys try to impose their law on girls. There is a lot of harassment and bullying, which may be minimal but is constant, it accumulates. I think it's very harmful for girls, they learn that boys are the ones who make the rules, that they must not take up space, and that they must stay in their place. Teachers and educational advisors consider this to be normal at that age and do not intervene much."

So why, despite all of these obstacles, do girls tend to stay in school for longer than boys?

A recurring argument is that boys are distracted by girls, which would explain why they do less well. This is a fallacy, according to Dorra Mahfoudh: "When we compared mixed and single-sex classes, we found no differences, except that the boys performed slightly better in mixed classes because it stimulated competition."

Some people suggest that the higher success rate of girls is due to preferential treatment by teachers. Two French sociologists devised a way to test this hypothesis in 2009. They asked 48 mathematics teachers to mark high school final papers, telling half of the teachers that they had been written by girls, and the other half that they had been written by boys.

There was no significant difference in the marking of papers attributed to girls versus boys. On the other hand, "teachers tend to mark weak and strong students differently depending on whether they are girls or boys", the researchers found. If a very good paper is written by a girl, it will be marked less well. On the other hand, the marker tends to be more lenient with a girl presenting a weak paper. The marking thus seems to reflect the prejudices of teachers, who unconsciously expect a girl to be less good in mathematics than a boy.

With regards to achievement gaps in specific subjects, no study attests to biological differences being present from birth that would predestine girls to be good at reading whilst boys are better at mathematics. On the contrary, several sociological results invalidate this hypothesis, according to Marie Duru-Bellat: "We observe, for example, that the mere fact of changing the way an exercise is presented considerably changes the success rate of boys and girls. If there was a biological barrier, this would not work. Also, in the PISA survey we always have countries in which girls do better in mathematics [for example in 2015: Finland, Albania, Indonesia, Trinidad and Tobago], which clearly demonstrates that if we had a biological explanation in mind, it doesn't hold up."

BETWEEN EDUCATION AND EMANCIPATION STRATEGY

Ultimately, sociology offers two main explanations for the greater success of girls at school.

"Girls do better because they arrive at primary school already psychologically prepared by their family upbringing to assimilate school norms. School norms require discipline, obedience, timetabling, care, and family norms teach girls exactly the same thing" , Dorra Mahfoudh analyses.

Conversely, the way boys are brought up is more at odds with the behaviour expected at school: "In order to learn, you have to be calm, stay in your chair, not talk to your friends, and obey a woman, especially at secondary school where many teachers are women. For a boy, especially in certain social circles, a man does not give in to a woman's orders or advice, but rather tries to oppose them", adds Marie Duru-Bellat.

The desire of girls to study also responds to a social norm: that of the active and educated woman, in a society where being a housewife is no longer valued, reminds Dorra Mahfoudh.

Marie Duru-Bellat insists, however, that young girls are not only passive in the face of social norms, but also actors in their own future: "It seems as if girls are submissive and conformist. On the contrary, they are reasonable, they have seen that more and more will be asked of them, so if they want to get something, they have to work at it, and they do. It's a strategy of adaptation to what awaits them."

Thus, investing in school is a strategy for women to offset the difficulties they will encounter on the labour market, but also to escape family control, according to Dorra Mahfoudh: "At university, they are far from the family, it is an opportunity to discover the world and to emancipate themselves. They try to succeed in order to assert themselves, to be recognised, to have an identity."

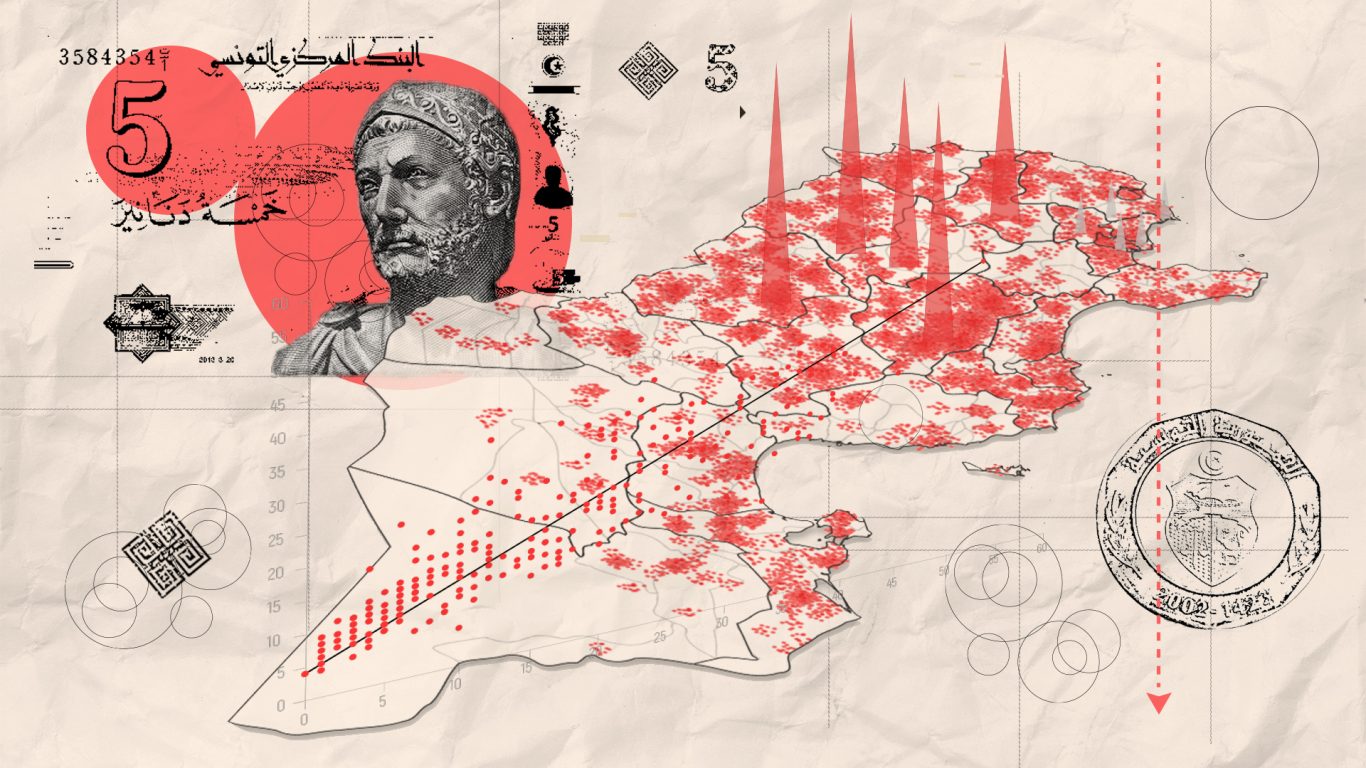

WOMEN ARE MORE AFFECTED BY PRECARITY

Despite their exemplarity at school, women suffer massive inequalities in the labour market. They are less active, earn lower wages, and are more unemployed than men. The gaps are particularly large among graduates, with a 20-point difference between the unemployment rate for women and men.

For Dorra Mahfoudh, it is the mismatch between the job offer and women's qualifications that explains their high unemployment rate: "The Tunisian job market offers low-level jobs. Women are generally found most often in textiles and domestic services: these are sectors where women with diplomas are not going to go!"

However, women are more willing to work below their qualifications than men, the sociologist adds: "That's why we often hear that women are responsible for unemployment, because they accept low wages, more difficult working conditions, and are less demanding. It's the same discourse as for immigrants who would steal the work of Westerners, while they are actually taking the jobs they don't want."

To explain the gender pay gap, we must also take into account the sectors that women themselves choose to go into, starting in secondary school. While they are in the majority in literature and experimental sciences, for example, they are in the minority in technical or computer sciences.

This continues in higher education, where one in four students are studying engineering, whereas only one in ten female students opt for this field.

Yet the sectors to which women turn are (more often than not) both the least socially valued and the least paid. How can this correlation between female presence and devaluation be explained? "There are entire sectors to which men no longer turn, such as teaching, because the salaries no longer attract them. It is becoming devalued, and therefore feminised. But at the same time, when it becomes feminised, it also becomes devalued. This can be explained by the fact that women are less unionised and strike less."

"WOMEN ARE STILL PERCEIVED AS MOTHERS"

The family lies at the heart of the problem of inequality in the labour market, according to Marie Duru-Bellat. "Women are still perceived as mothers. We always have the question in mind: what will happen when she has children?" she explains.

"The combination of the two careers: family and professional, means that women take maternity leave and fall behind. When two young people with the same diploma enter an administration on the same date, ten years later, we will find that the man has reached a better level than the woman. This is because the whole family burden was holding back the career", explains Dorra Mahfoudh.

The 2005-2006 time-budget surveys, in which the Tunisian sociologist participated, made it possible to quantify this phenomenon: on average, women spend eight times more time on domestic tasks than men. They spend 5 hours and 15 minutes a day on them, compared to just over 30 minutes for men. This division of labour necessarily impacts women's careers.