It's a ritual every morning in the office of the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD). The small waiting room, wedged between a detection scanner and a reception desk, begins to fill up. There is a noticeable lack of seats for the number of people present. The vast majority are men, but there are a few women, of all ages, waiting together with anxious faces. In their hands, a file: a few sheets supposed to contain the traces of the abuse that brought them here.

Each one receives his ticket and, when their turn comes, goes to one of three offices to submit their files. On the surface, the procedure appears like any other administrative formality, but what comes after is a long process to establish the truth and obtain reparations; the culmination of a long journey of injustice and violence in which many lives were lost. Emotion sometimes overwhelms the interview. The commissioners, notably Zouheir Makhlouf or Ibtihel Abdellatif, often intervene to offer support and comfort to those bringing cases forward.

These first interviews take place in private, but a few people were kind enough to share their stories.

AMINE MANSOUR*: Ten days of Torture and a family torn apart

"

I was arrested on February 6, 1994," recalls Amine Mansour, 52. “

Until then, I had a fruit and vegetable shop in France, in Clermont Ferrand. I used to go back and forth between France and Tunisia regularly without any problem. During one of my visits to Tunisia, I visited a childhood friend in Ben Guerdane. Shortly

afterwards, I was arrested. I think it was him who reported me to the police because I was praying and practicing [Islam]."

" I was first taken to Tataouine, then to Medenine, for three days. I was accused of belonging to an unauthorized organization: the Ennahdha movement. I had been a member of the UGTE (student union close to Ennahdha) when I was a student in Algeria in the late 1980s, but I was not a member of the party. Then I was taken to Tunis, to the Ministry of the Interior. We arrived at 4 am."

Amine Mansour recounts the beginning of the ordeal in flashbacks.

"I was placed in the General Director of Security’s office. He arrived at eight o'clock. A large basin of water with ice was brought in. I was then tied up by my feet and made to lower my head into the water. I was hit very hard in the stomach. I think the first session lasted about 10 hours."

Then the days of torture follow one after another. " I got it all, the roast chicken position, a stick passed between the knees and elbows, hanging between two, and beatings on the feet. I was hung by my hands tied behind my back," he says, mimicking the scene. ‘‘ It's a position that quickly became very painful, so much so that my torturers made me do an exercise from time to time to prevent my back from breaking. A doctor also came to see me every day and advised me to eat well," an intervention designed to stop the suspect from dying, not out of concern for their health but rather to prolong the interrogations.

"I think it lasted ten days. Then I was taken back to Medenine to sign off on my lawsuit. It was a way to erase the traces of the interrogations in Tunis. After that, I was sentenced to 3 years and 9 months. The police were disappointed, they had hoped I would have been able to endure more."

"

Shortly after this, I was taken back to the police in Medenine. This time I think they wanted to charge me with arms trafficking. I understood that this time I had to weaken myself. During the first set of interrogations, it was my physical resistance

that prolonged the torture, so I refused to eat. I fainted. I was dropping names to save time. Finally, after three days, they gave up."

Amine Mansour served his time. Released in 1997, he was in the " soft" prison of passport refusal and permanent judicial control. It was not until 2011 that he was able to travel to France again.

But the psychological and physical after-effects of the ordeal remain with him. There are scars and marks across his stomach from all the blows he received. It has also impacted his family. " In the end, I had to sell the business I had in France. It didn’t amount to much by that time. My son is handicapped and my wife is in France to take care of him. But my other son can't get a visa. I'm staying with him. Since 2013, I've been hired as an accountant at the Ministry of Agriculture. But my priority now is to try and reunite my family."

Kadri Lafi: To LIVE IN EXILE IS TO LIVE HALFWAY

Kadri Lafi, 49, speaks with an Italian intonation. That's because he spent 20 years living there, having been sentenced to a year and a half in prison in 1990 for " belonging to an unauthorized organization."

Originally from Sidi Ali ben Aoun, he was then a teacher.

"They insulted me, they beat me. I had a physical fear of violence. I was afraid of losing my dignity. At the time, a teacher was someone who was respected. In prison, we were supposed to be given common rights. During the month of Ramadan, food was brought to us at two o'clock. All this was a way of destroying us."

Once he was released, he was faced with a choice. "

I want to pay tribute to my father who said to me, 'Son, I am heartbroken at the thought of knowing that you are going to leave your land, your school, your family, but I refuse to see you tortured, broken and losing your dignity. Those who remained

have been destroyed.’ So I chose exile."

He was able to leave quickly for Italy with a passport that was valid for another four years. " Once the validity date of my passport expired, the Tunisian authorities refused to renew it and Italy wouldn't grant me political refugee status. For six years, without papers, I lived in permanent terror of being sent back to Tunisia. I was a citizen without rights. I couldn't marry my fiancée, start a family, or work.’’

Officially regularized in 2001, married in 2003, and later becoming a cultural mediator for foreign children after studying political science at university, Kadri was eventually able to lead an almost normal life.

"But living in exile is to live halfway. I couldn't communicate with my parents. Their mail would be opened. Even the people I would see in their homes were questioned."

The revolution allowed him to return to Tunisia. "

Reintegration was difficult. I resumed my job as a teacher and my career just as I had left it 20 years ago. I remember my first day of school when I came back.’’

"

I started by drawing two teachers on the blackboard, one with a stick, sitting above his pupils, the other in the middle with his pupils sitting around him in a circle. I asked the pupils which one they preferred, they chose the second one. I told them

this approach would require more work for all of us. By the end of the year, my students had learned to express themselves freely, to criticize each other without aggression or fear. Unfortunately, children are not at the center of the education system.

After 23 years of Benalism, for many, the goal is to satisfy authority rather than to act in the interest of others."

" We have a duty to save a generation from the consequences of the dictatorship that broke the spontaneous relationship between citizens and their capacity for collective initiative. A culture of fear has never created a civilization."

Why file a case at the IVD? " For me, the objective is to establish the truth. If those who inflicted all this on us are not brought to justice, we won't be able to get back on our feet. We must give the new generation hope that Tunisia can change."

Ahmed Slama: PETTY THEFT, BIG SYSTEM

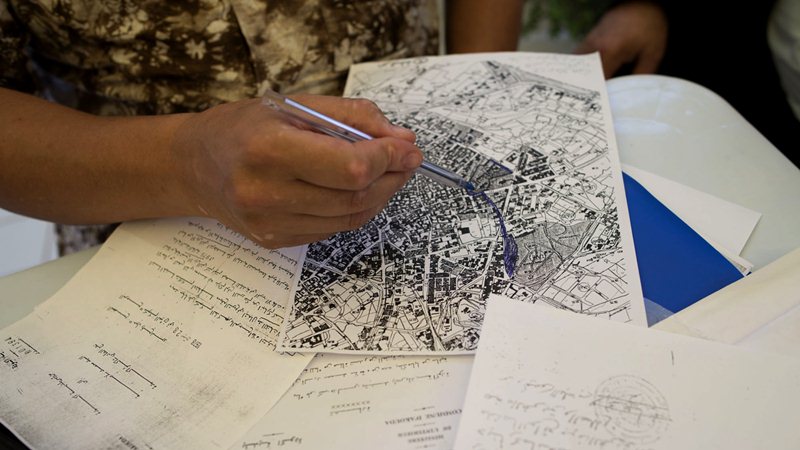

Behind the waiting room, the IVD has a large glass room where plastic tables and chairs are bathing in the warm light. Sitting at one of these tables, Ahmed Slama displays documents in front of him. In schoolboy fashion, he draws lines on a map of the land register and writes accompanying explanations on sheets of small squares. What is the point of this exercise?

"I'm drawing the boundaries of a 360 m2 plot of land that was confiscated by the municipality from my grandmother in 1978, in Akouda, a small town near Sousse."

"

My grandmother was offered a meagre compensation, 75 millimeters per square meter. The municipality used it to make a cemetery. In fact, there was already municipal land set aside for that cemetery. But the mayor took it for his house. That's why the

municipality took that land away from my family. My grandmother was illiterate and didn't understand her rights. She never even touched that money. Fifteen years later, my father filed an administrative appeal, but it didn't work out."

As the discussion goes on, Ahmed makes it clear that this was not an isolated case. "

Several dozen families were expropriated in this way in Akouda. Even the high school was built on stolen land. Besides, after the revolution, the family took it over and it became an oil press! This all happened during Bourguiba's time. It wasn't a

mafia, but the people of the party pretended to act in the name of the best interests of the state, when in fact, they were diverting part of it for their own benefit."

Ahmed Slama hopes that through transitional justice this piece of the land will be returned to its rightful owners, " part of it is salvageable."

Selim Gtari: THE HEIR IN SEARCH OF REHABILITATION

Selim Gtari, 33, changed his name on Facebook after the revolution to Selim Taieb Gtari, adding the name of his father, who passed in 2009. This merging of identities illustrates how trauma can be passed on from one generation to the next. Selim Gtari's story is one of a man who has been broken for his ideas.

"My father was one of the founders of the Perspectives movement, a far-left movement that has been the cradle for many other militant political movements in Tunisia. Originally from Djerba, then a student at Sadiki middle school, he passed his baccalaureate in 1962. At the time, that meant something. He left for Paris in 1963 to complete his studies."

His early years heralded a brilliant success. "

From the early 1960s, the regime began to lock itself up after the assassination of Salah Ben Youssef, the evacuation of Bizerte, and the execution of the perpetrators of the December 1962 coup attempt. Gathered by the Group for Socialist Studies and

Action in Tunisia (GEAST), young Tunisians, including my father, began to think about projects for society. He was part of the Maoist movement. He even went to China at the end of the 1960s. It was a time of turmoil."

But in 1968, the movement experienced its first wave of repression after protesting against the hijacking of the UGET student union elections in favor of the “destourians,” supporters of the regime. The movement’s leaders were placed on trial and Taieb Gtari was sentenced, in absentia, to 12 years in prison.

" In the years that followed, after the failure of Ahmed Ben Salah's socialist project in 1969, the regime redoubled its ferocity towards his followers, whom it prevented from contributing to the country’s development. My father’s position as an economics professor at Vincennes enabled him to help those fleeing repression. He was part of all the emancipation struggles of the time, and even helped the leading translator of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, the Palestinian George Habash. In 1974, he was convicted in a new wave of trials. He was only allowed to return to Tunisia in 1980."

"But the life that was waiting for him back home was not what he had hoped for. Bourguiba's oppression meant that he died a slow death. He was totally marginalized. Passport banned, deprived of work in the civil service."

"

Some activists accepted positions at the university, in the civil service, in exchange for their support for the regime, in the name of the fight against Islamism. He turned that down. He worked in a hotel in Djerba for a period, and even there, the

regime eventually found a way to force his employer to fire him. Our whole family was excluded. We were not invited to family parties. My uncle used to take my cousins to the beach, but never my brother and I. His brothers didn’t even leave him his

share of the family inheritance."

Selim's father died in April 2009, but the wound of that exclusion, of that broken life, is still there. " My father gave his life, his energy, his youth to Tunisian emancipation. The revolution is a posthumous victory for him. By submitting this file to the IVD, I am acting on behalf of my family, but also on behalf of all those futures that the regime prevented from hatching. Having my father's story heard by a state institution is already a form of rehabilitation. It is by establishing the truth that we will build a better Tunisia. Few left-wing people have come to the IVD because they don't believe in it. This is regrettable because they are going to prevent the whole truth about the old regime from emerging. Reconciliation cannot be achieved through denial. Tunisians need to know what happened."