Between 2010 and 2015, these two men managed to obtain procedural information, civil registers, birth certificates, death certificates, and marriage and divorce certificates of Tunisians and foreigners residing in Tunisia. They also obtained templates of official documents, family registers, and blank papers stamped with the text “ this copy is in conformity with the original.” All of this was done in collaboration with just a few Tunisian civil servants.

Mikhaïl and Karim created and nurtured personal relationships with each of their targets. Between coffee dates in Bizerte hotels or dinners in La Marsa, the Russian pair learned about administrative procedures, requested confidential documents, and asked about specific people.

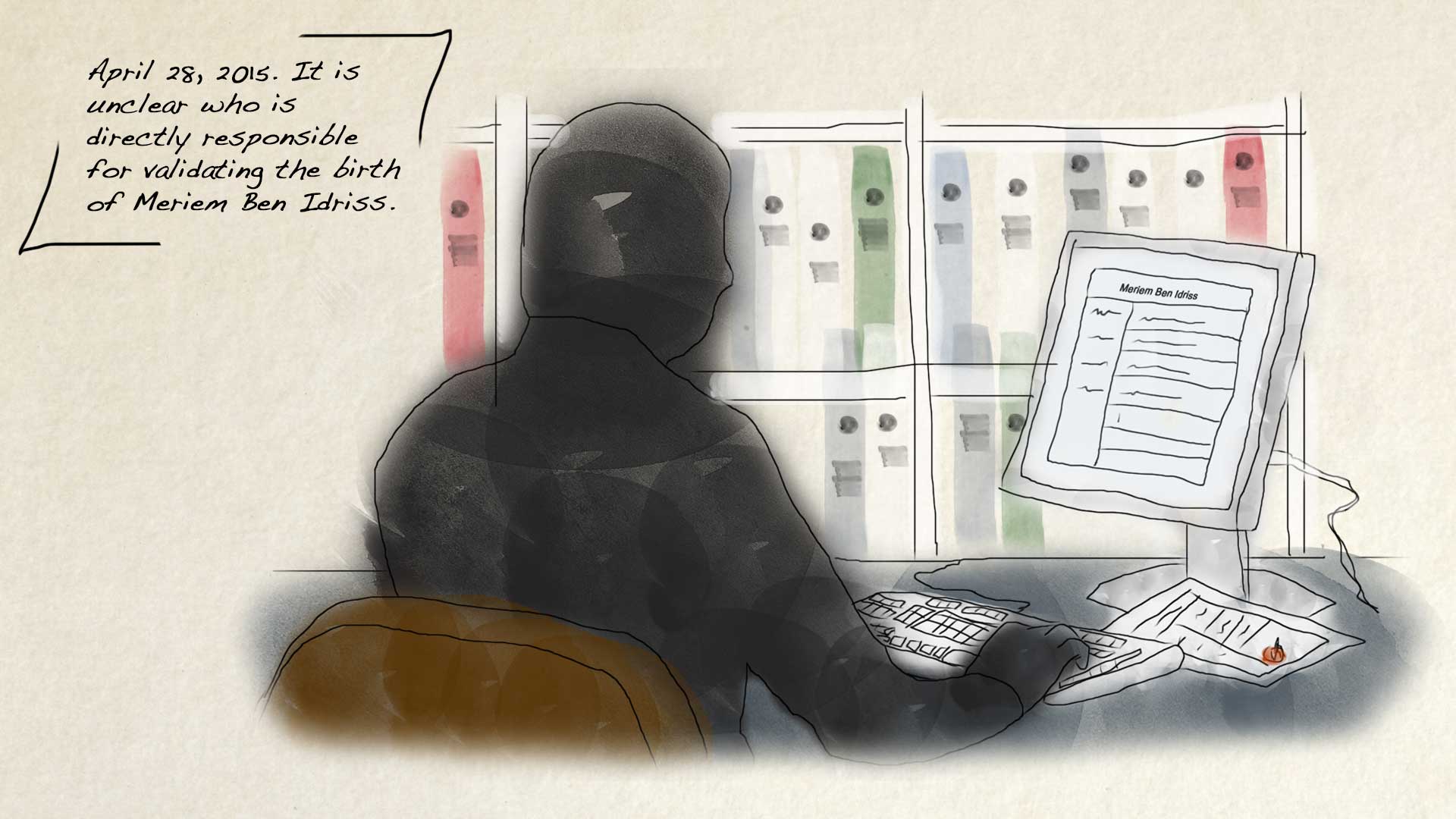

Several weeks before the operation was dismantled, the Russian spies managed to obtain a birth certificate in the name of Meriem Ben Idriss, born in 1986. After a judicial inquiry, it was found that this woman never existed. The fake identity was likely fabricated to provide an identity for an “illegal,” a type of long-term, “deep-cover” Russian spy.

After their arrests, the four Tunisian civil servants testified, revealing the truth behind several years of illegal cooperation. However, the testimonies left some questions unanswered. How did the authorities find out about this spying operation? Why was an employee of the Ministry of Justice called in as a witness and then let free? How did a fake birth in 1986 come to be digitally registered in the central database? Why was a civil servant from the municipality of Bab Souika not brought in to testify, despite being named by one of the accused? Why did some of the accused change their statements between police interrogations and their testimony before the investigating judge?

These are the chronicles of a Russian espionage operation in Tunisia.

Samia, a Bizerte native, had been working for the city for over 20 years. At the time of her arrest in May 2015, she was in charge of the civil registry office. Samia came from a very conservative family and led a constricted life. She went through a traumatic marriage and divorce; her days were spent either in the office or at home. But it all changed when she met Mikhaïl.

At the beginning of 2011, Samia received a call to her office line from a foreigner, speaking in French. Seeing as there are many foreigners in Bizerte, this came as no surprise. The man on the line was Mikhaïl, who introduced himself as the director of a cultural center in Tunis. He wanted to establish a list of Russians registered in Bizerte. So, Samia sent a request to access the birth and death registers to the head of the municipality, who in turn gave the necessary authorization.

After that first call, Mikhaïl comes regularly to consult the requested records. Samia, who oversees these registers, does not notice anything out of the ordinary. After several visits, the two become friends and agree to see each other outside of the office.

Samia and Mikhaïl decide to meet one night in 2011, during the month of Ramadan. He comes to pick her up with his car. She notices that the car has diplomatic licence plates. They go to a hotel café and talk about everyday life and various traditions. On their way back, Mikhaïl hands her a closed envelope and tells her that it contains money. Initially, she tells the investigating judge, she vehemently refuses to take the envelope. But Mikhaïl is relentless, and she eventually accepts it.

When she arrives home, she opens the envelope, and counts 700 dinars neatly tucked inside.

On another occasion, Samia accompanies Mikhaïl to the showing of a Russian documentary in Tunis. On the way back, he gives her another envelope. She resists, he insists, and once again she eventually accepts it. This envelope contains 500 dinars. Several months later, in 2012, they meet again. Knowing that Samia wants to visit France, Mikhaïl gives her 700 euros to help her finance the trip. She travels in December of that same year.

In Samia’s various statements, she never indicates that Mikhaïl asked her to provide him with specific documents; he only consulted civil registers from within the municipality.

In mid-2013, Mikhaïl informs Samia that his term has ended; he will soon return to Russia. But before leaving, he wants to introduce her to his replacement, Karim Brahim, a Russian who speaks Arabic. With Karim, things will change.

Karim and Samia meet in Tunis rather than in Bizerte. For their first meeting, Karim picks up Samia by car. But going forward, Samia agrees to take the bus and meet her “friend” at the Tunis-Carthage airport. Karim meets her there, and they head to lunch. Over lunch, he requests specific documents, and Samia takes notes; she agrees to bring them to their next meeting. Karim proves to be very generous. He gives her 300 dinars for each religious holiday, 400 dinars for some meetings, 1,000 dinars for Omra (a religious pilgrimage to Mecca), a smartphone, and so on.

Samia accepts nearly all of the presents, but draws the line when Karim offers her perfume for her birthday – an act that, to her, straddles the line between friends and lovers.

Samia also proves to be generous, providing her Russian friend with more than just consultations of the civil registers. Starting in March 2014, under the pretext of a comparative study between civil registries in Arab countries, Samia provided Karim with official documents that could have aroused suspicion:

- Templates of birth, death, and marriage certificates

- Prenuptial medical certificates

- Contracts related to the separation of property

- Information regarding criminal record certificates (bulletin n°3), for foreigners and dual nationals

- Original birth and death certificates

Dupont Orion - A stillborn Baby

One of the registers that Karim got a hold of lists births from 1987. The Russian diplomat told Samia that he wanted to find information on Dupont Orion, born on October 11th, 1987 and dead the next day. The register in question was found in Karim’s house during a police search in May 2015. Was he aiming to take dead children’s identities to give to Russian spies?

Russian intelligence used this tactic before, as evidenced by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Operation Ghost Stories. This operation led to the arrest of a dozen Russian “illegals,” or “sleeper agents,” several of whom had appropriated

the identities of deceased children.

Was Samia aware of Karim’s intentions? According to her, absolutely not. But according to her appointment diary, she did in fact know how Karim worked. For example, if he wrote to her about “ emergency situations,” she knew what that meant: it’s time for their pre-arranged meeting scheduled every three months, on a Friday.

She also knew that asking “ How is Hela?” or stating, “ It has been a while since we saw each other” meant that they should meet the next day, in front of a specific restaurant, at a specific time.

Samia was meant to meet Karim on May 15th, 2015 to give him a certified copy of her passport, in French and in Arabic. She never made it to that meeting; she had just been arrested.

Mourad has been working at the municipality of Bab Souika since 2007. After the revolution, he becomes the head of the municipality’s civil registrar. Mourad first met Mikhaïl in June 2010; he had just come to withdraw a document.

September that same year, Mikhaïl comes back, this time to see Mourad. He thanks him for helping him back in June and invites him out to lunch. Three meetings later, Mikhaïl begins to ask Mourad about his work; he is particularly interested in learning about the birth registration process at the municipality. At the end of this meeting, Mikhaïl gives Mourad 150 dinars, plus another 20 dinars for a taxi back home. Mourad accepts. “ Just to help,” Mikhaïl had told him.

In November 2010, Mikhaïl and Mourad meet over coffee in La Goulette. During this meeting, Mikhaïl asks Mourad to get him a SIM card. Mourad agrees, without inquiring why. “ He told me that he did not have time to get one himself,” he explains. Afterwards, the two men begin to meet regularly, about once a month.

Between 2011 and 2012, Mikhaïl is granted an exclusive look into the inner workings of the Bab Souika municipality. He obtains birth certificates of Tunisians born in 1986, learns about administering marriage certificates, and is even told which types of pens are approved for writing into registers. Later, Mourad would admit to receiving 600 dinars in compensation for the information and documents.

In 2013, Mikhaïl insists that Mourad apply for a passport and promises that he can find him work overseas. But Mourad had climbed the ranks of the municipality; he is now the head of a department and is soon to be married. He is not planning to leave the country and is hesitant to follow Mikhaïl’s suggestion, but he eventually acquiesces.

In June 2013, Mikhaïl comes to see Mourad, accompanied by his friend “Karim.” As previously arranged, Mourad hands Mikhaïl his passport. This is the last encounter between Mourad and Mikhaïl. After this encounter, Mikhaïl — and Mourad’s passport — disappear.

A few months later, Mourad receives a message from the phone number that he had acquired for Mikhaïl. The message proposes a meeting in La Marsa. Upon arriving, Mourad is surprised to see that it is not Mikhaïl but Karim, the Russian friend who speaks Arabic, waiting for him. Karim assures Mourad that he will get his passport back.

Karim picks up where Mikhaïl left off; he and Mourad agree to meet each month. Often in La Marsa or in La Goulette, they bounce between subjects; more often than not, Karim steers the conversation towards questions of administrative procedures. In one of these meetings, Mourad agrees to buy another SIM card for his new russian friend, who, like the previous, is too busy to buy it himself.

One day, in January 2015, Karim asks for a list of births registered in 1986, but Mourad refuses. He does, however, take the 150 dinars that Karim offers.

In March 2015, Karim takes another approach. He asks Mourad about a Meriem Ben Idriss, who should appear in Bab Souika’s birth register from 1986. Mourad looks into it and finds that her information is missing from the digital database. So he starts the process to add her.

As it turns out, Meriem Ben Idriss never existed. And Mourad would soon be arrested.

Ihsen had worked for the municipality of La Goulette since 2007 but was transferred to the l’Aouina office, which belongs to the same municipality, following a promotion in 2010. Ihsen never knew Mikhaïl, but in the summer of 2013, he eventually meets Karim, the “ foreigner who speaks Arabic.”

Ihsen first meets Karim in the l’Aouina office; he has come to support his friend who aims to register a birth. Ihsen informs them that they have passed the 10-day deadline to register a birth and that he’s unable to help; they must follow legal procedures. Karim and his friend leave. At this point, Ihsen assumes that Karim comes from an Arab country.

A few months later, Karim and Ihsen meet “by chance” in La Marsa. Two months after that, Karim shows up at the l’Aouina office once again, this time to invite Ihsen for a coffee. At the end of the meeting, Karim offers Ihsen 40 dinars, insisting that he use it for a taxi. Ihsen accepts.

In 2014, Karim takes the next step. With a list of names in hand, Karim requests several birth certificates from Ihsen, who says “ it’s legal” and complies.

Karim returns to the municipality, this time on behalf of a supposed friend of his who has lost his sight. This friend’s birth was registered in the l’Aouina office between 1980 and 1990, but he has no other information to help Ihsen track down his birth certificate. So the two meet for 30 minutes per day over the course of one week to consult the birth registers from those ten years. Later, Ihsen would admit to letting Karim search through the registers in his office, “ in good faith” and always under his supervision. After this exchange, he would never see Karim again.

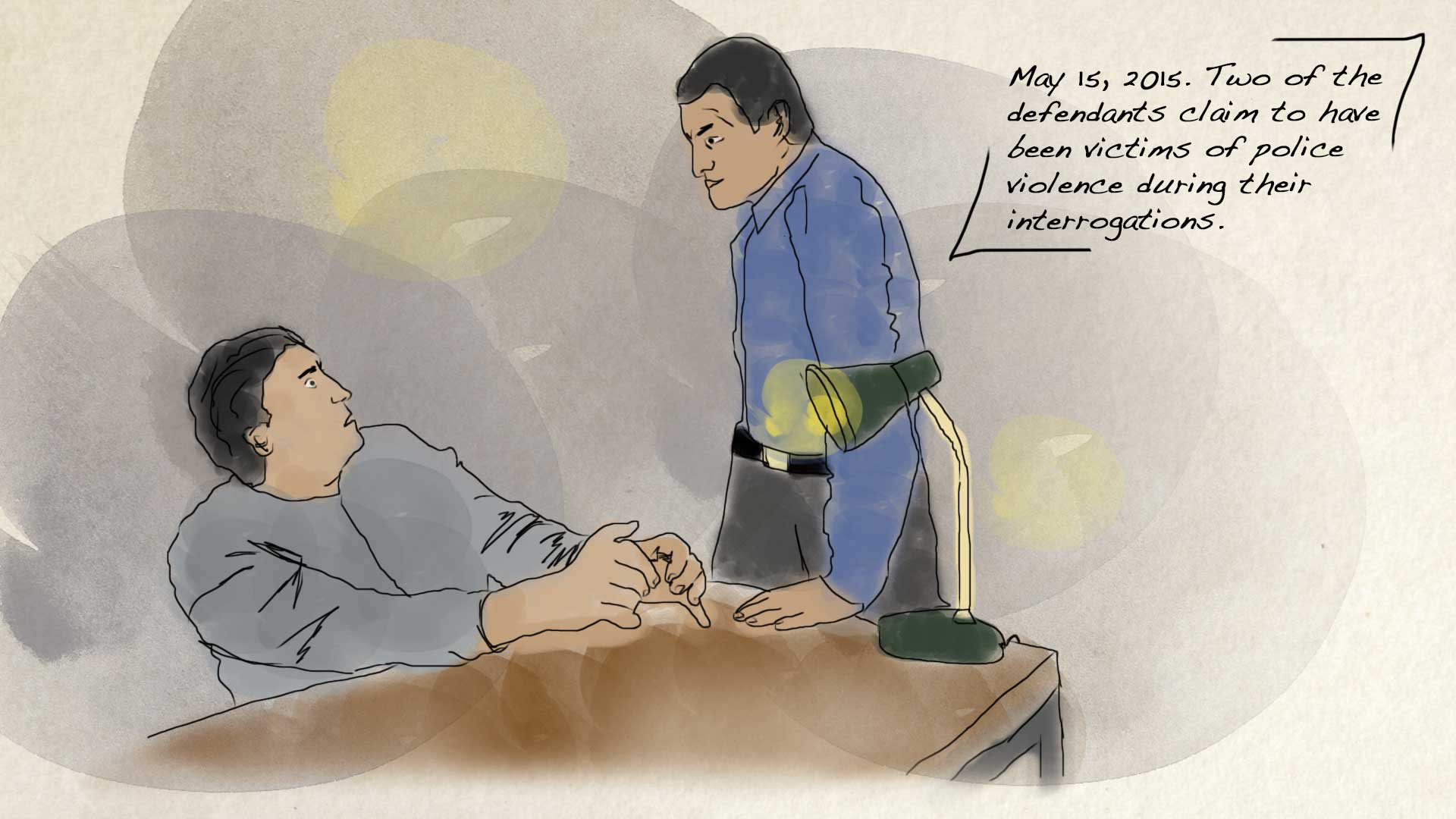

Before the investigating judge, Ihsen stands by a few strong claims: in total, he only accepted 100 dinars from Karim; what was written on the first report prepared by the criminal investigations unit is false; he was beaten and tortured by the police, and the police “ bound him in the position of a grilled chicken;” and, finally, that he signed the hearings’ minutes without having read them.

According to the minutes of the first hearings with the criminal investigations unit, which took place without the presence of his lawyers, Ihsen reportedly gave Karim several registers from the 1980s. He also claimed that two of them were still in Karim’s possession, although none of these registers were found at Karim’s residence.

In addition to being the financial officer — and eventually the head of the civil registry office — for the municipality of El Menzah, Chakib is also the president of the local chapter of a “ summer camp” program. As part of this second job, Chakib organizes an event in May 2013, and while chatting to guests, he encounters a man named Mikhaïl, who addresses him in French.

The next day, Mikhaïl comes back with a friend named Karim. Karim introduces himself as a businessman and says he’s interested in organizing cultural activities. He proposes that he and Chakib launch a Tunisian-Russian collaboration, but a year passes without any follow up.

In May 2014, Karim gets back in touch with Chakib by phone. The two men discuss the idea of a collaboration but fail to schedule another meeting. It’s only in January 2015 that the two men finally sit down over a drink in a hotel.

Chakib inquires about the plans for the collaboration, but Karim is more interested in learning about Chakib’s role at the El Menzah municipality. Karim admits that he is facing a problem: he needs to know how to register a birth after the 10-day registration period has passed. He also asks whether Chakib’s office keeps birth and death records for their region. Coincidentally, Chakib was in the process of consolidating this information in preparation for the municipality’s 50th anniversary, which was created in 1979. He promises to share some information with Karim.

“ The 50th anniversary should have been in 2029!” exclaims the municipality’s president as she testifies during a hearing in July 2015. She claims that she was never aware of any preparations for an anniversary celebration, contrary to Chakib’s testimony.

In April 2015, Chakib and Karim meet for the last time. Chakib gives Karim a blank family register upon the latter’s request. Chakib didn’t see any problem with this request, but he did refuse to mark the document with the stamp that would certify that Karim’s copy conforms with the original.

Chakib gets up to leave for his daughter’s birthday. Karim offers to accompany him, offering chocolate, Italian pasta, and foie gras — all to gift to his daughter. Chakib gladly accepts. They agree to meet on May 18th. But Chakib was arrested three days later. When asked why his meetings with Karim were scheduled in advance, Chakib says that it was just in case they couldn’t reach each other by phone. He had simply wanted to organize a cultural event between Tunisians and Russians.

Mikhaïl Salikov appears for the first time in 2010, in the municipality of Bab Souika, and disappears in the early summer of 2013. He formed close relationships with Samia and Mourad but only met Chakib once, in the presence of Karim. He never met Ihsen.

Mikhaïl was an officially accredited diplomat at the Russia Embassy, but very little information was collected about him. Before disappearing, Mikhaïl introduced Karim to his Tunisian connections. With Samia and Mourad, he paved the way for his successor to obtain the documents they desired.

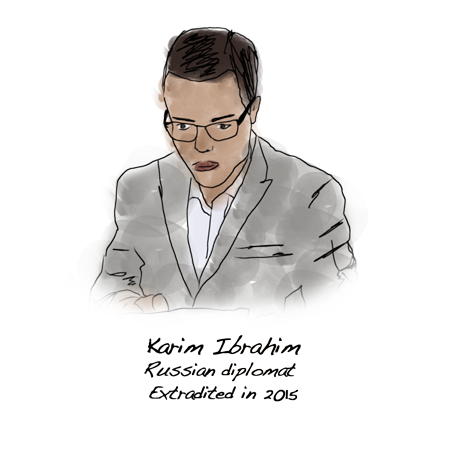

Kyamran Rasim Ogly Ragimov appears in 2013. Unlike Mikhaïl, he speaks Arabic and does not use his real name; he goes by the name of Karim Ibrahim. With Samia and Mourad, he seeks to learn more about two particular identities: Meriem Ben Idriss, a woman registered in Bab Souika but who never existed; and Orion Dupont, a stillborn baby registered in Bizerte.

On May 16th, 2015, Samia and Karim were to meet so that he could return two birth registers to her. Waiting in front of the Bizerte church, briefcase in hand, Karim sees Samia approach, accompanied by policemen. She had been arrested the day before, and the two were escorted to the police station.

During his hearing with the criminal investigations unit in Tunis, Karim accepts the charges laid against him. Did you ask Samia for this document? Yes. Did you give money to Mourad? Yes. Did you have this register in your possession? Yes. But as for the reasons for these acts, he had only one response: “ I refuse to respond to this question.”

Karim informs the police of his diplomatic status; the interrogation doesn’t drag on. Before releasing him, the police escort him home and conduct a search. They find several blank official documents: death certificates, birth certificates, marriage certificates, and documents related to stillbirth. But with diplomatic immunity, Karim gets off easy. He disappears, and the Russian Embassy notifies his landlord that their tenant has left.

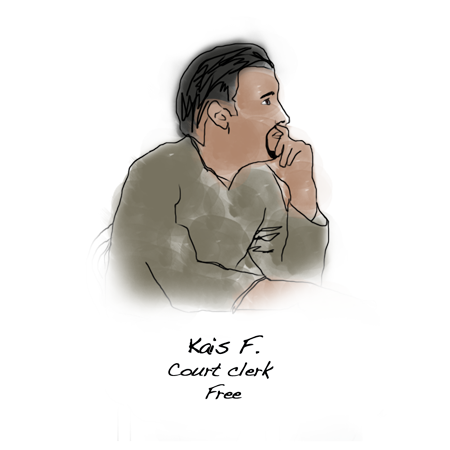

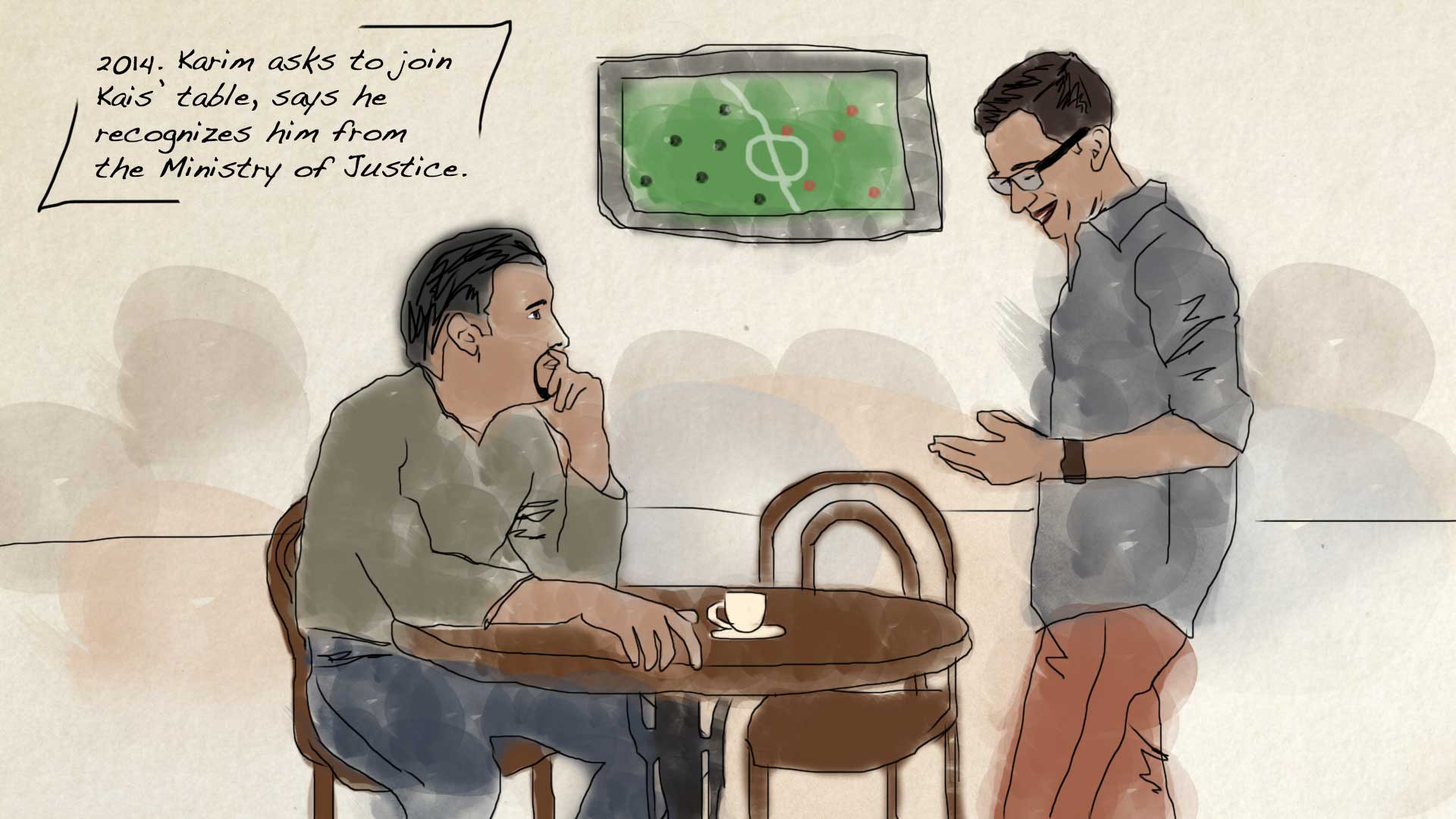

Kais works at the Ministry of Justice as a court clerk. One day in 2014, he settles in a café in La Marsa to watch his favorite football team compete; this is where Karim first introduces himself, as he asks to occupy the seat next to Kais.

As they chat, Karim admits that he recognizes Kais from the Ministry of Justice. He wants to know: how exactly does one obtain Tunisian nationality?

The two men meet again the following week, on a match day. Karim claims that he is Tunisian but lived in Lebanon, explaining his accent. Kais was in a bad mood that day; he had lost his phone.

The next time Karim sees Kais — one month later — he does not come empty-handed. “ In the name of friendship,” Karim gifts Kais a new phone, and Kais returns the favor with a bottle of olive oil.

According to the minutes presented by the criminal investigations unit, Kais and Karim meet for the last time in March 2015. Altogether, they met twice. In another statement, the police indicate that there was nothing suspicious about the meetings and decide to free Kais without any further investigation.

“ How is it that an employee from the Ministry of Justice was cleared of all suspicion so quickly?” asked Imen Bejaoui, the lawyer of one of the defendants. She asks the investigating judge to look into the possibility of complicity between the court clerk and the policemen. Kais does not seem worried.

The case file reveals other inconsistencies. One person was not questioned, despite the fact that her testimony would be key to properly sentencing Mourad, the head of the civil registry office at the Bab Souika municipality. The person in question is Amel, the employee Mourad allegedly called on to enter Meriem Ben Idriss’s birth certificate into the central database. As it turns out, “Meriem” only existed on paper. Her identity had been fabricated by Russian spies and their accomplices.

Hafidha Mdima, head of the municipality of Tunis, clarifies that this action did not follow protocol. A court decision must have approved that a birth certificate from 1986 could be added to the registers decades later. In fact, even accessing the registers required a court decision. Mourad did not take these steps. Employees, also from the Tunis municipality, confirmed another security issue: a strictly confidential password that accesses the central database had been acquired by Mourad and shared with his employees.

“ Administrative sanctions have been taken, the employees are also responsible, and it is strictly forbidden for them to disclose this password,” stated Hafidha Mdima. But no added security measures were implemented following this breach of information.

It appears that the statements of at least two of the accused, Mourad and Ihsen, changed between the versions provided to the police, without the presence of lawyers, and the ones presented to the investigating judge.

Mourad told the judge that he was pressured and threatened throughout his first statement. Ihsen accused the interrogators of torture, saying that they bound and beat him. “ I have no knowledge of complaints on this matter,” responded Sofiane Selliti, spokesperson for the public prosecutor’s office of Tunis.

In the court record, there is no mention of exactly how the spy network was uncovered. The Tunisian authorities have not disclosed further information. From the Russian side, the third secretary at the Russian Embassy “ is not aware” of the case. He arrived after the departure of his colleagues, Mikhaïl and Karim. The secret is well kept.