Since he left, his brother Moncef has taken responsibility for the family farm. He is one of half a million* small-scale farmers who are now faced with a production structure that does not enable them to make a decent living through their occupation. According to sociologist Laroussi Amri**, small-scale agriculture has been threatened by a large number of restrictions, and run " the risk of extinction, plain and simple", for several years. This is despite the fact that agriculture alone supplies the majority of the local Tunisian market, amounting to around 60% to 70% according to estimates by several specialists contacted by Inkyfada.

" I SPEND MORE THAN I EARN, IT'S ABSURD"

Four cows, a few chickens and vegetable plots - two hectares in total - surround the modest farmhouse where Moncef and his family live. From 5 o'clock in the morning, Moncef is busy milking the cows in the cinder block barn, before the milk collector comes by. He then goes to the fields where he continues to work tirelessly until sunset. Moncef produces a variety of products, all depending on the season. In November for example, the fields are full of onions, peppers, spinach or parsley.

Out of the eleven children in the Ghanay family, only two are currently tending to the lands. Moncef works for days on end, and for very meagre rewards at the end of the harvest. For potatoes sold at 610 millimes per kilo, he spends an average of 580 millimes. " I make a profit of 30 millimes, it's absurd", he laments. What costs him a lot are seeds and supplies (fertilisers, manure, pesticides, etc.), which weigh heavily on his budget.

These products, imported from abroad, make up the essentials of the Tunisian market. Introduced in the 1960s by the World Food Aid Programme (WFP), hybrid seeds now dominate the Tunisian market. These seeds, produced in laboratories of major agrochemical factories, have gradually replaced indigenous varieties. According to Article 3 of Law No. 99-42 of 10 May 1999*, only seeds registered in the official catalogue can be marketed in Tunisia since the late 1990s. " This catalogue contains mostly hybrid and non-self-reproducing varieties, which forces farmers to repurchase seeds each year, and creates a system of dependency", says Nada Trigui from the Tunisian Permaculture Association (ATP).

These are the seeds that Moncef has to buy, at a high price, and from major suppliers. They are poorly adapted to the particularities of the Tunisian climate and require intensive use of pesticides, which ironically enough are referred to as " medicines". These products " deplete the soil and encourage the development of increasingly resistant pests", according to May Granier, a member of the Tunisian Association of Environmental Agriculture.

Hosni talks of a spinach field, yellowed by mildew, a disease that devastates crops. " We have to spray them with pesticides, but the bottle costs 140 dinars, which is more than the spinach itself will bring in. The crop is doomed, we're left with no options." For example, the seeds and supplies alone account for 80% of the costs of producing potatoes, according to information collected by Nada Trigui.

The list of costs does not end there. In addition to these expenses are the labour and transportation costs. " Last year, I sold all of my dates for 7,000 dinars", says Aymen, a farmer in the Tozeur region. " To produce them, I had to spend 6,600 dinars, of which 500 was for transportation to Tunis. For a whole year's production, I only earned 400 dinars, which is barely more than an average monthly wage."To be able to survive, Aymen nibbled at his modest assets, selling a sheep here, an agricultural tool there... until the same cycle starts again the following year. " If I had to start adding up all my expenses, I'd quit this job", jokes Moncef. But the tone is bitter.

" We work to survive", sighs Hosni.

" The first priority is to repay the debts", confirms Layla Riahi, a member of the Working Group for Food Sovereignty. " The farmer doesn't even realise that he himself hasn't been paid, and that he is working at a loss (...) Small-scale farmers are the big losers in the current agricultural system."

The pricing war

On the 6th of May 2020, small-scale farmers in Jendouba dumped a large quantity of potatoes on the public highway as a demonstration of desperation*. In addition to the high production costs, this year they were also unable to sell off their stocks, even at marginal prices. The Covid-19 crisis has only worsened the situation for the farmers who are already at the mercy of the middlemen, who often take the majority of the added value from the sales.

Moncef knows this all too well. Once a week he goes to the wholesale market in Jendouba to sell his goods. This means one day less in the fields, with no guarantee of being able to sell his vegetables. Once production is finished, it's a race against time. Without the possibility of storing his produce (like most small-scale farmers), he has to sell off his produce as quickly as possible, with the risk of losing everything. Tomatoes, for example, cannot exceed more than two days of being harvested. This is where the middlemen come in, with their means of storage and transportation to get their produce to the big cities.

Price negotiations are rough, and often to the disadvantage of the farmer. Even at the wholesale market, where sales are made to the middlemen, the farmers are not guaranteed to sell their produce at a price that allows them to support themselves. " Normally, each product has an official reference price, negotiated by the unions. But these prices are often non-binding, no one is there to verify their application, so certain people inevitably abuse this", says Nada Trigui.

She recounts that one farmer as a result of this ended up selling his dates at 1.8 dinars per kilo, while the reference price was set at 2.7 dinars. This meant a loss of a third of the total amount for this farmer.

At the very end of the chain, in the big city displays, the prices are much higher: " Just imagine, a kilo of pomegranates sold for 1.2 dinars in Gabès can end up costing more than 3 dinars in Tunis. It is clear that the middlemen are stuffing their pockets", says Rim Mathlouthi, president of the Tunisian Permaculture Association. During price negotiations, farmers (coming in last within the supply chain), rarely get the last word. " Intermediaries disconnect the producer from the consumer. There is simply no organised agricultural sector that can guarantee a fair distribution of profit."

" So it's always the small-scale farmers who get short-changed", Karim Daoud admits.

Some hard-line farmers refuse to sell at ridiculously low prices and end up letting their produce rot: " This year, the melons and watermelons stayed firmly in the fields. Farmers already know how it will play out and prefer to throw them out in protest rather than sell at these prices", reports Rim Mathlouthi.

MONO-CROPPING, AN ENTRAPPING PRODUCTION MODEL

The traditional model of crop diversification still practiced by Moncef and his family allows them to live self-sufficiently, despite the many difficulties. But this way of life is now threatened by the spread of a standardised agricultural model based on mono-cropping. Backed by public policies for many years, this way of farming is essentially aimed at export. To date, around 60% of small-scale farmers are said to practise mono-cropping, according to the estimates of May Granier.

In Cap Bon, it is the Maltese orange (a major staple in the French market), which has become the flagship product, with 95% of its production intended for export*. Rim Mathlouthi reports that farmers in the region have gradually been switching to mono-cropping citrus fruit in the hopes of one day exporting the fruits of their harvest.

" There’s a lot of fantasising involved", she says. " When a farmer thinks of export, he thinks of currency: of Euros. He then enters a cycle that seems lucrative to him. but which in reality, is to his disadvantage. This is because the ones who really make money from exporting are the middlemen, in a system that actually corresponds to market demands", she continues.

In Tunisia, it was the colonial powers which introduced specialised farming through various policies aimed at the modernisation of agriculture. " After Tunisia's independence, the state took back the land, and the system with it. It even strengthened it, continuing to encourage mono-cropping, especially in order to boost exports", says Layla Riahi.

However, a farmer that only grows citrus fruits is today no longer able to ensure the alimentary and financial independence that diversified agriculture provides. " No mono-cropper will ever make enough to support a household for a whole year. To ensure a steady income, one must diversify and rely on livestock farming, vegetable plots, arboriculture... It is also the only way to survive in the arid climate we live in ", May Granier maintains.

" Small-scale farmers have been made dependent on conventional agriculture and supply-based mono-cropping", Nada Trigui.

In addition to making farmers and their expertise more vulnerable, this production-oriented agriculture is based on intensive use of water resources and supplies, meaning the end of natural balance. In Cap Bon, the escalation of Maltese orange production has been based on the construction of an irrigation system transporting water to the region from the north-west. " This reservoir was originally intended to partly irrigate small-scale vegetable growers, but it is the large orchards that benefit from it in the end. Additionally, all the land surrounding the orchards has dried up and been contaminated", says Layla Riahi. " What's more, irrigating trees is absolute nonsense."

THE ARRIVAL OF INVESTORS, AND THE DEPARTURE OF FARMERS

" I have never managed to get a single credit loan", Hosni laments. With no help and drowning in debt, he had no choice but to give up farming. If the prospect of farmers remaining in the countryside is under threat, it is also because they are being excluded from support and credit systems.

For a farmer, obtaining government subsidies or credit loans from banks is a difficult task. According to a recent report by FTDES, only 3.7% of applications for credit loans in the countryside* were submitted by small-scale farmers**.

The first requirement is to be in possession of a " blue certificate", a property deed which a large proportion of farmers do not have for reasons of inheritance and administrative disorder. Without this certificate, they are not officially recognised as farmers and have no access to social security.

Even for those in possession of a blue certificate, it is mandatory to be able to present a written development plan that complies with the expectations and specifications of the creditors, in a sector where 46% of the operators are illiterate*. " And in any case, he had to have money to invest in this development plan, which is impossible for most of them. They barely have enough to meet their daily needs", says Layla Riahi. Loans and grants are therefore only available to those who are able to invest money, i.e. investors. " In Tunisia, it's the APIA (Agricultural Investment Promotion Agency) that defines who is entitled to subsidies. They never visit the small-scale farmers in Testour, but rather to those who already have access to credit", she adds.

" The investors are the ones who receive all the subsidies. It's a complete network of rentiers, connected to banks and authorities, and who have only one goal: to get more and more money", Layla Riahi.

In addition to monopolising the vast majority of finance options, these large-scale farmers " covertly expropriate the farmers' land through an active land acquisition policy, encouraged by the state", she denounces, adding that this is particularly noticeable in regions such as Regueb (part of the Sidi Bouzid governorate), where small-scale agriculture is in a particularly bad state. Crippled by debt, bankrupt small-scale farmers often have no choice but to sell. " You have to put yourself in the shoes of a small-scale farmer, struggling to survive on two hectares of land. If you offer him [a reasonable amount] to buy his land, he will give in right away", says Aymen Amayed, an agricultural engineer and food sovereignty specialist.

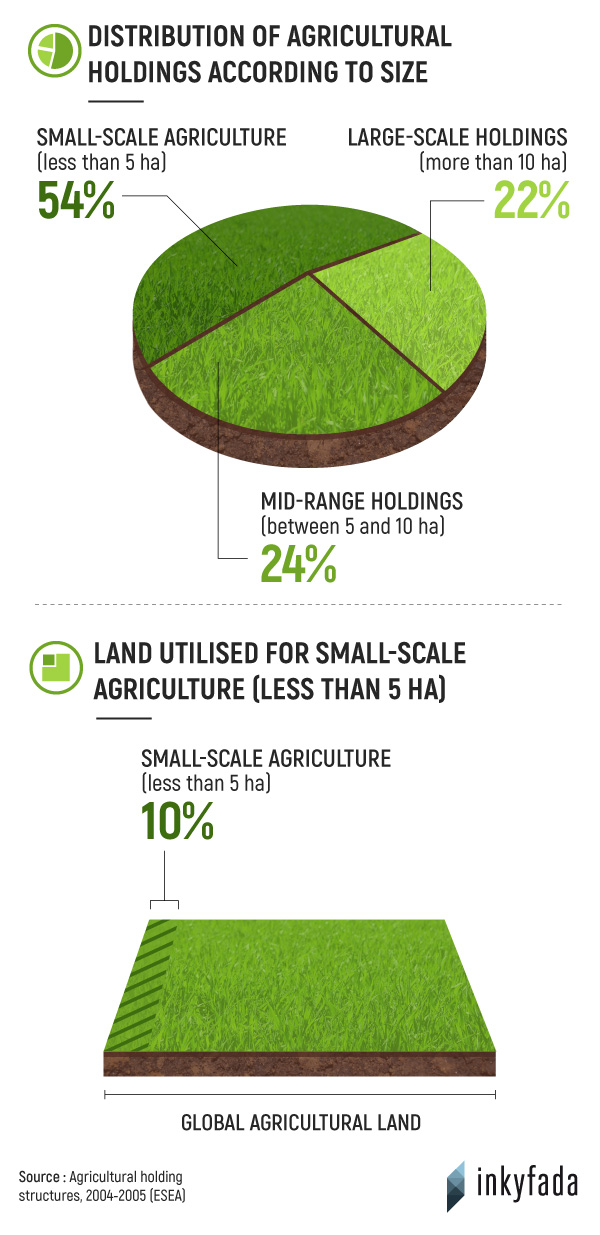

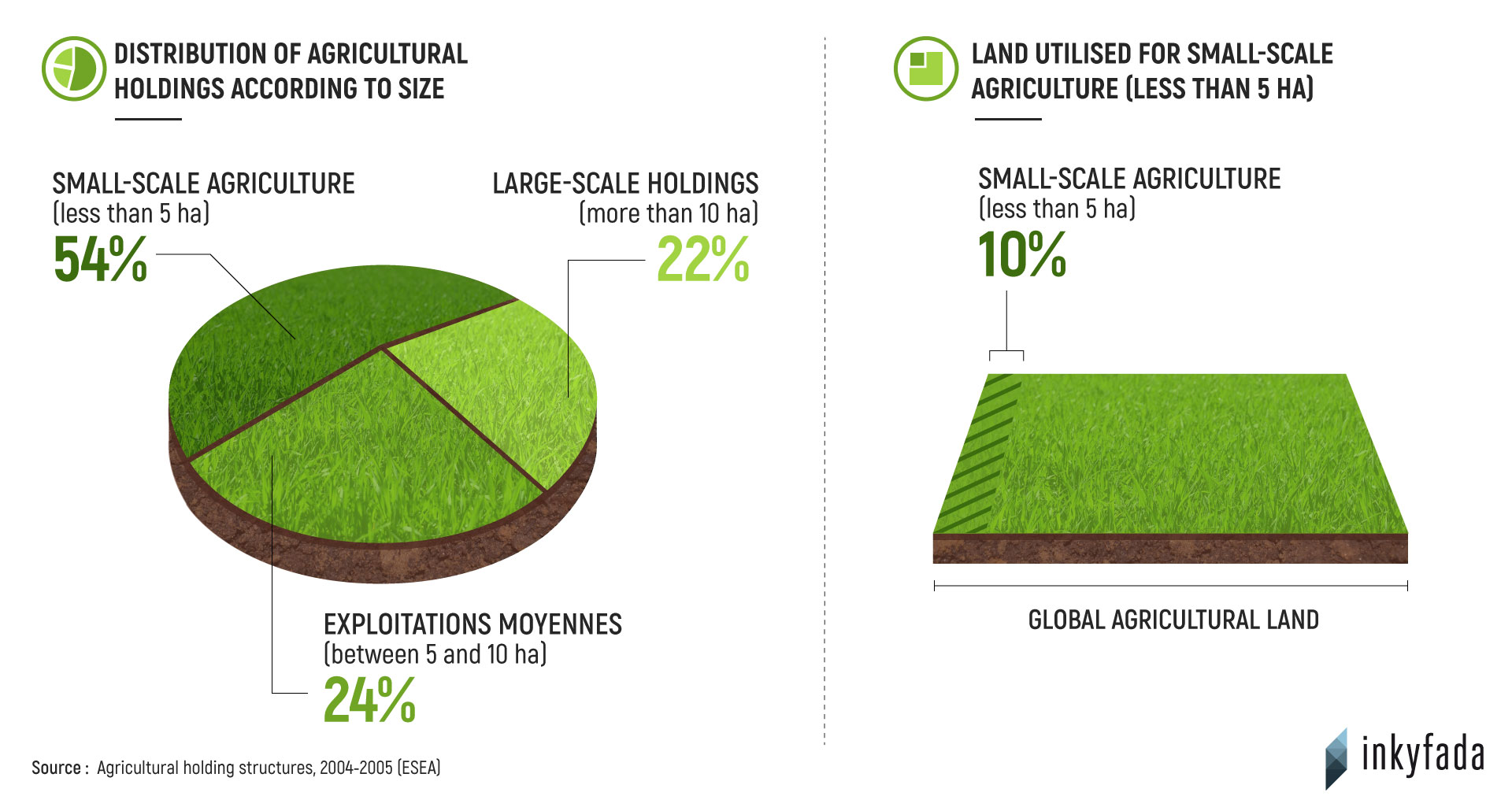

The majority of agricultural lands are owned by a small minority of investors and large-scale landowners, while the majority of actual farms are owned by small-scale farmers.

SMALL-SCALE FARMERS, systematically NEGLECTED BY INSTITUTIONS

Moncef recalls: " At the time, my father used to call in an extension worker whenever he needed advice on the crops. Today, the only one I call is my supplier. I am alone." The agricultural extension worker, an agent of the Ministry of Agriculture, is responsible for supervising and advising farmers on their crops and suitable treatments. This job is now in a significant decline. " Most of the retiring extension workers are not being replaced, and those who remain don't have cars and are unable to visit the farms", says Layla Riahi.

For Karim Daoud, president of Synagri, the country's second largest agricultural union, this is symptomatic of " the state's gradual disengagement with the agricultural sector over the last twenty years. The link between the state and farmers is virtually non-existent. Farmers no longer feel supported, and are giving up".

" There is no way for us to compete with these giants", Hosni protests. " We are not supported or represented by anyone, that's why I've never joined a trade union." Confronted with this testimony, Karim Daoud " [understands] why the farmers are disappointed. There's no visibility, and it is incredibly difficult for us to autonomously make ourselves heard by the government".

The recent FTDES report also points out that the farmers suffer from a serious lack of legal recognition and representation. Indeed, there is no clear status for small-scale farmers in Tunisia. " No status and no protection, which illustrates the great lack of interest in this field of production", explains Aymen Amayed.

" My eldest son Ali wants to take over the farm after I leave. I keep trying to dissuade him, I don't wish this life for him", sighs Moncef. In view of these poor conditions, small-scale farming is in danger of completely disappearing and, according to the latest available figures (2005), some 500,000 jobs are at risk in the sector where the unemployment rate was already at 15.3% in 2015*.

But beyond mere employment, it is the extinction of a local expertise and agricultural system that is tailored to the specific conditions of Tunisia's climate and its farmers which is at stake. " As it encourages diversification of resources and the maintenance of a resilient ecology, small-scale agriculture is the model best suited to respond to the climate challenges ahead. It is the future of agriculture", concludes May Granier.