By 'artisans', Moez Cheikh refers to the owners and managers of popular grocery shops, as well as sweet makers, for whom the month of Ramadan is an important time to sell their products. Despite the crisis, there is an abundance of these products, which are fried in oil and mainly composed of flour and sugar.

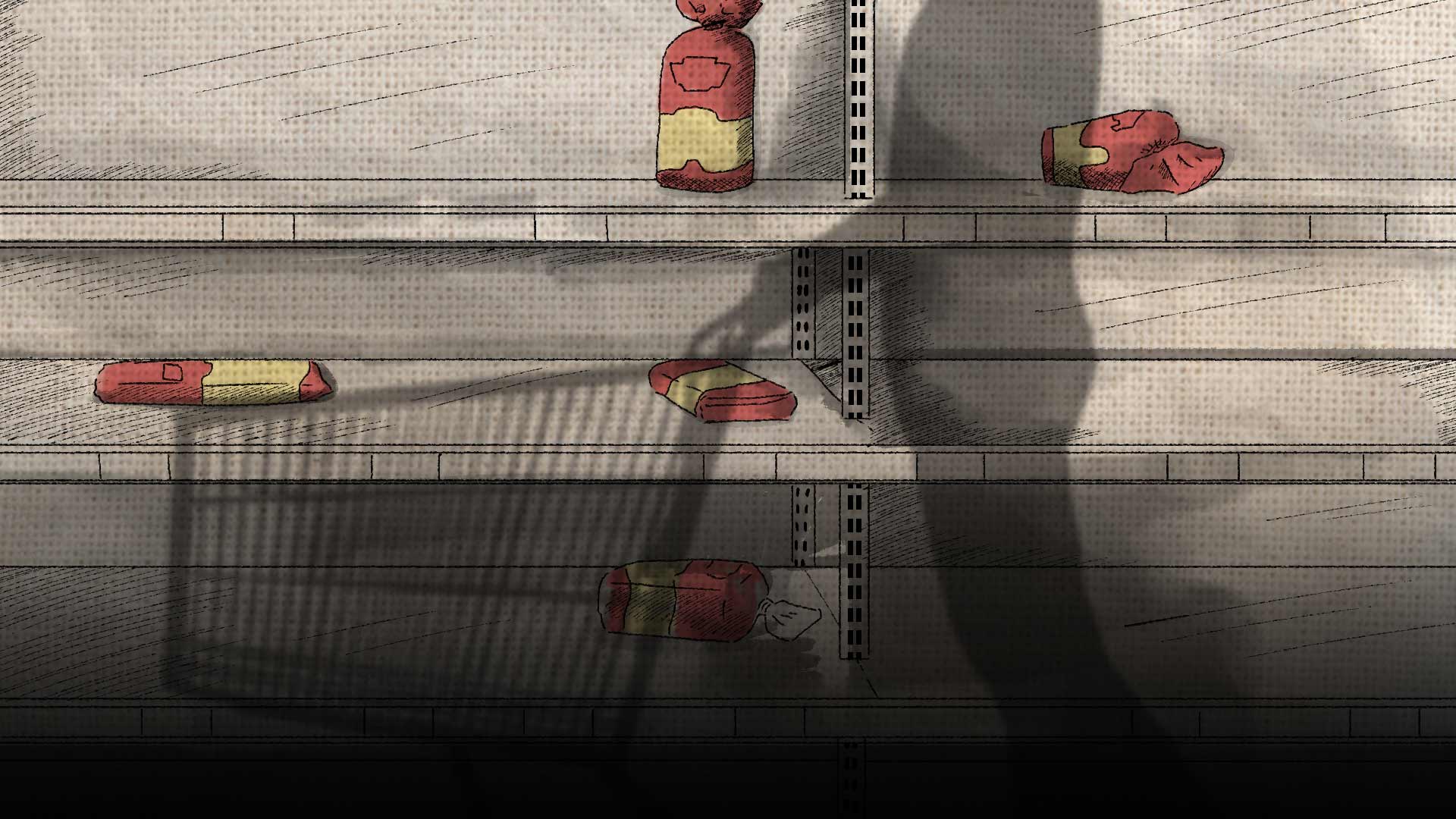

"As for flour and semolina, the shortage is obvious and the quantities we receive run out in record time, as the quantity I receive from the wholesaler each week does not exceed 30kg. This shortage has turned my work into a source of stress, so much so that I had a severe breakdown a few days ago and was no longer able to speak. Today's artisans seem to think that I am playing favourites by selling my products", Moez adds.

Does the presidential decree put an end to the shortage of subsidised products?

The Tunisian president's current communication policy focuses on the "war against the monopolies" to ensure the availability of basic food products in the country. As half of the imported grain comes from Ukraine and Russia, Tunisians feel that their food security has been compromised by the ongoing war.

In acknowledging the existence of speculation in the food markets, Kais Saied once again called for a new law to be enacted, intending to address the shortage of subsidised food, despite the fact that public institutions supervise market supply and control distribution channels.

The Ministry of Commerce claims that bakeries no longer want to sell subsidised bread, in favour of other types of bread. However, in a video promoting the success of the "war against monopoly" that was published by the Presidency of the Republic, the owner of a bakery in Hay El Khadra admits the persistent flour shortage.

What the Presidency of the Republic called "a war against monopoly" has resulted in a new presidential decree with unprecedentedly harsh sentences, ranging from 10 years to life imprisonment, and a fine of 500,000 dinars.

In addition, there is a 100,000 dinar fine for each person convicted of illegal speculation, defined by the decree as: "Any storage or retention of goods or merchandise aimed at causing a shortage or disruption of supplies at the market level, and any artificial increase or decrease in the prices of goods or merchandise or banknotes directly or indirectly or through intermediaries or the use of electronic means or any other fraudulent means."

The results are still unclear. Although the authorities have confirmed that thousands of tonnes of subsidised goods have been seized, only a few hundred of these are for sale. "I don't have an exact figure for the total quantity seized, but it amounts to thousands of tons, and remains with the Ministry of Commerce, which has delayed selling it", says Haithem Zaned, the official spokesman for the Tunisian customs.

He continues: "The first sale announcement was presented between March 16 and 18, 2022 and consisted of 60 tonnes of subsidised goods, namely couscous, pasta, semolina and flour, but the administration did not receive any bids, due to the lack of sufficient time to inform the traders."

"On the other hand, the sale was made during the following round between March 18 and 21, 2022 and consisted of 10 tonnes destined for Greater Tunis. As for the other two offers, the first was announced on March 21 and was extended until March 28 due to the strike of the Tunisian postal services. The sales amount consisted of 6.4 tonnes in Monastir and 108 tonnes in Tunis, with 334 bottles of subsidised oil", Zaned explains.

Apart from the sale, Zaned specifies that the confiscated quantities will also be put to use. They will be entrusted to the Tunisian Union of Social Solidarity, to be distributed to retirement homes and people without financial support, with the possibility of distributing them during the month of Ramadan as social aid.

When asked about the confiscation method, Zaned said that most of the quantities held in customs were intended for smuggling, whereas cases involving the monopoly are the responsibility of the Ministry of Trade. He explains that the smuggled goods are mainly intended for Libya, and the confiscations were made at border crossings and during patrols in warehouses at the border.

How are subsidised grain products distributed?

"We are currently producing the same quantities of flour, semolina, pasta and couscous as last year. At the moment, we are transferring between 1,300 and 1,500 tonnes of semolina to the eight governorates every day, under the supervision of the Ministry of Trade", says Wadii Gharbi, president of the Chamber of Owners of Mills, Pasta- and Couscous Factories, in a statement to Tunisian national radio on March 10, 2022.

Gharbi believes that the shortage is due to unjustified demand and the tendency of citizens to store semolina and flour in particular. As a result, quantities are running out in record time. "During this period, we have supplied the most important areas with more than 20% of flour and more than 40% of semolina compared to last year", says the president of the Chamber.

National quantity of grain consumption (2018-2021)

Source : National Gran Board

"During the month of Ramadan, bakeries are supplied with the necessary and usual quantities of flour and are able to provide bread without the slightest deficiency", the president of the Chamber of Bakery Owners, Mohammed Bouaanen, told inkyfada.

As for the long queues in front of bakeries on the first day of Ramadan, Bouaanan explains that people want to buy more bread for fear of running out. He confirms that production is currently at its usual rate, and that the quantities of bread prepared the day before have exceeded the quantities purchased.

Data from the National Grain Board website shows a drop of about seven thousand tonnes of grain sold in 2021 compared to 2020. However, the website does not have any data for the first quarter of 2022. Inkyfada tried to obtain these figures from the Ministry of Agriculture and the Director of Agricultural Production, Abdelfattah Saïd, but the requests were ignored and put on hold, while the Grain Board did not respond to our attempted email correspondence.

The enriched grain products are: pasta, couscous, semolina and flour. Production is carried out by the mills during the first processing of hard and soft wheat, and then by marketing.

Previously, private collectors and cooperative companies who were active in the grain and seed sector collected the local grain harvest. These days, the National Grain Board is responsible for supervising, organising and monitoring the collection operations, as well as receiving, storing and selling all of the grain collected by the private companies.

Distribution routes of grain products,

from post-production to consumption:

On the other hand, the Grain Board monopolises importation of hard and soft wheat. "To cover these needs, grain imports are carried out through restricted international bids launched when the feasibility of the purchase is validated. The Grain Board determines its requests based on the price of grain on the international markets and the stock supply", as stated on the website of the National Grain Board.

The Board organises the transfer of local grain from production areas to consumption areas. As for the imported grain, the Board is in charge of transferring it from the port silos (Bizerte, Rades, Gabes) to the consumption areas, in order to either store it in central silos or sell it.

The Board sells hard and soft wheat to the mills according to a monthly schedule established by a committee representing the Grain Board and the Chamber of Mill Owners.

Subsequently, this Chamber, which is part of the National Union of Industry and Commerce, distributes the shares of the private mills that are represented in the Chamber of Mill Owners.

These shares are calculated on the basis of the previous year's shares, which the rentier-economy-fighting organisation "Alerte" considers to be a policy aimed at preventing small producers from increasing their production.

In a podcast on income in the grain and milling sector, the organisation "Alerte" states that out of the 23 mills in Tunisia, 13 are owned by five people. Alert claims that "the subsidy for grain transportation exceeding 30 km has favoured the centralisation of mills in the Sahel region."

Out of these 23 mills, 19 are along the coastal belt, including 9 in Greater Tunis, 4 in Sousse, 3 in Sfax and 3 in Gabes. These 19 mills constitute almost 80% of the national transfer capacity.

The black market hinders access to subsidised oil

Carrying a plastic bottle and an empty bag, a 50-year-old woman enters Moez Sheikh's grocery shop to buy a litre of subsidised vegetable oil. Moez claps his hands together and points to the empty oil crates, saying, "Don't ask for any more oil, because that is about the last thing you can get."

"The supply of subsidised oil is still very low. No matter how much we increase the quantities, they run out quickly. Today we have to wait one or two weeks, and we only get three or four crates of oil bottles through the wholesalers, with 80 or 90 customers a day. Although the crisis started a month and a half ago, it has only recently come to an end and only very partially", says Moez Cheikh.

He adds: "The subsidised oil is destined for restaurants and pastry and confectionery manufacturers who buy a crate of bottles for 30 dinars, while its price is 10.8 dinars. We, the retailers and grocers, decorate the market since we only get crumbs, while the rest goes to the black market under the domination of the middlemen, at the same time as the anti-monopoly campaign is underway."

The State delegates the task of supplying subsidised oil and supervising its distribution to the National Oil Board. The Board's role is to purchase the national need for subsidised vegetable oil, and to monitor the refining process with the refining facilities, adopting a price specified by the state.

The Board subsequently collects the refined oil to check that it meets the required specifications. The oil is then sold to canneries at a subsidised reference price, while ensuring a steady supply of vegetable oils to all regions of the country.

Distribution of subsidised vegetable oil,

from post-production to consumption:

Inkyfada contacted the acting director of the Oil Board, Abdelfattah Said, and despite his initial willingness to discuss the role of the Board and the reasons behind the lack of public access to their products, he subsequently ignored all further attempts to communicate.

According to a report published by the Oil Board for the period of 2017-2018, the quantities of subsidised oil that are purchased annually amount to about 170 thousand tonnes, divided between 100 thousand tonnes of imports and 70 thousand tonnes of local purchases. Meanwhile, the decree of the finance law for the year 2022 reveals that the funds allocated for the subsidy of vegetable oils amount to 480 million dinars, noting that "the specific quantitative shares for canned food were revised from 14,053 tonnes to 13,348 tonnes per month in July 2017."

How are commodity subsidies managed in Tunisia?

The commodity subsidy policy dates back to the 1940s, when the International Monetary Fund was established by the Supreme Ordinance of June 28, 1945. This was followed by other ordinances that built the current legislative framework, and the General Compensation Fund is now supervised by the Commodity Compensation Unit in the Ministry of Finance.

According to the recent decree of the financial law, 3771 million dinars have been allocated to commodity subsidies this year, compared to the 2200 million dinars in 2021. The subsidy for grains was set at 3025 million dinars, pasta and couscous 86 million dinars, and vegetable oil 480 million dinars, while 160 million dinars were allocated to milk, and 10 million dinars to sugar and school paper.

The obvious price difference between subsidised and non-subsidised food products makes them prone to speculation and misallocation towards non-domestic consumption.

In this context, the last published regulations on trade of subsidised products date back to December 2020. The then Minister of Trade and Export Development, Mohamed Boussaid, issued a decision on the approval of a set of specifications regulating the trade of subsidised commodities by traders of raw materials.

These specifications regulate the distribution of the products. Chapter six stipulates that wholesalers are obliged to sell the subsidised products exclusively for the benefit of retail traders, in reasonable quantities, and compatible with the scale of their business.

The book further stipulates that the sale of commodities for industrial or other purposes is prohibited.

At the same time, wholesalers are obliged to keep a register of purchases and sales numbered and signed by the Regional Trade Administration, or to register all purchases and sales of subsidised basic materials, conducted on a daily and periodic basis in the information systems related to the monitoring of the import of these materials, and supervised by the Ministry of Trade.

The booklet also stresses the need to submit these registers to the regional trade administration on a monthly basis.

According to the regulatory laws, the Ministry of Trade, via the Commodity Clearing Unit, has an overview of the stocks and quantities distributed for all food products distributed on the market. However, despite the fact that figures and reports show the availability of stocks, it is almost impossible to obtain a packet of flour or a bottle of subsidised oil today.