Yves Eliahou Kamhi, 36 years old, is a Franco-Tunisian lawyer who still lives in Boujaafar, his birthplace in the Tunisian governorate of Sousse. His childhood was rich with experiences. Even as he grew up spending his time in the synagogue next to his house, his mother still enrolled him in an Islamic " kotteb," where he would learn to read and write from the Koran, two years before starting school.

When he was at school, Yves didn’t feel he was any different from his classmates. As he has grown up, he finds himself forced to " choose" his identity and live a fractured existence in relation to the rest of society.

"I am a Jew by conviction and by acquisition,” he says , “I was born a Jew and I chose to remain one. I didn't want to leave the country or stay here by changing my religion - I have never thought about it. I am Tunisian first and my Jewish identity comes second."

The Kether Torah synagogue, where Yves grew up, was built in 1913 by the Rabbi of Sousse, Youssef Guez, who later became the country’s first Chief Rabbi of Tunisian origin. The synagogue was a mausoleum once visited by thousands of Jews, who have honored religious rituals and celebrated holidays there.

As his family home was next to the synagogue, Yves was immersed in the culture and heritage of Judaism from an early age, regularly taking part in ceremonies like the Shabbat prayer. To perform this prayer, 10 pubescent men over the age of 13 are called on. After the Jewish community in Sousse began to Diminish, Yves, aged 13, completed the quorum so that this weekly prayer could continue.

" It was a very strong existential and spiritual experience for me, I felt that I belonged to the Jewish community, while at the same time remaining open to Muslim culture.’’

OF JEWISH FAITH AND MUSLIM CULTURE

Being of Jewish faith did not prevent Yves from being interested in Islam. At a very young age, he became interested in reading the Koran; the Prophet's Hadiths, the account of the life of the Prophet's companions; and books specializing in Islamic schools of thought. He even confides that he excelled in the subject of religious education during high school:

"I was a good reader. This religion intrigued me a lot as it is the backbone of Tunisian society and the main component of its civil and cultural sectors. I read and reflected a lot and I found that there are many more points in common that bring Muslims and Jews together than points of difference. Sometimes when I open the Koran or go into a mosque, I have the same feeling as when I open the Torah or go into a synagogue.’’

Yves is a complex character, lighthearted and emotionally deep at the same time. A man of Jewish faith and Muslim culture. He is very rational, with each step being carefully considered. His personality does not leave the slightest room for spontaneity or exaggeration, especially when it comes to religious or ethnic issues.

"It's retrograde! Such differences are an enriching factor in society. Why consider it a danger that threatens society and its solidity?’’

For Yves, Tunisian society is static, superficial, and refuses to open up to others. Consequently, it refuses to open up to itself and to its own differences and paradoxes.

In Tunisia, he has very often been a victim of anti-Semitism because of his religion. He no longer counts the times " Too bad, we thought you were Muslim" is uttered as soon as someone becomes aware of his religion. Others go so far as to exclaim, " We thought you were Tunisian." His Tunisian identity comes into question as soon as he confesses his faith.

The police themselves are also discriminatory; some officers do not understand that Yves is a full-fledged Tunisian citizen, enjoying the same rights and duties as his fellow citizens, the majority of whom are of the Muslim faith.

He recalls an event that happened to him while he was travelling to the Ghriba pilgrimage, a sacred event in Djerba:

"I was on my way to the synagogue for the Ghriba pilgrimage when a policeman tried to stop me from passing, arguing that the event was only for Jews. Judging me by my tracksuit top, with the logo of the [Sousse-based] Etoile du Sahel [sports club], he thought that I had little interest in the event. When I explained to him that I am Tunisian of Jewish faith, from Sousse and a supporter of the Etoile du Sahel, he exclaimed with contempt: a Jew and a Sahelian supporter at the same time? May God preserve us!''

The KEEPER OF ARIFACTS

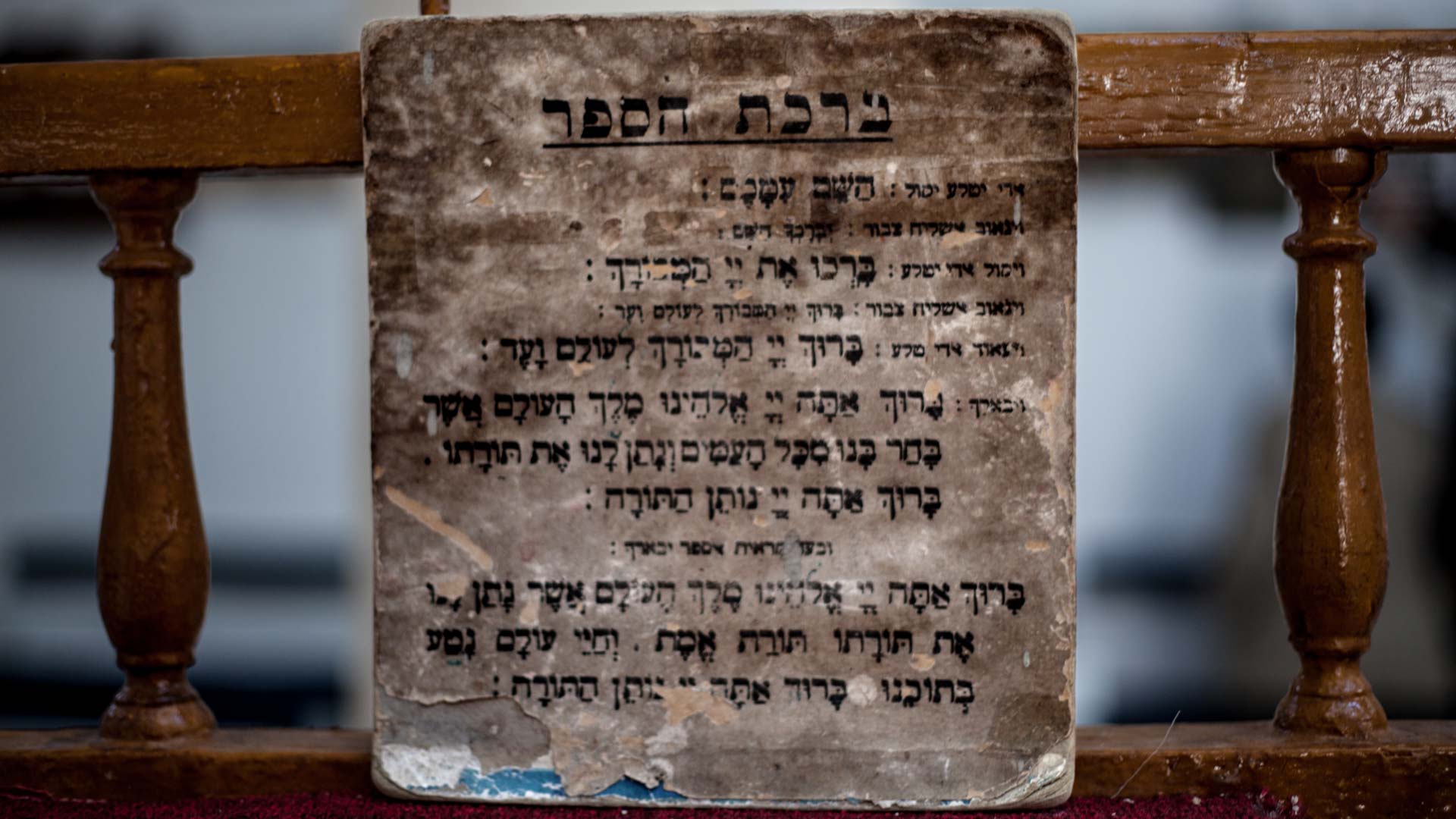

It's not difficult to get into the synagogue. The walls, despite the recent maintenance efforts, seem dilapidated and the locks do not appear solid. But behind these walls is a priceless relic: an artifact with immense religious importance that represents an almost forgotten civilization. And by chance, Yves is the guardian of this heritage, entrusted with safeguarding its message and handing it down to future generations.

Yves opens the door of a patio decorated with paintings and Hebrew expressions and stands devoutly in front of a door, quietly reciting prayers. Then he wipes his forehead with his right hand before pointing to a decorated cylindrical room. In a gesture marked by prudence and piety, he opens it and shows us a Torah manuscript that has been handed down from generation to generation:

"This manuscript is sacred and very rare. The largest synagogues in the world, like the one in Jerusalem for example, contain only two or three manuscripts. Our small synagogue contains thirty! They are all ancient and handwritten. It is a human treasure in the truest sense of the word. It's a priceless treasure.’’

In the past, Jewish ascetics spent long periods in the synagogue, sometimes two or three years. During this period, they wrote the Torah by hand, on special paper, and with indelible ink. After the writing was finished, the manuscript was kept in a wooden box, which was displayed during a ceremonial walk through the alleys of the medina to celebrate its completion.

During the last fifty years, many synagogues in the Sahel - the country’s central eastern region - have been abandoned, such as those in Moknine and Monastir. This is why all of the manuscripts were transmitted to Boujaafar, which, despite also showing signs of neglect,, still houses these artifacts. Yves, the man chosen by destiny to be their guardian, has never ceased to appeal, in vain, to the authorities to help maintain the synagogue, especially as there has been a lack of action taken by the " provisional body for the safeguard of Judaism," he notes.

"Agents" AND "traITORS"

‘‘ What could be more unbearable than living in a country where one is perceived as “a devil” and “a presumed enemy” by their compatriots on the grounds of religious differences?’’ Yves says that this feeling is painfully heightened when these anti-Semitic ideas are disseminated from those at the top of society to state institutions, which treat him as if he is a “ traitor” intent on “ damaging the country.”

Once he reached the legal age for military service, Yves faced this reality. He was refused entry and rejected because of his religion. This decision was made contrary to the law, which, in theory, puts all citizens on an equal footing in terms of their rights and duties.

Yves says that he became used to being arrested during round-ups in his late teenager years, but he would be released, as soon as his faith was uncovered:

"At first, I didn't know what was going on. It was only later, when I wanted to clarify my legal situation by becoming a lawyer, that I understood Jews could not do military service. It is from that incident that this adventure and my feeling of oppression are rooted."

Yves filed a request at the Sousse police station to clarify his situation, regarding the fulfillment of his military duties. From his understanding, he needed to either obtain a postponement or perform his service. But his request was systematically refused. He then went directly to the relevant administration in El Omrane, in the suburbs of Tunis. There again, he was refused. But due to his perseverance, the authorities were unable to continue ignoring him, especially since there is no legal reason to prohibit a Jew from performing military service. It appeared that this ban must have been applied unofficially, likely since the foundation of the Tunisian army following independence.

Yves did some research and found two possible explanations: either it is a culinary reason, as the army is not able to prepare kosher dishes, thus making Jews exempt from military service, or the army fears tensions and potential conflicts between Muslim and Jewish soldiers and consequently feels the need to create cleavages within the army.

Little convinced by either of these answers, Yves arrived at a third conclusion: the refusal of Jews into the army is linked to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In the mind of the Tunisian state, a Jew can only be a Zionist, making his commitment to the Tunisian army entirely secondary to that of Israel. In their eyes, this could lead to a breach of trust and potentially endanger military secrets.

"In the eyes of the Tunisian army, we are traitors on probation. That is why we are forbidden to carry out our military duty. We are second-class citizens. This is shameful! Neither the Constitution nor international conventions can put an end to the discriminatory treatment that we are subjected to. Yet our national anthem says: May no one who betrays it live in Tunisia. Let no one live in Tunisia not serve in its ranks! We are not among its soldiers. Or rather we are forbidden to count its soldiers. Is that fair?’’

While the Tunisian army discriminates against Tunisian Jews in a roundabout and unofficial way, constitutional law openly excludes non-Muslims from running for the presidency: " We are not interested in this position. But the fact that our right to run for office has been taken away from us has affected us greatly and confirms the idea that we are second-class citizens."

THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF LOVE IN THE NAME OF RELIGION AND CULTURE

If a young Jewish man is single, it’s not out of choice, it is because he hasn't found another Jewish woman to marry. Judaism is a " difficult and complicated religion, which allows marriage only to people of the same religion. This is a condition that can pose a lot of problems for Jews in Tunisia, as elsewhere in the world.’’

Yves stopped having romantic adventures a long time ago. He has placed tight restrictions on himself and has closed his heart off to non-Jewish women. He knows that, in the end, loving a woman of a different faith only complicates his situation and creates conflict between families of different religions. This is a situation that young people around him have also experienced.

After a long pause, Yves ends up confessing that he has had several love affairs with women of other faiths. But with each caress, each kiss, each "I love you," he knew he was making a mistake:

"Feelings and emotions quickly give way to opinion and debate. A religious and cultural discussion then takes over, not to mention a possible confrontation between the two families over different beliefs."

In a corner of the room, Rachel Belhass Malih, Yves' mother, is daydreaming. This elderly woman suffers from Alzheimer's disease but has not forgotten that her son is yet to find himself a sweetheart.

With her Sahelian accent, this woman from Moknine lists the assets she requires from her son's future wife: " She will have to be very beautiful, with a clear, soft, and kind complexion." Once the list is finished, she returns to her thoughts and starts daydreaming again, while whispering the words of an old Jewish Tunisian song. It is a song that speaks of marriage, the obstacles that can meet couples, and which concludes that, if single, it is preferable for a man to take a Muslim woman as a wife.

For the moment, Yves devotes his time to his mother, whom he adores. She is for him a mother, a sister, a friend... his only love. He spends his days in her company and prepares food for her when he is not working in his office, just a few steps away from his home.

Since her illness, he feels the need to have someone extra at his side: a woman with whom he can share his life. But where can he find a woman who fits the criteria? How do you find a Jewish woman willing to marry in your area?

"In the 1960s, there were about three thousand Jews in the Sahel. Today, there are about 50, of which about 30 are elderly."

Migration to Europe or Israel explains the decline of the Jewish population in Tunisia. For Yves, the departures are because people are looking for a quiet life, without discrimination. These departures have created a vacuum, leaving the Tunisian Jewish population under-represented and lacking political influence.