" We've tried everything to get him back home, but it's impossible for the people who died from COVID-19," he said.

The Tunisian authorities suspended all commercial flights and closed land, air, and maritime borders on March 18. The bodies of Tunisians who died from causes other than the virus have been able to be repatriated to Tunisia by cargo flight, but the same opportunity has not been afforded to the victims of COVID-19. As a result of this decision, many families are distraught over their inability to bury their kin in their country of origin.

an urgent burial

According to the authorities, this decision was made in accordance with strict health rules. " Any repatriation operation requires a certificate of non-contagion. This is a procedure also required by air carriers. It is impossible to issue this certificate for someone who died from COVID-19 and who would be theoretically contagious," says Bouraoui Limam, Director of Information and Communication at the Tunisian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

However, other countries, such as Turkey, have allowed bodies to be repatriated since the beginning of the crisis. A Senegalese collective which has called for the repatriation of Senegalese citizens who died as a result of COVID-19 argues that no World Health Organization (WHO) directive prohibits it.

According to the Ministry, as of May 18, 134 Tunisians had died in France as a result of COVID-19. " Most of the Tunisians who have died here are retired and have been living in France for almost 50 years and were between 60 and 90 years old," Reporters Without Borders declared. "Some were in retirement homes, others had come for treatment," said Naceur Ben Amara, a leading Imam in the Ile-de-France region’s Tunisian community.

Amara described one of the disease’s recent victims, a friend of his, Mr. Aljane, who passed away at the age of 80. After arriving in France in 1962, Aljane worked his way up to open one of France’s first Tunisian pastry shops. When he contracted COVID-19 with his wife, he was unable to be admitted to intensive care because of a reported lack of space. His widow, who is still hospitalized, was unable to be with her husband in his final moments.

In addition to the traumatic circumstances of their loss and the impossibility of repatriating their deceased, many families are unable to honor their family members in accordance with religious burial requirements.

According to the April 1st decree on funeral arrangements, it is forbidden to practice the Islamic ritual of washing and shrouding the dead for health reasons; only prayers can be recited. After receiving a confirmation of death, the medical staff encloses the body directly in a body bag at the hospital in preparation for a mortician to transfer the corpse. " What we want to avoid is keeping the bodies in the mortuary chambers for too long. The most urgent thing is to bury them as quickly as possible," says Imam Ben Amara.

However, it has not been proven that corpses represent a carrier for the virus. Furthermore, the WHO considers that it is possible to respect this practice, affirming that "

the dignity of the dead, their cultural and religious traditions and their families must be respected and protected at all times."

The Tunisian consulate is tasked with supporting the families of the deceased with the remaining burial arrangements. " All we had to do was provide my father's death certificate and papers, they did everything," says Mr. Izakri’s son.

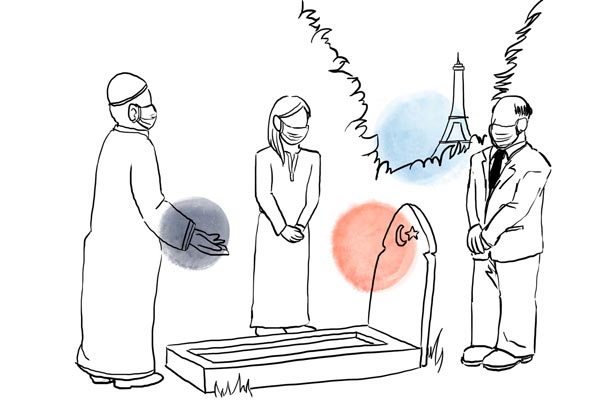

The burial took place in a Muslim section of the Clichy cemetery on the outskirts of Paris, with about 15 people present. " We were able to get close to the coffin, and the funeral attendants helped us. Everything happened as if we had been in Tunisia, maybe even better than if we had been there now," he said, referring to protests following the funerals of COVID-19 victims in Tunisia, during which fears of contamination challenged certain traditions

The lack of muslim plots

Since the beginning of the crisis, Imam Naceur Ben Amara has accompanied about twenty families, whose deceased have all been buried in Muslim plots - a rare occurence in a country with a reported lack of such funeral spaces. " For several years now, we have been campaigning with the Grand Mosque of Paris, the French Council of the Muslim Faith (CFCM), and other religious authorities to have a Muslim plot in every major French commune," says Ben Amara.

To date, only 600 communes out of nearly 35,000 in France have a Muslim burial spaces.

" That's too few. This is all the more so because some mayors have been able to refuse Muslim burials in their communal cemeteries because they don't have Muslim sections," the Imam deplores.

Before the burial, Naceur Ben Amara recites a Dua*, from a distance, in the company of the deceased’s family members. Then, on the day of the funeral, the body is taken by the funeral attendants to the cemetery closest to the deceased's home.

" For the funeral, I advise the chronically-ill, the elderly, and pregnant women not to come," he continues, " only 20 people are allowed to attend. At a funeral in Pantin, 50 people showed up and the Imam had to involve the local council and plead with the family so that only those closest to the deceased could stay. He was a man from Zarzis who had a very supportive environment," he said.

During the ceremony, those present participate in the burrying process. " And at the end they recite a Dua next to the grave. It's efficient and done well. The funeral lasts an hour on average. No one rushes us."

"A break in Family Trajectories"

In Tunisia, many families are greatly distressed about not being able to attend the funeral of their loved one abroad. One of these families are mourning the death of their relative who died in France from the disease. He was a retired diplomat in his sixties, originally from Monastir. " He had joined his daughter and was looking after her grandchildren while she worked in a hospital," said a relative. Already vulnerable due to several chronic illnesses, the grandfather had to be transferred to intensive care shortly after contracting the virus. He died in intensive care, one week after being admitted.

After his death, his body remained in the morgue for four days. Meanwhile, his son based in Switzerland struggled to obtain the documents necessary to attend the funeral. " But for his second daughter and other family members living in Tunisia, not being able to say goodbye to him was heartbreaking," the relative says.

At least 80 percent of immigrants from North Africa are repatriated to their countries of origin if they die abroad, says Valérie Cuzol, a researcher at the Max-Weber Centre in Lyon and a specialist in burial issues for immigrants from the Maghreb and their descendants.

Tunisia has developed a very active repatriation policy, which is almost entirely facilitated by the country’s consular system. The cost of repatriation can cost up to 4,000 euros. Each year, around 500 bodies are brought to Tunisia from France.

While this state mechanism may encourage posthumous returns, it is above all a choice of great personal and symbolic importance. " Post-mortem repatriation is not a simple return to the country of origin," says Valérie Cuzol. " Through repatriation, you reintegrate the deceased into a lineage. There's also a desire to make up for the cost of absence and the break in family trajectories caused by migration," she says.

It should be noted that in the current situation, the Tunisian state will pay for the funeral concessions of COVID-19 victims for only five years, after which the victims’ families will have to bear the cost.

However, in theory, it should be possible to exhume and repatriate the bodies once the situation has calmed down. In Monastir, the family of the deceased diplomat has decided to return his remains to Tunisia. The Izakri family in France has reached the same decision.

" We're going to do everything we can to get my father back, once the situation returns to normal," says the son of the deceased.

But even if this procedure is theologically validated, " it's very likely that many people won't be repatriated," doubts Tarek Toukabri, President of the Association of Tunisians in France. Because although the Tunisian state has assisted in the burials of COVID-19 victims in France, " exhumation and repatriation costs, which are very expensive, will nevertheless be borne by the families," he adds, in a future scenario that none of us can foretell.