In Tunisia, as elsewhere in this world, marriage is considered a central pillar on the path to self-accomplishment. Moreover, in order to celebrate this union, no effort is spared to make the wedding a success. Everything can be compromised in order for this mortal moment to be, at the level of the hoped-for result of what will come after, and in order to immortalize it forever.

Moreover, to make such weddings indelible memories, it is customary for families to get a photographer. "It is an indispensable element in weddings, "says Amine Landoulsi, a photographic correspondent, also admitting that"the presence of the personal side of photography is really less, we are in a consumerist dynamic that is increasing and accelerating, so the wedding photographer has become more like the cook, the band or the rest of the interveners".

Amine sees this as one of the reasons why wedding photography suffers from a negative image. "There is a connotation in our photographic world, especially in Tunisia, that makes it as if the title of wedding photographer is an insult,” he says.

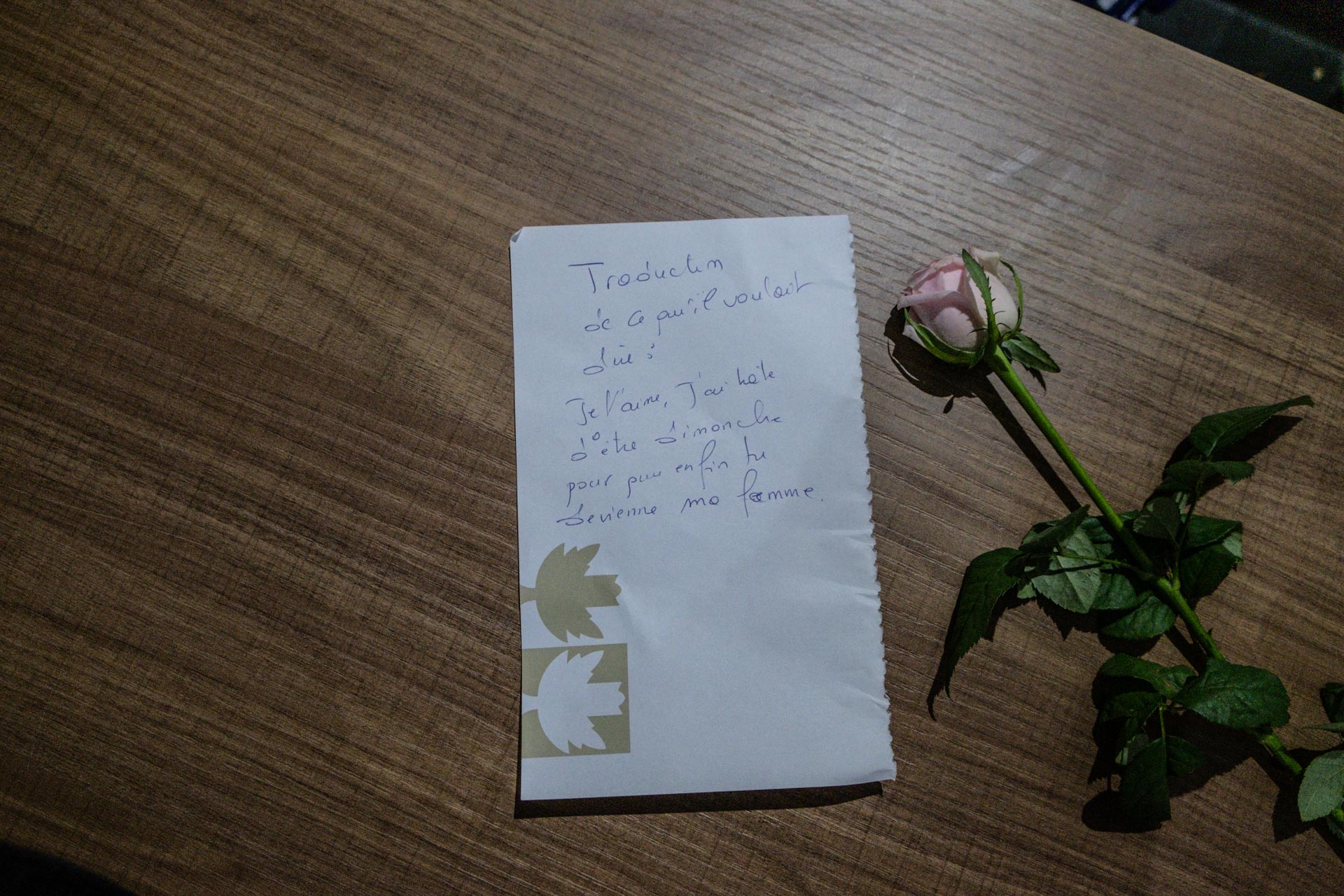

The photographer does not see such a cruel image justified, on the contrary, Amine Landoulsi appreciates this exercise, which he performed several times. "It's an honor to film The Wedding and the pairing of two people!". He also points out the great pressure that this task represents "we are obliged to paint this moment in pictures, whether the price is 100 dinars or 10.000 dinars. And the worst is when you fail at it, it's a disaster," says the reporter giggling.

Although this series is centered on marriage, and the photographer has been paid for his services at a number of weddings, he does not consider or describe himself as a wedding photographer, as Amine Landoulsi mainly practiced photojournalism. In January 2011, he worked on immortalizing the events of the Tunisian revolution.

Later, he collaborated with The Associated Press and then Anadolu Agency, he covered demonstrations, political events and Tunisian news in general, until one day he decided to abandon this profession after being fired from his job. "The correspondent conveys life as it is, but life has become difficult," he says, referring to the position he held.

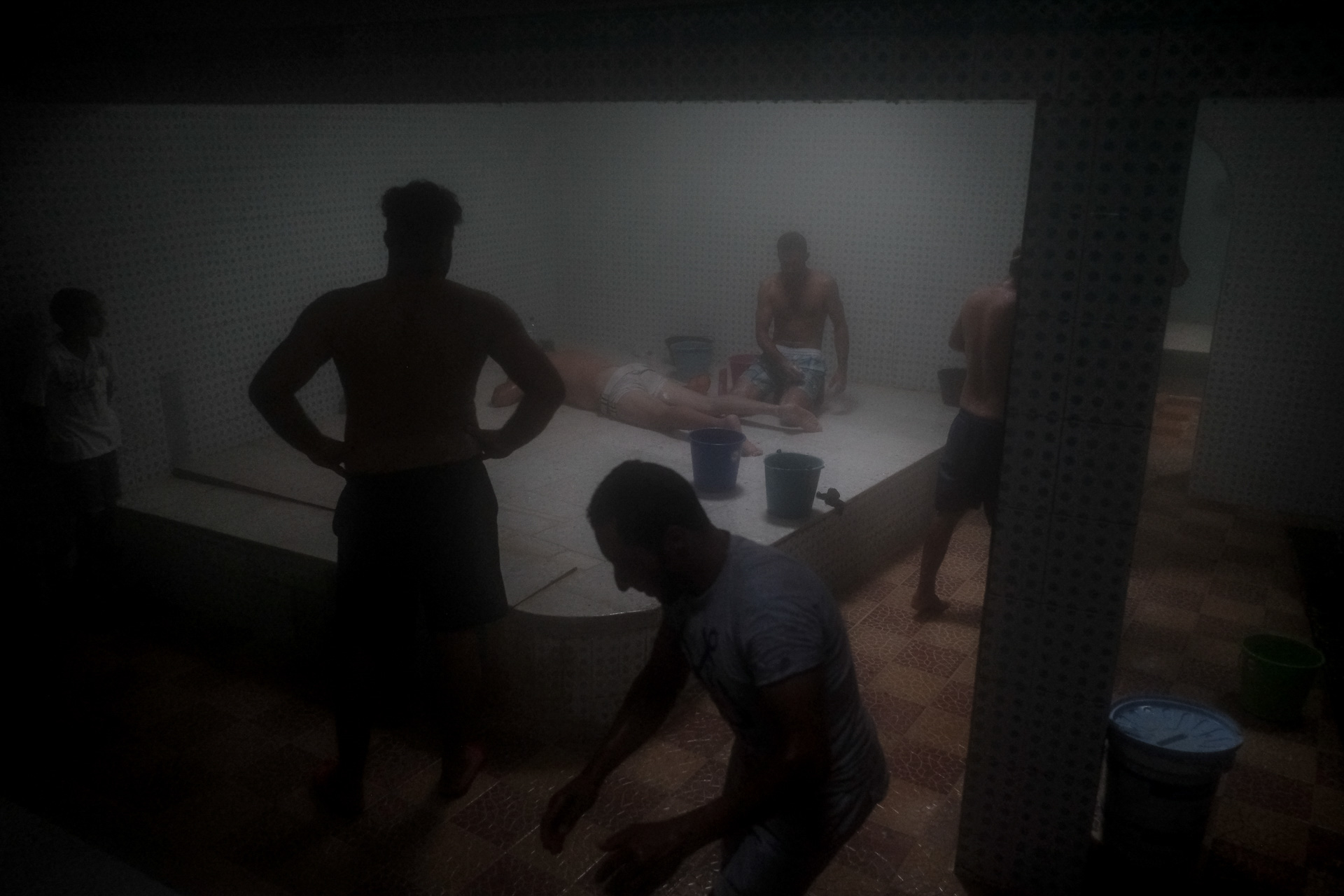

The festive atmosphere extends to the Hammam (a communal bathhouse), where the future groom, after a while getting very dirty, is blessed by the pampering and care of his friends. Al-Samaa, Nabeul, August 2017.

A cheerful and even somewhat childish atmosphere, according to Amine Landoulsi's description, is punctuated by throwing eggs,flour, Mlokhiya (Mallow) and others, to the tune of Zokra. Al-Samaa, Nabeul, August 2017.

The photographer recalls that at that time he was "looking for emotions". On the weekend following his dismissal from work, he went to the wedding of one of his relatives. "I spent three days with a young man about to get married," and from there, he turned his back on the dangerous events that he had been following in the past and focused on the positive aspects of life, including marriage. "I saw only surprises," says Amine filled with nostalgia.

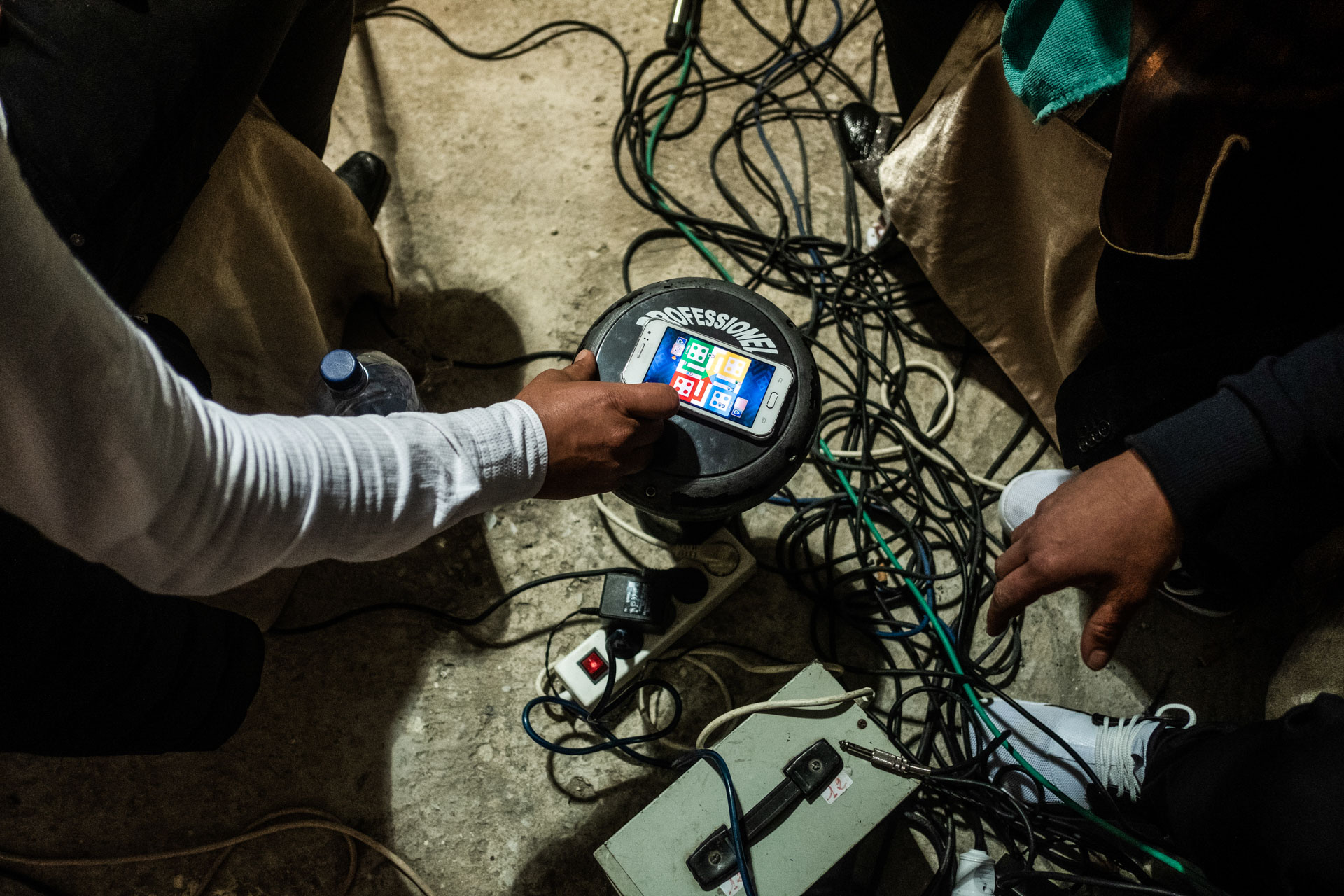

He then started a personal project in parallel with his immersion in photos he had taken at previous weddings, giving them a modified look, saturated with his previous experiences as a photojournalist, even talking about the "wedding report". The joys and everything that hovers around have become his new field, which he describes as not much different from the events he covered in the past. "I found all the ingredients: rioting, screaming, police raiding at one o'clock in the morning..."he says. The photographer has since done it many times again when he was invited to other weddings, on the basis of which he continued this series.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.