"There will be food in 30 minutes and the doctor is coming as well," announced Amira. She later returned in a car loaded to the brim with boxes full of donations, mainly clothes, and medicine, accompanied by a volunteer and the doctor. The latter immediately started treating patients from the front seat of the car. The first one was a young man with a wobbly face, wrapped in a wool blanket, suffering from kidney stones. The next one had a foot injury after having jumped from his balcony to escape from the police.

Since February 21, over a hundred people have set up camp in front of the offices of the UN migration agency, in the hope of being repatriated to their country of origin in sub-Saharan Africa and fleeing the racist and xenophobic violence that has spread across the country. Faced with this crisis, the deafening silence of international organizations such as the IOM and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) is shocking, while a number of local solidarity movements have been mobilizing in all discretion.

On the same subject

A humanitarian crisis

Aboubacar and his two brothers, all from Guinea, have been sleeping outside the IOM for several weeks, hoping to be repatriated: "We don't have a choice," murmured Aboubacar, "we have nowhere to go." February nights are chilly, and they've been struggling to sleep under the black plastic tarps they've been using for shelter: "Sometimes we stay up all night by the fire without sleeping." They are still unsure whether to stay on the street, while waiting for their appointment set for August 18, or to attempt the dangerous sea crossing to Europe.

On the same subject

Inkyfada met them a couple hundred meters from the building, for a discreet interview: a few hours earlier, the police, who were called by IOM security personnel, had checked a volunteer on the spot. One of the brothers was scanning the streets during the entire discussion, and the arrival of the IOM head of security brought the conversation to an end.

Aboubacar, his brothers and their friend lived quietly in their small apartment in Tunis. As the group was about to have dinner one night, they heard a loud noise, "at exactly eight o'clock," Aboubacar recalled. The noise came from the floor below, as the police forcibly removed their neighbors: "they kicked the door open like this," said Aboubacar, mimicking a violent kick, as if they were breaking the door down.

Aboubacar and his brothers were able to flee, but the police caught their roommate, and they haven't heard from him since.

Shaken by what had happened, they spent the night at a friend's house and went back to their apartment the next day, but to their surprise, they noticed that most of their belongings were gone. "They took our phones, our passports... they ripped everything to pieces," recounted Aboubacar. All they had left were the clothes they were wearing and some plastic flip-flops that have seen better days. Their landlord kicked them out for good and threatened to call the police. Their host from the night before was also evicted from his apartment. Aboubacar and his brothers had to spend two nights outside, and then, "after the third day, we came here [to the IOM]."

An improvised 'camp'

Aboubacar and his brothers were gathered with more than a hundred other people in front of the IOM offices: the building overlooked an open courtyard, where the younger ones played with an old yellow ball. Aside from the phones, often with dead batteries and no internet connection, it's one of the few distractions that keep them busy all day.

The UN building extends to an adjacent alleyway, now packed with plastic tarps and tents, in which women and children - who are gradually being moved to hotel rooms - are settled first. Clothes are hanging on clotheslines attached to trees. A little further on, a mountain of stinky garbage keeps on growing by the day.

Sub-Saharan migrants in front of the IOM sleeping next to a pile of garbage. Credit: Julia Terradot.

A series of arrests, assaults and deportations

Since February 7, 2023, at least 800 people have been arrested as part of a campaign targeting undocumented migrants in Tunisia. Lawyers Without Borders (ASF) has followed up with the lawyers and courts available to them, and found that many arrests haven't been recorded and that the number could be as high as 2000.

The police are checking people they "presume to be migrants based mainly on the color of their skin," explains ASF's Marwa, "and that's why some Tunisians are also being arrested," along with refugees.

The number of arrests, the detention conditions - "zero respect for their rights," resented Marwa - and the harsher sentences have shaken the civil society. Sentences for illegal residence or border crossing range from one to six months in prison, depending on the court and the region. "It used to be a two-month suspended sentence or a fine," clarified Marwa.

For the record, Kaïs Saied's statements on February 21 echoed a racist and conspiratorial narrative against Sub-Saharan Africans in Tunisia, which had been mainly limited to social networks.

Unspeakable violence then erupted in the country. "Racism has just been 'institutionalized' and it's like a free pass to do anything. It's a lawless situation," sighed Marwa. For the past month or so, Moncef, Marwa's colleague at ASF, has been receiving repeated calls from beneficiaries who have been "beaten, humiliated by [Tunisian] citizens," or even raped.

"The donors are also afraid of being arrested," continued Moncef, and hundreds of people have found themselves homeless, after being evicted by their landlords.

A spontaneous humanitarian aid

Amira began to help when she came across the situation in front of the IOM as she was walking past the building with a friend. "I was talking to people and crying at the same time. We felt ashamed," she recalled.

Since she works in the same neighborhood, she immediately started charging phones in her office. For food needs, "we just brought anything, we didn't really know what to do," admitted Amira. The menu for the first few days was: "eggs. We would boil them and bring back hot eggs, and milk for the kids as well."

As the days went by, the needs became clearer: "we started to have more visibility," rejoiced Amira. Food, water, clothes and medicine donations mainly came from her colleagues, employees of the hospital where her mother works, and solidarity associations.

Amira has made a habit of sending any immediate needs to a welfare group on the encrypted messaging app Signal: "I'm often in a rush, so I sometimes have to run to send voice notes and it's not easy," she laughed. Information is gathered and relayed until the needed donations reach their destination.

Sub-Saharan migrants resting and playing ball in front of IOM. Credit: Julia Terradot.

IOM's Silent Stance

Most of the people in front of the IOM have nowhere else to go. They left in a hurry, having been kicked out of their homes and robbed of their belongings. Without papers, money, or even clothes, the victims are almost entirely dependent on local solidarity movements that have been formed over the weeks.

The IOM is not part of this effort, even though it promotes the rights of migrants and claims to be responsible for providing them with humanitarian assistance, regardless of their status. If outside help like Amira's stops, "we would all die here," said Aboubacar, who was denied water by the international organization's security staff the day before.

Amira also deplored the IOM's lack of action, even though the situation was directly unfolding right outside its offices:

"Right now, it's an emergency. We're no longer talking about asking for an agreement to get funds out. We're really in a state of war. And it's going to last."

February 21 marked the beginning of the crisis. However, it wasn't until March 8 that the IOM issued a first statement acknowledging the presence of "migrants" with "different needs" in front of their Tunis headquarters, but without announcing any particular measures.

When contacted by inkyfada, the IOM declined to answer our journalists' various questions. It then referred our team by e-mail to the central office, located in Cairo, which simply provided the link to the March 8 statement and indicated that the organization "is not offering any interviews or further comments at this stage ".

Depending on their country of origin, undocumented migrants are reliant on the IOM for repatriation, as embassies rarely allow nationals who have arrived illegally on Tunisian soil to be brought back.

For instance, "those who left [Côte d'Ivoire] without papers are not considered Ivorians," said Jean-Bedel Gnablé, President of ASSIVAT (Association of Active Ivorians in Tunisia). Consequently, these people are not eligible for repatriation flights organized by the Ivorian Embassy. Since the beginning of the crisis until March 14, the Ivorian government in Tunisia has allowed the return of 750 nationals.

Jean-Bedel also tried to contact the IOM through his association, but his call for support fell on deaf ears.

"I don't understand why those in charge of dealing with the migrants' situation can't provide assistance to people outside their offices," he lamented.

Theoretically, these people should be able to enroll in the IOM's Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) program, which according to their website allows for the "safe and dignified return and sustainable reintegration" in countries of origin. The exact number of possible voluntary returns isn't known. Most of the people sitting outside the agency will have to wait several months for an interview, and others don't even have an appointment yet.

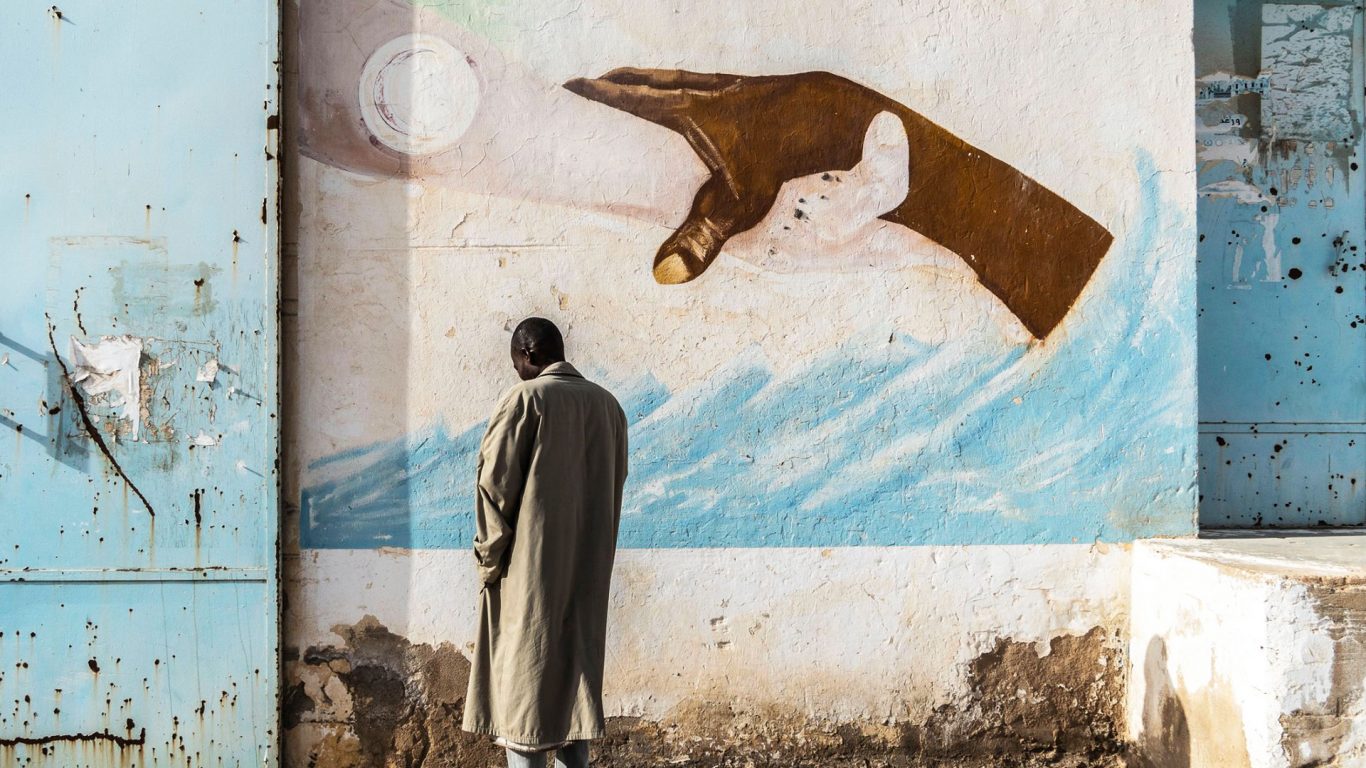

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Tunis. Credit: Julia Terradot.

Fear and confusion among the victims

Ekon came to Tunisia last year from Nigeria to work and send money to his family. Kicked out of his apartment, he has been sleeping outside the IOM and reluctantly signed up for the voluntary return program. He and his friend Obi, also Nigerian, are dreading their return to a violent daily life.

"We don't want to go back [to Nigeria], but we're out of options. There are too many problems and murders. People are dying every day. The only way to defeat them is to join them and I can't shed blood," Ekon admits.

The conditions in Tunisia aren't any better. A few days earlier, three Tunisian youngsters chased Obi down a street in Tunis in broad daylight and started throwing stones at him in front of passers-by. He managed to escape, but the brutality of the attack still haunts him.

Today, the makeshift camp outside the IOM is the only place in Tunis where Obi feels relatively safe. "Tunisia is an African country, yet they call us 'Africans' because we’re black," commented Obi.

"I don't want to rely on someone to pay for my rent and food. I want to work, I want things to settle down, and I want to move on. I want to be free," Ekon says.

Ekon was staring at the ground and shivering in his jacket that a volunteer gave him: "When I got here last year, it wasn't like this. The Tunisians were very nice. I'm very surprised," said Ekon. The group around him nodded in unison. "We're all surprised," confirmed one of them.

Protests in front of the UNHCR in Tunis

A few hundred meters from the IOM, Mohamed and a dozen other people were silently protesting the neglect of another UN agency, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The members of the sit-in, all of whom are refugees with the UNHCR, were demanding relocation to a country where they would be safe.

In Tunisia, UNHCR, in partnership with the Tunisian Red Crescent, is the only organization that can provide asylum-seeker status. Tunisia has no protective legislation or national body to review asylum applications.

Mohamed, a Sudanese refugee, has been in Tunisia for three years. Last April, he was already protesting at the Zarzis agency, then outside the headquarters in Tunis against his expulsion from the UNHCR shelter in Medenine.

On the same subject

After six months of struggle, the organization promised Mohamed a housing solution that never materialized, and he had to accept the UNHCR's inaction.

Then came the February 21 speech, and Mohamed's life took a turn for the worse: "I lost my job, I lost my house," he said indignantly.

"Right now, it's worse than Libya or Afghanistan. I have a refugee card. If I go anywhere to ask for work (...) This card is useless," Mohamed laments. "I'd go anywhere, as long as we are respected (...) we are not safe in this country because of racism."

Mohamed set up in front of the UNHCR in Tunis with a group of protesters, but the building's security called the police and he was kicked out once again. "They [UNHCR and its staff] won't help me. They won't give me anything."

He decided to sleep in front of the IOM and to go to the UNHCR every day, from around 7 a.m. until nightfall. He gradually gathered other protesters and together they demanded resettlement to a safe country.

The UNHCR offers resettlement, which is available only to refugees, but according to its website, "less than 1% of the world's refugee population" is considered for resettlement. When questioned by inkyfada, the UNHCR declined to answer questions.

Tents lined up in front of the IOM. Credit: Julia Terradot.

Discrete solidarity

Another presidential statement was issued on March 5, listing measures that would simplify procedures for foreigners residing in Tunisia, such as the issuance of residence permits.

"It's too little too late," complained Feriel, an activist with an independent collective, a solidarity group formed in opposition to the Tunisian State's racist campaign, "I don't even see how these measures they've decided to take can make up for the harm that's been done and reassure people and give them some hope. It's just utter disillusionment."

The collective brought together different members of the Tunisian civil society to decide on the next step to take: "It was a total mess, but we felt that we had to react," added Feriel.

They organized themselves to provide social and legal aid, among other things, in support of the victims: "Many people have shown solidarity. But we're still understaffed given what's going on, because the consequences are beyond measure," explained Feriel.

The group has been using the emergency mechanisms previously put in place by established NGOs, however, these processes are still inadequate given the extent of the crisis, which "is affecting all life aspects".

Solidarity is a risk that the collective has anticipated. Feriel mentioned the example of people who might have to violate article 25 of the 1968 law by transporting migrants to secure accommodations or hospitals.

However, this article also leaves "some room for interpretation" continued Feriel, "Because what does 'knowingly' mean? If I take a migrant to a hospital today and they check their papers and find out that they are in an irregular situation, I can say that I had no idea. It's my word against the police's," she explained.

The group has also been working discreetly to protect its members from online harassment. On Facebook, accounts have threatened association members in Tunisia to deter them from pursuing their solidarity action: "We act in a secret and clandestine manner so that we don't have to put up with this kind of stuff." Everything is anonymous, no more Facebook posts, and exchanges are done via encrypted applications.

The group's protective mechanisms have restricted their ability to act despite the tremendous needs. The independent collective is working "by word of mouth", Feriel specified, and the mobilization messages are sent privately.

This approach "limits our ability to do so many things," says Feriel, "because we don't get enough donations and because people have a hard time trusting us. But it's really our only option."

Being quite outspoken on social networks, Jean-Bedel of ASSIVAT also denounced the lack of action by international organizations and the injustices against Sub-Saharan African nationals. And this stand wasn’t without its risks: "I have been receiving death threats (...) we have been following you, we know where you live, we know where you are," but these intimidation efforts haven't deterred Jean-Bedel from pursuing his solidarity action: "I'm not hurting anyone."