Part one: Tunis

September 2016

There had been a warning signal. At the beginning of the Libyan Revolution in March 2011, a young woman named Iman Al Obeidi bursts into the Rixos hotel and interrupts a gathering between Libyan government representatives and the international press corps. She shouts across the room before being violently dragged away: she had been detained by the Gadaffi regime, gang-raped, and has the marks to show. Her pleas are drowned out, and the government claims that she is a drunken prostitute. But something was set in motion, and she is eventually able to seek refuge in the United States.

Thanks to her desperate act, the story gets out. Very quickly, the rumor of rape committed by the dictator’s army begins to spread. The international community is alarmed and calls for an investigation. At the end of April 2011, the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Luis Moreno Ocampo, promises to take action. And then? The story dissipates.

The news networks are busy covering the NATO air strikes, Gaddafi’s overthrow, and Libya’s inevitable transition to democracy. Then, they move on to the horrors in Syria and the tempestuous flow of migrants to Europe; meanwhile, Libya fades from the headlines.

Today, the country is a ticking time-bomb. There are two governments without real powers, there is no state, and hundreds of militias routinely kidnap, pillage, torture, and, as the Libyans know, rape. But up until now, no one has been able to prove the use of rape as a weapon of war in Libya.

October 2016

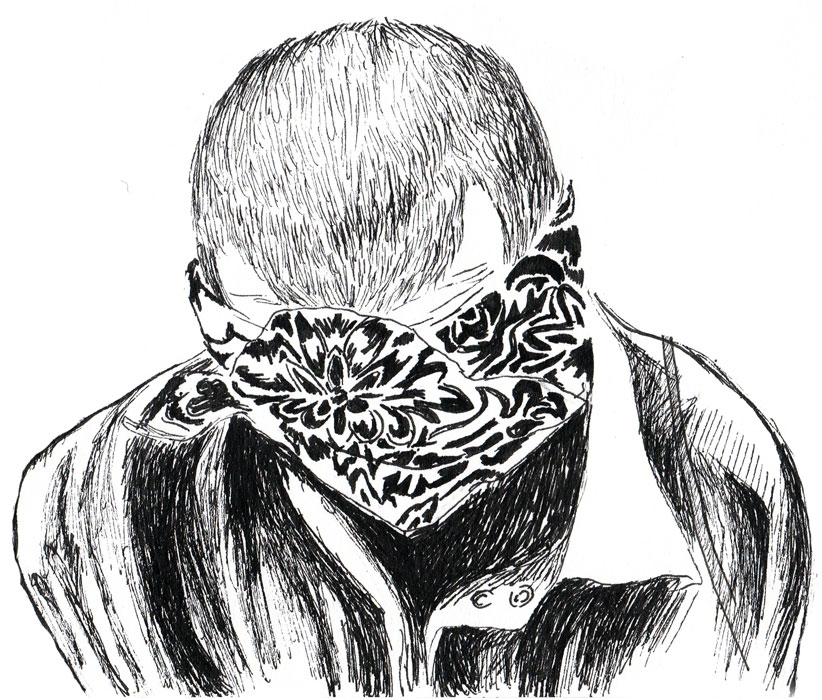

For a long time, Yassine preferred to hide behind a computer screen. Online, I only ever saw his silhouette, rigid against the dim lighting. He never said much. One day, he agreed to come to Tunis. But just crossing the border wouldn’t free him from fear. From the moment he arrived, he seemed to be searching for a way out. But he explains to me that he is here to help other victims who need a safe place to seek treatment. “ The victims are keeping quiet, terrorized by the idea of being denounced, of losing everything . . . family, friends, work . . . trust a doctor? No, it’s too risky,” Yassine says in a nervous voice.

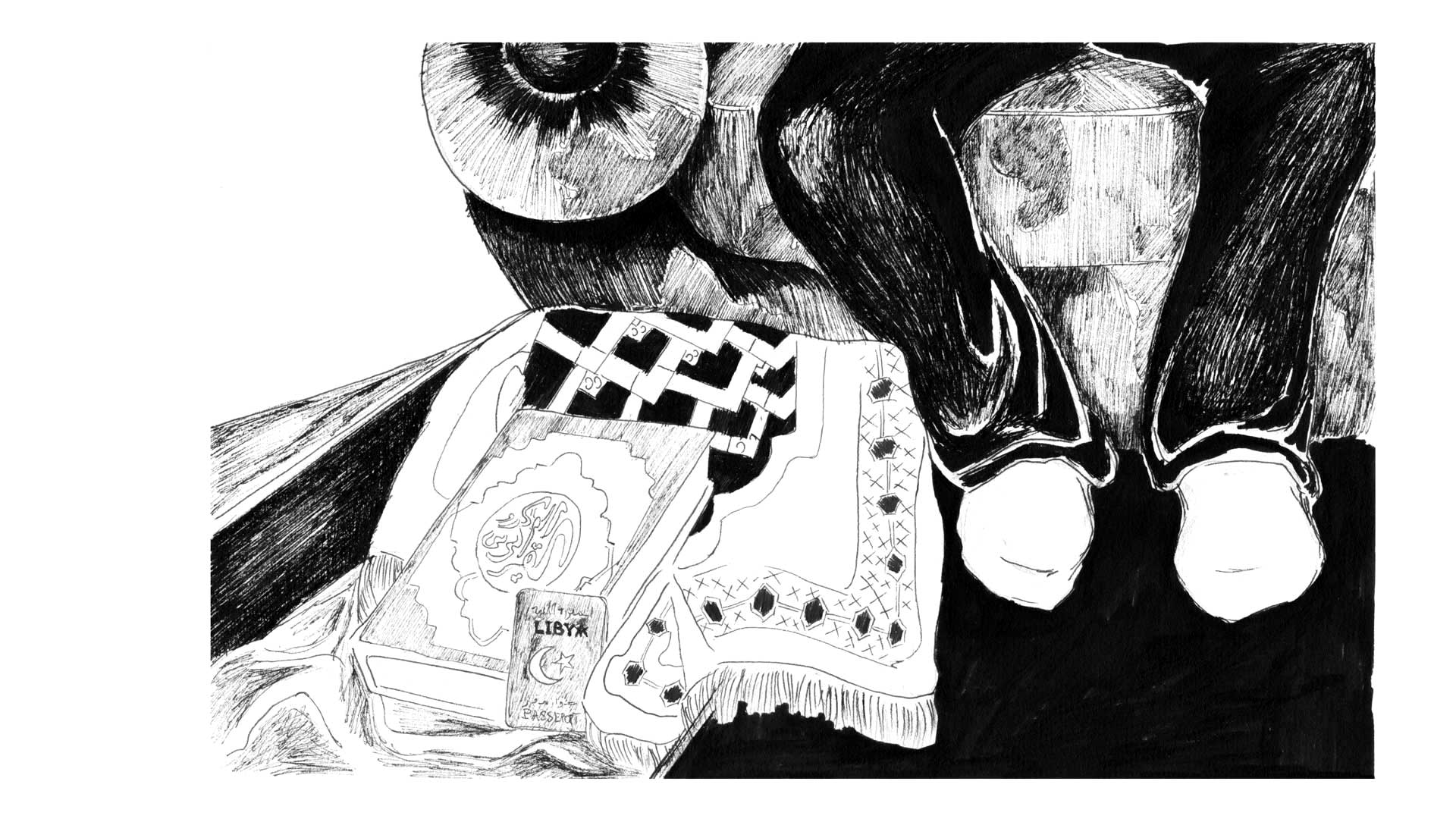

We arrived to a nondescript, two-room apartment in Tunis, close to the airport. Yassine takes two sedatives; his movements are heavy. He slowly opens his suitcase, takes out a Quran, a Libyan passport, and a prayer rug. Unpacking his suitcase seems like a burden. Yassine takes a seat on a peeling, fake leather chair. “ You can offer millions to the [female] victims, so that they will testify in court . . . they would tell you ‘never.’ I prefer to remain hidden.” Yassine notices his switch from “them” to “I;” he jumps in his chair and looks at me, terrified.

How can I forget that look? Yassine was one of the victims.

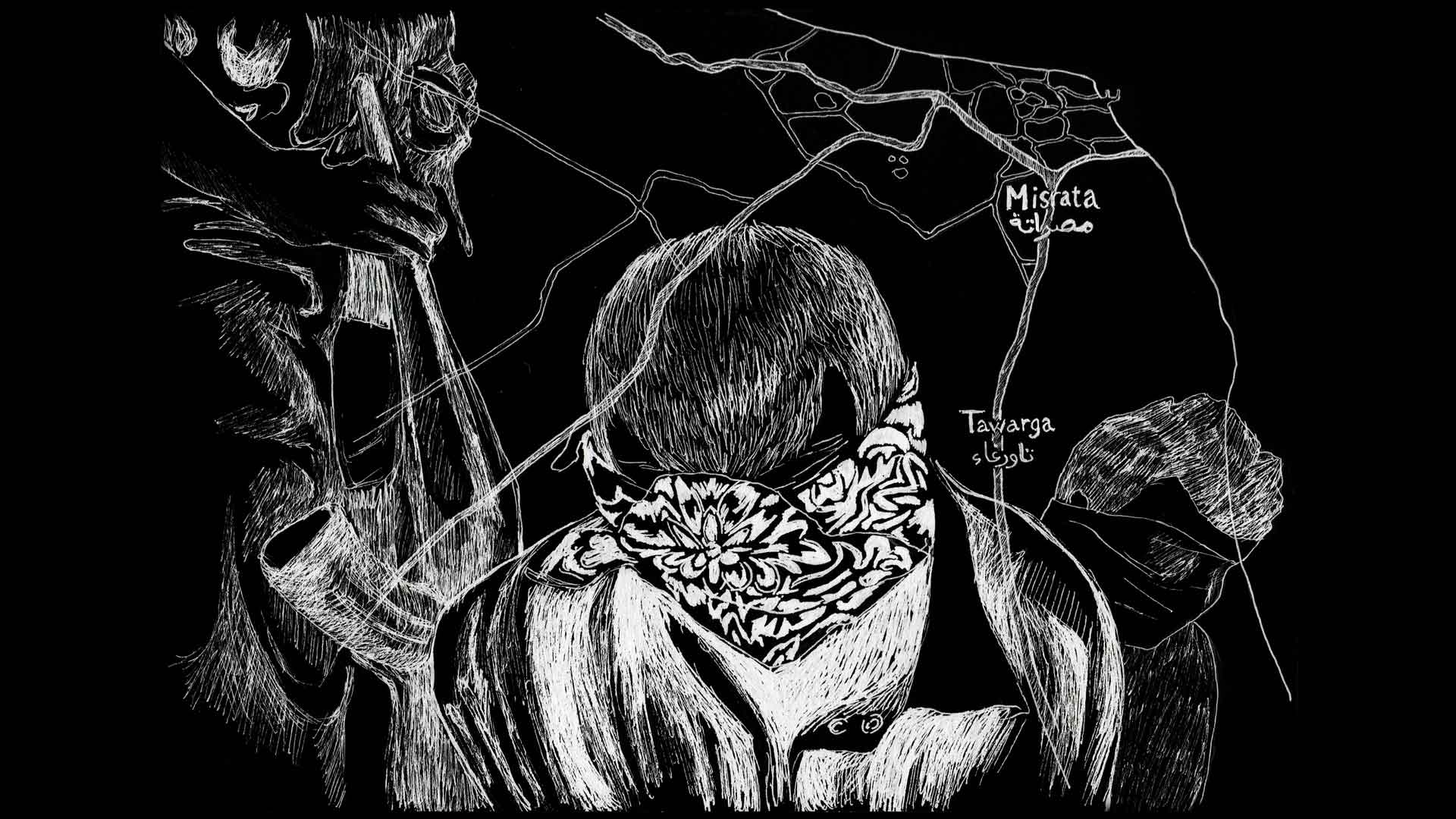

There is not much to recount from his life before. Yassine lived a simple life in the south of Misrata. On March 29th, 2011, after a month of being under siege, the west of the city is infiltrated by fighters loyal to the Gadaffi regime. The soldiers go door to door, forcing their way in. That night, Yassine tries to escape with the married couple next door. They try to reach a back road, but they are blocked by about thirty armed men, “ some were wearing official uniforms, others were mercenaries from Tawargha. I am sure of this,” insists Yassine.

Misrata vs. Tawargha: The first counter-revolutionary actions revived historical tribal rivalries. Misrata is a rich and independent coastal city. Tawargha is situated 35 kilometers south of Misrata and is the homeland of the tribe of the same name, Tawarghi. During the war, Gadaffi used the city as a support base and some Twarghi as henchmen. Misrata never forgave them. Misrata contre Tawargha. Les premières manœuvres contre-révolutionnaires ravivent les rivalités tribales libyennes. Misrata est une cité côtière, riche, indépendante. Située 35 km plus au sud, Tawargha est la ville-mère de la tribu homonyme, les Tawarghi. Pendant la guerre, Kadhafi utilise la ville comme base arrière, et certains Tawarghi comme hommes de main. Misrata n'a jamais pardonné.

Yassine continues: “ The men were tied up and hooded. They pissed on us, like dogs.” He ends up in a house-turned-prison in the city of Tawargha.

“ One room was dedicated to torture. We heard the cries of others . . . they were targeting their private parts . . .”

His voice breaks. “ I understood what they were doing . . .” A tear falls down his cheek. “ The hardest part is to stay alive without being able to forget what happened. They knew that.” Yassine freezes. I call his name softly. He cries, without moving, without making a sound. He is no longer with us. After what seems to be an eternity, Yassine stands up and goes to lie on his bed; he immediately falls asleep.

Two days later, Yassine starts again. “ Imagine that they tell you ‘we will kill your brother’ or ‘ we will rape your brother.’ What would be worse? The response: ‘we raped your brother.’” I walk alongside Yassine as he roams the streets of Tunis. He tells me of his many moves from one part of Misrata to another, then from one city to another. He speaks of his nightmares, his sleepless nights, and how he is suffering because he cannot have another child. More than anything else, he tells me about the shame that torments him.

“ Even here, I have the impression that everyone sees me for the defiled man that I have become.”

Yassine struggles to walk in a straight line; he needs to see a doctor. I offer to accompany him. Yassine stops in his tracks. To show himself, in front of a man? The next day, Yassine disappears.

Before disappearing, Yassine gave me the phone number of Fatma, his old neighbor with whom he tried to escape. They haven’t spoken since that fateful night in March 2011. Fatma left Misrata many years ago. When I contacted her, she asked to meet in Sidi Bou Said, in Tunis’ seaside suburbs. She’s still young, with friendly features and an empty look in her eyes. She lights a thin cigarette and sighs. “ It’s like that, war. And I didn’t know anything about it.”

Fatma hesitates to begin, but she eventually jumps in. “ My neighbor was raped the day before. The next day, we fled . . . it was too late.” Her hands tremble, and she begins to sob. Fatma and her husband had been stopped by a group of about ten people, who she thinks were from Tawargha. She and her husband were separated and blindfolded. She never saw him again. “They raped me and threw me to the side of a road. I didn’t learn of my husband’s death until May 2011.” Fatma then fled Libya and sought refuge across the border in a small Tunisian town.

Six years later, she can barely walk, but she makes it on her own. She smokes cigarettes the whole day through. There is no help, no support system for Libyan victims in Tunisia. There are only a few private clinics where the richer victims go to be treated discreetly.

NovembeR 2016

It was a dark night in Tunis. The air felt heavy, as if a storm was on the way. Over many hours, Abderrahmane explains to me why no one has been willing to talk about the incessant raping being committed in Libya. Abderrahmane is a human rights activist from the east of Libya; his hair and beard are cut short. He tells me that many people were raped during the Revolution, and in the aftermath, the winners continued to take revenge.

“ It is an unending cycle: violence without an end.”

When he arrived to Tunis, he joined a group of exiles trying to gather evidence on the crimes being overlooked in Libya, rape being one of them. The office doors swing open and Mahmoud enters. His shoulders are wide, he is slightly overweight, and his smile is full. Mahmoud is Libyan, from the Tawarghi tribe. He is a grassroots activist. “ A man from the East and a Tawarghi who are friends, you see, there is still hope for Libya,” Mahmoud says with a smile.

He then sits down and takes out his computer to show a video. It shows a black man, exhausted and tied up. A voice shouts, “ Dirty Tawarghi dog!” Mahmoud has the date: “ October 2011. They raped him with the barrel of a gun. I managed to find him. But when I wanted to add that he was raped to the file, he told me, ‘No. You can write everything except for that.’” In another video, we see two young men from Tawargha, their hands on their heads. “ They raped two brothers. The elder died, the younger one committed suicide.”

Abderrahmane gets emotional and forcefully puts out his cigarette. “ The problem, Mahmoud, is that they always tell you ‘Ystahal,’ serves you right! You got raped, you asked for it, ‘Ystahal!’ . . . it will take 50 years to get rid of this problem.”

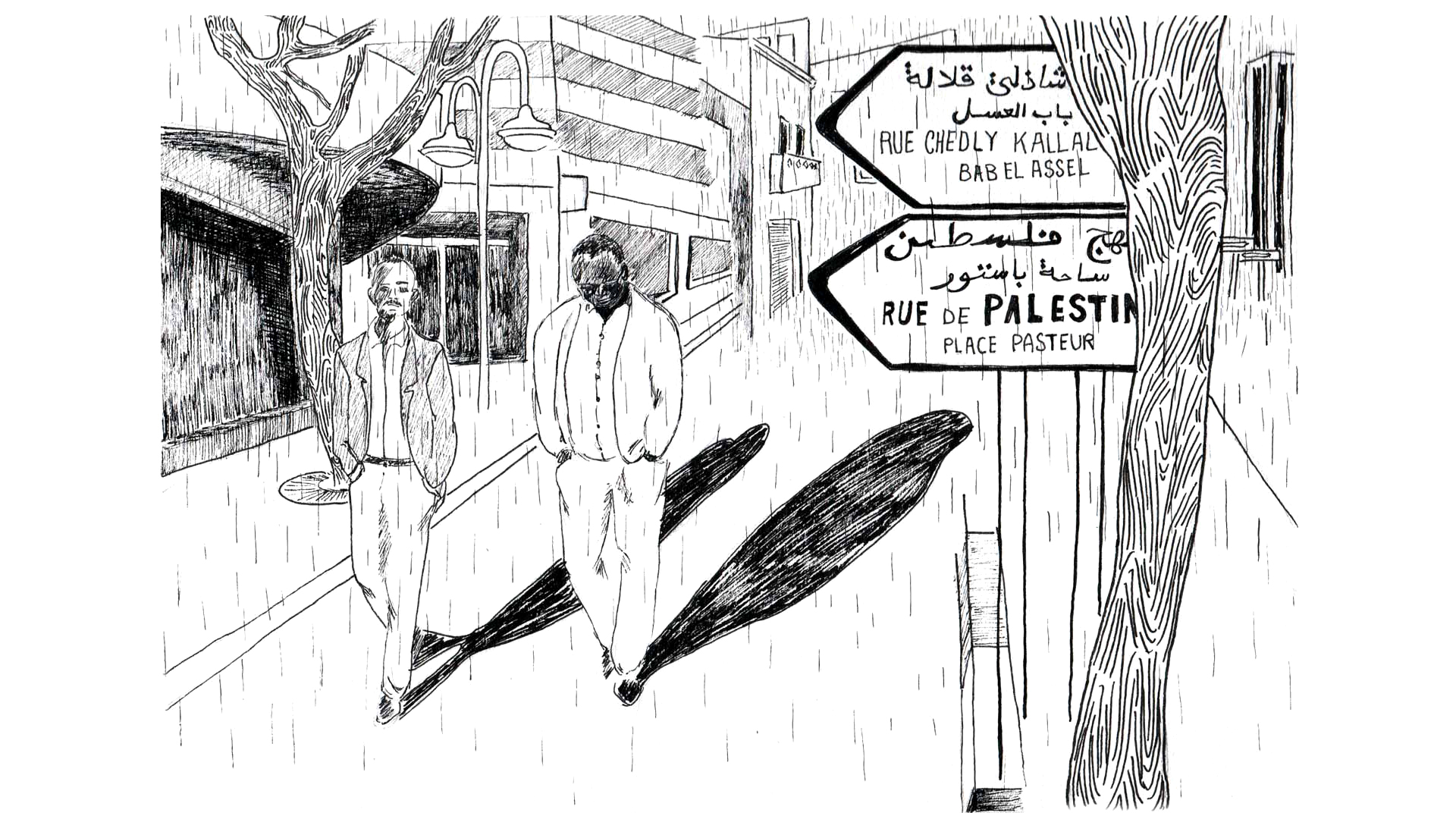

The stigma of rape traps victims in shame. To speak of it is to dishonor your family, a community that might span generations. Even if you do, what state is the Libyan judicial system in to help? It’s been almost three years now since Mahmoud and Abderrahmane began collecting evidence of abuses committed in post-revolution Libya: kidnappings, extortions, disappearances, torture, and of course, sexual violence. Three years of working alone, without any outside help. The two friends walk through the empty streets of Tunis. It begins to rain. They leave each other without a word.

Now in the taxi, Mahmoud hums a Libyan song, as he tends to do when anxious. “ Bombs take down people without them even realizing it. But rape is a weapon that cannot be seen. It is necessary that victims speak out so we can understand how this weapon is used and who is behind it. We are too few to ask ourselves these questions.”

In early 2014, unidentified militias assassinate around one hundred judges and activists. Abderrahmane and Mahmoud survive the massacre and flee the country in May. Three years later, the two have just a handful of helpers in Tunisia — exiled judges, lawyers, prosecutors, and activists — and only a few more still in Libya.

Abderrahmane moves often, out of fear of being spotted, kidnapped, and punished for having spoken out. “ You think that it is easy for an Arab man to speak . . . about rape,” he hesitates, lowering his voice while lighting a cigarette. “ We are convinced that torture and rape are still used as weapons of war in Libya. But we do not even have enough evidence to prove what happened in 2011! We still don’t know the extent of those crimes.”

Leaning on the balcony facing a vacant lot, he continues, “ You cannot imagine the hell that we are experiencing in Libya. Militias are everywhere, they control everything . . .” His eyes search for the horizon in the distance. “ You see this road? In Libya, it would be a demarcation line between zones controlled by different militias. There would be checkpoints every five hundred meters and prisons everywhere, everywhere! Everything is transformed into a prison there. An apartment, a cellar . . . even a simple bathroom!”

Mahmoud shares a modest three-room apartment with two other exiles. He became an activist out of necessity and can no longer turn back. The fridge is empty; the bed is made. On the floor lies an open suitcase with some shirts, a comb, a hairbrush . . . the simple accessories of a life on the move.

“ In Tunis, victims feel more free to speak. But when you try to document rape in their files, they immediately disappear.”

To guarantee silence and cover up their crimes, the perpetrators film the rapes. Mahmoud shows me his pile of documents mostly comprised of medical files and testimonies that speak of kidnapping and torture happening consistently, all across Libya. “ I’ve met maybe 300, 350 victims. Not one of their statements is complete. It’s become crazy. Everything else can be documented, except for [rape]!”

DEcembeR 2016

Samir was roaming around the streets of Tunis, homeless. He drinks coffee, speaks very little, and doesn’t stay in the same place for too long. Samir was a soldier in Gadaffi’s army and took part in the siege of Misrata. “ It made me crazy . . . I saw things.”

“ The guys came in with the father tied up. They raped his daughter and his wife and said, ‘You wanted the Revolution? Here, take it, your Revolution.’”

Who were the rapists? Samir shakes his head. “ I will not tell you of the battalion. A soldier always obeys his superiors. Do you understand?” They had a name for this. “ Forced houses:” the metonym for rape committed under orders during the Revolution.

“ After the end of the war, what the revolutionaries did to us was a thousand times worse,” Samir continues. He was kidnapped twice, imprisoned for eight months, and tortured by his jailers. “ They said, ‘You, Gadaffi loyalists, you raped? Eh, now it is our turn.’” Samir takes a drag of his cigarette.

“ Now it is too late for Libya . . . You understand? You rape, you break everything, you cannot reconstruct a country any more, a state.”

Rape was one of the key weapons used to destroy the country: the unspeakable “ thing” that stands in the way of reconciliation.

JanUARY 2017

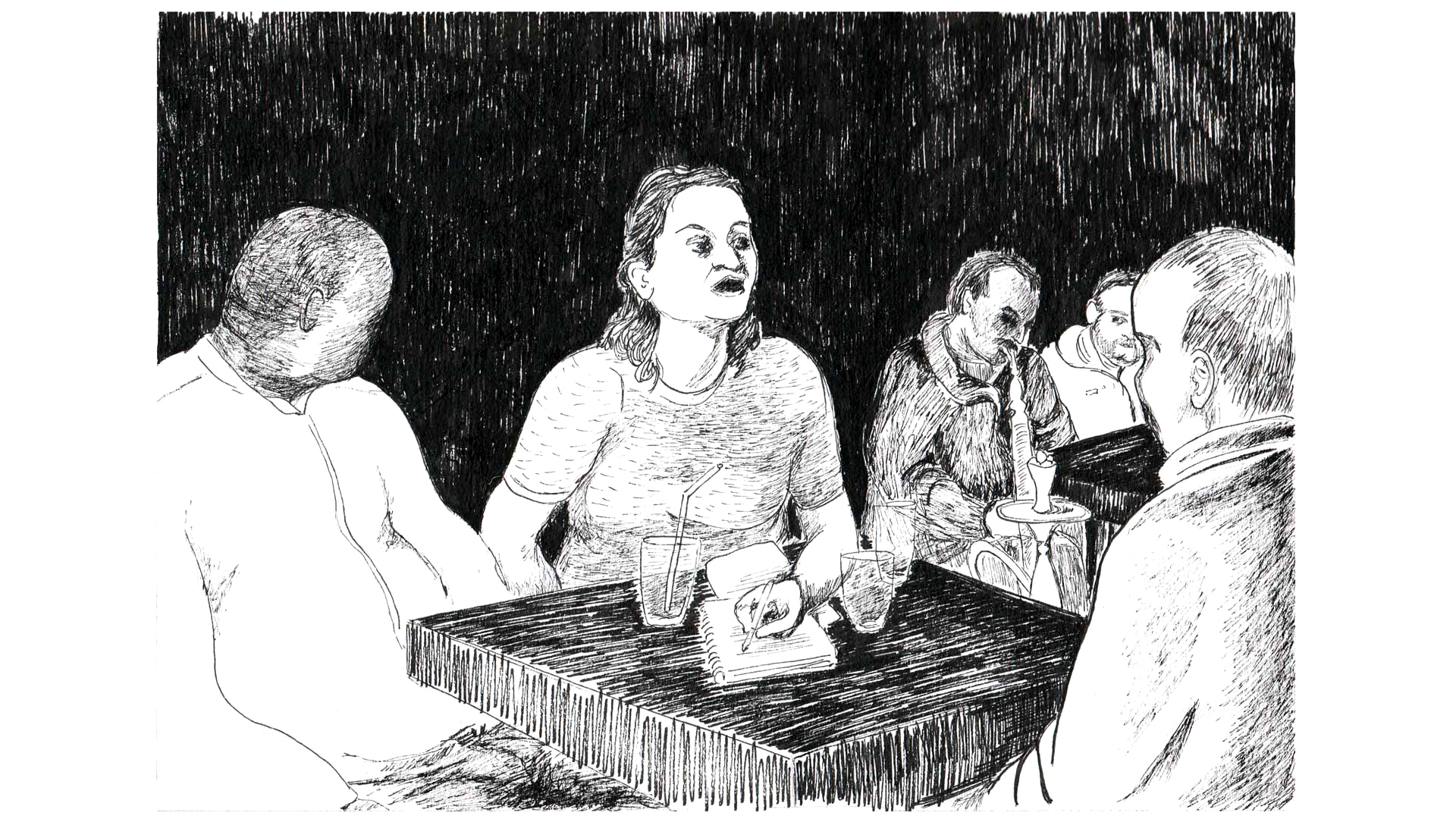

By January 2017, Mahmoud and Abderrahmane have collected hundreds of pieces of evidence, but they still don’t have a legally admissible file. The investigation is at a standstill. But in Tunis, they are fortunate to meet one of the only people who understands the challenges they face and the goals they’re trying to achieve: Céline Bardet. In 2013, when the Libyan Minister of Justice, Saleh El Marghani, decides to draft a law that would protect victims of rape, it’s this expert that he calls upon.

Known for her outspokenness and tenacity, Céline Bardet created a war crimes unit in Brcko, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and sent dozens of criminals to prison, some of whom were found guilty of using rape as a weapon of war. The Minister knew of her impressive work, but he underestimated the magnitude of violence taking place within the post-revolution chaos. The law would never be applied. In the meantime, Céline establishes an NGO, WWoW, that works to eradicate sexual violence in conflict zones.

The activists based in Tunis finally arrange to present their findings to Céline. She enters the café, takes a seat, and starts to take notes.

“ Rape and war have always gone together,” explains Céline Bardet.

“ The reward for the winners, the loot of the warriors . . . it goes back to the abduction of the Sabines. But there was a turning point in the 1990s that no one fully appreciated. This is where we, the international criminal investigators, understood that rape has become a preferred weapon of war. Because it is cheap to deploy, it doesn’t leave bodies behind, and yet it destroys a nation over several generations. It’s the perfect crime.”

A few days later, Céline, Abderrahmane, and Mahmoud meet again in an office provided to them by a friend. Céline gets right to the point: “ In each one of your documents, specify the place, right when it happened. Afterwards, we cross check everything and identify the legal context of the crime. If you don’t do this, you’ll be demolished in court.” Céline mentions the case of Jean-Claude Bemba, the vice-president of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the only criminal convicted of using rape as a weapon of war by the ICC “ for having given the order, without participating.” Abderrahmane can’t hold in his excitement: “ it’s similar to the cases we have too!” Céline quickly responds, “ Then we need to obtain full testimonies, if possible. It’s urgent.” Céline Bardet leaves Tunis, but hopeful feelings remain.

FEBRUARY 2017

The month of February brings torrential rain; the sewers overflow into the flooded streets. Mahmoud is agitated; a victim whom he had been following for weeks just left Libya. He was a resident of Zliten, a former Gadaffi stronghold.

We ring the doorbell and the door opens. Mahmoud gives a long embrace to the figure whom he only knew by voice up until that moment. Ahmed is thin, his face sunken. He was kidnapped in 2012 and just recently made it out of the terrible Tomina prison. He wants to speak out about the horrors he faced there. “ There, they isolate you and subjugate you . . . ‘Subjugate men,’ that’s their expression. To crush you, so that you never lift your head again.” Mahmoud listens attentively.

“ Everyday they take a broom and fix it to the wall. If you want to eat, you have to take off your pants and back up onto the broomstick . . . and you don’t get it out until the jailer sees blood running . . . No one escapes this. Imagine to what point you feel destroyed.”

Mahmoud asks in a calm voice, “ When was this?” “ From 2012 until 2016 . . . the chief warden was called Issa Issa, from the Chaklaoun family. He smelled of rose water. When I smelled it, I knew that I was about to be raped,” Ahmed paused and then added, “ When he died, his brother, Tarek, succeeded him. He was even more violent.”

Mahmoud writes down the names and dates. “ Were there women?” Ahmed changes his position with a grimace. He suffers. “ No, we were 450 men. I am sure of that number because in prison, I had kitchen duty; every day I counted the cutlery that I washed.” Ahmed continues to list torture methods, each more sadistic than the last. Then there was a pause. “ There was a black man, a migrant. In the evening, they threw him into one of the cells.”

“ They said, ‘You, rape this man. If you don’t you are dead.’ If he didn’t rape, they would massacre him.”

Silence takes over the room. Mahmoud collects himself and examines the papers that Ahmed presented: a blood test, an X-ray of his lungs . . . “ But you were never examined for rape?” asks Mahmoud. Ahmed lowers his head. It is still too soon for him to show his suffering.

What Ahmed reveals is shocking: contemporary Libya has given birth to a new monster: a system in which men have become the targets of rape as a weapon of war. And migrants are used as physical instruments of retaliation.

MarCH 2017

Hosni Lahmar waits in front of his clinic. This emergency doctor has received many Libyan patients. Ahmed, accompanied by Mahmoud, has finally come to be examined. He sits in front of the doctor, his head lowered.

“ I am afraid that I contracted terrible diseases.”

The doctor looks at him calmly. “ Was there violence?” “ Yes.” The doctor asks him gently, “ Can I see?” Ahmed undresses himself, turns around, and lets himself be examined, without a word. After about 40 minutes, doctor Lahmar writes, “ Male, 45 years old, raped multiple times, with foreign objects. Incontinence and STDs. Anal fissures.” He hands a paper to Ahmed. “ Be stronger than your torturers, don’t let yourself break down, Ahmed. And above all else, don’t be ashamed . . . this is the key to recovering.”

APril 2017

In the weeks following the visit to the doctor, Mahmoud takes on more meetings. Céline is back, and she’s impressed. Finally there’s a key witness, capable of identifying his torturers and his fellow detainees. “ Systematic violations in a precise place, at different times. This time, we have something solid,” she announces enthusiastically.

Mahmoud is silent for a moment before announcing, “ I have another victim. He described the same torture techniques as Ahmed, but in another prison.” Céline freezes. So Mahmoud continues: torture using bottles with serrated tops on which prisoners were forced to sit, until the torturer would tear it out; the tire through which detainees would stick their bottoms, the targets of rocket launchers of different sizes; and, of course, the stick fixed to the wall — the obligatory passage to gain access to food.

In the taxi back, Céline confides, barely holding back tears,

“ I’ve never seen anything like this.”

The team was building a solid case. They had precise facts, cases showing similar torture techniques, and a formal medical examination from a brave man willing to tell the whole truth in his testimony. For Céline Bardet, this could be enough proof to start unearthing the systems behind the widespread use of rape in Libya. Ahmed’s arrival propelled the investigation in the right direction. There was no other choice but for the team to go to Libya.

PART TWO :

LIBYA

APril 2017

Libya is the modern embodiment of omertà — a code of silence. Six years of deafening silence have nearly buried an astonishingly vast and violent legacy of war crimes. ” If a militia stops me, the first thing that I will suffer is rape. So that I will keep quiet forever and drop this investigation.”

In early April, Mahmoud prepares to return to Libya to gather more evidence. But in Libya, militias are hiding, keeping watch . . . while the victims keep quiet. Mahmoud sighs. “ This cursed silence . . . how did we get here?”

At the other end of Tunis, another Libyan man asks himself the same question. A veteran of the Revolution, this man goes by his real name, Rabei Dahan, as well as his war name, “ Rio.” In January 2011, he and his four brothers joined the Katiba brigade of Tripoli.

Disgusted by the violence, Rio decides to flee to Tunis and he becomes a whistleblower. As of now, he creates subversive animated videos that he diffuses via social media networks; the next will focus on rape as a weapon of war. “ We all prefer to tell ourselves that at best it’s a myth, at worst unfortunate collateral damage of war. To speak about rape in our society seems just as bad as rape itself. We must, however, come out of this darkness.”

According to Rio, the source of Libyan violence is rooted in the systematic use of torture and rape by the Gaddafi regime. “ Gaddafi created a culture of rape to terrorize people and create this omertà. In ordering his troops to rape, he knew what he was doing: rape calls for vengeance and starts a cycle of endless retaliation. By now it has been committed everywhere and by all parties in Libya, even by the revolutionaries. We had one Gaddafi . . . now we have thousands of them!”

Rio recovers his calm. “ The rape of women in conflict, it is an atrocity, but something to be expected. But when men are systematically targeted . . . then it doesn’t have anything to do with sexual urges. A raped man is no longer a man. He’s a subject. This system has a clear objective; rape changes all the political balances, the exercise of power.”

“ This crime is destroying the country. How can we reconstruct Libya if we continue to ignore rape? How can we break this code of silence?”

As in response to this cry for help, Fatou Bensouda, a prosecutor with the ICC known for her work against sexual violence in conflict, decides on April 24th, 2017 to make another move. In 2013, the ICC brought charges against Waled Thouali, the former director of internal security for the Gadaffi regime. During the Revolution in 2011, an officer ordered the first raids on major cities in Libya: Benghazi, Misrata, Sirte, Tripoli, Tajoura, and Tawargha.

Three years later, Fatou Bensouda decides to lift the seal and reveal the charges brought against the former head of Gaddafi’s “ secret police.” Waled is convicted of crimes against humanity and war crimes, having ordered acts of torture and rape.

Time was passing by. The group still needs to prove that rape is being used as a weapon of war throughout Libya, and by all militias — regardless of their tribal, political, or religious affiliations. To help the case move along, there was no choice but to leave for Libya.

MaY 2017

Tripoli is a dangerous city. Days engulfed in war are followed by days of eerie calm. Dozens of militias are active, taking the law into their own hands. Mahmoud lets me accompany him. The Metiga Tripoli airport, although closed several times since the beginning of the year, has been open since March. Mahmoud waits for me at the exit, accompanied by Mehdi, a former orthopedist who became a human rights activist.

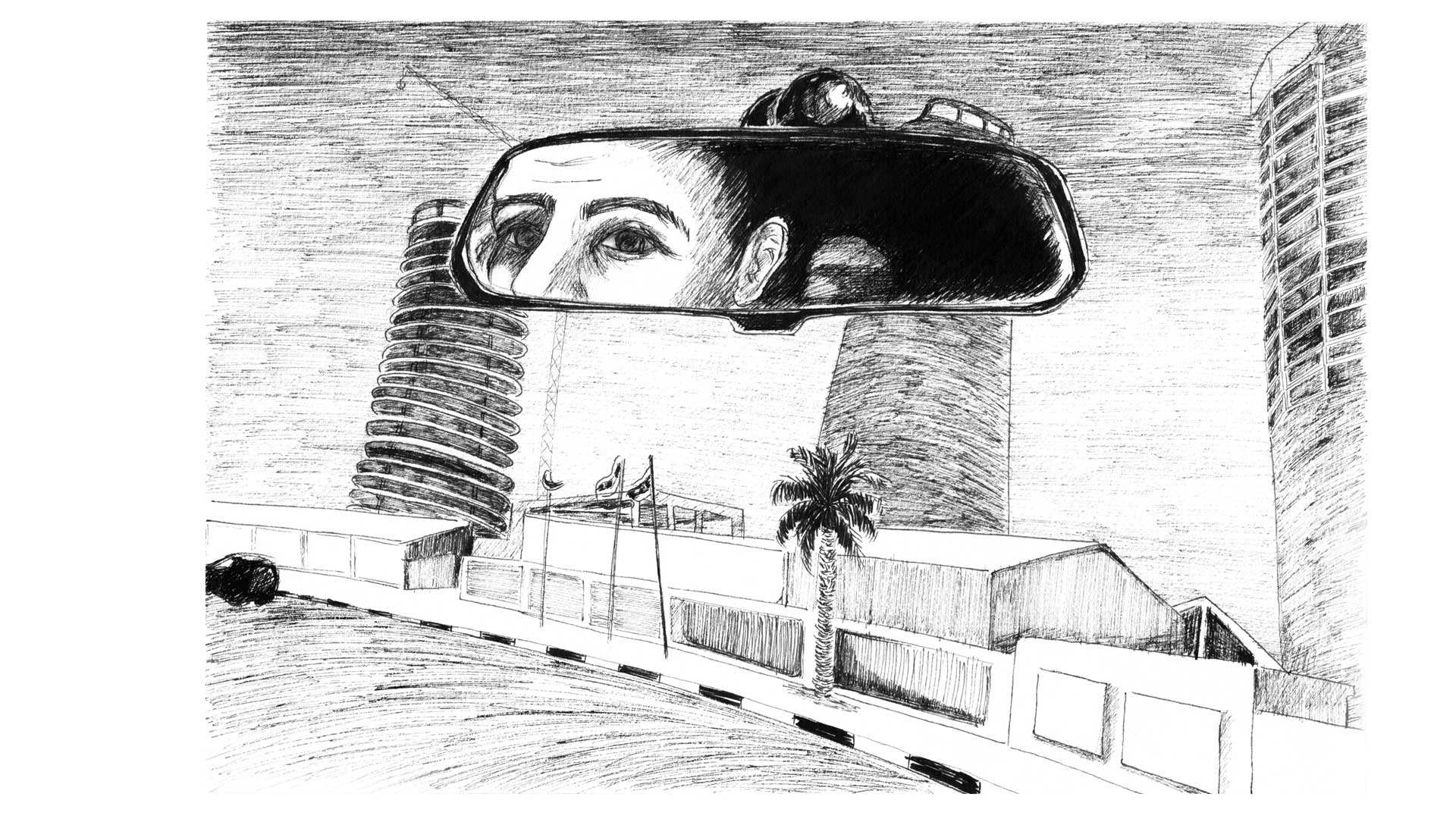

The car rolls west on Al-Shat road at full speed; the road continues all the way to the west of the city, with the sea keeping pace on the right. The car passes by neat lines of palm trees, small playgrounds, and restaurants open for business. At first glance, Tripoli seems normal. But on the side streets, Humvees and anti-aircraft rockets wait attentively, ready to cordon off the road and prepare for attack. Mahmoud is silent. Mehdi’s eyes are fixed on the rearview mirror; he heads south, zig-zagging so as to avoid checkpoints.

Their first stop is a friend’s office; they find Mouna,* an activist from the region of Zuwara, waiting patiently. Mouna looks at Mahmoud; she can finally put a face to the name. He jumps into his role. “ Did you think about protecting your documents?” “ Yes, I sent everything to the UN Office of Human Rights in North Africa . . . but I didn’t receive a response,” Mouna says with despair. Mahmoud comforts her and asks for the number of cases that she’s documented to date: she has dozens, maybe even a hundred. Mouna tells Mahmoud about a case of a former Gadaffi soldier who was taken, thrown into prison, and raped repeatedly. “ With a stick fixed to the wall?” asks Mahmoud. Mouna confirms, yes.

“ But the family begged me to stop everything; they were receiving death threats,” Mouna says while shaking her head.

She and Mahmoud are sure: there is a systematic use of rape against men held in militias’ clandestine jails. She adds, “ Even if they’re less in number, women are still the victims of rape, at any time. Recently, I took on a case of a 15 year old girl who was kidnapped by a militia on her way to school. Because her father didn’t pay the ransom, they kidnapped her two younger brothers. We have no news of them.”

Mahmoud writes down the name of the family and the dates. “ I also have several cases of mothers who were kidnapped, raped in the middle of the day, and then released. The worst is that they often know the rapist and are obliged to run into him on a daily basis.” The last time that Mouna tried to take evidence outside of Libya, three men intercepted her in a small street and put a knife to her neck. “ Whore, you are dirtying your country with your schemes!” The militiamen destroyed her passport. Mahmoud reassures her,

“ It will take time, but we will help you. I will take your documents out of the country and we will continue our work.”

The second stop is in the south of the city, several kilometers from the infamous Abu Salim high-security prison, where Gadaffi did away with his opponents. Mahmoud pushes open a gate and walks towards a prefabricated building. The door opens; three women and two men usher them in. This small group tries to keep track of kidnappings, detentions, and disappearances. One of the men, called Mahjoub, opens up a wardrobe; 650 alphabetically arranged folders loom over them. Mahmoud takes a seat and begins to read over the summary document that Mahjoub handed him. There’s no time to waste.

“ Is this the list of the missing?” “ Yes,” responds Mahjoub, “ we classify them by type: those who were kidnapped, those who disappeared in prison, and so on.” Mahmoud smiles. “ It’s excellent work. On the other hand, look at the file of this former detainee at the Tomina prison. There, it is certain he was raped. But there is nothing on this in the file?” Mahjoub defends himself: “ For the formerly imprisoned, it was urgent to register them first . . . it takes time.” Mehdi intervenes: “ With 650 files, you can’t keep track of everything. If you think that the man was raped, I advise you to add a note at the end of the page . . . for example, you write the word ‘Sinai’ as a code for rape. That way, when you see that person again, you know what you’re trying to learn.” Mahjoub nods. “ You are right . . . but Ali, this man who was tortured in Tomina, I saw him. It devastated me. What they did to him, you wouldn’t wish that upon your worst enemy.”

By the end of the first day, Mahmoud had collected a large pile of evidence to examine . . . evidence with dates, places, and specific names.

The majority of the new cases involved Tawarghi people, the tribe that Mahmoud comes from and also from where Gadaffi drew his henchmen. During the sieges of major rebel cities, most notably Misrata, Tawarghi men supported the troops loyal to Gadaffi. They are accused of raping people in these cities, but the facts have never been proven.

After the Revolution, the Misratians retaliated against the Tawarghi people. 35,000 Tawarghi fled to camps scattered in the four corners of the country; their town was razed to the grown. Six years later, still without a home to go back to, the Tawarghi become scapegoats in an endless cycle of violence. The Al-Fellah camp, to the south of Tripoli, shelters around 2,500 Tawarghi.

Notebook in hand, Mahmoud settles into a small office lodged between two barracks at the camp’s entrance. The first person he asks to meet with is Ali, the man freed from the Tomina prison two weeks prior. Masked in pain and leaning heavily on a cane, Ali appears to be 65, though he is only 39. He lists the names of those who died in front of him and describes the scenes of torture, the dogs, electroshocks administered to genitalia, and more. During a small pause, Mahmoud interjects: “ You can tell me everything.” Ali sighs. “ They constantly told us, ‘Die, dog of Tawargha!’” Mahmoud takes notes. “ Some of us were locked up in a room, all naked, with groups of migrants.” Mahmoud asks, “ The whole night?” Ali nods, yes.

“ They were not released until they were all raped.”

Ali adds, in one breath, “ Luckily, I did not go through that. I only had the stick and the wheel.” Mahmoud lifts his head. “ Dozens of times,” Ali confirms, anticipating the question. “ And now I have physical problems: leaks.”

Mahmoud continues to take notes. The torture-by-stick method was brought up by another witness, Ahmed, who described in Tunis that if they wanted to have a chunk of bread, all the detainees had to impale themselves on a stick, fixed to the wall, until they bled. Then there was the car tire, another sadistic method of torture: the detainees would fold themselves through one side of a tire, suspended from the ceiling, so their rear ends could be tortured with rockets of different sizes.

“ I understand . . . are you getting treatment?” Ali shakes his head, no. It’s impossible. His testimony shares many elements with Ahmed’s testimony, heard in Tunis: the same torture methods as well as the raping of migrants. A new element of the story is the systematic targeting of Tawarghi men.

The next day, Mahmoud aims to meet with more Tawarghi victims. Thanks to his friend Mehdi, he is able to track down a woman whom he has known for a long time. She is sheltered further south, in another camp for displaced Tawarghis. Before, Fathia had never wanted to speak of her trauma. She opens the interview with a frail voice: “ At first, they took my daughter. She was 11 years old at the time. Then they assaulted my husband, who was a quadriplegic. One of the men tried to rape my daughter. He was one of our neighbors who had a daughter of the same age. I watched her grow up.” She sighed. “ They cornered me in a room in the house. They raped me twice, saying ‘You, Tawarghi, you will pay for Misrata!’ I told one of the men, ‘But I’m your neighbor, we’ve been living together for 20 years!’”

Mahmoud asks for the name of the rapist and writes it down, along with the name of the neighborhood. Fathia continues, “ They dragged me out in the street, in front of everyone, and said, ‘You raped our daughters. We will do the same to you’ . . . and they were not all Misratians. Then they raped me in front of my older brother. And the worst thing they did to me was rape me in front of my son . . . he hasn’t spoken to me since then.” Fathia can no longer hold back her tears. Mahmoud hands her a tissue and suggests that they stop. “ No!” Fathia responds, “ I want to talk!”

“ The second day, a man came in. Very strong, I didn’t know where he came from, if he was Misratian, Libyan, Syrian . . . he was there to rape.” Mahmoud watches her facial expressions change. He asks whether there were other detainees with her, other women? She shakes her head.

“ I heard screaming, but they were the voices of men.”

Fathia sighs. “ What I didn’t know, is that in the meantime, they had taken my third son who was 14 years old.” Mahmoud’s hands begin to tremble. Her child was held for three years in a prison close to Tomina; he was tortured by his jailers. And then one day, a miracle happens. “ My son called me. ‘Mom, I get out in five days’ . . . I ironed his clothes, prepared his bed, his favorite dish . . . I was so happy!”

Fathia takes her car and bravely crosses the area controlled by Misrati fighters to pick up her child. “ When I arrived, they threw a body bag at my feet . . . and they told me, ‘Here, here is your son, bitch!’” Fathia bursts into tears. “ I opened the bag, there was my little one, so thin, cheeks sunken, his body covered in scars.” She holds out a picture. Mahmoud drops his pen and breaks down in tears.

JunE 2017

Shortly after his return to Tunis, Mahmoud meets back up with Céline Bardet. He recounts the findings from his investigation in Libya: the 650 cases; the meetings with other activists, which confirm the use of rape in all the prisons of western Libya; and finally, the targeting of the Tawarghi people.

“ It has all reached a criminal level,” insists Mahmoud. “ Any ordinary citizen has the right to take a Tawarghi, to rape them, to torture them; it’s normal. Some even think of it as a national duty.” “ How many Tawarghi victims do you think there are today?” asks Céline. He estimates “ between 3,000 and 5,000.” Mahmoud adds, with exasperation, “ How can we alert the international community? Why hasn’t the ICC done anything?”

The time it takes for justice to take its course always seems too long for investigators on the ground. But as it turns out, the ICC had already relaunched the Libya file, discreetly at the beginning and then publically later on. In autumn of 2016, prosecutor Fatou Bensouda stood before the United Nations Security Council and requested more funds to strengthen and expand the investigations in Libya. She is aware that the Libyan case is in some ways a political bomb; to open an investigation on Libya means reconstructing the precise chronology of facts, identifying and listing crimes, and exposing the responsible parties.

The task is enormous. The ICC’s mandate concerns war crimes and crimes against humanity. Officially, Libya has not been at war since 2011 — except during specific battles such as Benghazi in 2014 and the recent battle in Sirte. To treat the Libyan cases, the ICC starts off by classifying the cases presented to them by the Libyan investigators: war crime . . . or crime against humanity? And which category to start with? The crimes against Misratians in 2011? Or those committed by the Misratian militias after 2011? Or the crimes against the Tawarghi? Or those committed by the Benghazians?

In the inextricable web that is the Libyan civil war, each party involved has committed heinous crimes.

The ICC’s responsibility is immense. In theory, the courts should wait until they have received cases from all of the various factions, so as to avoid bias. But it would take years for the investigative teams in The Hague to analyze the mass of evidence documenting six years of anarchy in Libya. To speed things up and get the job done, even the ICC needs help.

Céline Bardet, who started her career in the Hague, knows how to play this game. Mahmoud’s diligent work documenting the violations committed against the Tawarghi people has given Céline something to run with. If the file is put together and written correctly, they can accelerate the process for the courts. Céline drops the pile of documents onto the table and says, “ Listen, Mahmoud. In Bosnia, during the conflict from 1992 to 1995, there were war crimes and crimes against humanity. But in Srebrenica, an enclave of only 8,000 people, the crime was classified as a genocide, because there was the intention to annihilate the people of Srebrenica. We have to find the element of intention, because here we are, maybe – I say maybe – close to a genocide against the people of Tawargha.”

AUGUST 2017

While the activists in Tunis are busy building their case, the ICC hits a homerun. On August 15th, it issues an international arrest warrant against Commander Mahmoud Al-Werfalli, accusing him of war crimes. Werfalli controls the Al-Saiqa brigade, which is allied with General Khalifa Haftar, the man who, for years, has controlled the east of Libya.

The ICC submits its first evidence against Werfalli: videos posted online that show him carrying out summary executions. Consequently, General Haftar’s role is put into question. The investigators know that the collected videos are legally admissible pieces of evidence. And this blow by the ICC against the criminals in the east of Libya push the courts to consider the arrival of new victims, as potential witnesses, this time coming from clandestine jails in eastern Libya.

War crimes, crimes against humanity, and perhaps a genocide committed by its own population . . . in Libya, the rape of men has become a permanent weapon of war. With the help of Libyan activists, Céline Bardet and her NGO are preparing to release a report that will finally expose the horrors that have unfolded in Libya over the past six years. But the investigation is far from over. " We still don’t fully understand the scale of this crime. We are starting to have evidence, but it takes time." While the activists wait, there is more evidence to gather.