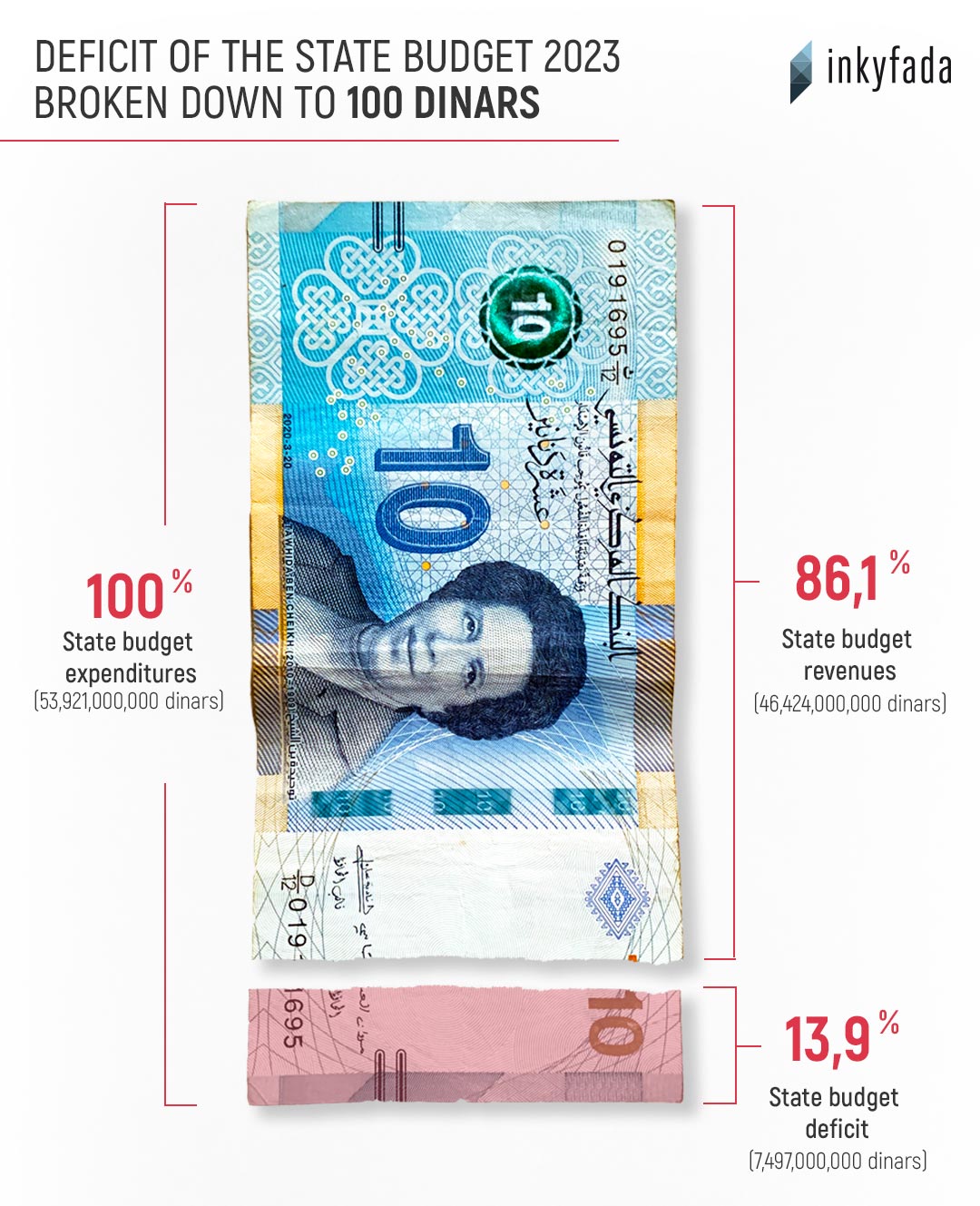

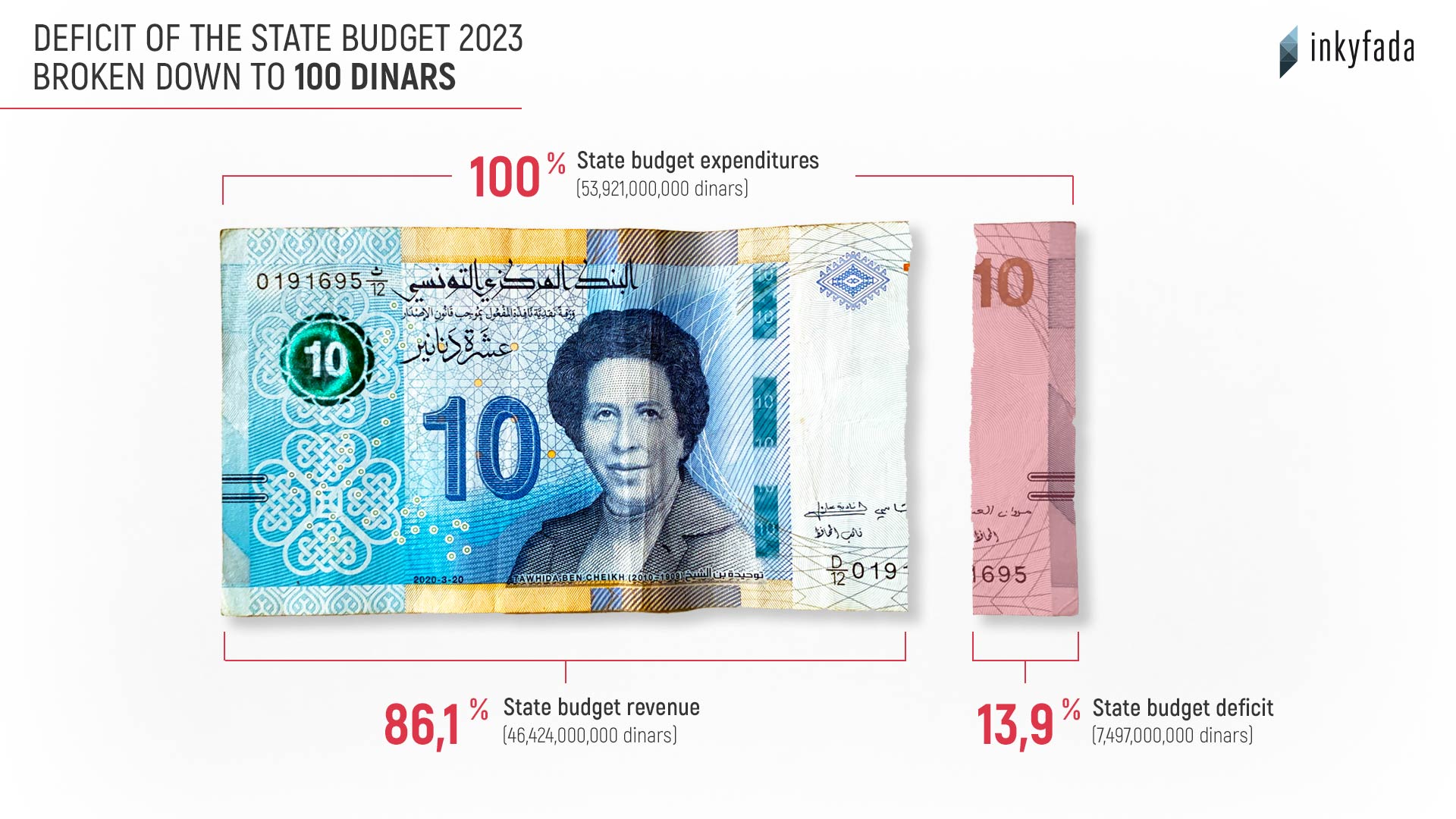

The government hopes to cover the vast majority of its budget deficit with a 1,9 billion Dollar loan from the IMF, which is currently being negotiated.

Tunisia has been struggling to finance its state budget for several years. While exogenous shocks such as the pandemic and the war in Ukraine are heavily impacting the country, especially because rising international prices are driving up subsidies expenses which are financed by public funds, there are also other, structural reasons responsible for these economic difficulties.

One of them is the country's economic development model, in particular its fiscal and budgetary policies, says Amine Bouzaïene, a researcher in social and fiscal equity. These fiscal and budgetary policies were recommended to Tunisia by international financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank starting from the late 1980s as part of the structural adjustment plans, which in turn lead to neoliberal reforms. “The overall development model is failing. It’s not producing growth and not distributing it fairly”, says Amine Bouzaïene. “The country is not relying enough on its own capabilities and therefore there is a need to borrow money in this vicious circle of debt and austerity”.

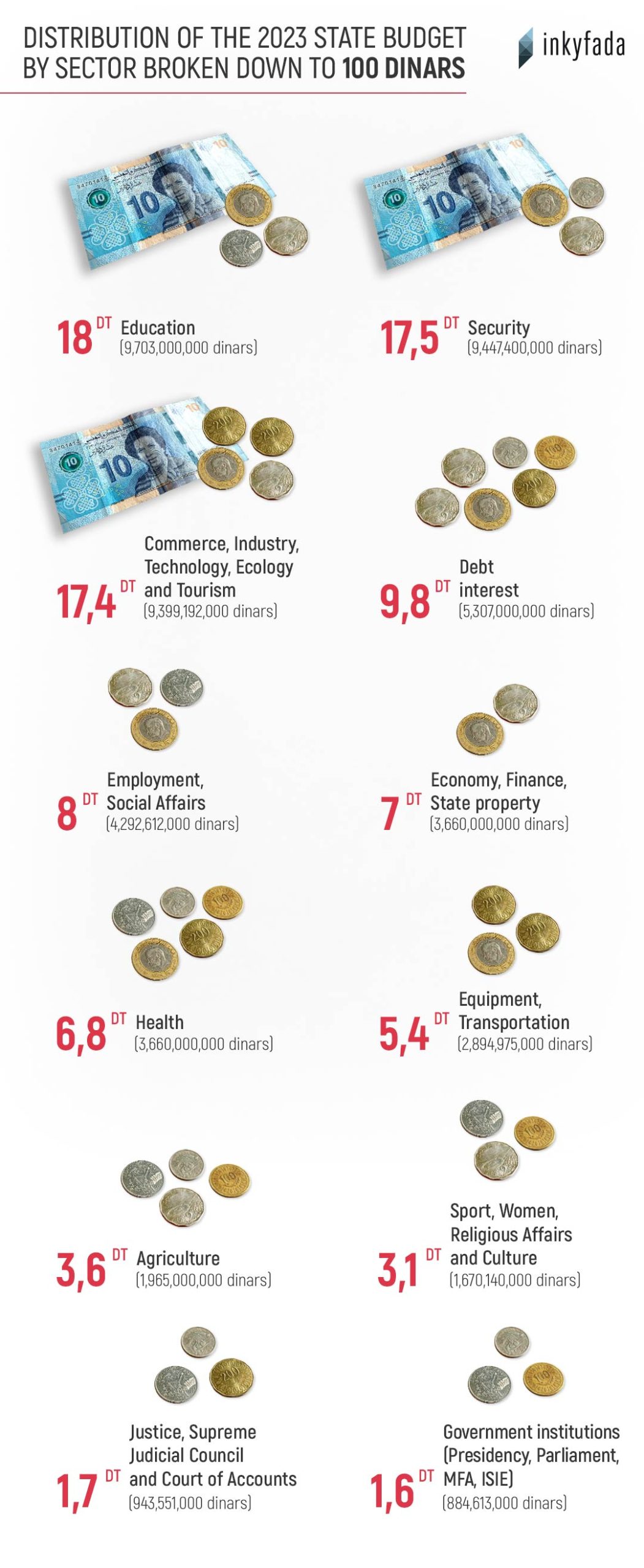

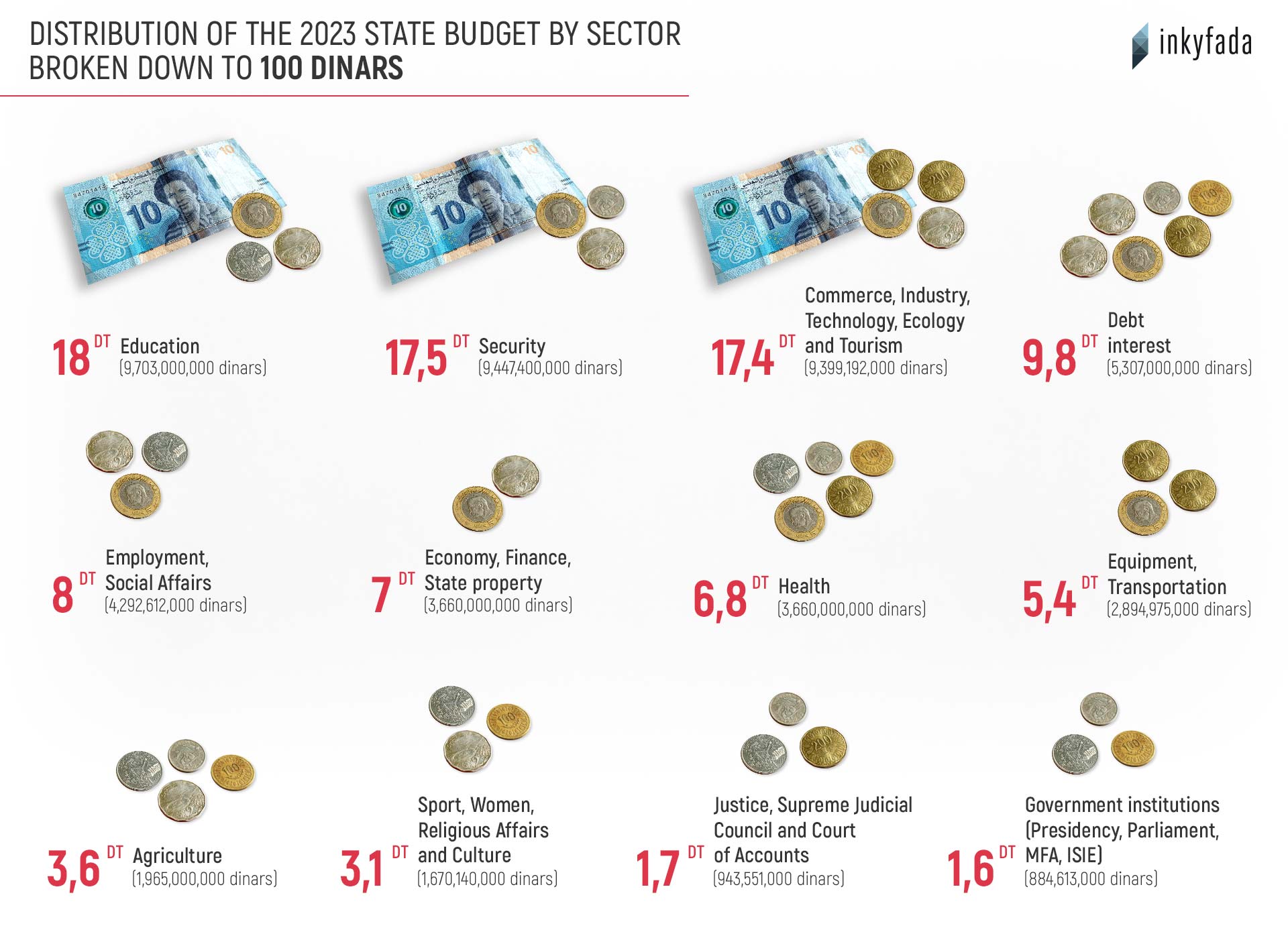

Which sectors will get how much money?

18 out of the 100 dinars state budget will be given to the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research. This is not surprising, given that education has traditionally been the highest priority in the Tunisian state budget.

The budget for the security sector continues to grow compared to previous years and will amount to 17,5 dinars out of the 100 dinars state budget for 2023. Another 17,4 dinars will go towards commerce, industry, technology, ecology and tourism.

Public health spendings will only make up 6,8 dinars out of the 100 dinars state budget for 2023, despite Tunisia having pledged to allocate 15% of its overall budget to healthcare spendings by signing the Abuja Agreement in 2001. With the public health system suffering greatly from regional disparities as well as lack of investments, material resources and medical personnel, it is vital that the Tunisian government keeps this pledge.

According to Amine Bouzaïene, this issue doesn’t only apply to the public health sector: “It's a budget that is very low for all ministries given our needs in all these public services. The challenge is how to increase it for all ministries”.

The budget allocated to the judiciary in general including the budget for the ministry of Justice as well as the Supreme Judicial Council is at the bottom of the list with only 1,7 dinars out of the 100 dinars which make it nearly impossible to think about any serious and concrete reforms to improve the functioning of its bodies and the efficiency of justice.

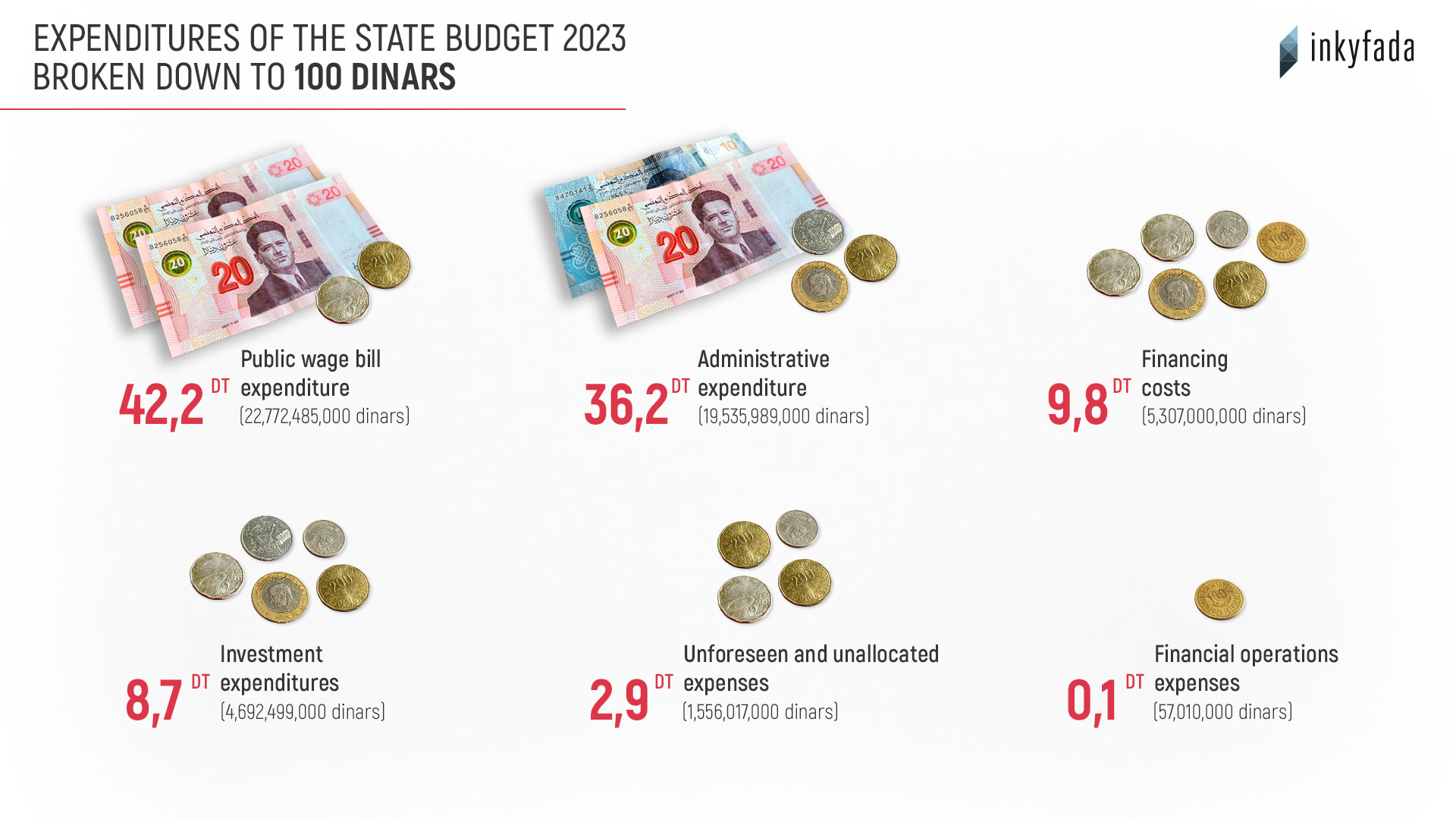

What will the money be spent on?

Looking at the type of expenditure that the state budget for 2023 will be spent on, one can see that the largest cost factor is the public wage bill, which takes up 42,2 dinars of the 100 dinars state budget. Tunisia's public wage bill is one of the highest in the world, accounting for 14,2% of the country's GDP.

Under pressure from the IMF, the Tunisian government is trying to reduce the public wage bill through different measures like for example the limitation of recruitment in priority sectors and the reduction of the number of graduates from vocational schools. Despite these measures, the public wage bill will actually further increase by 4,3% in 2023 compared to the previous year and is thus largely responsible for the increase of the state budget.

For Amine Bouzaïene, however, the problem is not about the wage bill of Tunisia being too high, but rather the overall budget being low. “The whole problem lies in the fact that Tunisia does not produce sufficient growth, that it has a low GDP and a low budget”, he says. This can be seen in the understaffing of many sectors such as health, education and the judiciary. And even the people who are employed in these sectors often find themselves in precarious situations, where they are being paid very little and very late.

The second largest expenditures after the public wage bill is administrative expenditure which accounts for 36,2 dinars out of the 100 dinars state budget. These costs are mainly made up of intervention expenses which consist of transfers that go towards households, businesses and other public bodies.

16,4 dinars out of these 36,2 dinars will be spent on subsidies. Compared to the previous year, subsidies are thus expected to fall by around one fourth, as a result of the government’s overhaul of the subsidy system. This is a very radical cut to a system that many Tunisians rely on in order to meet their daily needs, especially considering that between the years 2010 and 2020 spendings on subsidies increased by an average of 15% per year and that with global inflation, international prices will likely keep rising.

What stands out when looking at the types of expenditures of the state budget is the high amount of money going towards debt service costs, which include all costs that arise in connection with taking out and repaying of loans. 9,8 dinars out of the 100 dinars state budget will be spent on repayments, while only 8,7 dinars will be going towards new investments.

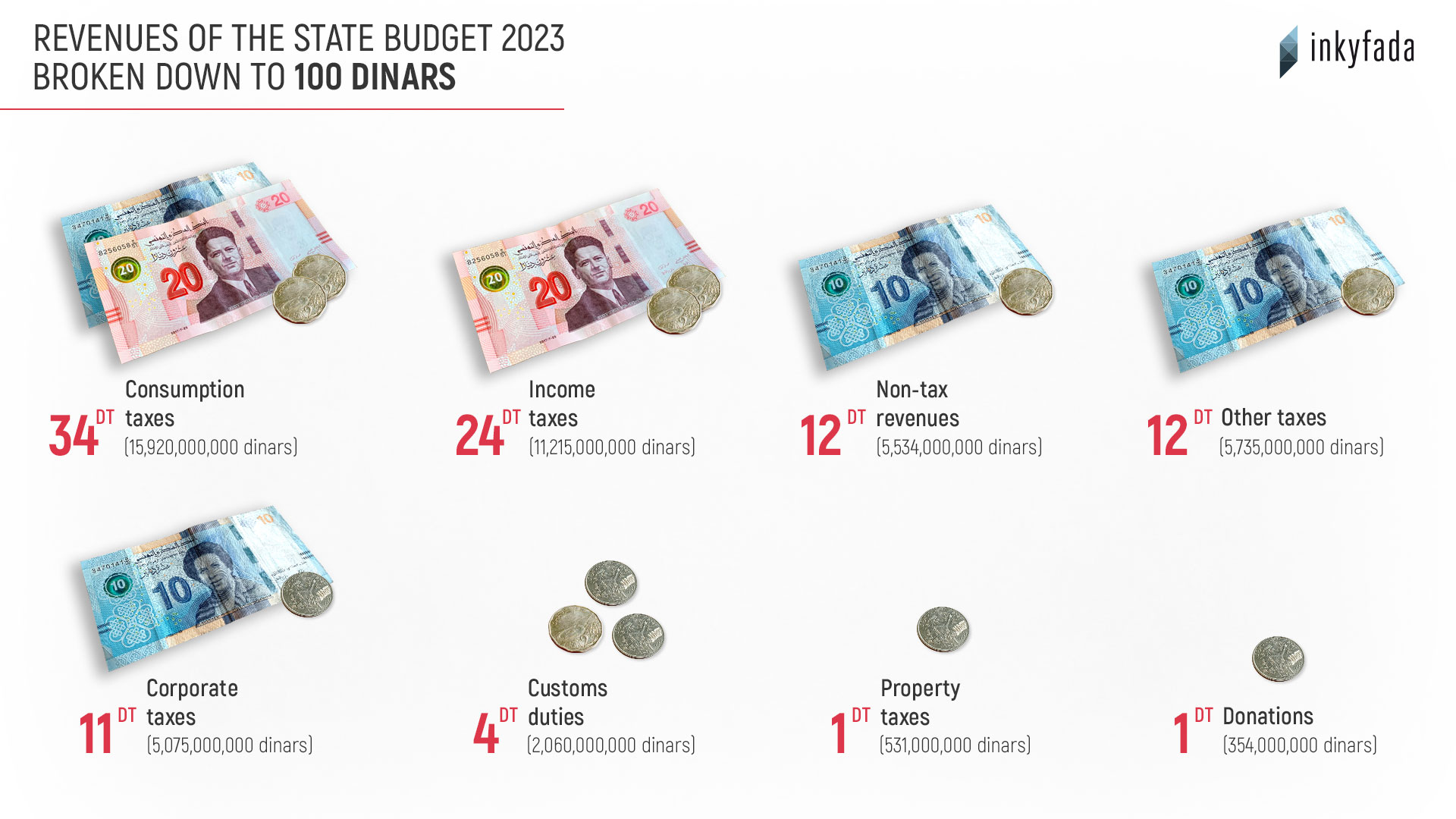

Where does the money come from?

The state budget of Tunisia is almost entirely financed by taxes. Broken down to 100 dinars, around 34 dinars of the money will be collected through consumption taxes which are levied on the consumption of goods and services in Tunisia. Revenues from income taxes only make up around 24 dinars and revenues from corporate taxes around 11 dinars.

From a “tax-fairness perspective” the state budget thus “relies on the most unfair taxes, especially consumption taxes”, says Amine Bouzaïene. Up until 2014, income tax and corporate tax had a roughly equivalent yield. But as a result of tax cuts, tax benefits, and massive tax evasion, corporate tax revenues have drastically declined. “This demonstrates that Tunisia has a financial lever, but the distribution is completely inequitable, especially between household taxation and business taxation”, says Amine Bouzaïene. “Tunisia is not exploiting its fiscal potential, its own resources, its own revenues”.

In contrast, 13 dinars out of the 100 dinars state budget for 2023 will come from non-tax revenues. This includes for example profits and income from public companies and property, administrative fees and revenues from fines and penalties. It also includes donations from foreign states or state unions.

If Tunisia’s tax system were more efficient and fairer than it is now, the available resources could be increased. It is estimated that the Tunisian state loses 25 billion dinars each year due to tax fraud and tax evasion, which is equivalent to nearly half of the state budget for the year 2023 and around one fourth of the country's GDP.

This loss of tax revenue could be reduced by implementing a fairer tax system, which is a “prerequisite for taxpayers' voluntary compliance with taxes”, according to a report on fiscal justice which was published by Al Bawsala in June 2022.

The report suggests that a fairer tax system could be achieved, for example, by reducing tax exemptions that benefit the wealthy and by reintroducing progressive taxation, which would result in high-income earners paying a higher proportion of their income in taxes than low-income earners.