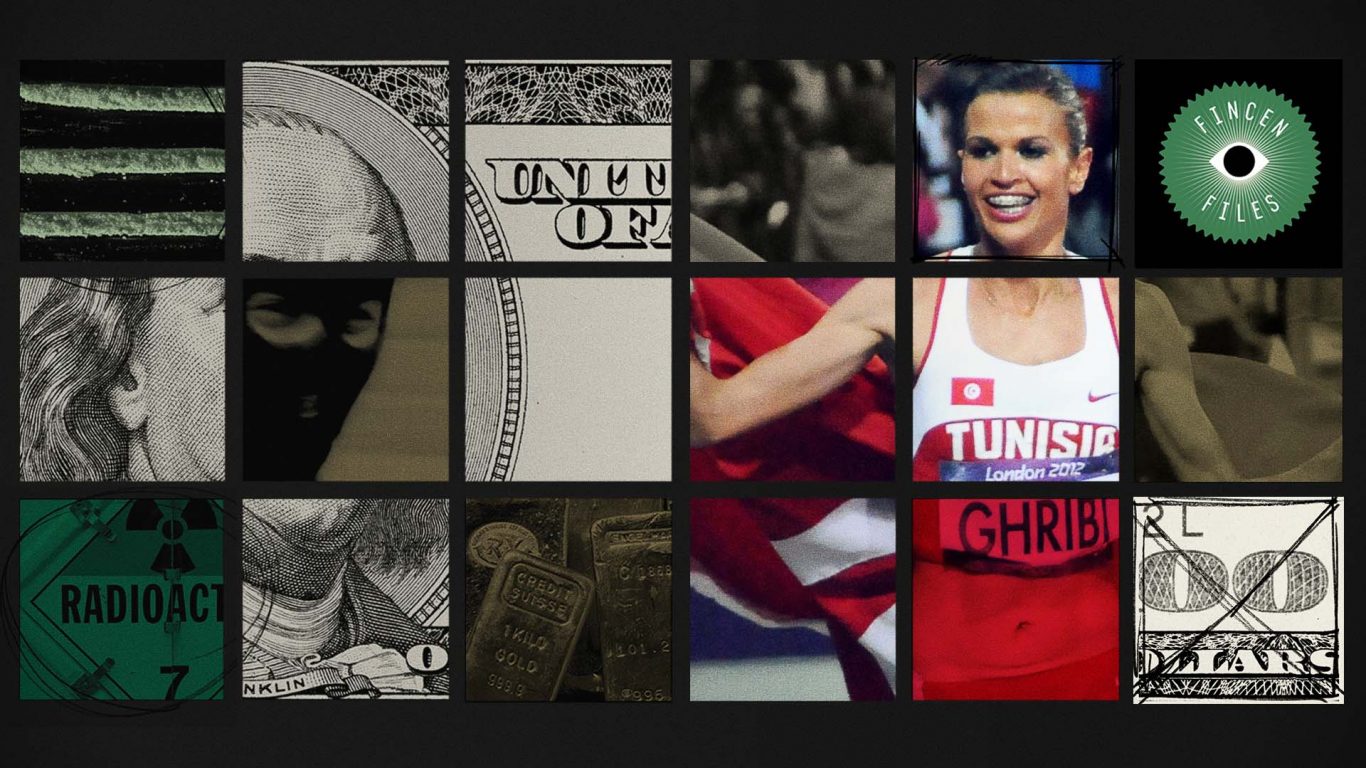

A Senegalese in Paris, and a Tunisian athlete

When he was president of the IAAF, Lamine Diack joined a vast network of people involved in what prosecutors describe as one of the most daring doping schemes in the history of sports.

During the 2012 Olympic Games, Lamine Diack and his son received millions of dollars in bribes, directly or indirectly, to cover up the results of anti-doping tests. French prosecutors claim that these tests were proof that Russian athletes had taken performance-enhancing substances.

After the scandal broke, the World Anti-Doping Agency found that Diack had "endorsed and appeared to have had personal knowledge of the fraud and extortion of athletes". The Agency also stripped several Russian athletes of their Olympic medals.

This dirty money is merely a fraction of the dollars, francs, rubles, renminbi, and euros that would have ended up in the pockets of coaches, doctors, administrators, and government ministers as part of one of the biggest scandals within athletics.

Along the way, many athletes were robbed of their dreams.

Russia's Yuliya Zaripova received the gold medal in the 3000m steeplechase of the 2012 London Olympic Games in front of an enthusiastic crowd and millions of viewers.

Tunisian runner Habiba Ghribi finished second on the podium.

Yuliya Zaripova was stripped of her victory in 2016 after a new anti-doping test confirmed that the results of the first positive test had been concealed. Habiba Ghribi was later awarded the gold medal at a small ceremony that took place on a Sunday evening near Tunis, on the sidelines of a young adult athletics tournament.

This doping operation robbed the Tunisian athlete of her victory, as well as tens of thousands of dollars in earnings and sponsorship contracts. Meanwhile, millions of dollars have passed through international banks, benefitting the members of this political and sporting network. The money has travelled from the IAAF to the Russian government, from Dakar to Moscow through Monaco, without arousing suspicion from the authorities that are monitoring these financial transactions.

On the same subject

This information comes from a secret financial database obtained by BuzzFeed News and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).

The disclosed documents, called " FinCEN Files", include more than 2,100 suspicious activity reports written by banks and other financial actors, and have been submitted to the U.S. Treasury Department's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN).

According to BuzzFeed News, some of these files were put together as part of the U.S. Congressional Committee's investigations into Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, while others were collected as a result of requests made to FinCEN by law enforcement agencies.

The dense reports, made up of technical newsletters, are the most detailed U.S Treasury records ever released. They reveal transactions processed by major banks, including HSBC, Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan, Chase and Barclays.

They outline dirty money transfers that continue to flow freely around the world: from the loot of a kleptocrat or shell company on the Atlantic coast, to a bank on Wall Street, to a sunny tax haven in the Caribbean or a financier in Damascus.

Four hundred journalists from nearly 90 countries delved into these leaked files; but the traces often led to a single name or address. They spent 16 months searching various sources for additional documents, reading extensive court and archival records, interviewing victims and combatants of crimes, and examining data on millions of transactions between 1999 and 2017.

Armed with these secret files, reporters traced the dollar trail between a Rhode Island drug trafficker and a chemist's lab in Wuhan, China. They investigated the scandals that crippled the economies of Africa and Eastern Europe, to the Venezuelan tycoons who siphoned off money from public housing and hospitals. They followed grave robbers who stole ancient Buddhist artifacts and sold them to New York galleries, and examined the largest gold refinery in the Middle East that's at the heart of a vast uncovered money laundering operation.

Among the dozens of political figures that feature in these documents is Paul Manafort, who was Donald Trump's former campaign manager, and convicted of fraud and tax evasion. JPMorgan Bank reported a transaction between Manafort and one of his associates' shell companies as recently as September 2017. This took place after reports emerged regarding suspicions of money laundering and links with Ukrainian officials with ties to Russia.

Dozens of articles in the FinCEN Files investigation trace similar money transfers. These include foreign capital to companies that exist only on paper, processed by international banks that have long served the oligarchs and despots, and that have been under no real pressure to stop.

This system has had lasting and disastrous consequences for the lives of many people.

The files contained in the FinCEN database were obtained by BuzzFeed News and shared with ICIJ and its members. These files are known as SARs (Suspicious Activity Reports) and provide a global overview of crime, corruption and inequality. The main players are unscrupulous politicians, oligarchs, crooks, as well as bankers who use their services to benefit members of this network.

The SARs demonstrate how the inability of banks and other financial institutions to thwart the flow of illicit money leads to large-scale crime and collateral damage.

The SARs are not necessarily evidence of wrongdoing. They reflect the views of the banks' watchdogs, called " compliance officers ". These officers report transactions that bear the hallmark of financial crime; those involving high-risk customers and those who have previously been in trouble with the law.

In a world plagued by headline-grabbing crises like the coronavirus pandemic, the unregulated flow of dirty money may not be considered an immediate threat - but the consequences are serious, as drug traffickers and crooks are placing profits out of the reach of the authorities. This enables despots and corrupt industries to inflate their incomes and consolidate their power, while governments, deprived of income, struggle to afford medicine to treat the sick.

"People may not be aware of problems like money laundering and offshore companies, but they feel the effects of it every day, because they are the ones paying the consequences of large-scale crime - from opioids to arms trafficking, to the misappropriation of unemployment benefits linked to COVID-19", said Jodi Vittori, an expert on corruption at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

However, organisations and law enforcement are aware that this covert flow of vast sums of money is the source of success for this criminal network.

An overdose in Garland

Emily Spell hears screams from outside of her parents' red brick house. She finds her brother, Joseph Williams, 31, lying on a mattress in the basement. His eyes, half open, are yellow and his lips are blue. His wife, Kristina, hits him in the chest.

"Joe, wake up! Joe, wake up!", she shouts.

Nursing student Emily Spell begins CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation). Every time she presses down on his chest, white foam comes out of Joe's mouth, dripping down onto his favourite Batman pysjamas. Joe's mother, who ran home from work at a regional grocery store in Garland, North Carolina, is lying next to her son.

"It's okay, baby, you can fall asleep", she says. "Do you want a cigarette? Are you cold?"

"I thought my mom was out of her mind", Emily recalls. “Of course he was cold. He was dead."

Joe's family does not know what killed him. They have no idea that he was one of the first of tens of thousands of Americans to fall victim to Fentanyl, the world's deadliest narcotic. A few days before his death, Williams had received a package sent from Canada with five painkillers and Fentanyl powder.

It took a smuggling ring that extends to China, and the flow of dirty money through reputable financial institutions, to deliver lab-designed opioids to rural North Carolina and across the country.

The money trail: Images of cash cover the window of an income tax office in the rural town of Garland, North Carolina, USA. Photo credit: ICIJ/Travis Dove.

"Emily, what the hell is Fentanyl?"

Standing in her daughter's kitchen, Joe Williams' mother is clutching the toxicology report that arrived in the mail that day, in 2014.

Emily Spell had heard about this opioid in nursing school. "It's like a pain medication they give to cancer patients", she says.

" Greatness grows in Garland" is the slogan of this small North Carolina town of just over 600 people, surrounded by blueberry fields and hog farms. But evidence of this greatness has been harder to find for people of Joe's generation. There has been no construction of new homes for years, and local officials recently disbanded the police force due to budget constraints. Over the years, many downtown businesses have closed. Weeds are growing in the cracks in the asphalt of the empty parking lot in front of the closed down Brooks Brothers’ shirt factory. The city is currently being hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2017, U.S attorneys have declared Joe - referred to only by his initials, " J.W." - as the first U.S victim of a global underground drug distribution network. Anthony Gomes will soon be convicted in North Dakota federal court of money laundering and distributing the drugs that have taken the life of Joe Williams and many other Americans.

Authorities arrested Gomes near Fort Lauderdale, Florida in 2017, not far from his $850,000 Tudor Cottage, which according to prosecutors was purchased with drug money. For years, Gomes and his girlfriend, Elizabeth Ton, made bank transfers to China as well as Canada, where their leader operated from his prison cell.

Prosecutors said Gomes, Ton and other members of the drug trafficking and money laundering organisation used offshore accounts, money transfers, Bank of America accounts, and encrypted communication to conceal their operations.

According to information available in an undated spreadsheet from FinCEN files, Gomes and eight other individuals are linked through payments amounting to over $403,000 between 2012 and 2017 through MoneyGram International. The Dallas-based money transfer company paid $125 million in penalties to U.S. authorities in 2018 for violating an agreement to stop money laundering and fraud.

The FinCEN Files spreadsheet, a list of more than 1,500 suspicious activity reports, was titled " VTB Bank Export". This is a reference to a Russian state institution known to be the " piggy bank" of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The U.S. Treasury Department placed sanctions on VTB Bank in 2014 in response to Russia's annexation of the Ukrainian Crimean Peninsula. The nature of the links that VTB Bank had with MoneyGram transfers is still unknown.

VTB Bank stated that it " operates strictly in accordance with local and international laws and regulatory standards. The bank has not received any complaints from US authorities regarding [its] activities " and is " not in a position to comment as it has not had access to the specific documentation referred to in the request”.

Three of the eight people that are named along with Gomes in the spreadsheet have been charged or convicted of drug trafficking. One of them, Xiaobing Yan, is the first Fentanyl manufacturer to be charged in the United States. Yan, 43, operated out of Wuhan, China, and is still wanted by U.S. authorities. He denies that he violated Chinese law or knowingly sold prohibited substances in the United States.

The other two were Ton, Gomes' girlfriend, and Darius Ghahary. Both were charged with Fentanyl-related crimes in 2017. MoneyGram International reported suspicious wire transfers related to Ghahary more than a decade after New Jersey authorities fined him during a high-profile online fraud case.

Who paid who? The roles played by the various players and the exact route that the Fentanyl took to reach Garland both remain unclear. U.S prosecutors in the Gomes case refused to answer ICIJ's questions, citing ongoing litigation.

"Anyone could be a smugler"

Brandon Hubbard, the drug trafficker now incarcerated in a North Dakota prison for selling Joe Williams the drugs that killed him, did not see himself as a financial crook.

" I think of money launderers as people who invest in car washes or restaurants" to legitimise dirty money, Hubbard told ICIJ. " It's what Russian oligarchs do to get their money out of Russia and into American real estate.’’

But then he became one himself. He recalls being shocked when the police informed him that he was accused, not only of distributing deadly drugs, but also of financial crime.

More than 31,000 Americans were victims of synthetic opioids, including Fentanyl, in 2018.

Fentanyl and similar laboratory drugs are about 10,000 times more potent than morphine, killing more Americans than any other opioid to date. The U.S. Treasury Department says financial crime makes this all possible.

" Anyone can be a drug smuggler now thanks to smartphones ", said Donald Im, the special agent deputy in charge of the Drug Enforcement Administration. " If anyone can be an Uber driver, anyone can be a drug smuggler.’’

" Smugglers utilise all the methods of the economy and the financial system", says Im, who works on Operation Denial: an ongoing investigation into the trafficking of Fentanyl and other drugs. The convictions of Brendan Hubbard and Anthony Gomes are the result of this operation.

A few months ago, police called Emily Spell to provide an update. They were having a hard time catching China's " main drug lord ", Emily recalls.

" As small and rural as this town is", she says, " the fact that my brother received drugs from all over the world is really astonishing. "

A day Labourer in Turkmenistan

When it first arrives at the store, the flour smells bad. The oil is black and bitter.

It’s 2016, and Turkmenistan's economy is in free fall. The poorest people are digging through garbage bins. Between 2014 to 2016, inflation reached record levels, second only to Venezuela.

During the day, workers carry bags of cement on their bicycles for a few manats (Turkmenistan’s currency), which is devaluing day by day. In the evening, husbands and fathers spill out past the black plastic doors of empty shelved government supermarkets. All that is left are expensive imported goods.

" There's never enough food", a worker in the southern oasis town of Mary told ICIJ. He asked not to be named for fear of endangering his family. " People wait around for flour until midnight, and the store owners can't say when it will arrive."

The name of the capital, Ashgabat, means ‘ City of Love’. Because of starvation, police repression and corruption, many people now know it by another name: ‘ City of the Dead’.

Corruption in Ashgabat, as in many of the world's capitals, is fueled by the illicit flow of money through offshore outposts - often by some of the world's richest banks.

Nearly three dozen suspicious activity reports examined by ICIJ outline payments linked to Turkmenistan, amounting to $1.4 billion between 2001 and 2016. ‘ Suspicious’ does not necessarily mean illicit, but bank officials monitoring the transfers felt these transactions deserved further scrutiny.

Some UK-based companies received money from Turkmenistan, even though they had reported to supervisors that they were not active in the country, according to ICIJ.

According to leaked information, one case tells of the Turkmen trade ministry sending $1.6 million to a Scottish company called Intergold LP. Bank records indicate that the payment was for ‘ sweets’ - or candy. The money left the ministry's bank account in Ashgabat, passed through Deutsche Bank in New York, and arrived in a Latvian bank account held by Intergold.

Intergold LP was established 10 months before its dealings with the Turkmen government. Its address is a place called Mail Boxes Etc. in Glasgow, Scotland. " Make this place your business address", the storefront suggests.

Intergold has since been renamed SL024852 LP. It is not clear who owns the business or whether it has a legitimate purpose.

James Dickins, who signed the official registration documents when Intergold was founded, has also approved the accounts of at least 200 other companies in England, according to ICIJ’s analysis of the companies included in the FinCEN files. In recent years, British companies have become popular tools for hiding the bonuses of criminals and corrupt officials.

ICIJ was unable to reach Dickins. Daniel O'Donoghue, who also signed Intergold's registration application, told ICIJ that his work is supervised by UK anti-money laundering regulators, and meets the high standards of due diligence and auditing.

" This certainly looks like a case where a shell company has been used to hide funds from state coffers", said Annette Bohr, an analyst at London-based think tank Chatham House, and who specialises in Central Asian kleptocracies. " They probably thought there would be nothing suspicious about depositing 'sweets'."

Turkmenistan's trade ministry did not respond to questions sent via their embassy in the United States, and the ministry's online contact form did not work.

In the documents examined by ICIJ, Deutsche Bank did not explain why it found the transactions suspicious. The bank refused to discuss its relations with Turkmenistan. It told ICIJ that, in general: " discussing possible SARs [...] would be a criminal violation of U.S. (and external) law”. The banks regularly file suspicious transaction reports and " thus help the authorities catch and prosecute those involved in criminal activity ", the bank stated. " Deutsche Bank actively monitors suspicious behavior and shares relevant findings with the authorities."

Deutsche Bank's role in the transactions was that of a correspondent bank - meaning that it allowed Turkmen banks used by ministries and well-connected entrepreneurs to convert manats into dollars, and deposit them into other accounts around the world.

It's a familiar role: the German institution was the international depot of choice for Turkmenistan during the bloodthirsty regime of former president Saparmurat Niyazov.

According to the anti-corruption group Global Witness, Deutsche Bank held up to one-third of the country's income in accounts accessible only by Niyazov. A former president of the country's central bank told the group that Deutsche Bank's billions of dollars were in fact " Niyazov's personal pocket money".

A collapse in Ukraine, a mind boggle on Wall Street

" We were expecting a miracle", says Olga Prykhodko, recalling the day when she prayed in church to see her mother one last time, nine years ago. " But each time they brought out a new person in a black plastic bag, that hope started to fade."

She describes how her mother, Nadezhda Kulinich, looked at her funeral. Her dislocated jaw was wrapped in white bandages. Her fingers were crushed, and her arms were blue - the telling signs of an unsuccessful attempt to protect her face as tons of rock, metal and concrete rained down on her.

On July 29, 2011, Nadezhda Kulinich was one of 11 people killed in a state-owned coal mine in eastern Ukraine, when a tower collapsed on the building where employees were extracting coal from the rocks.

" Mom kept complaining that everything was collapsing", recalls Prykhodko in KyivPost, an ICIJ partner. Nadezhda Kulinich had prior to the accident even told a visiting safety commission that " bricks kept falling on their heads”. Employees complained that the soon-to-be-collapsed tower had not been replaced in 50 years.

Olga Prykhodko blamed " the whole chain of responsibility that goes all the way to the government in Kiev". From the window of her house, she can see the place where her mother died.

Ukrainian miners claim that rampant corruption puts them in danger.

Many of the country's coal mines, including Bazhanov where Nadezhda Kulinich died, are state-owned. According to anti-corruption activists, employees and officials, these mines have long been a favourite source of looting for kleptocrats

Throughout the industry, a lack of adequate equipment was a constant concern. Mine officials said they had just over half of the masks needed to keep miners breathing in the event of a collapse. In an interview with a Ukrainian magazine, the miner’s union complained that old equipment is being taken from unused mines and simply repainted and reassigned.

The collapse of the Bazhanov Tower in the town of Makiivka was one of three mining accidents that took place in Ukraine that week, killing at least 39 men and women. All three accidents occurred in the coal-rich eastern part of the country, near the Russian border, where two rogue " people's republics" operate with support from the Kremlin.

An official commission has identified aging and outdated equipment as a possible factor in the collapse of the Bazhanov Tower and recommended changing the tower inspection procedure.

The Bazhanov mine was supplied by an obscure Cypriot company called Tornatore Holdings Ltd. Months after the funeral of Nadezhda Kulinich, Peggy McGarveym (the main controller of Deutsche Bank on Wall Street) tried to find out who the owner of Tornatore was.

What caught her attention was not the fatal accident, but the warning signs that the had bank picked up on after processing two large payments on behalf of Tornatore.

In December 2011, Tornatore received $5.5 million from a Ukrainian mining equipment subsidiary called LLC Gazenergolizing. The next day, Tornatore sent 999,994 dollars to a large Russian leasing company, partly owned by the Kremlin.

These high value payments wrapped up a year of Deutsche Bank's concerns about Tornatore. Some of these were rounded up to the nearest thousand or million, something experts consider a fraudulent ‘ fingerprint’. The company had made suspicious payments and had no clear domicile or ‘ line of business ’, the bankers noted in reports from March 2011, only a few months before the accident at the Bazhanov mine.

McGarvey and his colleagues saw that the leasing company described the latest transfers as gifts and loan repayments, but the bankers wanted more information according to their report in February 2012. The leasing company's Russian bank, Globex, had in response to previous concerns assured the Deutsche Bank that " the client had not made any suspicious transactions ". But McGarvey's colleagues persisted, asking Globex to provide business information for Tornatore.

" No information", the Russian bank replied. Months later, Peggy still does not know any more than this.

Still head of reporting suspicious activity in the United States for Deutsche Bank, she did not answer questions on this particular topic. It took the involvement of Ukrainian journalists to link Tornatore to the Makiivka accident.

In 2011, Tetiana Chernovol and Yuriy Nikolov reported that Tornatore was linked to Yuriy Ivanyushchenko, a politician who was close to then President Viktor Yanukovych. He was the means of controlling Gazenergolizing, which had a monopoly on the supply of material to the country's mines.

Nikolov, together with Tchornovol (a member of the Ukrainian parliament from 2014-19), wrote that the state mine had purchased replacement equipment from Gazenergolizing before the collapse, but they could not determine whether the equipment had been delivered or whether the order was even legitimate.

But Ukraine's state audit agency released a report in 2011 that paints a bleak picture of the mine's activities. It revealed $21 million worth of damaged equipment at the Bazhanov mine headquarters, miles from the accident. Additionally, they identified $205 million worth of " deficiencies in accounting and gross violations of financial and budgetary discipline”.

Ivanyushchenko fled after the 2014 revolution in Ukraine and is under investigation by Ukrainian and Swiss authorities for allegedly embezzling millions of dollars intended for energy projects. Through his lawyer Vincent Solari, Ivanyushchenko has denied owning or holding any shares in Tornatore or Gazenergolizing. " They allege that the 'information' that's being referred to is false", Solari said.

Joe Williams, Nadezhda Kulinich, Habiba Ghribi and thousands of others fall victim every day to the failure of banks to report suspicious transactions linked to international criminal networks, money laundering and corruption.

FinCEN told BuzzFeed News that it does not wish to comment on " the existence or non-existence of specific SARs". A statement was issued on the unnamed ‘ media’ stating that “ unauthorized disclosure of SAR is a crime that may impact U.S. national security".

A few days before ICIJ and its partners released this investigation, FinCEN Files announced that it was seeking public opinion on ways to improve the U.S. anti-money laundering system.